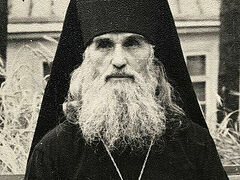

On September 6, His Eminence Metropolitan Veniamin (Zaritsky) of Orenburg and Saraktash reposed in the Lord. The author shares memories of His Eminence when he was still an archimandrite.

Metropolitan Veniamin In the spring of 1991, I got a call to my office. It was my good friend Valentina Alexandrovna Domnina (†2018), at that time a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR from Ulyanovsk.

Metropolitan Veniamin In the spring of 1991, I got a call to my office. It was my good friend Valentina Alexandrovna Domnina (†2018), at that time a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR from Ulyanovsk.

“Sergei, I’m in Ulyanovsk right now and I’m going to come see you. Okay? But I won’t be alone.”

A few hours later, the door swings open, and besides Valentina, I see in the doorway… a priest! A classic Russian priest, of heroic build, in monastic clothing, with a piercing gaze and long raven-black hair.

“Wow! If he weren’t a priest, I wouldn’t want to come across such a bull somewhere in a dark alley,” I thought.

To be honest, in those years, with the unheard-of revelry from organized gangs in Russia, as a large local entrepreneur, I was used to living under constant threats against my life from bandits—racketeers, thieves, and other smaller-time crooks. I was used to this psychological pressure. Therefore, the image of a mighty Russian peasant was automatically associated in my subconscious with this “glorious” crowd.

And, in fact, we entrepreneurs weren’t much different from them: We cheated everyone and everything, we dodged taxes, we impersonated others, we didn’t pay back debts. In a word, anything could happen…

Moreover, underneath my lovely expensive jacket a 9-mm Reck Agent revolver hung over my left shoulder. Unregistered, of course. What can you do? That was life…

And here in front of me stood a simple Russian priest-monk, in all his huge stature. His look was different, and his posture, and he had some kind of unusually affectionate speech, without any curse words at all… There were simply no such refined people in my world at that time.

“Can it really be,” I thought confusedly, staring point blank at Batiushka, “are there really people like this?”

It was a revelation for me. The contrast was striking.

***

Valentina Domnina, 1993 “Serezh,” Domnina started, “this is Fr. Veniamin—an archimandrite. We’re going to see Frolovich1 right now, and I decided to bring him to you. Batiushka is rebuilding a monastery. Maybe you can help him somehow?”

Valentina Domnina, 1993 “Serezh,” Domnina started, “this is Fr. Veniamin—an archimandrite. We’re going to see Frolovich1 right now, and I decided to bring him to you. Batiushka is rebuilding a monastery. Maybe you can help him somehow?”

“Sergei Vyacheslavovich,” the priest said, warmly entering the conversation, “His Holiness the Patriarch recently blessed me to work on rebuilding the old St. Nicholas-Ugresha male monastery2 near Moscow. It’s just on the other side of the beltway, in the city of Dzerzhinsk.

“His Holiness… Patriarch…,” I grumbled to myself sheepishly. “I don’t even know words like that. They’ve never been part of my lexicon. How to shoot down aerial targets, especially low-flying ones, that I know—they taught us at the institute. Or how not to return the money invested in my company to the shareholders, that I know too—I learned it on the fly. But about the Church? No, sorry, I don’t know anything…”

***

This whole conversation came about so unexpectedly that I was simply at a loss. I definitely didn’t expect that my friend, an ardent human rights activist and democrat, an assistant to Yeltsin himself, would collide with religion!

No, of course I was no longer a stubborn atheist by that time—sometimes, with a smart look on my face, I even liked to speculate abstractly about something sublime, “spiritual,” “about the meaning of life.” I would read random quotes from the Bible, the Koran, or some occult books in my free time. Thus, my poor head was a completely ecumenist mess at that time.

And I had a somewhat critical attitude towards the ROC-MP at that point—I, in all seriousness, condemned it for its alleged “fusion” with the state, calling it the “Ministry of Religious Affairs.”

But Fr. Veniamin continued:

“The monastery was practically destroyed, Sergei Vyacheslavovich. In Soviet times, it was home to a NKVD juvenile hall. Church life is only just now being revived. I’m not asking for anything exorbitant. But if it’s possible for you to help us, we would be very, very grateful.”

