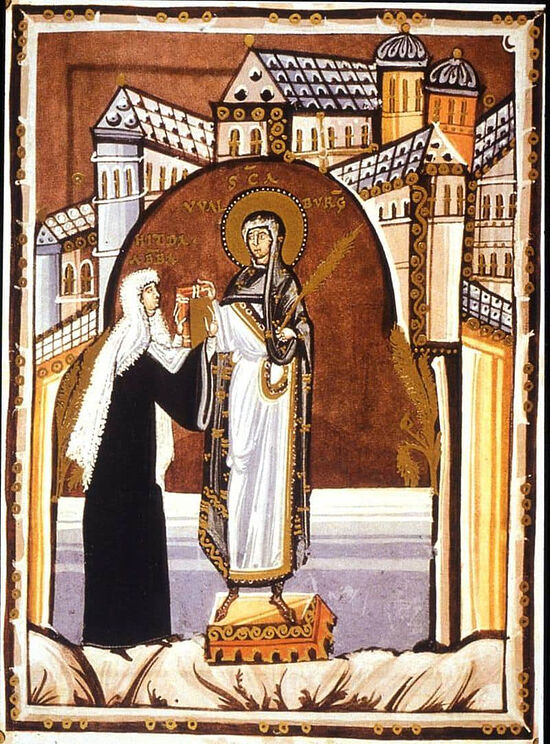

The earliest depiction of St. Walburga, from the 11th century Hitda Codex

The earliest depiction of St. Walburga, from the 11th century Hitda Codex

Women Martyrs

St. Ursula of Cologne (†c. 383) and her companions

St. Afra of Augsburg (†c. 304)

St. Wiborada (†926)

The Orthodox history of the German lands (present day Germany, Austria, and Switzerland) is quite ancient and boasts a multitude of saints. This area of Orthodox Christian history, often viewed purely through a post-Schism lens, warrants and richly rewards deeper investigation. This write-up will take a quick look at three holy women, martyrs who graced those lands and whose legacy of sanctity will forever remain.

St. Ursula of Cologne One of the most enduringly beloved saints of the German lands is the virgin-martyr St. Ursula, though little is now known about her. She was a Roman-Briton princess who found herself betrothed to a pagan from Armorica, an ancient kingdom in what’s now northern France. She persuaded him to accept baptism, and additionally obtained his permission to travel to various holy places on the European continent prior to their wedding. Accordingly she set off for Rome and, after having spent some time there, proceeded to Cologne, where her wedding was to be held. However, perhaps unbeknownst to her, Cologne at that time was being besieged by the Huns. Arriving with her retinue, which according to some accounts numbered as many as 11,000, she and her entire company, including her betrothed, were martyred by the infidel horde. This took place sometime in the late 4th century. St. Ursula’s feast day is October 21.

St. Ursula of Cologne One of the most enduringly beloved saints of the German lands is the virgin-martyr St. Ursula, though little is now known about her. She was a Roman-Briton princess who found herself betrothed to a pagan from Armorica, an ancient kingdom in what’s now northern France. She persuaded him to accept baptism, and additionally obtained his permission to travel to various holy places on the European continent prior to their wedding. Accordingly she set off for Rome and, after having spent some time there, proceeded to Cologne, where her wedding was to be held. However, perhaps unbeknownst to her, Cologne at that time was being besieged by the Huns. Arriving with her retinue, which according to some accounts numbered as many as 11,000, she and her entire company, including her betrothed, were martyred by the infidel horde. This took place sometime in the late 4th century. St. Ursula’s feast day is October 21.

St. Ursula’s name means “little bear,” perhaps referring to her birth in a caul (but this is speculative). She was renowned for her beauty and exquisite gracefulness of manner. The Virgin Islands are named in her honor.

St. Alfra's martyrdom Somewhat earlier than St. Ursula, the life and struggles of St. Afra played out. With St. Ulrich (see later), she is the co-patron of Augsburg. St. Afra may originally have been from Cyprus. She was born to pagan parents and was dedicated at birth to the service of Venus. She may even have worked in a brothel run by her family for a time. However, she was not long to remain in such darkness and iniquity. During the persecutions under Diocletian, the local bishop Narcissus was compelled to take refuge with St. Afra and her mother. He soon converted their whole family to the faith of Christ. Upon later being herself denounced as a Christian to the authorities, she boldly refused the emperor’s order to sacrifice to the pagan gods, instead fearlessly proclaiming Christ. For her brave confession, she was publicly burned by the Lech River (other sources say she was beheaded). St. Afra entered the heavenly kingdom around the year 304.

