Not all churchgoers are experts on matters of life and death

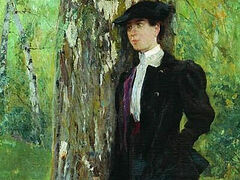

Ivan Vladimirov (1869-1947). Funeral

Ivan Vladimirov (1869-1947). Funeral

For many people, the loss of a loved one becomes a first step towards God. What should we do? Where should we go? In the majority of cases, the answer is clear: to church. But we have to keep in mind that even in a state of shock we should understand why exactly, and to whom (or Whom), you came. First of all, of course, you came to God. But someone who has come to church for the first time may not know where to begin, so it is very important to meet a mentor there who can help to sort through many troubling issues.

By all means, a priest should be that mentor. But he does not always have the time or he often has his day scheduled literally to the minute: services, travel, and much more. For this reason, some priests assign volunteers—catechists, or psychologists—to interact with the newcomers. Sometimes it is done in part by church candle shop workers. But we must understand that we can come across a huge variety of people at church.

It’s as if someone were to go to the doctor’s office and meet a cleaner who asks: “Well, what ails you?” “Something hurts in my back.” “Okay, let me tell you what you should do. Also, here is what you should read about it.”

The same happens at church. It’s sad when someone who is already injured by the loss of a loved one is further traumatized. Frankly speaking, not all priests know how to speak to a grieving person—they aren’t trained psychologists, after all. Likewise, not every psychologist can handle it either because, like any other doctors, they specialize in various areas. For example, I will never, under any circumstances, give any psychiatric advice or work with alcoholics.

Let alone those who offer awkward advice and breed superstitions! It often happens that they aren’t religious people and all they want from the church is to buy some candles, write commemoration notes, and bless the Pascha baskets—yet all their friends turn to them as if they were experts on life and death.

But people who are going through a grieving process require special attention. One should learn how to act responsibly and with great care when dealing with grieving and traumatized people. In my opinion, it should rather be a whole new course of study at Church, no less important than homeless, prison, or any other social ministry.

What one definitely shouldn’t do is infer causal relationships. There should never be anything like, “God took your baby away because of your sins!” How can you know something that only God knows? Words like that can be a deeper blow to a grieving person.

There is no way you can extrapolate your personal experience of death onto others, and this is also a terrible mistake.

Therefore, if you come to church at the moment of severe emotional upheaval, do try to be very selective as to whom you ask complex questions. You shouldn’t assume everyone at church is indebted to you; at my consultations, I often see people insulted by the neglect shown to them at church. Obviously, they forget one important thing—they are not the center of the universe and the people around them aren’t obliged to to fulfill all their wishes.

As for church workers and parishioners, they shouldn’t pretend to be experts when they are being asked for help. If you are genuinely eager to help someone, quietly take his hand, pour a cup of tea and simply lend a sympathetic ear. It’s not words this person needs, but sympathy, empathy, and condolences—in other words, what will help him gradually cope with his tragedy.

What if your mentor has died...

People are often at a loss when they lose their coach or a mentor in life. It could be a mother or a grandmother, or even an outsider, but whose wise advice and sensible mentorship offered protection and stability.

When such a person dies, many feel like their life has come to a grinding halt. How will they live without them? This question seems quite natural in a state of shock. But if the solution has not been found even a few years later, it’s pure egoism: “I needed him, he helped me out; and now that he is dead, I don’t know how go on in life.”

But how about you helping this person now? What if your soul must work hard praying for the deceased while your life becomes gratitude personified for his teachings and wise counsel?

If an adult has lost someone who was very important to him, who shared warmth and sympathy, we should try to keep the memory of it in our hearts and understand that now you, like a supercharged battery, can give this warmth to others. Because the more you share, the more goodness you bring into this world, the greater praise that reposed person deserves.

If you were a receptacle of someone’s wisdom and warmth, how can you cry that there’s no one who can do it anymore? Share it with others, and you’ll receive that once-lost warmth, but from other people. And don’t be too self-obsessed all the time, since egoism is a grieving person’s greatest enemy.

What if the deceased was an atheist?

In fact, everyone believes in something. And if you believe in eternal life, then you should understand that a man who claimed to be an atheist is on the same page with you now, after death. Unfortunately he found it out too late, and your job is to help him with intercessory prayers.

If you knew this person well, then to some degree you are an extension of him. And much depends on you now.

Children and grief

Konstantine Makovsky. A child’s burial in the country. 1872

Konstantine Makovsky. A child’s burial in the country. 1872

This is a separate vast and very important topic, and I have an article written about it called “Age specifics in the experience of grief.” Until he reaches the age of three, a child has no understanding whatsoever of what death is about. It happens only around the age of ten when a child begins to form a perception of death similar to that of an adult. We should always take this aspect into account. In fact, Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh spoke at great length about it (I consider him a profound expert on crisis psychology and spiritual counseling).

A lot of parents worry whether the children should be present at the funeral. As you look at the painting, “A Child’s Funeral” by Konstantin Makovsky, you can’t but wonder: So many children! Good Lord, why are they there, why are they looking at it? But why wouldn’t they stand there if their parents had taught them that we shouldn’t be afraid of death, because it’s a part of our life? In the old days no one screamed at the children, “Oh no, go away, don’t look!” After all, the child will come to realize that if he was so ignored, something really awful must have happened. In such a situation, even the death of a little pet turtle could cause mental illness.

Besides, children had nowhere else to go to back then; if someone died in the village, everyone went to say goodbye to him. It is natural for children to attend a church funeral service, where they mourn and learn to react to death, or do something good in memory of the deceased, such as praying or helping at funeral repast. Parents often traumatize their children in an attempt to shelter them from negative emotions. Some even turn to deceit: “Daddy went on a business trip.” As a result, the child eventually gets resentful—first with his father for not returning, and then with his mother because he feels that she kept something back. But when the truth comes out... I have seen families where a child simply couldn’t interact with the mother because of her deception.

I was stunned by the following story: A girl’s father died, and her teacher, an experienced professional and also an Orthodox believer, told the classmates to avoid bothering her since she was tormented enough. But in fact it traumatized the child once again! It is horrible when even those who have teaching degrees and believe in God have no idea what child psychology is about.

Children are no worse than adults and their inner world is every bit as deep. By all means, when we talk to them, we must factor in the age aspect of the perception of death—but we shouldn’t keep them away from sorrows, difficulties, and trials. We must prepare them for life in the real world. Otherwise, they will become adults but they will never learn to deal with losses.

What it means to “survive the sorrow”

To fully survive grief is to transform dark sorrow into a bright memory. A surgical suture is what remains after surgery. When it is properly and neatly sutured, it neither hurts nor bothers you, nor feels tense any longer. It is the same with grief— we will still be scarred, plus we will always remember our loss. Yet we will not endure it in pain, but instead feel grateful to God and to the deceased person for his presence in our life. And we will nurture the hope of a future meeting in the age to come.