I thought about it. I had money. Not mine, of course, but the shareholders of the Simbirsk Commodity Exchange, which I had created and was in charge of at that point. Sometimes, when it came time to sign to authorize a payment, thinking about how huge the sum was, my fingers would sweat from fear and the pen would slip out of my hand. But it’s one thing to finance a concert at the Ulyanovsk recreation center, or distill a million dollars to our Ulyanovsk branch of Moscow State University for class furniture, or order a huge banquet in the best restaurant in the city, and it’s quite another to give something to the Church. Scary and incomprehensible…

In. short, I didn’t give him any money. I found some plausible reason and delicately declined.

But the archimandrite’s reaction was interesting. I refused him, gave him nothing, but how did he respond?

With a sincere, kind smile, with heartfelt warmth, with truly brotherly love, he pulled a healthy packet of books out of his bag and … handed it to me.

“Here, Sergei Vyacheslavovich, we’ve reprinted the best pre-revolutionary books on parenting at the monastery, and I wanted to give them to you. Please accept them!”

“Fr. Veniamin! I don’t even have a family yet—no children. And I don’t know if I ever will…”

But he gently insisted.

***

The door closed after my guests. They left. I sat for a long time, “digesting” this meeting, leafing through those wonderful books.

“The Spark of God: A Gift for Children, Archpriest Gregory Dyachenko,” I read on the cover of one of them. “Blessed for printing by the Moscow Spiritual Censorial Committee. Moscow, September 2, 1902.”

And what do you know? Six or seven years later, when my wife and I started having children, it was precisely these books that I used to raise them. Amazing!

***

Batiushka’s behavior towards Valentina Domnina herself and her family deserves attention.

I don’t know which of them found the other—whether she became a believer under Fr. Veniamin’s influence or if they met when she was already a believer, but in 1993, after GKChP-2, Batiushka helped her a lot. He even perhaps saved her life.

Then, after the bloody seizure of the Moscow White House, Domnina turned from an ardent supporter of Yeltsin into a fierce opponent in an instant. With her characteristic energy and fearlessness, she denounced her former hero for his atrocity wherever she could—in articles, at rallies, at pickets. It was then that a situation developed where there was a real threat to her life. And Domnina disappeared, without a trace, as though she simply vanished into thin air.

In reality, she spent all these months with her son at St. Nicholas-Ugresha Monastery, under the careful protection of Fr. Veniamin. And her son also began studying at the theological school that had just opened there. Now her son is a wonderful priest, serving in the Tver Diocese.

And in Ulyanovsk, Valentina behaved as an exemplary Christian. In the late 1990s, she even went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem together with our ruling hierarch, Archbishop Proclus (Kahzov, †2014).

***

Of course, that unexpected meeting with Fr. Veniamin in my office greatly contributed to my coming to faith. And when I went to Diveyevo for my first confession in 1996, I of course confessed this story, that I had refused to help the monastery, as a sin. It was a great painful burden on me then.

The well-known Elder Vlasy (Peregontsev) from St. Paphnuty of Borovsk Monastery (†2021), at whose feet I found myself in the summer of 1996, helped me with the correct spiritual understanding of this incident.

“Batiushka, why is everything so down in my business?” I asked, lamenting dejectedly in his cell. “All my firms—large, seemingly promising—one after the other have failed and closed.”

“Well, it’s because you didn’t pay your tithe to the Church from their profits.”

“??!”

***

Somewhere around 1998 or 1999, I found myself in Moscow on business. By that time, I’d long been involved in Church life, which I was incredibly happy about—I was printing the diocesan newspaper, I drove pilgrims around.

Then, traveling around the city, I wound up in the usual police roundup of migrants and unregistered newcomers—the bus was surrounded and passengers were released one at a time. Any suspicious people were put in the police van and in the confusion, I was thrown in there too.

They drove us to the police department on Volgograd Avenue and took us straight to a cell.

I found myself in quite picturesque surroundings in the slammer there: toothless grinning bums, clamoring gypsies, various Russian “guests of the capital” who had no traveling documents, hotshots from the Caucasus…

The police dealt with each one of us individually. I was saved by my long-standing nerdy habit of carefully keeping every piece of paper, because I still had my ticket showing how I had arrived in Moscow at the Kazan train station. Plus, I had my return ticket for the next day too. Therefore, I wasn’t overstaying the three-day grace period before I would have had to register my passport, and the stern, silent boss was very pleased—they apologized and let me go.