St. Alfra's martyrdom Somewhat earlier than St. Ursula, the life and struggles of St. Afra played out. With St. Ulrich (see later), she is the co-patron of Augsburg. St. Afra may originally have been from Cyprus. She was born to pagan parents and was dedicated at birth to the service of Venus. She may even have worked in a brothel run by her family for a time. However, she was not long to remain in such darkness and iniquity. During the persecutions under Diocletian, the local bishop Narcissus was compelled to take refuge with St. Afra and her mother. He soon converted their whole family to the faith of Christ. Upon later being herself denounced as a Christian to the authorities, she boldly refused the emperor’s order to sacrifice to the pagan gods, instead fearlessly proclaiming Christ. For her brave confession, she was publicly burned by the Lech River (other sources say she was beheaded). St. Afra entered the heavenly kingdom around the year 304.

A final woman martyr of note came from much later times: The holy nun-martyr St. Wiborada. She lived during the late ninth–early tenth centuries.

St. Wiborada the nun-martyr St. Wiborada was an anchoress, pursuing a life of prayer as a solitary Benedictine nun. Of wealthy and noble lineage from Swabia (southern Germany), St. Wiborada forsook all worldly wealth and followed her brother Hatto into monasticism at the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland. Here she occupied herself with various useful crafts.

St. Wiborada the nun-martyr St. Wiborada was an anchoress, pursuing a life of prayer as a solitary Benedictine nun. Of wealthy and noble lineage from Swabia (southern Germany), St. Wiborada forsook all worldly wealth and followed her brother Hatto into monasticism at the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland. Here she occupied herself with various useful crafts.

After being falsely accused of some unspecified major infraction, for which she was cruelly subjected to trial by ordeal, St. Wiborada retreated from communal life for a hermetic existence. She acquired great spiritual gifts, including prophecy and the ability to heal diseases. A certain girl named Richaldis, who the saint healed of some grievous disease, stayed on with her as her disciple. St. Ultich of Augsburg (see later), came often to her for counsel and she prophesied his great future spiritual attainments.

St. Wiborada prophetically foretold a coming Magyar invasion, giving the nearby monastics time to hide their holy objects, manuscripts, and valuables and to flee from harm. She herself chose not to flee. When the Magyar invaders arrived, they burst into her cell as she was kneeling in prayer, and one of them split open her skull with his axe. Thus did St. Wiborada pass into eternal glory as a holy anchoress and martyr in the year 926.

These holy women collectively constitute a brilliant part of the tapestry of Orthodox Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. May we have their prayers!

Missionaries and Enlighteners

St. Boniface of Mainz (+c.754)

St. Burchard of Wurzburg (+c.752)

St. Rupert of Salzburg (+710)

St. Magnus of Füssen (+c.772)

St. Gall (+c.646) and St. Deicolus (+625)

Though Christianity had certainly been present in the German lands long before (as witnessed by the lives and martyric struggles of Saints Afra and Ursula, et al), the full conversion and enlightenment of this area was principally the work of the great St. Boniface, one of the Church’s most renowned missionary saints.

St. Boniface, Enlightener of Germany St. Boniface was an Englishman, born in Devonshire. Blessed with an excellent mind, he pursued monasticism in a Benedictine monastery of Adescancastre, where he produced England’s first Latin grammar. From early on he had a great missionary zeal, a common feature among pre-Schism English and Celtic saints. He set out on a mission to evangelize the Frisians, but external factors frustrated the mission.

St. Boniface, Enlightener of Germany St. Boniface was an Englishman, born in Devonshire. Blessed with an excellent mind, he pursued monasticism in a Benedictine monastery of Adescancastre, where he produced England’s first Latin grammar. From early on he had a great missionary zeal, a common feature among pre-Schism English and Celtic saints. He set out on a mission to evangelize the Frisians, but external factors frustrated the mission.

After being blessed by the pope to commence a new mission, whereupon his name was changed from Winfrid to Boniface, he set out to evangelize the German lands, where he would organize their church life and serve as their first bishop. Showing amazing boldness in his commission, St. Boniface astonished the people by felling an oak tree dedicated to the pagan god Thor and building a chapel with its wood. Elevated to Archbishop, he baptized thousands. He founded multiple bishoprics and monastic establishments. Having accomplished so much, with enduring results, in Germany, St. Boniface set out once more to convert the Frisians, but was martyred by locals in about the year 754. He is commemorated as the Apostle to the Germans.

