In the mid-twentieth century, the English literary historian C. S. Lewis, the author of several apologetic works and religious broadcasts on the BBC, began to write fairy tales. Incredibly quickly—seven books in less than seven years—he created a whole epic about a magical land, Narnia, the name of which he had found on ancient maps.

In the mid-twentieth century, the English literary historian C. S. Lewis, the author of several apologetic works and religious broadcasts on the BBC, began to write fairy tales. Incredibly quickly—seven books in less than seven years—he created a whole epic about a magical land, Narnia, the name of which he had found on ancient maps.

The professor’s friend J. R. R. Tolkien, professor of languages and literature at Oxford University, was wary of Lewis’s fairy tales. It seemed to him that Lewis had piled up mythology, plots and meanings. But children immediately came to love the story of Narnia—they would read, re-read it and bombard the venerable professor with letters of gratitude and questions. And the professor answered many of them delicately and with great love.

The Chronicles of Narnia are still loved and read all over the world today. Some try to argue with the epic’s main idea, delving into the question, “What did the author want to say?” But in this case the author was unequivocal, and even children understand that the system of his allegories is about Christianity. Despite the fact that our post-Christian society thinks otherwise, Lewis wrote about Christ.

The allegorical image of Christ in The Chronicles of Narnia is the Great Lion Aslan. He appears whenever he likes, but always at the most important moments. He helps the characters understand what’s what and make right decisions. He is the creator and the foundation of Narnia—it is by him that it lives and breathes.

My children were struck by the iconic scene from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, when Aslan sacrificed himself for Edmund, and the weeping Susan and Lucy did not find his body on the stone altar. My seven-year-old son was the first to guess that it resembled the Passion, death and Resurrection of Christ, and my daughter remembered the Holy Saturday service, when we in tears had walked around the church, carrying the Holy Shroud.

And I thought of something else: how the lion Aslan, “the son of the Emperor-Over-the-Sea”, who created Narnia by singing, communicated with the creatures that dwelled in it. What words he said to them, what questions he asked! None was accidental, and each aptly hit the very soul.

Honesty and Repentance

Rumors always fly ahead of Aslan. Those who have not yet met him wait for this meeting with fear or joy, but not indifferently. It is impossible to be indifferent to the Great Lion, who knows everything about you.

Rumors always fly ahead of Aslan. Those who have not yet met him wait for this meeting with fear or joy, but not indifferently. It is impossible to be indifferent to the Great Lion, who knows everything about you.

Aslan is not a tame lion—this fact is mentioned in the book more than once. What does this mean? In addition to the literal meanings (talking, intelligent, strong, magical, great and mysterious), there is something more. Aslan is of a different nature than the other Narnia inhabitants. And his knowledge about everything and everyone is of a different quality.

The Great Lion could have revealed all his knowledge about the smallest movements of the human soul and put it on the table, like an accuser with irrefutable evidence in front of a suspect, looking with superiority at his fear.

But Aslan does not need fear, he does not need blind obedience. Why? First, because he infinitely loves all living creatures, despite their limitations. Secondly, he wants them not to lie—neither to themselves nor to him.

Being honest is hard. Often we, big and small, dodge and resort to guile, including towards ourselves. Especially towards ourselves because it’s scary to see your actions in all their glory.

Aslan gives the characters of the tales about Narnia such an opportunity. Without reproving or teaching them, he brings them to an answer. And they themselves answer—and shudder from their actions. And there is no point in pitying or justifying yourself, because Aslan’s voice is the voice of your conscience.

Aslan gives the characters of the tales about Narnia such an opportunity. Without reproving or teaching them, he brings them to an answer. And they themselves answer—and shudder from their actions. And there is no point in pitying or justifying yourself, because Aslan’s voice is the voice of your conscience.

“‘But where is the fourth?’ asked Aslan.

‘He has tried to betray them and joined the White Witch, O Aslan,’ said Mr. Beaver. And then something made Peter say,

‘That was partly my fault, Aslan. I was angry with him and I think that helped him to go wrong.’

“And Aslan said nothing either to excuse Peter or to blame him but merely stood looking at him with his great unchanging eyes. And it seemed to all of them that there was nothing to be said.”

Peter courageously plunges into his own soul, finds guilt before his brother there and pulls it out into the light. He does not justify himself, although he could have done this: His brother betrayed everyone, gave them up to the White Witch, and defected to her. But Peter cannot be cunning under Aslan’s serene gaze—and he offers him repentance. Aslan accepts it. He accepts all who are ready to come.

Repentance is one of the key ideas in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the fifth book about Narnia. Eustace appears in it—the arrogant, funny, ridiculous, absolutely disagreeable and terribly lonely cousin of the main characters.

It seems that Eustace cannot accept Narnia with its fairy-tale heroes and laws. In fact, Eustace does not accept what is alien to him: trust, faithfulness and courage. He finds the dragon’s treasure very appealing though.

