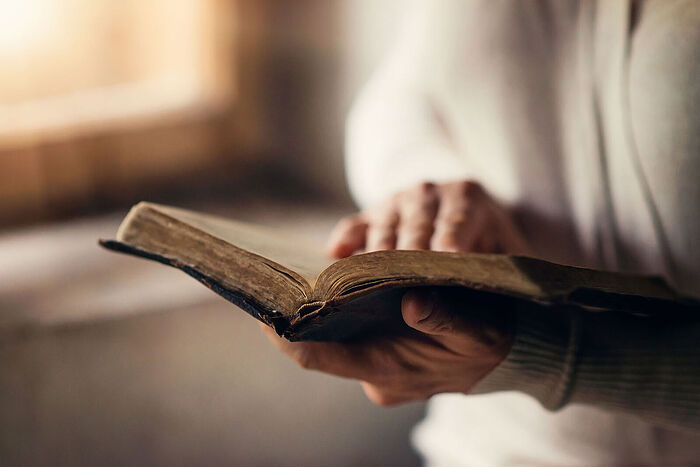

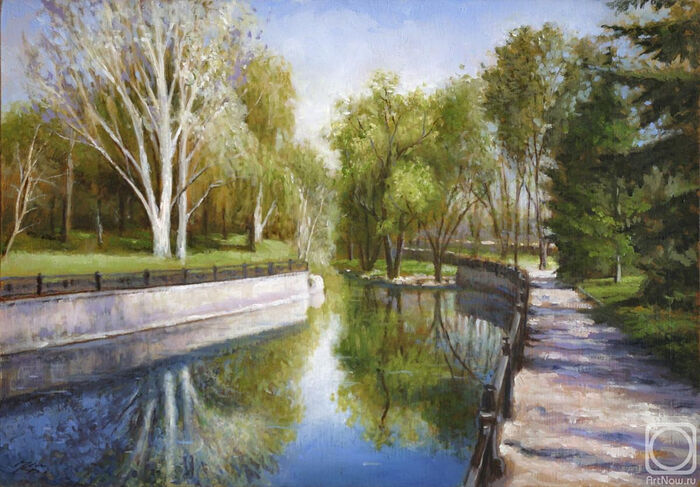

Simferopol. Salgir River Embankment. Spring. Artist: Vladimir Karlikanov

Simferopol. Salgir River Embankment. Spring. Artist: Vladimir Karlikanov

Simferopol. 1996. A warm, fine May day. I was walking along the right bank of the Salgir River towards the Cosmos cinema between the railway bridge and Gagarin Avenue. On the opposite side of the Embankment an elderly woman with a freshly planed plank on her shoulder was moving slowly towards me. The two-meter (6.5 feet) plank swayed with every step, and the woman had to hold it back. It was clearly uncomfortable for her to carry the plank on her frail shoulder, and she stopped to rest. Involuntarily I stopped too, noticing the woman’s face that had turned pink, and I saw her gray hair. Realizing that the woman was in her seventies, I said hello and offered my help:

“Let me help you carry your plank! It will be much easier together.”

The woman smiled warmly in response. Apparently, she did not expect me to start talking to a stranger across the river.

“The plank is light. It’s just uncomfortable to carry it,” she replied. “I’ll carry it myself. I live nearby,” she nodded towards private houses.

And suddenly she asked me:

“Do you believe in God?”

“Yes, I do!”

“I saw you wearing a headscarf,” she said and added with a special, solemn intonation in her voice:

“I knew Luke! Have you heard of him?”

“Of course! He has recently been canonized. Many people know about him now.”

“There was a time when everyone in Simferopol knew him. In the 1950s I worked as a nurse for Professor [she gave me his last name, which now, unfortunately, I can’t remember.—Auth.]... We had a difficult case. The professor could not cure the eczema of one important person. So my doctor turned to Vladyka for advice. And he took me to see him. Luke listened to my boss and dictated the recipe, which I wrote down. I remember that it included fresh homemade cream, honey or sugar—now I can’t say for sure—but something sweet, and medicinal herbs. I can’t remember which ones either. And earth—we processed it specially.”