St. Burchard of Wurzburg Among the many holy men assisting St. Boniface in his apostolic labors was St. Burchard. He, too, was of English birth. Not part of the original mission, he came later, after St. Boniface was established as archbishop, but proved himself most zealous and capable. He was consecrated bishop of Wurzburg, in which capacity he served with great holiness until his repose in 752. He gained widespread esteem and advised popes and kings. His feast is celebrated on October 14. Also of note among the assistants to St. Boniface is St. Sturm, or Sturmi (†779), founder and first abbot of the important Fulda Monastery in Hesse, central Germany.

St. Burchard of Wurzburg Among the many holy men assisting St. Boniface in his apostolic labors was St. Burchard. He, too, was of English birth. Not part of the original mission, he came later, after St. Boniface was established as archbishop, but proved himself most zealous and capable. He was consecrated bishop of Wurzburg, in which capacity he served with great holiness until his repose in 752. He gained widespread esteem and advised popes and kings. His feast is celebrated on October 14. Also of note among the assistants to St. Boniface is St. Sturm, or Sturmi (†779), founder and first abbot of the important Fulda Monastery in Hesse, central Germany.

Another of the great enlighteners of the German lands was St. Rupert of Salzburg, known as the Apostle to Bavaria and Austria. Born into the Frankish nobility, he was made Bushop of Worms for his holy life and sober discernment. He was deeply ascetic and gave everything to the poor. People came from all around to receive his teachings and counsels, and he had the grace of working miracles. But wicked and unbelieving men rose up against him and cast him out, beating and exiling him.

Providentially, the Duke of Bavaria, Theodo, hearing of the blessed one’s great reputation, invited St. Rupert to visit his realms and instruct his benighted people in the Faith of Christ. St. Rupert hastened thence and, upon arriving in Regensburg, he did not pause to rest from his exhausting journey but immediately set about instructing the duke and his court in the words of salvation. Having baptized many, he set sail down the Danube River, going as far as Pannonia, enlightening and baptizing multitudes and delivering them from the terrible worship of idols.

St. Rupert of Salzburg, Enlightener of Bavaria and Austria St. Rupert was consecrated bishop and founded churches and other religious establishments around Bavaria. One of these was founded in a miraculous way, being marked out by holy lights shining in a wilderness spot. St. Rupert had a cross he had personally made and blessed placed there, and in confirmation of the miracle, the cross rose and traveled until it stood above St. Rupert’s episcopal residence! A monastery was soon erected at the site.

St. Rupert of Salzburg, Enlightener of Bavaria and Austria St. Rupert was consecrated bishop and founded churches and other religious establishments around Bavaria. One of these was founded in a miraculous way, being marked out by holy lights shining in a wilderness spot. St. Rupert had a cross he had personally made and blessed placed there, and in confirmation of the miracle, the cross rose and traveled until it stood above St. Rupert’s episcopal residence! A monastery was soon erected at the site.

After the death of Theodo, St. Rupert continued his missionary activities as well as the establishment of churches and monasteries. He based his activities in the old Roman city of Juvavia (present day Salzburg) on the Salzach River. Here he established a great monastic foundation that was presided over by his pious niece, St. Ermentrude. He also established a foundation in honor of St. Maximilian of Lorch, an early missionary and martyr to the region (which back then was called Noricum).

St. Rupert passed his remaining years in piety and apostolic labors. Shortly after Lent in the year 710, he foresaw his end and committed his bishopric to his successor, St. Vitalis of Salzburg, and peacefully reposed.

A final great converter/enlightener figure who must be noted is St. Magnus of Füssen. He is remembered as the Apostle to the Allgäu, a region of extreme southern Germany and northern Austria. Not much is known now about St. Magnus, but it is believed he was a pupil of the great monastic founders Saints Columbanus and Gall (see below), or was a contemporary of St. Boniface. (As the Orthodox sources list his date of repose between the years 750–772, we will go with the latter chronology).

Saints Gall, Columbanus, and Magnus At the invitation of a certain priest Tozzo of Augsburg, St. Magnus traveled to that area where the bishop of Augsburg charged him with the evangelization of the Allgäu region. There the holy man brought the word of God to the people while living in a solitary cell in the forest across the River Lech. A large monastery was subsequently built over the site of his cell, which was later named St. Mang’s in his honor.

Saints Gall, Columbanus, and Magnus At the invitation of a certain priest Tozzo of Augsburg, St. Magnus traveled to that area where the bishop of Augsburg charged him with the evangelization of the Allgäu region. There the holy man brought the word of God to the people while living in a solitary cell in the forest across the River Lech. A large monastery was subsequently built over the site of his cell, which was later named St. Mang’s in his honor.