With this a series of purifying sufferings of Eustace begins. In the dragon’s body he feels even worse than before. But it is difficult circumstances that change the boy.

The apotheosis is Eustace’s account after he had returned into his own body, about his painful and saving meeting with Aslan.

“‘I wasn’t afraid of the lion eating me, I was just afraid of it—if you can understand. Well, it came close up to me and looked straight into my eyes. And I shut my eyes tight. But that wasn’t any good because it told me to follow it.’

‘You mean it spoke?’

‘I don’t know. Now that you mention it, I don’t think it did. But it told me all the same. And I knew I’d have to do what it told me, so I got up and followed it.’”

Aslan peeled away the dragon scales from Eustace. Through unbearable pain the character comes to his real self—the one who hid under the hideous skin that had grown over the years. If it were not for the Great Lion and the desire of Eustace himself, this would not have happened.

Aslan peeled away the dragon scales from Eustace. Through unbearable pain the character comes to his real self—the one who hid under the hideous skin that had grown over the years. If it were not for the Great Lion and the desire of Eustace himself, this would not have happened.

The intention (turning into necessity) to get to the very essence, to the shameful depths of the soul, to the unsightly reasons for their actions, is characteristic of the key characters of the tales about Narnia. They are not perfect, not sinless, not always honest and courageous. But they are willing to improve. Aslan helps them, and they love him simply for what he is, like a Father figure.

“‘Son of Adam,’ said the Lion. ‘There is an evil Witch abroad in my new land of Narnia. Tell these good Beasts how she came here.’

“A dozen different things that he might say flashed through Digory’s mind, but he had the sense to say nothing except the exact truth.

‘I—I brought her, Aslan,’ he answered in a low voice.

‘For what purpose?’

‘I wanted to get her out of my own world back into her own. I thought I was taking her back to her own place.’

‘How came she to be in your world, Son of Adam?’

‘By—by Magic.’

“The Lion said nothing and Digory knew that he had not told enough...

‘You met the Witch?’ said Aslan in a low voice which had the threat of a growl in it.

‘She woke up,’ said Digory wretchedly. And then, turning very white, ‘I mean, I woke her. Because I wanted to know what would happen if I struck a bell. Polly didn’t want to. It wasn’t her fault. I—I fought her. I know I shouldn’t have. I think I was a bit enchanted by the writing under the bell.’

‘Do you?’ asked Aslan; still speaking very low and deep.

‘No,’ said Digory. ‘I see now I wasn’t. I was only pretending.’”

Keep your attention on yourself

Every meeting with the Great Lion in the Chronicles of Narnia is always a real event. The characters remember them forever and even change their way of life. Sometimes a short dialogue with Aslan reveals things that are not obvious at first glance, but are extremely important.

In the Patericon there is an account of how the Venerable Anthony the Great heard a voice saying: “Anthony! Keep your attention on yourself!” The Great Lion conveys the same idea to the book’s characters. And it is an important idea, which returns the focus of your attention to your own moral life, and not to the echoes of someone else’s.

“‘Then it was you who wounded Aravis?’

“‘It was I.’

“‘But what for?’

“‘Child,’ said the Voice, ‘I am telling you your story, not hers. I tell no one any story but his own.’”

Delicately yet firmly, Aslan brings the characters’ thoughts back to the most important point—inside their souls. It’s hard; it would be easier to make excuses or gossip about others, but it’s impossible to fool Aslan.

Delicately yet firmly, Aslan brings the characters’ thoughts back to the most important point—inside their souls. It’s hard; it would be easier to make excuses or gossip about others, but it’s impossible to fool Aslan.

“‘Yes, wasn’t it a shame?’ said Lucy. ‘I saw you all right. They wouldn’t believe me. They’re all so…’

“From somewhere deep inside Aslan’s body there came the faintest suggestion of a growl.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Lucy, who understood some of his moods. ‘I didn’t mean to start slanging the others. But it wasn’t my fault anyway, was it?’

“The Lion looked straight into her eyes.

“‘Oh, Aslan,’ said Lucy. ‘You don’t mean it was? How could I—I couldn’t have left the others and come up to you alone, how could I? Don’t look at me like that… oh well, I suppose I could... But what would have been the good?’”

Under the Great Lion’s gaze the characters of stories about Narnia give up even trying to think about what others are like. And suddenly it turns out that answers to many questions are hidden in this inner silence.

“‘And what ever am I to say to him?’

“‘Perhaps you won’t need to say much,’ Lucy suggested.”

Faith and trust

Another important theme in the Chronicles of Narnia is faith. The existence of Aslan, like the fairytale land’s past, is questioned more than once. And something amazing happens: faith does not follow miracles, but miracles are performed as a reward for faith.

