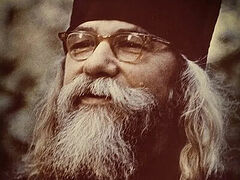

We present to the readers of OrthoChristian memories of the remarkable Russian writer Nina Pavlova (now reposed, unfortunately) dedicated to Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) and Optina Monastery. In the Orthodox world, Nina is known first of all as the author of the book Pascha of Beauty (Pascha Krasnaya), dedicated to the three murdered Optina monks. But not many know that she ended up in Optina precisely with the blessing of Fr. John, who greatly contributed to her spiritual maturation, especially as she was taking her first steps into Church life.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) I can’t even believe it myself now: Was there really a time when you could just sit “at the feet” of Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), spending a long time listening to the Elder’s Divinely-wise words? True, it didn’t happen often—the Elder was “protected” from visitors in every possible way. It usually went like this: Batiushka comes out of the church, and the many pilgrims who came to the monastery for his counsel rush over to him.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) I can’t even believe it myself now: Was there really a time when you could just sit “at the feet” of Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), spending a long time listening to the Elder’s Divinely-wise words? True, it didn’t happen often—the Elder was “protected” from visitors in every possible way. It usually went like this: Batiushka comes out of the church, and the many pilgrims who came to the monastery for his counsel rush over to him.

“Batiushka,” a woman shouts through the crowd, “my son went missing a month ago. Is he alive, or has he been killed?”

The Elder turns to the crying woman, but they don’t manage to talk. Some people (perhaps security?) push the woman away from the Elder, and they lead him very quickly through the crowd, taking him by the hand, professionally. But the woman doesn’t give up, but runs after the Elder shouting, choking from her tears:

“Batiushka, dear! My only son! O Mother of God, save and help us!”

And then Batiushka somehow wrests his way out of the guards’ hands and blesses the woman, comforting her:

“Your son is alive and will be back soon.”

That’s how people spoke with the Elder—on the move, on the run, more often in writing, passing their questions through his cell attendant Tatiana Sergeevna, and receiving an answer through her as well. And this woman’s son came home the next morning.

But still, there were holidays on our street when Batiushka John would talk with people for a long time in depth. That’s why I vividly remember the spring of 1988 in the Pskov Caves Monastery. It was warm, the sky was blue, and the maples glistened with such a golden glow, like halos above the churches. The monastery leadership was summoned to Moscow, and Archimandrite John would say, coming out of church:

“Well, the authorities have left us. There’s only us, some charred firebrands left.”

As always, Batiushka is surrounded by people, and the short path to his cell turns into a two-hour conversation. Someone brings him a chair and we sit at his feet on the grass. And questions follow questions:

“Batiushka, what is perestroika?”

“Perestroika? A skirmish, a shootout.”1

“Batiushka, bless my mother and me to move to Estonia. We found a good exchange in Tapu.

“What do you mean to Estonia? What, you want to live abroad?”

I listen and wonder: How is Estonia abroad? And perestroika—it’s… It’s a time of rallies, enthusiasm, and intoxication from freedom. But how bitter the hangover was when the great power became impoverished and collapsed. Estonia became a foreign country. And much blood was soon shed at various flashpoints and at the White House.2

Holy Dormition-Pskov Caves Monastery

Holy Dormition-Pskov Caves Monastery

But for now, the sky is blue overhead, and a shy girl with blush on her check asks Batiushka how to milk cows. Some frown, not even hiding their mockery: You’re talking with an archimandrite about something so trifling? But for a young girl it’s not so unimportant—she has the monastery obedience of milkmaid, and the cows sometimes kick and don’t allow her to milk them. Out of embarrassment, the girl speaks in a whisper, but Batiushka’s answer is heard by all:

“There was an instance in my childhood. One cow used to give a lot of milk, but then it suddenly started returning from the pasture empty. We started following the cow and we found that at the watering place by the river, it always wandered into the creek where we knew there were catfish. The catfish would swim up to it and drink its milk. Catfish have soft, tender lips, and the cow liked the caress. Do you understand now how to milk?”

“Like a catfish,” the girl said smiling.

“Like a catfish.”

***

People would ask the Elder various questions, but the main question was: How should we live?

“Batiushka, I was baptized recently, and now I want to quit my job to live near a monastery and pray to God,” says one pilgrim from Norilsk—a music teacher, about fifty years old.

“So you want to become unemployed?” the Elder clarifies. “And how will we pay for electricity?”

“What do you mean for electricity?” the woman asks and stops short, realizing that even in a village you need money to pay the electric bill and buy bread. “Batiushka, tell me how I should live.”

“You need to work until pension time. Our pension gives us wings.”

“Batiushka,” the pilgrim continues to ask, “can Orthodox people take medicine?”

“Why not? Doctors are from God.”