A final note should be made of certain key monastic missionaries to the German lands, especially the aforementioned St. Gall, disciple of the Irish missionary St. Columbanus.

St. Columbanus was a disciple of the strictly ascetic St. Comgall at Bangor Abbey in northern Ireland in the late 6th-early 7th century. With 12 companions he travelled to the European mainland to spread Irish monastic disciplines there. One of these companions was St. Gall (though the two may have only joined up on the continent, at Luxeuil). Another was the elder brother of St. Gall, St. Deicolus (or Domgall), who went on to do missionary work in France.

As a disciple of St. Columbanus, reared in the stern tradition of Bangor Abbey , St. Gall naturally brought a strong ascetic emphasis with him. He also, significantly, acquired a strong emphasis on learning, as Bangor was a renowned educational center. After accompanying St. Columbanus from Luxeuil into exile in Alemannia, St. Gall was forced for reasons of ill health from accompanying him any further. Settling in a cell near Lake Constance, he pursued an ascetic life as a hermit. He was noted for his forceful preaching. In his old age he was offered the bishopric of Constance , which he declined. He also declined an offer of the abbacy of the monastery of Luxeuil.

St. Gall’s name is perhaps best known now for the abbey founded on the location of his hermitage in present day Switzerland. The Abbey of St. Gall, named for him, was a major monastic center and boasted one of the largest monastic libraries in the world.

St. Gall reposed in peace around the year 646 and was immediately revered as a saint. People prayed at his tomb and received healings of their afflictions.

May the holy Enlighteners and missionary monks of the German lands intercede for us!

Right-Believing Queens

St. Radegund of Thuringia (†587)

St. Matilda of Ringelheim (†968)

In our account of the Orthodox history of the German lands, a couple of royal women of exceptional holiness are worthy of note: St. Radegund of Thuringia and St. Matilda of Ringelheim.

St. Radegund of Thuringia Although St. Radegund is overwhelmingly associated with areas within modern day France, she was of Thuringian origin. At that time Thuringia, now part of central Germany, was part of the Frankish kingdom, which spanned both present day Germany and France (and beyond).

St. Radegund of Thuringia Although St. Radegund is overwhelmingly associated with areas within modern day France, she was of Thuringian origin. At that time Thuringia, now part of central Germany, was part of the Frankish kingdom, which spanned both present day Germany and France (and beyond).

St. Radegund was a princess, and as befitted one of her high birth she was extremely well educated. In later life she cultivated a literary friendship with the great Christian poet St. Venantius Fortunatus (+610). The great bishop and historian St. Gregory of Tours (†594) was also on close terms with St. Radegund and wrote extensively about her holy life in his work, History of the Franks.

Court life in the Frankish kingdom was exceedingly brutal, with near constant fratricidal wars and killings as various parties endlessly contended for power. After her father was killed by her uncle, who himself was later conquered, St. Radegund ended up as one of king Clotaire I’s six wives. After Clotaire had her brother killed, she fled his court and devoted herself fully to the Church. She used her means to found the Sainte-Croix Abbey in Poitiers, so named for a portion of the True Cross which she had obtained from the Byzantine emperor.

St. Radegund was notable for her extreme asceticism, which included a severely abstemious diet. During Lent she consumed only water. She wore heavy iron chains that cut her flesh. For her pains she gained great spiritual gifts, including the gift of healing illnesses through her prayers. St. Radegund reposed in 587. Jesus College, Cambridge, acknowledges her as one of its patron saints.

St. Matilda of Ringelheim Centuries after St. Radegund, St. Matilda of Ringelheim lived in great holiness as a member of the highest royalty. St. Matilda was a Saxon queen, the first of the Ottonian dynasty (so named for her son, Otto the Great) of the Holy Roman Empire.

St. Matilda of Ringelheim Centuries after St. Radegund, St. Matilda of Ringelheim lived in great holiness as a member of the highest royalty. St. Matilda was a Saxon queen, the first of the Ottonian dynasty (so named for her son, Otto the Great) of the Holy Roman Empire.

She married Henry, Duke of Saxony, by whom she had five children, including the aforementioned Otto. As queen she was especially noted for her sense of justice and patronage of monasteries, especially those for women. Of particular importance was her founding of Quedlinburg Abbey in Saxony. Many noble ladies were reared within that important convent.

St. Matilda reposed in the year 968 in the convent in Quedlinburg that she had founded. Her lifelong charity and monastic patronage were much renowned, and she was venerated as a saint.

Royal saints such as Radegund and Matilda show that even privileged birth is not an impediment to salvation if one sincerely seeks God. May these holy royal women saints of the German lands pray to God for us!