Faith is a key theme in the book Prince Caspian of the Narnia series. Many of its characters do not believe in the existence of Aslan, and Peter, Susan and Edmund do not believe in his return. Only little Lucy sees the Great Lion because she does not doubt him for a minute.

Prince Caspian believes in Aslan as well. The rightful heir to the throne, he hides from his traitorous uncle; and, although he knows little, he firmly keeps what he was taught. That’s why he becomes a real king.

“‘But who believes in Aslan nowadays?’

“‘I do,’ said Prince Caspian.”

In general, the characters of the Chronicles of Narnia may err and doubt, but they wholeheartedly trust the Great Lion. That’s why he comes to their aid. However, Aslan does not impose himself on those who hate or fear him. For example, on the dwarves from the last book, who sit on a sunny lawn and are sure that they are in a dark barn.

Correspondence with Laurence’s mother

“‘Son,’ said Aslan to the Cabby. ‘I have known you long. Do you know me?’

‘Well, no, sir,’ said the Cabby. ‘Leastways, not in an ordinary manner of speaking. Yet I feel somehow, if I may make so free, as though we’ve met before.’”

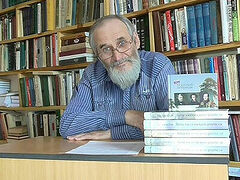

Clive Staples Lewis Many letters from readers of The Chronicles of Narnia to the author, along with his answers, have survived. As you read them you marvel at Lewis’s careful attention to children’s opinions and impressions. But the letter of little Laurence Krieg from America stands out: The boy confesses that he loves Aslan more than Christ. Here is what the writer answers to Laurence’s mother:

Clive Staples Lewis Many letters from readers of The Chronicles of Narnia to the author, along with his answers, have survived. As you read them you marvel at Lewis’s careful attention to children’s opinions and impressions. But the letter of little Laurence Krieg from America stands out: The boy confesses that he loves Aslan more than Christ. Here is what the writer answers to Laurence’s mother:

“Dear Mrs. Krieg,

“Tell Laurence from me, with my love:

“1) Even if he was loving Aslan more than Jesus (I’ll explain in a moment why he can’t really be doing this) he would not be an idol-worshipper. If he was an idol worshipper he’d be doing it on purpose, whereas he’s now doing it because he can’t help doing it, and trying hard not to do it. But God knows quite well how hard we find it to love Him more than anyone or anything else, and He won’t be angry with us as long as we are trying. And He will help us.

“2) But Laurence can’t really love Aslan more than Jesus, even if he feels that’s what he is doing. For the things he loves Aslan for doing or saying are simply the things Jesus really did and said. So that when Laurence thinks he is loving Aslan, he is really loving Jesus: and perhaps loving Him more than he ever did before. Of course there is one thing Aslan has that Jesus has not—I mean, the body of a lion. (But remember, if there are other worlds and they need to be saved and Christ were to save them—as He would—He may really have taken all sorts of bodies in them which we don’t know about.) Now if Laurence is bothered because he finds the lion-body seems nicer to him than the man-body, I don’t think he need be bothered at all. God knows all about the way a little boy’s imagination works (He made it, after all) and knows that at a certain age the idea of talking and friendly animals is very attractive. So I don’t think He minds if Laurence likes the Lion-body. And anyway, Laurence will find as he grows older, that feeling (liking the lion-body better) will die away of itself, without his taking any trouble about it. So he needn’t bother.

“3) If I were Laurence I’d just say in my prayers something like this: ‘Dear God, if the things I’ve been thinking and feeling about those books are things You don’t like and are bad for me, please take away those feelings and thoughts. But if they are not bad, then please stop me from worrying about them. And help me every day to love You more in the way that really matters far more than any feelings or imaginations, by doing what You want and growing more like You.’ That is the sort of thing I think Laurence should say for himself; but it would be kind and Christian-like if he then added, ‘And if Mr. Lewis has worried any other children by his books or done them any harm, then please forgive him and help him never to do it again.’

“Will this help? I am terribly sorry to have caused such trouble, and would take it as a great favor if you would write again and tell me how Laurence goes on. I shall of course have him daily in my prayers. He must be a corker of a boy: I hope you are prepared for the possibility he might turn out a saint. I daresay the saints’ mothers have, in some ways, a rough time!

“Yours sincerely,

C. S. Lewis

[June 3, 1955]”1

Aslan is an allegory, a fairytale image of Christ, applicable only to the fairyland of Narnia, to Lewis’ books. However, Aslan always leads the characters to important things that are difficult, but necessary to realize if you are a Christian. Why did I do it this way? How should I have done it? How can I improve? Aslan teaches you to listen to yourself and love others.

“‘Are—are you there [on earth] too, Sir?’ said Edmund.

“‘I am,’ said Aslan. ‘But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.’”