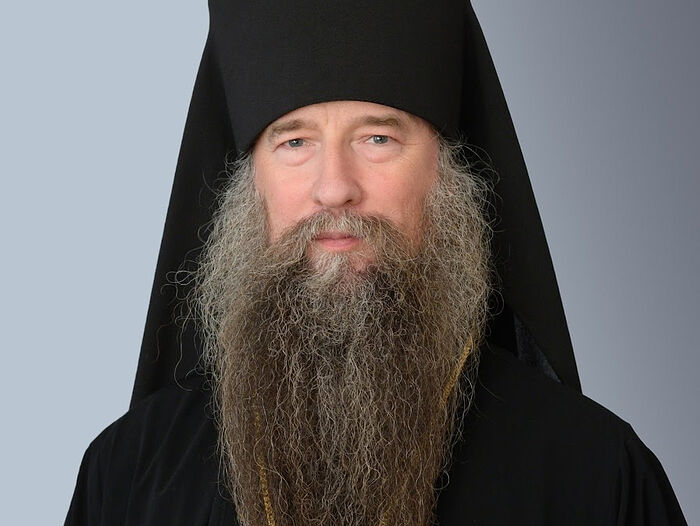

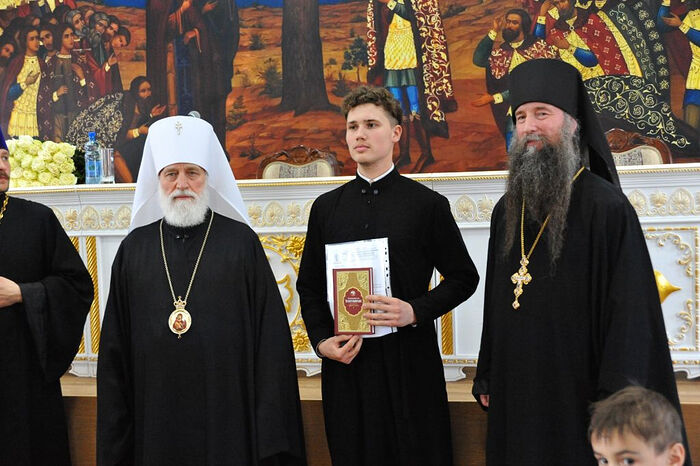

Bishop Kirill of Zvenigorod, Vicar of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, rector of the Moscow Theological Academy, a member of the Synodal Commission for the Canonization of Saints, Doctoral Candidate of the Institute of Postgraduate Studies, a Ph.D in Engineering… There are many obediences and duties in His Eminence’s life, but, as he says, the most important thing is to always remain faithful to God and not to abandon prayer. For this almost a quarter of a century ago he chose the monastic path. Bishop Kirill has talked about what it means to be a monastic in the twenty-first century, why you can be a scholarly monk as an obedience, and how to determine whether a seminarian will grow to be a true pastor.

—Vladyka, let’s first give a definition of monastic life.

—The Church understands monasticism first of all as the preservation of the spirit of the first Christians, who were true disciples of Christ and ready to follow the Lord to any place, to any service. It is an imitation of apostolic zeal, which after the descent of the Holy Spirit was strengthened in a special way. As the Apostle Andrew the First-Called said, “If I were afraid of the Cross, I would not preach it.”

And this is an imitation not only of the apostles, but also of Christ the Savior Himself and the Mother of God, Who set an example of such a life which is entirely devoted to serving the work of God without dividing people into friend and foreign, and the perception of all mankind as Adam’s one race. Monasticism is the spirit of reasonable zeal for the glory of God, combined with the desire to serve God and people.

Although, of course, this spirit manifests itself in different ways, including in the eremitical life, when this service to people seems invisible. But nevertheless, as Elder Silouan of Mt. Athos said, through such ascetics the whole world still stands. Perhaps there are only a handful of them—people whose prayers are so strong that they preserve the well-being of the whole world.

—One of the main patrons of our Sretensky Monastery is Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky). He loved the Moscow Theological Academy, was the youngest professor of his time, and even served at the Academy inspector.

—And for half a year he was the acting rector (smiles).

—Sretensky Academy is actually part of Sretensky Monastery, but the Moscow Theological Academy, like St. Petersburg Theological Academy, where you and your brother Fr. Mefody were tonsured, are somewhat separated from the monasteries they are associated with. So there are some differences between Lavra monks and scholarly monks. In your opinion, what is special about academic monasticism?

—A learned monk devotes much more time to studying book wisdom. And although it can be safely said that monasteries have always been centers of education, where manuscripts were copied and libraries were collected. Nevertheless, with the advent of theological schools, many teachers and administration have had to completely devote themselves to God, to learning as such, and to the educational process.

