In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

Orthodox Christianity is a difficult, uncomfortable and incomprehensible faith. It is difficult for the ignorant, inconvenient for the indolent and the conformists, and simply put, incomprehensible to those who do not want to understand it. Christianity, the religion of the cities, the religion of the educated and the sophisticated, has always received censure and blasphemy from the faceless crowd and from anonymous public opinion, from the powerful and the wise of this world.

Now you and I, dear brothers and sisters, are accused of various oddities and vices, but quite often it is rightly pointed out that we are disciples of Christ in name only, and with our lives, alas, not only do we not preach Christ the Savior, but it may even seem as if we are striving to undermine His good works altogether.

Our predecessors, the Christians of the first centuries, were accused by the crowds through rumors of sins completely inconceivable to us. “What harm have we done to you Greeks? Why do you hate those who follow the word of God, as if they were the worst villains?” asks Tertullian, a second-century apologist—that is, a defender of the faith—of the accusers of the Christians.

The historian Tacitus calls Christians ones who are “hated for their abominations”, for preaching pernicious superstition and being guilty of hatred of the human race. Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus viewed the Christians as “a race of men of a new and malignant superstition”. The writings of Celsus, Apuleius, and Lucian depict Christianity as a wicked and shameless sect of people for whom no law exists—neither divine nor human.

What was the reason for this attitude towards Christians on the part of the very tolerant and inclusive Rome? From its very first days the young Church of Christ has been persecuted, first by the Jews, then by the Gentiles. “An initiation to the Sacraments,” says Tertullian, “even in the case of pious men, requires the dismissal of the uninitiated”. The closed life of Christians had come to seem suspicious to those around them. If Christians were in hiding, it meant they were committing something reprehensible or downright criminal that truly needed to be hidden. The popular accusation was that they were atheistic: Christians did not have statues of gods and did not erect temples in honor of their God at the outset. The first Christians were also accused of carnal impurity, of having an Oedipus complex (this accusation was based on the well-known myth of Oedipus' marriage to his own mother).

And the pagans also accused the faithful disciples of Christ of participating in so-called Thyestean Feasts, that is, in cannibalism, eating human flesh.

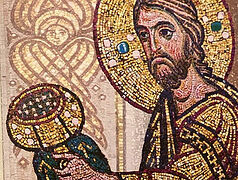

This is how the pagan crowd understood the great Sacrament of the Eucharist, the Communion of the Holy Body and Blood of Christ.

The first Christians could not imagine a worship service without the partaking of the Eucharist, or Communion. But from as early as the fourth century we hear the lamentable words of St. John Chrysostom: “In vain is the Liturgy served daily, in vain do we stand at the altar—for no one receives Communion. I say this not so that you may partake of Communion freely or whenever the opportunity simply arises, but so that you may make yourselves worthy. O thou man! Are you unworthy of receiving Communion? Then you are not worthy of hearing the prayers of the Liturgy”.

Twenty years ago it was thought that Communion should not be administered very often. This was also due to the tradition of the Synodal period of the Russian Orthodox Church, when every Orthodox Christian citizen of the Russian Empire was required to receive Communion at least once a year. An exponent of this tradition was, in particular, St. Philaret of Moscow: “The Church with its motherly voice urges all who are zealous of a reverent life to confess to one’s spiritual father and receive the Body and Blood of Christ four times a year or every month, and all others to do so at least once a year”. The names of communicants were recorded in special books, and those who violated this rule were subjected to various penalties; whereas those who frequently received Communion were sometimes suspected of sectarianism and untrustworthiness, as we can recall from the biography of St. Ignatius (Bryanchaninov).

We are now living in a time when a new tradition is taking shape, bringing us closer to the Christians of the first centuries. It is taking shape slowly, naturally, and without pressure from anyone. And how wonderful it is now to see you all gathered in church today, on Holy Thursday, the day God instituted the Sacrament of the Eucharist, in order for us to become united with our Creator through the partaking of His Immaculate Body and Blood.

By Divine Providence, people with the same goals and virtues are brought together in this life. And all of us, we who call ourselves disciples of Christ, through our love for Him, are unknowingly united with such similarly wonderful people, who in their life strive for goodness, toward the light and the truth. And it is remarkable to communicate, be friends with, and work together with people like that.

Christ, in His Flesh and Blood, unites us all in an extraordinary union, which is known as His Church. In this union, each of us has the opportunity to refine, correct, and transform our souls.

But it’s not just good like-minded people who come together. God also unites in this life people possessed by the same sins, weaknesses, and vices. Not so that they might devour one another through their passions of judgment, envy, and irritability, but so that they might become aware of their own unrighteousness, so that they may see themselves in the fellow sinner as in a mirror, come to acceptance of these things, humble themselves through their shortcomings, and then, instead of participating in a Thyestean Feast, that is, instead of feeding their soul with filth and uncleanness, filling it up with unnecessary things, they would come to the Lord's Feast, to the Divine Liturgy, in order to partake of the Body and Blood of Christ.

Let us remember, dear brothers and sisters, that to each of us, to me personally, whether good or bad, self-righteous or self-loathing, Christ has said: I am the living bread which came down from heaven: if any man eat of this bread, he shall live for ever: and the bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world... Whoso eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, hath eternal life; and I will raise him up at the last day. He that eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, dwelleth in me, and I in him. As the living Father hath sent me, and I live by the Father: so he that eateth me, even he shall live by me (Jn. 6:51, 54, 56-57).