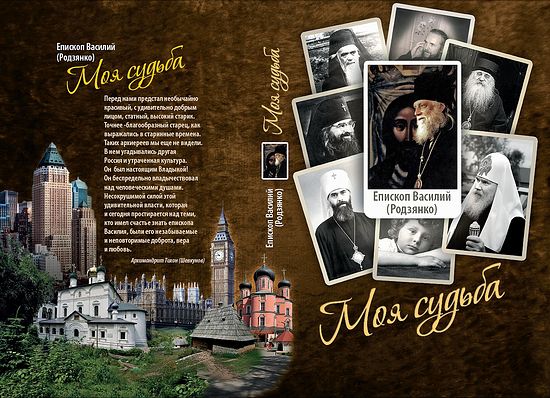

The Sretensky Мonastery publishing house published a book of memoirs by Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) called “My Fate” and compiled video transcriptions from 1997–1999. The majority of them is being published for the first time.

Vladyka Basil speaks about his family, childhood, and the tragic events of the last century in Russia and the fates of the people deprived of their Motherland. From the Vladyka’s memoirs, one can study the history of the Russian Orthodox Church in the twentieth century and the history of the Russian Church Abroad. Bishop Basil met with practically every well-known hierarch of the time, the devout servants of God and the leaders of the Church. One of the chapters of the book is devoted to the memories of Fr. Nicholas (Gibbes) who converted to Orthodoxy and was tonsured a monk with the name of Nicholas, in memory of His Majesty the Emperor.

I learned from Fr. Nicholas (Gibbes) about the “secrets” of the Imperial children’s room and his attitude toward this family.

He became a tutor to His Majesty’s children purely by accident. Someone recommended him, they liked him, and his candidacy was approved. He unintentionally became a member of their family.

He was so attracted to Orthodoxy, which he learned about while tutoring the children of the Emperor and the Empress, that after the revolution, when the Imperial family had to travel to Tobolsk deep in Siberia, he went there with them and shared the hardships that befell the family. Later on, he followed them to Ekaterinburg. But, since those who transported the family knew the fate that awaited them, as a foreign citizen he was separated from them. He lived to see the tragic day made known to the world and took it very hard. All of this led him to become a monk. Together with the Kolchak army retreating by way of Siberia, he ended up in Harbin, a quintessential Russian town in Manchuria. This was because of its location on the Chinese Eastern Railway, which employed many Russian nationals, which helped to Russianize the town even before the revolution. It was where he met Vladyka Nestor (Anisimov), a missionary to Kamchatka, and later to China. Vladyka Nestor founded the Russian Orthodox House of Mercy in Harbin. That’s where Sidney Gibbes was received into the Orthodox Church and tonsured a monk, adopting the name Nicholas in memory of His Majesty the Emperor Nicholas II. He served there as a priest right up to the beginning of the Second World War. For a number of reasons, he had to return to his homeland, and was back in London in 1938. He served in a Russian Orthodox church there conducting services in English, for the English speakers. He was later assigned to an Anglican Church building right in the middle of London.

I became closely acquainted with Fr. Nicholas and learned from him a lot of details unknown to others. He told me what happened after he had found out about the tragic death of the Imperial family. No one knew how they died or were the bodies of the slain where buried. This only became known after the investigator Sokolov arrived to Ekaterinburg. Colonel Pavel Pavlovich Rodzianko, my uncle and my father’s cousin, also arrived there with the Kolchak army. He, along with Sokolov and Sidney Gibbes (the future Fr. Nicholas) who joined them, launched an investigation. They descended into the mine that they assumed was the burial place of the members of the Imperial family. They inspected Ganina Yama, but found nothing but a few things. That’s where, Fr. Nicholas told me, he found nails, the large ones, at the bottom of the mine. He immediately identified these nails. They were kept in the heir’s pocket. When he, the tutor, and his charge would play a game of skittles or something like that, they’d usually set these nails out and then throw a ball. Once he discovered these nails, it became clear to him that the boy was killed and his body lay here. They collected the nails and other items they had found in a special suitcase. Pieces of burnt bones were already stored inside it. They also discovered the traces of two large fires and obvious attempts to burn the human remains. As we know, the investigator Sokolov held that all bodies were burned there, but they had no sufficient evidence to prove it. Fr. Nicholas never learned about the final results of the investigation.

It should be mentioned that my uncle discovered there not only the remnants of death, but also of life. He found the heir’s beloved dog named Joy. It was running around next to that area where the human bodies were burned, or at least attempted to be burned. However, nothing else was found there.

Basil (Rodzianko), the Bishop. My Fate. Memoirs / Comp. D.V. Glivinsky. – M: Sretensky monastery, 2015, 416 pp.

Basil (Rodzianko), the Bishop. My Fate. Memoirs / Comp. D.V. Glivinsky. – M: Sretensky monastery, 2015, 416 pp.

Everything that was found there was moved away—yet another interesting connection with my family—with the help of the grandmother and grandfather of Peter Sarandinaki, a Russified Greek and my niece’s husband. Peter Sarandinaki knew everything in great detail about his grandparents’ life. His grandfather was a general in the Kolchak’s army. He was assigned to bring this makeshift shrine in a suitcase to Europe. They took it to Western Europe in a roundabout way, via China and other countries. Afterwards, this suitcase was hidden in the wall of a memorial chapel to Emperor Nicholas II in Brussels, on the commemoration day of Righteous Job the Long-suffering. The Emperor was born on that feast day, so he often spoke and wrote about it in his diary that, since this holy sufferer has been his patron saint, he will also bear a lot of sufferings.

Joy was taken to Buckingham Palace. My uncle arrived there upon the invitation of King George V who, as is well known, was the Emperor’s cousin and looked like him so much that people always confused him with his cousin, especially in youth. King George V and my uncle Pavel met privately; not even a valet was present. That’s where my uncle shared everything he knew about the death of the Imperial family and the dreadful discovery. Joy, handed over to the king, somehow assuaged his sorrow. This little dog brought joy to the Windsor Castle and was buried, when his time has come, in Windsor Park. Even in our days, one can find its soul-stirring gravesite—a symbol that all nature, including all creatures great and small, is united in the Kingdom of Heaven. The king did have the slightest chance to provide help to his close relatives. We should also keep in mind that Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was a favorite granddaughter of Queen Victoria; she loved this country (England) dearly and was loved in return.

The question arises: why didn’t the Royal Family assist in taking the Imperial family to safety? They say that it was impossible for political reasons—the liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George was against it. They feared that it might negatively affect international relations between the two countries. It is possible, we don’t know. But my uncle used to say that the king took the death of the Imperial family as a personal tragedy. Besides, even to this day, the Royal family still remembers it with overwhelming sadness—and we are aware of it.

Fr. Nicholas shared a lot of stories about the remarkable Imperial family he loved so dearly. He has provided insight into their life—the mutual love and deep faith that ruled this family, and how they were treated by their British relatives. Therefore, I do not judge anyone.