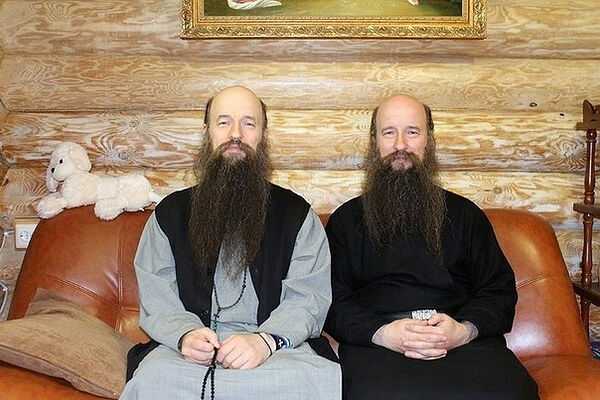

Brothers Mefody and Kirill (Zinkovsky)

Brothers Mefody and Kirill (Zinkovsky)

There is a tendency among monastics to consider that learned monks do not quite correspond to the ideal of monasticism—they have too much scholarship. But in fact, I always emphasize that a monastic should be open to any obedience; he can do both physical and academic work. If he devotes all this to the Lord and His Holy Church, to some extent what exactly he does becomes secondary.

The monastic is called to live in passionlessness, which is attained through the skill of cutting off his will. On attaining with God’s help even the initial stages of dispassion he becomes joyful in any work, whatever it may be: monotonous physical labor or academic work, which is also often monotonous. That is why I think that classical and academic monasticism have much in common as long as it is genuine monasticism: where monastics try to maintain in themselves the spirit of devotion to God and His Church. Strictly speaking, we have negative examples in both classical and academic monasticism. And there are also very positive examples of those who more or less draw near to the high ideal of monastic life.

As for Fr. Mefody and I, at first we just wanted to join a monastery and we became learned monks only as an obedience, precisely because our father-confessor said that modern monks should be learned.

I think that these words of our elder, Fr. John Mironov, reflect the calling of monastics in the modern world. Even if a monastic is not in a theological educational institution, he must still participate in both the academic and the theological traditions and be familiar with many modern scholarly achievements.

—In your opinion, is it important for monastics to be educated, and what should be the average level of their education?

—Just to continue Fr. John’s thought, the modern monastic should be educated, because we live in the information age and people often (and in many ways rightly so) believe that someone who does not have information does not have the key to understanding what your mission is. If a modern person sees that his interlocutor is not familiar with many even simple things that are known to educated people, he loses authority in his eyes.

Education is important in two ways. Firstly, to have authority and show that you follow the path of the Gospel not just because you know nothing else. The Holy Fathers followed this tradition as well. For example, Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian knew “two streets” to the library and to the church. We know that St. Basil the Great later regretted having devoted too much time to secular wisdom, but nevertheless it was useful to him in the development of the theological formulations that were needed in that era.

Secondly, education is necessary for monastics because we now live in an advanced civilization. True, there are also rural monasteries, where monastics are very busy with physical labor, but gradually the volume of physical work has gets reduced, and even new agricultural devices appear. Time is freed up, and monastics are called to use it in order to become familiar with the entire history of the Church, the Lives of the saints, and all the Patristic wisdom, along with some secular knowledge that will help us glorify God and bear witness to God and the faith before unchurched people.

For monastics, education is also important because they are not always able to perform only the obedience of prayer. And educational activity and the accumulation of knowledge within your scope (each person has his own) is part of the work that the Lord blessed Adam and Eve to do: Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee… In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread (Gen. 3:18–19). St. Macarius the Great says that this sweat is not only physical, but also that of mental and spiritual labor, which every Christian, and especially a monastic, must shed on the path of the knowledge of God and self-knowledge.

—Vladyka, for a long time you pastored students, including foreign ones, at the St. Petersburg Theological Academy; you were the rector of the St. Nicholas-Ugresh Seminary in Dzerzhinsky near Moscow; and now you are the rector of the Moscow Theological Academy as an obedience. You observe the process when seminarians choose and go on their paths. Is it always a well-trodden path, which a young man understands that he needs to walk?

—I would say that seminarians have very different mentalities. There are those who are not yet fully aware of the choice they’ve made. Such a seminarian often matures in the course of training and after the beginning of practical parish life in some new status—not just as an acolyte or a reader, but a deacon or a priest.