A Family of Saints

St. Willibald of Eichstätt (†c.787)

St. Winibald of Heidenheim (†761)

St. Walburga of Heidenheim (†c.779)

Earlier we looked briefly at the apostolic labors of St. Boniface, the enlightener par excellence of the German lands. Brief attention was also given to one of the main helpers in his great evangelization work, St. Burchard.

Naturally, St. Boniface had others assisting him in his task. Particularly outstanding among them were certain members of his own family, two nephews and a niece of his: the siblings Saints Willibald, Winibald, and Walburga.

St. Willibald of Eichstätt St. Willibald was, like St. Boniface and the rest of that holy family, from Crediton in Devonshire, England. Both of his parents are also saints: St. Richard the Pilgrim (+720) and St. Wuna of Wessex (+710). (St. Wuna is believed to have been St. Boniface’s sister).

St. Willibald of Eichstätt St. Willibald was, like St. Boniface and the rest of that holy family, from Crediton in Devonshire, England. Both of his parents are also saints: St. Richard the Pilgrim (+720) and St. Wuna of Wessex (+710). (St. Wuna is believed to have been St. Boniface’s sister).

In his youth St. Willibald was much traveled, accompanying his father and brother on an extensive religious pilgrimage over Europe. During this journey St. Richard reposed. The brothers continued on, venerating the holy sites in Rome, and at some point became ill with the plague. They managed to tend to each other and after much prayer were miraculously cured of their seemingly terminal condition.

St. Winibald stayed on as a monk in Rome, but St. Willibald continued on to Palestine (by way of Ephesus and Cyprus), thus becoming the first Englishman to visit the Holy Land. Afterwards he sojourned for two years in Constantinople. Moving on yet again, he joined the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy. However, his uncle, St. Boniface, petitioned Pope Gregory III that Willibald be sent to assist him in evangelizing the Germans, which was granted.

In Eichstätt he was ordained to the priesthood by his uncle, after which he began spreading the gospel in that area. He then briefly sojourned in Thuringia, where he was reunited after a long separation with his brother, Winibald. Together the brothers returned to Eichstätt and founded the double monastery (i.e., both a male and female community) in Heidenheim. St. Winibald served there as first abbot until his repose in 761, and was succeeded in the abbacy by their sister, St. Walburga.

St. Willibald was made bishop of Eichstätt and passed his days in episcopal and apostolic service throughout the region of Franconia for over forty years, before reposing around the year 787.

St. Winibald has already been discussed above, but in addition to the deeds already herein noted it should be further mentioned that he had charge of seven churches, he additionally established a monastery at Schwanfeld, and he participated in the Concilium Germanicum. The Concilium, over which St. Boniface presided, was the first Church synod ever held in that region; it addressed such matters as church property, clergy guidelines, and monastic rules. St. Winibald was also active in a religious confraternity under St. Chrodegang (†766).

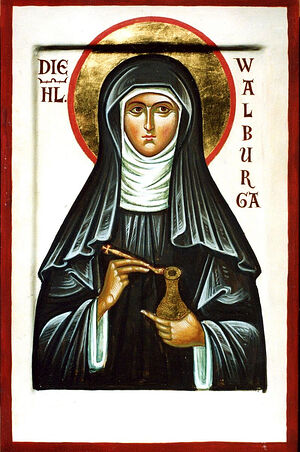

St. Walburga St. Walburga, the sister and apparently the youngest of the three, was one of the most remarkable women of her era. She has remained for centuries one of Central Europe’s most enduringly venerated saints.

St. Walburga St. Walburga, the sister and apparently the youngest of the three, was one of the most remarkable women of her era. She has remained for centuries one of Central Europe’s most enduringly venerated saints.

She was brought up and educated from the age of eleven at Wimborne Abbey in Dorset, England. Taking monastic tonsure, she remained at this renowned and widely esteemed monastery for 26 years, where she acquired skills in crafts and a fine education.

At a certain point she set out from England and joined her brothers in Germany to help them assist St. Boniface’s missionary work there. Displaying her fine literary skills, she wrote (in Latin) a life of her brother and an account of his travels in the Holy Land. For this reason she is sometimes considered the first female author of both England and Germany.

St. Walburga succeeded her brother St. Winibald as head of the double monastic community of Heidenheim upon his repose. She held this position for a number of years, leading the community with great wisdom and holiness, until her repose around the year 779. In the 9th century her relics were transferred to Eichstätt, and for centuries they have exuded a fragrant, therapeutic myrrh through which many miracles have occurred.