I sighed, realizing that she was speaking about cataplasm, the recipe for which I had really wanted to find… The elderly woman continued:

“The professor immediately sent me to the market to buy cream and began to treat our patient with Voino-Yasenetsky’s prescription. I went to the patient’s home and applied ointment to his skin ulcer, as Vladyka taught me. Oh, you know! [The woman suddenly cheered up.—Auth.] I was very young then. And when I first got into the patient’s courtyard, I was greatly surprised because there was a real horse-drawn carriage in it! Can you imagine? However, it was no longer on wheels, but on supports.”

“Did the ointment help?” I steered the conversation in the direction that interested me.

“Of course! The skin ulcer healed quickly. The professor’s patient recovered. It was hard to believe that such a medicine could help. The remedy turned out to be miraculous!”

“But do let me help you carry it!” I again offered the woman to carry the plank together.

“No, thank you. You have a long way to go around the bridge, and I’m just a stone’s throw from my home,” the woman replied. She lifted the plank onto her shoulder and walked along the bank of the river that separated us.

Icons that renewed themselves

Today, many have heard a lot about miracles occurring in the Orthodox Church. Sometimes believers have themselves witnessed or experienced miracles wrought by the will of God.

Among the phenomena that haven’t yet been explained by science is the miraculous “renewal” of icons. I have often read or heard about such miraculous icons, on which layers of paint had been hidden from people’s eyes and then were suddenly miraculously revealed.

In the late 1990s I met a parishioner named Lydia Dmitrievna at the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs in Simferopol. At that time she worked at the library of the Crimean State Medical University [now the S. I. Georgievsky Medical Academy.—Trans.]. A highly educated specialist with good manners, and deep faith in her humble heart, Lydia Dmitrievna easily made friends, and we often talked with her on various topics after the Liturgy, especially about spiritual things.

One day Lydia Dmitrievna told me why she had come to the Church in an environment of total atheism, especially among young people. One day as a student she came to visit her aunt. Her aunt believed in God, attended church services and prayed at home in front of icons.

The woman gave her niece a small room. There was a bed in it, along with a bedside table in the corner opposite the bed. There was an icon on that ordinary bedside table, hiding part of the corner. The icon was dark, and it was impossible to see whose image was hidden under the brown layers.

Lydia Dmitrievna wondered why her aunt kept an icon in the house, on which nothing could be seen, but she didn’t want to upset her by asking.

One night Lydia Dmitrievna suddenly woke up, as if someone had awakened her. She lay for a while, and then looked in the direction of the dark icon. And at that moment, a light came from the icon with a push and the image lit up with a blue glow. After a while the radiance dissipated; but again, as if by some unknown power, the light came from the icon and surrounded it. It happened several times. The icon “pulsed” with light for a while.

Lydia could not understand what physical phenomenon she had witnessed, but gradually sleep won over, and the student fell asleep. In the morning the girl saw that an image of the Most Holy Theotokos with clear colors had appeared on the dark board. There was no trace of the brown left on the icon.

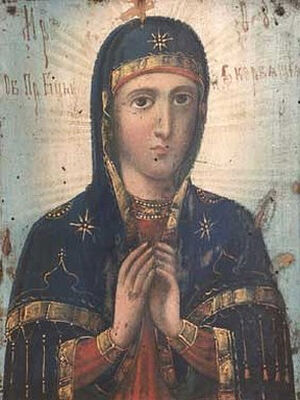

The “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God In 1998, all the faithful in the Crimea rejoiced at the miraculous “renewal” of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God. In August that year, in the village of Pervomayskoye of the Deanery of Stary Krym, Feodosia Denisenko, a parishioner of the Church of St. John the Baptist, donated to the parish a copy of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God. It was dark, with dull, faded colors. The priest placed the icon in the sanctuary so that its dark appearance would not confuse people. Services at that church were infrequent.

The “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God In 1998, all the faithful in the Crimea rejoiced at the miraculous “renewal” of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God. In August that year, in the village of Pervomayskoye of the Deanery of Stary Krym, Feodosia Denisenko, a parishioner of the Church of St. John the Baptist, donated to the parish a copy of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God. It was dark, with dull, faded colors. The priest placed the icon in the sanctuary so that its dark appearance would not confuse people. Services at that church were infrequent.

Two weeks later the priest noticed that the icon had begun to change—the colors had become lighter, and the dark spots had disappeared from the icon.

