The Sorrowful days of Great Lent.

The slow and weeping chime of bells after the excitement of Maslenitsa (the Cheesefare Week) sounds like a call from Heaven, the voice of conscience going into the heart... Clergy are in mourning vestments, and the choir sounds as if it is weeping. The soul, conscious of its crimes, melancholy because of its falls, has thrown itself at Christ’s feet and is groaning...

“Where shall I begin to lament the deeds of my wretched life? What first-fruits shall I offer, O Christ, for my present lamentation?” (Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete; Monday:1.1). And in response to this cry of the heart the clergy answer with compunction: “Have mercy on me, O God, have mercy on me.”

At the evening service the news of the approaching Bridegroom, Who is to visit the soul awaiting Him, is spread: “Behold, the Bridegroom comes at midnight, and blessed is the servant whom He shall find watching...” And at the end of these days of repentance there is the quiet Supper of Christ, with these words sounding again and again: “Take, eat; this is My Body”; “Drink ye all of it; For this is My Blood.” And there is the sign over the world—Christ pierced on the Cross, and His Blood pouring from His wounds with its composition enters the bodies of the faithful—a miraculous deification.

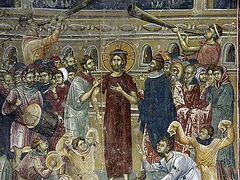

A Christian—repentant, cleansed and united with Christ—after the labors of fasting, after the joy of the resurrection of Lazarus and the triumph of the Entry into Jerusalem, remembers the last days of the Savior’s earthly life.

Before the Liturgies of Holy Week the Church briefly retells people the whole story of Christ’s earthly life, and the Gospels of all the evangelists are read. We recall the meal at which a zealous woman prepared Christ’s Body for burial, coming with an alabaster box of very precious ointment (something that humanity will never forget); the fateful bargain for thirty pieces of silver; the Last Supper...

What a joy it is for the soul to take Communion on the anniversary of the unforgettable day when the Holy Eucharist was established! Through the space of so many centuries you feel invited to this supper, instituted for centuries and millennia by the greatest sacrifice of Christ's love!

And now the reading of the twelve Gospels on the Lord’s Passion is heard in the midst of the candles shedding tears. Here Christ’s final, mysterious talks are collected, and all the suffering of the God-Man, to Whom the soul is listening “ashamed and marveling”,1 is contained within a short space. And in memory of this hour, when our heart merged with the suffering heart of the Godhead, people bring burning candles, which they will then keep and light at the hour of the separation of the soul from the body.2

Then the taking out of the shroud with the remembrance of “noble Joseph” and the vigil at Christ’s tomb follow. And after the Liturgy of Holy Saturday, when the angels’ arrival at the tomb is announced and black vestments are changed for white ones, the evening of Holy Saturday comes, full of hidden expectation.

How good these hours are in ancient cities with sacred Kremlins and numerous churches, among which the great Reposed One silently rests in a mysterious dream!

O, before Him let… “all mortal flesh keep silence and with fear and trembling stand; ponder nothing earthly-minded”... Platforms are set up in many places around churches, along which joyful Paschal processions will stretch. The streets are deserted, and life hides waiting behind the walls of houses.

Lights have been lit in the night around churches, and people have walked to meet the Risen Christ. At midnight the bells rang, and with the banners of the victory of Christ unfurled, processions move and return to churches while singing words that we would repeat endlessly, without end, in which all the promises and all the grace of Christ’s deeds are contained: “Christ is Risen from the dead.”

At the end of the Paschal Matins, heartfelt words are sung: “Having slept in the flesh, as a mortal, O King and Lord, on the third day Thou didst rise again, raising up Adam from corruption, and abolishing death: O Pascha of incorruption, salvation of the world!”

These last words rise in a kind of spiral into the dome and fall from there onto people. They speak about one of the mysteries of Christ’s life—about the change of His flesh. For forty days after the Resurrection, before His Ascension to Heaven, the Lord was in a special state of flesh, when He passed through closed doors, but at the same time He ate with His disciples and allowed the Apostle Thomas to touch His wounds.

A nineteenth-century pilgrim in Voronezh, standing at the altar during Matins presided over by the great ascetic, Archbishop Anthony,3 saw that while singing the words, “Having slept in the flesh,” the hierarch changed completely, as if his flesh had disappeared, thinned, and he became all transparent... It is a pity that The Paschal processions held throughout Bright Week do not take on such a scale with us here as they could and should take. They would make a colossal impression on believers and non-believers alike if all the city clergy would go marching together along the main city streets with the banners of all city churches and the general singing of all church choirs and people. What a triumph of Christ's victory! And then comes the Ascension, in which our joy for Christ, ascended into the Father's glory after His humiliation on earth, is mixed with secret sadness that He was separated from the earth after thirty-three years on it.

But after all, we are left with His Gospel, the life-giving stream of His Blood, which did not flow over the earth in the days when He walked on it preaching the Gospel. And His wonderful promise is left with us: I will not leave you comfortless: I will come to you (Jn. 14:18).

From the book, Ideals of Christian Life