May all the members of this saintly family continue to intercede for our lands and for all the faithful.

Holy Hierarchs of the Tenth Century

St. Ulrich of Augsburg (†973)

St. Wolfgang of Regensburg (†994)

St. Conrad of Constance (†975)

A trio of holy hierarchs brings this survey of Orthodoxy in the German lands right up to almost the eve of the Schism. These men led holy lives and guided their respective flocks in piety, wisdom, and righteousness during this twilight period of Western Orthodoxy.

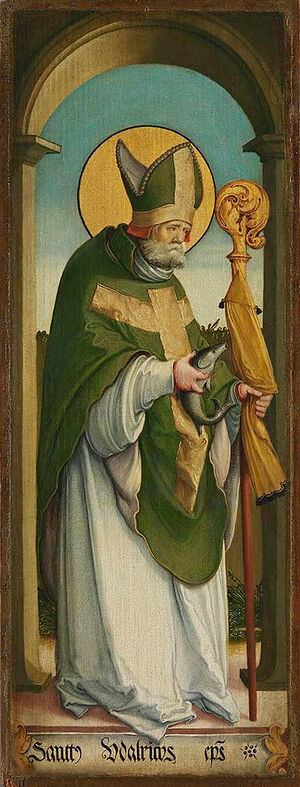

St. Ulrich of Augsburg St. Ulrich of Augsburg was of noble stock, related to the Ottonian dynasty. Born in Zurich, he was a descendant of counts and dukes. From childhood he was dedicated to the service of God as an oblate, and from age seven was raised in the monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland. Here he distinguished himself for his quick and extensive learning. Significantly, he came under the spiritual tutelage of the holy anchoress St. Wiborada (discussed in a previous post). She prophetically foretold his future service as bishop.

St. Ulrich of Augsburg St. Ulrich of Augsburg was of noble stock, related to the Ottonian dynasty. Born in Zurich, he was a descendant of counts and dukes. From childhood he was dedicated to the service of God as an oblate, and from age seven was raised in the monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland. Here he distinguished himself for his quick and extensive learning. Significantly, he came under the spiritual tutelage of the holy anchoress St. Wiborada (discussed in a previous post). She prophetically foretold his future service as bishop.

In 923 St. Ulrich was indeed made bishop, just as St. Wiborada had foretold, when Henry I of Germany appointed him Bishop of Augsburg in Swabia, the far south of Germany. Finding both the moral and material condition of his diocese at low ebb, he set about extensive reforms and projects. Churches, schools, and monasteries were rebuilt, and new ones were constructed as well. Clergy training and discipline improved. On separate pilgrimages to Rome holy relics were obtained for the spiritual enrichment of the religious establishments in his realm. And, when circumstances forced him to intervene in political matters, he helped obviate a potential bloody war by negotiating peace between king Otto I (“the Great”) and his rebellious son, Liudolf. St. Ulrich also participated in numerous Church synods.

As mentioned earlier in the account of St. Wiborada’s martyrdom, a Magyar (Hungarian) invasion devastated that region at this time. Here St. Ulrich especially distinguished himself, building protective walls around Augsburg and rebuilding ravaged churches in the area. He contributed vitally both materially and spiritually to the defense of the city, riding out to the city gates in the midst of the Magyar siege and intoning Psalms. His efforts were invaluable in bolstering defenses and contributing to the ultimate defeat of the invaders, though as a man of the cloth St. Ulrich did not himself participate in the fighting.

In his later years, angels were seen assisting St. Ulrich in celebrating Mass. He retired to the monastery of Ottobeuren in Bavaria where he passed his remaining days in holiness. On the morning of his repose in the year 973 he had ashes and holy water sprinkled on the ground in a cross shape, upon which he lay down. He then gave up his holy soul as the clergy chanted the Litany.

St. Wolfgang of Regensburg St. Wolfgang of Regensburg was also of noble stock, from a family of Swabian counts. He spent his childhood at the famed Reichenau Abbey on Lake Constance, where presumably he received an excellent education and fine religious instruction.

St. Wolfgang of Regensburg St. Wolfgang of Regensburg was also of noble stock, from a family of Swabian counts. He spent his childhood at the famed Reichenau Abbey on Lake Constance, where presumably he received an excellent education and fine religious instruction.

He later moved to Trier at the behest of the archbishop there, where he labored in the cathedra school and attempted, amid much resistance, to reform certain aspects of the archdiocese. He came into the orbit of the Abbey of St. Maximin, and also made the acquaintance of the great missionary St. Adalbert of Prague (†997).