***

St. Nicholas-Ugresha Monastery

St. Nicholas-Ugresha Monastery

I went out onto the noisy avenue. It had already gotten dark while I was sitting behind bars. It was a windy evening—sleet was smacking me in the face, melting under my feet, and my shoes got soaked pretty quickly.

I was unbearably hungry. I reached into my bag, and as the wind beat upon me, I ate the last thing my wife had packed me for the road. But I had to find somewhere to spend the night…

Then, for some reason I remembered about St. Nicholas-Ugresha Monastery. Seven years had passed since that memorable encounter in Ulyanovsk, but for some reason I was sure that Fr. Veniamin would take me in. What made me so sure?

It took a long time, but with a number of transfers, I eventually made it to Dzerzhinsk, and there I was in the middle of the deserted nighttime square, standing before the tightly closed gates of the monastery. I knocked cautiously.

“Well!” I smiled bitterly. “It’s just like a scene from Cat’s House.3 I’m standing here, like a wet, skinned cat. It happens!”

They opened up to me, let me in, and so the dean of the monastery came to talk with me.

“Fr. Veniamin’s not here right now. He won’t be back till tomorrow morning.”

I explained who I was, where I was from, and asked to spend the night.

“Yes, of course. Come with me.”

We walked across the vast territory of the monastery in almost complete darkness. We carefully bypassed construction sites and their equipment. We passed the gates of the high bell tower. The monk carefully helped me so I wouldn’t stumble into some trench in the dark, and then said:

“Okay, I’ll put you here for tonight,” and opened the door to one of the buildings.

We went up to the second floor. It seems he had taken me to the guesthouse where bishops were received!

The dean opened one of the rooms for me, and I gasped—two rooms, clean, cozy, lovey curtains, a shower, mirrors, and expensive rugs everywhere! And slippers—soft and fluffy…

“Basically, just leave tomorrow whenever you want, and leave the key in the lock. May your guardian angel protect you. Good night.”

And Fr. Veniamin’s assistant left.

I couldn’t believe it myself!

“It happens like that,” I said to myself. “Just four hours ago I left the slammer, got soaked in the snow, and didn’t know where to spend the night, and now here I am, in bishops’ chambers!”

***

In the morning I decided I wanted to meet with Fr. Veniamin and thank him for his hospitality. I found him in the one-story abbot’s house next to the bell tower.

But he was already a little different—more restrained, more serious, and not so bold as before. Maybe he was just tired from the road? But, just as before, he was very kind and welcoming to everyone.

I thanked him for letting me stay the night and reminded him of our meeting in Ulyanovsk long ago. But he… didn’t recognize me. Or didn’t want to? Or was acting like he didn’t know me—he didn’t want to put me in an awkward position?

“Well, maybe it’s for the best,” I thought as I headed for the bus stop.

Just before reaching the stop, I looked back at the beautiful monastery—it was simply magnificent in the rays of the rising sun!

***

Over the coming years, I followed his episcopal career with interest—in Penza, in Ryazan, in Orenburg. I respected him very much and rejoiced in his growth. I put Vladyka’s name in my personal commemorations, and every day, my entire family prayed for him.

And now his earthly life has been cut off. Yes, it’s a little early by earthly standards. But apparently the Lord considered that Vladyka had completely fulfilled his earthly mission. There are no untimely deaths. It’s just we humans who think someone’s death is premature.

I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith (2 Tim. 4:7)—this is about him, a wonderful servant of the Church in our days, Vladyka Veniamin (Zaritsky).

1 Yuri Frolovich Goryachev, then the governor of the Ulyanovsk Province.

2 The name “Ugresha” comes from a tradition associated with St. Dmitry Donskoy, whom the monastery honors as its founder, in 1380. The tradition states that when St. Dmitry left Moscow to come out against the Tatar Mamai, he set up tents for his men to rest in a place overgrown with thick grass. There appeared to him an icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, beautifully adorned and surrounded by stars and illuminated by a bright light, floating in the air above a tree. The icon then descended into St. Dmitry’s hands, and arising in the morning, he said: “This has warmed (угреша, ugresha) my heart.”

3 A 1950s Soviet cartoon—Trans.