I know this pilgrim. We were both recently baptized in the monastery. We met there, having come under the care of some austere pilgrims in black who predicted the imminent coming of the antichrist and felt his presence everywhere in the world. My new friend and I didn’t understand it yet, and the “zealous” pilgrims enlightened us: Tea and coffee are demonic drinks. High heels are also demonic, because a high heel is actually a hoof, and it’s obvious whose. And about the fact that they sell demonic chemicals in pharmacies, and that art is the fetid miasma of the netherworld—well, there’s nothing to say. The “zealots” also convinced us that you have to dress piously, and soon a music teacher appeared in the church, dressed like them: a black head covered in a “frown,” tied all the way down at the eyebrows, a crooked cotton skirt to the heels and large, coarse men’s shoes. It was a bit uncomfortable to see this masquerade. However, a week later, the “zealots” had already dressed me up all in black.

Tatiana Sergeevna Smirnova And then there was this scene: I was walking through the monastery courtyard in this masquerade as a black crow, fancying myself quite pious, and Fr. John looks out the window of his cell at my piety and knocks on the glass, trying to say something. Batiushka’s cell was on the second floor. The windows were already sealed for the winter and I had no idea what he was saying.

Tatiana Sergeevna Smirnova And then there was this scene: I was walking through the monastery courtyard in this masquerade as a black crow, fancying myself quite pious, and Fr. John looks out the window of his cell at my piety and knocks on the glass, trying to say something. Batiushka’s cell was on the second floor. The windows were already sealed for the winter and I had no idea what he was saying.

“Batiushka, I can’t hear you!” I say from below.

And then Archimandrite John sends me his clerk Tatiana Sergeevna to tell me that Batiushka is asking me not to dress in black.

I change into my usual clothes, and the “zealots” begin to despise me so much since then that I miss out on valuable information about the demonic properties of tea and art. In general, I drink tea, read Tyutchev, and I love good paintings and the marvelous beauty of Pavlovo Posad shawls. The shawls are also from that fall—the designers, a husband and wife, came to the Elder for advice. Both are landscape painters and participate in exhibitions, and to earn money (they have many children), they design shawls at the factory. The wife takes them out of her bag and shows them, somewhat shyly. And the shawls are a wonder, a celebration of joy in color! But the husband seems to look at this factory day work differently. He told us a little later about how he was shamed by some “zealot,” saying he should be painting churches, not grandmas’ rags. In a word, the artists humbly ask Batiushka to bless them to give up secular art so they can paint icons exclusively. I remember the Elder’s answer:

“There are enough iconographers without you, but the world gets sick without beauty.”

Batiushka also spoke to us about those “self-made crosses,” when a man rejects the path to salvation given him by the Lord—when he doesn’t want to bear the cross of providing for a large family or caring for his sick parents, but invents a special “spiritual” life for himself in haughty wisdom. We exchange glances—it’s about us. Every one of us has his day job, his own sorrows and those hardships in life that we’d love to escape by going to a monastery or leaving our family in a heated moment. How many families already on the verge of breaking up were saved then thanks to the Elder!

But I should talk about these families separately. For now, I’ll talk about the main lesson I got from the Elder: Don’t descend from the cross—you can only be taken down from the cross, but to run from your cross is to run from Christ.

Nina Pavlova But how difficult it is sometimes to carry this cross given by the Lord! I remember complaining to Batiushka then about my sorrows, and I soon received a written response from him:

Nina Pavlova But how difficult it is sometimes to carry this cross given by the Lord! I remember complaining to Batiushka then about my sorrows, and I soon received a written response from him:

My dear sorrowful Nina! I call you to a spiritual deed—to go further after Christ, to walk on the waters, overcoming the sorrowful circumstances of your life by faith alone. Suffering has already taught you much, revealed many of the intimate secrets of the spiritual life; and how many of them still lie ahead, but they come at the price of suffering.

And to you, dear Nina, I speak not from myself, but from the Holy Fathers:

“What can bring calm in the fierce times of spiritual distress, when any human help is either powerless or impossible? The only thing that calms is the awareness of yourself as a slave and creation of God; only this awareness has such power that as soon as a man prays to God from his whole heart: ‘May Thy will be done in me, my Lord,’ the agitation of his heart subsides from these words, uttered sincerely, and the heaviest of sorrows lose their dominance over a man.”3

This is for you on those days when the mist covers the sky above your head and the Lord has seemingly left His creation.

God’s blessing to you and O.

“The flesh prescribes one thing to me, and the commandments another.

One is God, the other an envier.

One is time, the other—eternity.

I shed hot tears, but they haven’t wiped away my sin.”4

And now let us weep and be saved. May the Lord keep you, which we will pray for.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin)

How the letters and prayers of Archimandrite John supported me in those difficult years! Batiushka is a bright light, a comforter, with a martyr’s fate. He returned from the camps with broken fingers on his left hand, but he avoided talking about his years of imprisonment, thwarting all talk about it. But still, one day, unable to resist, I asked:

“Batiushka, was it scary in the camps?”

“For some reason, I don’t remember anything bad,” he said. “I only remember: The sky is open and the angels are singing in the heavens.”

This was the main thing I experienced when I met with the Elder—the feeling of an invisible grace-filled light pouring down on us from Heaven, and how it’s easy to be with God in sorrows.