Moving on to a Benedictine monastery in Switzerland, St. Wolfgang was elevated to the priesthood by St. Ulrich. At St. Ulrich’s and Emperor Otto’s request, he undertook a mission to the Magyars of Pannonia, an historic region of Central Europe including parts of modern Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Austria, and other countries.

On Christmas Day in the year 972 St. Wolfgang was made bishop of Regensburg in Bavaria. He performed many important functions in this role, serving as tutor to Emperor Henry II and implementing monastic reforms. He also participated in various deliberative assemblies as an advisor to Emperor Otto II.

However, the vagaries of political life led him, as an unworldly man concerned with spiritual matters, to withdraw into reclusion. He chose a spot in present day upper Austria on a lake now known as the Wolfgangsee in his honor, at the spot where an axe he threw landed. While traveling he took ill and reposed in the village of Pupping, in a chapel dedicated to St. Othmar (+c.759, the first abbot of the Abbey of St. Gall). His holy remains were brought back to Regensburg, and miracles were soon associated with them.

St. Conrad of Constance The last of this trio of holy bishops to be considered here is the great St. Conrad of Constance, who served his diocese, which spanned parts of southwestern Germany as well as portions of Switzerland and Austria, for many years in exceptional holiness that has ensured his continued veneration among the holy God-pleasers.

St. Conrad of Constance The last of this trio of holy bishops to be considered here is the great St. Conrad of Constance, who served his diocese, which spanned parts of southwestern Germany as well as portions of Switzerland and Austria, for many years in exceptional holiness that has ensured his continued veneration among the holy God-pleasers.

Like the other holy hierarchs discussed above, St. Conrad was similarly of noble lineage. Born around the year 900 near Weingarten in southern Germany, he was a scion of the noble Guelph (or Welf) family, from which many princes and other eminent and distinguished personages issued; accordingly, he was most excellently educated in the cathedral school of Constance. Despite the presumably golden prospects of worldly success that attended both his high birth and natural brilliance, though, he inclined from the very beginning to spiritual concerns and to the service of the holy Church.

Owing to his great aptitude and, still more, to his outstanding piety, evident from early youth, he rose quickly, being made bishop of Constance while still a young man in the year 934. In his humility, he was strongly disinclined to accept such a position, and much warm persuasion was needed to finally win his reluctant assent. St. Conrad had been championed especially by his close friend and confidant, St. Ulrich. And those fond hopes were not to be disappointed: For St. Conrad would hold this post for a remarkable forty years, until his repose in 975.

Upon assuming the bishopric the saint made an exchange of his inherited lands with his brother to get lands adjoining his diocese, which he then put entirely to the service of the Church and to charity for the local poor. He made pilgrimages on multiple occasions to both Rome and Jerusalem, and he adorned his home city of Constance with a number of new churches and monasteries modeled on the churches of those holy sites . These were financed largely from his private fortune, which he gave over entirely to the diocese. He filled these newly built churches with treasures and relics that he acquired from his pilgrimages. He was also active in the construction of hospitals, such as one he founded in Kreuzlingen; here he housed twelve indigents at his personal expense for the rest of their lives.

The bishop’s great holiness and immense spiritual, intellectual, and administrative gifts, made him a trusted advisor to Emperor Otto I. He was even present at the emperor’s coronation in Rome. However, the saint scrupulously avoided entanglement in worldly political affairs and in matters of state, having his mind firmly fixed on the eternal Kingdom. Owing to this fixity of purpose and closeness in spirit to heavenly realities, the saint was vouchsafed to witness something far grander than any earthly coronation: In Einsiedeln, Switzerland, he beheld Christ with various saints miraculously consecrate a chapel in that town.

Perhaps the most famous anecdote from St. Conrad’s lengthy and illustrious bishopric concerns an incident that happened one year as he was serving the Easter Mass. A large spider at some point fell into the Communion chalice. At that time and place, the belief was widespread that spiders were quite dangerous, even deadly. Yet, when the time came, St. Conrad did not hesitate to consume the gifts – spider and all! Whatever dread he may have had of the arachnid (which, again, given the times must have been considerable), his confidence in the all-protecting presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist dispelled any normal, human fears for his personal safety. Such courage and complete faith is admirable and inspiring. St. Conrad thus gives us an excellent—and timelessly relevant—example of undoubting faith in the power of communion and in the Savior’s eternal triumph over death.

St. Conrad reposed peacefully in the year 975. His relics were long venerated, beginning immediately upon his repose. Centuries later, during the horrors of the Reformation, his holy relics were thrown by vandals into Lake Constance. However, his head has been preserved to this day; it is kept in a special reliquary in the Cathedral in Constance, in a chapel that bears his name. St. Conrad’s nephew, St. Gebhard (+995), also later served for a time as bishop of Constance.