An old priest of our academy who taught there for many years, Archpriest Alexander Kudryashov (he has five sons who are priests and five daughters who are priests’ wives), used to say that he saw many seminarians who were in an immature spiritual state. But gradually, step by step, if they did not lose the inner yardstick of the fear of God, these young people acquired real earnestness, awareness, and responsibility, and became good pastors.

But there are those who do not have this yardstick, and we usually have to send down those seminarians. They did not understand where they had come, and did not have something inside that they could be guided by. We simply say: “It is better for you to be a good parishioner, a good layman, and not take on yourself what you don’t feel to be your vocation.”

And, finally, there are those who are very mature and delight both your eye and your heart with their attitude to everything that happens—both to studies and obedience. They even participate in some new, additional, optional projects. Perhaps they need to be restrained so that they would not run too fast and take too much on their shoulders. This is a category of students in whom you see real active pastors who do not need to be reminded of anything. Rather, they themselves can undertake additional work and care for someone else, not only for themselves.

—Vladyka, as a father-confessor of many people who have become monastics or are willing to be tonsured, how do you see this vocation to monasticism to be felt and how is it born in a person?

—I usually say that bad is the soldier who has never dreamed of being a general, and bad is the Christian who has never dreamed of being a monastic.

—Father Mefody says the same.

—We are in agreement here, as in many other things (smiles). In general, of course, the mere birth of the idea of monastic life does not yet mean that you are called to it. It happens that a person wants to serve God but has not yet found the way to serve Him—his thoughts wander and split into two, and he is still searching. And then, sooner or later, he comes to understand that monastic life is not his path.

Or vice versa: to make sure whether it is truly your vocation, we turn to the Holy Fathers who taught that we can talk about the genuineness of your monastic path—the feeling that has appeared in your soul—when it was tested by time and your thoughts no longer wander; if you have been stable for long enough and this desire has taken root in you and lives a full life; if this desire does not ebb away in you, despite protracted stories, when you want to become a monastic, but this has not yet come true; and if you do not start running away to other monasteries, pursuing a quick tonsure, when you are told: “Test yourself for the time being, and we’ll test you.”

And this is precisely that moderate, but constant desire, which tests the depth and seriousness of the root that nourishes this intention in a human soul. This is how we determine from our human point of view whether it is blessed by God.

But there are some exceptions to this rule. For example, a person was thinking about something else, but his wife or husband (fiancé or fiancée ) dies, and the person finds himself in a state where he does not want to change the emotional attachment that he had to the former (or expected) marriage. And then he wants to devote himself to God in order to remain faithful to the Gospel ideal, according to which one should have only one spouse. And he unexpectedly begins to think about monastic life (unless, of course, he has no children or they have already grown up). Then it happens that the desire for monasticism is born unexpectedly and can mature very quickly.

—Does maturity have a time limit? And is there an average time limit?

—It depends. St. Maximus the Confessor said that the time limits are very relative and over the same period the soul of one person can change very much, while the soul of another person will not change like the soul of the first, even over a tenfold period.

Although there are certain time limits at monasteries and convents, they are relative. The main decision remains with the father-confessor or the abbess, or both of them, because every case is individual.

We know an example when the Venerable Pachomius the Great appointed the Venerable Theodore the Sanctified in his place, although he was younger than the monks who had lived under Pachomius for many years. This aroused the indignation of the older brethren. Pachomius replied: “If you trust me, then trust my blessing.”

In general, it should be at least a three-year period. Although Father Mefody and I believe, judging by the circle we communicate in, that the period should be yet longer—about five or seven years. But, of course, these things are very individual.

—What advice would you give to those who seek monastic life?

—First of all, I would advise getting acquainted with various monastic Patristic traditions: both Russian and Greek. Especially with the instructions of the monastics of holy life who lived not so long ago: the Optina Elders, the Glinsk Elders, and the elders of the Pskov-Caves. Both canonized and uncanonized monastic ascetics of holy life of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries have left many instructions.

Of course, it is imperative to communicate closely with your spiritual father, check your thoughts and self-esteem with him, receiving from him specific spiritual tasks for your gradual development.

In addition to reading, you should coordinate with your father-confessor the volume of prayer and service to others, in which we test our maturity or see our immaturity. Reading many patristic books and being in solitude and prayer, it is easy to imagine we are already spiritual people. And when faced with some even minor troubles in communicating with our neighbors, we quickly feel our imperfection, which is very useful for a beginner monastic worker, novice and rassaphore monk.

And, of course, you need to follow a certain golden mean. Do not put off everything until later and do not hurry too much, so that the pace of your spiritual “race” should be measured. When someone runs a marathon, he must choose an average pace so as not to get exhausted in the first half or in the middle of the distance.