When the faithful learned about the “renewal” of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Queen of Heaven, they recalled that in Simferopol long before the 1917 Revolution there used to be a church on the territory of the military infirmary, dedicated to the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God. Apparently, this is why an image of the Mother of God with a mournful face and hands folded in prayer on Her breast was widespread in the Crimea. After the “renewal” of the icon, many believers felt that the appearance of this icon warned people about impending sorrows.

People complained that after the Church of the “Sorrowing” Icon was closed, it was used for many decades as a morgue. Currently, there is a small church in Simferopol in honor of the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God.

After the icon’s “renewal” the Church hierarchy established an annual feast of the “Sorrowing” Icon, which falls on November 6 according to the new calendar. With the blessing of Metropolitan Lazar of Simferopol and the Crimea, the wonderworking icon of the Mother of God was placed over the royal doors at the cathedral; then it was the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Simferopol, now it is the main church of the convent, in which the relics of St. Luke (Voino-Yasenetsky) rest.

Over the past twenty-five years, the “Sorrowing” Icon of the Mother of God from Simferopol has become widely known across the Orthodox world. On the territory of the convent, pilgrims are greeted by a mosaic image of the Most Holy Theotokos.

Priest Pavel Florensky called the icon a window into the Heavenly Kingdom, in which light always burns. Orthodox icons often become messengers of Heaven. And the faithful should not forget the Patristic teaching that the honor rendered to the icon confers to the Prototype.

From the life of Uncle Ivan

Memories tend to cling to one another. My mother’s younger half-brother Ivan Nikolaevich Belov (her father’s son) often comes back to me. He was tall, sedate and hardworking—just like his father and grandfather. He studied (as a part-time student) to become a forester in Lisino-Korpus near Leningrad and worked until his retirement in the forests near the city of Lyubotin in the Kharkov region, where he was born.

When he was young, at the end of every summer he would come to our house in Lyubotin with three stacks of books—he would bring school textbooks to his sister Galina, brother Victor and me. He was a man of great gentleness and compassion—I more than once saw tears in his eyes—but at the same time he was strong in spirit.

There was a wonderful story in Ivan’s life, which my mother told me, and then Ivan himself when we met. It was after the repose of his father—my grandfather—when Ivan was still single. Working as a forester, one morning he was walking briskly to his plot of woodland on the path he knew well that ran through the forest, then along the grassy slopes of hills. In a clearing Ivan saw a stranger—a gray-haired old man sitting by the path. Ivan greeted the old man and went on. But suddenly he called out his name:

“Ivan, sit down—let’s talk.”

“I’m hurrying to work, there’s no time,” my uncle tried to refuse.

“I know everything about you—you’ll get to work on time,” the stranger continued.

Ivan was surprised by such words, returned and sat down next to him. The old man was dressed in an old-fashioned way, with a canvas bag over his shoulder. He looked at Ivan affably and said:

“I want to give you a present.”

With these words the old man took out a large ancient book from his bag. It was without a cover and worn. He handed the book to Ivan. My uncle took it into his hands, opened it and saw that the book was written in old print with red letters.

“I can’t read in Slavonic,” Ivan confessed and held out the book to give it back to the old man.

“Try it,” the stranger said.

Ivan began to peer at its letters and read one word aloud, then the second one and became absorbed in reading. When he turned away, he looked around and didn’t see the old man. Ivan shouted, but no one answered him. So he went to work with the book.

It was in the USSR, and someone could get into trouble because of church books. So Ivan did not show it to anyone, reading it at home in the evenings when he was not expecting any guests. Early in the morning before going to work he would hide the book in the attic. He understood much of it, but some things didn’t come easiluy to him. For example, he struggled for a long time to understand the words: Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good (Rom. 21:12). When Ivan was telling this story to his mother, he even wrote down this saying to her on a small piece of paper that I would hold in my hands in those years.

“On the day that I finally puzzled out the meaning of those words, the book disappeared from my house. I turned the whole house over, trying to find the Book of Wisdom, but I never found it,” Ivan confessed to me.

Later, when State atheism was on the wane, Ivan became a parishioner of the church of Lyubotin and sang in the choir there. But couldn’t find any answers to the question of who that old man had been and where the mysterious Book had gone. It was most likely the liturgical Book of the Epistles.