May the holy hierarchs Saints Ulrich, Wolfgang, and Conrad intercede for their lands and for all the Orthodox faithful. And may we all strive to imitate in some small way as best we can their holy examples.

A 20th Century New-Martyr

St. Alexander Schmorell of Munich (†1943)

This survey of the Orthodox history of the German lands concludes with a saint of quite recent times, the holy new-martyr St. Alexander (Schmorell) of Munich.

St. Alexander Schmorell of Munich Though he spent nearly his entire life in Germany, St. Alexander was of Russian birth, hailing from Orenburg, a city in southern Russia near the border with Kazakhstan. Though both his parents were Russian born, his father was ethnically German and confessionally Lutheran. However, young Alexander was baptized Orthodox and would remain unwaveringly faithful to the Church throughout his life.

St. Alexander Schmorell of Munich Though he spent nearly his entire life in Germany, St. Alexander was of Russian birth, hailing from Orenburg, a city in southern Russia near the border with Kazakhstan. Though both his parents were Russian born, his father was ethnically German and confessionally Lutheran. However, young Alexander was baptized Orthodox and would remain unwaveringly faithful to the Church throughout his life.

After the early death of St. Alexander’s mother and his father’s remarriage, the family relocated to Munich, Germany. Alexander was a very young child at the time. His Russian nanny, Feodosiya Lapschina, instilled deep Orthodox piety into him and kept him firmly planted in the Faith, even though his siblings and mother were Roman Catholic. As a student, St. Alexander once demonstrated his firmness of confession in a memorable way: In a religious class in school, in which he had been placed with the Catholic students, he was pressured by the teacher to make the sign of the cross in the Catholic manner, but he refused and would only sign himself in the correct, Orthodox way.

St. Alexander remained forever deeply attached to his Russian heritage, yet he also deeply imbibed German culture. He even once made a fine bust of his favorite composer, Beethoven. He was fond of horseback riding and fell in love with a girl. He was in many ways a normal, healthy young man with a typically youthful love for life.

The rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis, and especially the consolidation of their stranglehold over Germany, coincided with Alexander’s adolescence and cast a pall over him and his countrymen. As the abuses of the government became outrages, and the outrages became horrors, St. Alexander’s conscience could not permit him to remain silent. He would speak out, and he would ultimately pay for it with his life.

While a student at the University of Munich, where he studied medicine partly so that he would not have to engage in combat during his mandatory military service, St. Alexander helped form a student resistance group that called itself “The White Rose.” The group took its name from either a poem or a novel by that name (the group’s members, St. Alexander very much included, were of a strong literary bent); it was chosen as representing purity and innocence.

The White Rose published and distributed, in a necessarily limited fashion, a number of leaflets denouncing the Nazi government and its atrocities and calling on the German people to cast off the godless regime. This, of course was quite dangerous - literally a capital offense. St. Alexander personally authored the only known published denunciation of the Holocaust from that time period in Germany. He traveled to various cities in Austria distributing the group’s leaflets.

When certain key members of the group were captured by the authorities, the net began to tighten around St. Alexander. An attempted escape to Switzerland proved unsuccessful. He was captured when spotted in an air raid shelter, subjected to a show trial, and sentenced to death.

For nearly three months St. Alexander awaited execution at Stadelheim prison in Munich. During this time his faith, always strong, deepened considerably. He was as if already living in another, spiritual world. He wrote moving letters to his family, expressing his faith and stating his readiness to depart to eternal life. “Never forget God!” one of his letters memorably exhorts.

On the morning of July 13, 1943, St. Alexander received Holy Communion for the last time before being led to the guillotine in Stadelheim prison, where he received the crown of martyrdom and gave up his soul to God. He was 25 years old. In 2012, the Russian Orthodox Church numbered him among the saints as a martyr and passion-bearer. A church dedicated to the holy New Martyrs of Russia currently stands within sight of his grave in Munich.

There is an excellent recent book about St. Alexander’s life, published in 2017. It is titled Alexander Schmorell: Saint of the German Resistance. It was authored by Elena Perekrestov. The book gives an in-depth look at the saint’s life and discusses his times and the context and activities of The White Rose group. It is a gripping and moving read.

May St. Alexander of Munich, and all the holy Orthodox saints of the German lands, of whom there are so many over multiple centuries, pray for their lands, especially that these lands might return in large numbers to their true, Orthodox Christian heritage. Holy saints of the German lands, pray to God for us!