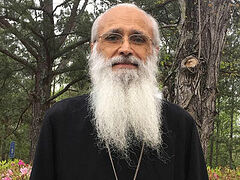

Hieromonk Silouan (Brown) is a typical American who attended a Protestant church from childhood, but then discovered Orthodoxy. He served in Iraq, which was a “real hell” for him. Upon his return, he wanted to commit suicide, but now he regards it as Divine providence. Perhaps without all this his path would have been different, and it would have been more difficult for him to set up an Orthodox mission in Africa and the Orthodox Africa nonprofit missionary organization, of which he is the executive director.

Fr. Silouan (Brown) with children in Kenya

Fr. Silouan (Brown) with children in Kenya

—Fr. Silouan, tell us about your journey to Orthodoxy.

—I grew up in a non-denominational Protestant church. Actually, I didn’t like it. Very early on I realized that when I went to church, I felt the same as if I had stayed at home to watch football. And football was certainly much more interesting. Church was a very low priority for me. However, in the early 1990s, a group of missionaries returned from Thailand. There was a popular legend then that AIDS could be cured by having sex with a virgin. So many Thai girls were sold into sexual slavery for basically nothing at all, for a bit of opium.

These missionaries were focused on ransoming these girls, sending them to school, and helping them live normal lives. It struck me, and I said to myself, “Okay, this is Christianity. This is something I can subscribe to.” I was thrilled by it.

When I was fourteen and fifteen, I was a Boy Scout, and my father found the book, Dancing Alone, by the famous author Frank Schaeffer, where he recounts how he converted to Orthodoxy. Then I started asking my father about it. There was an Orthodox church twenty miles away from where we lived in Colorado. My father asked our pastor about it a couple of times, but he said that the Orthodox were just some drunk Slavs on the wrong side of the tracks.

But when my father got Schaeffer’s book, he started asking more serious questions. In the end, we decided to visit the church, and so we ended up at Vigil. We immediately felt at home there, realizing that this is the true faith. After six or eight months our whole family was baptized. It happened on Holy Saturday, probably in 1996 or 1997. And we’ve been in the Church ever since, becoming more and more immersed in its life.

—And how did you, an ordinary American, find the Russian Church? Why did you decide to become a parishioner, and then even a monk?

—The parish we found belonged to the Orthodox Church in America, so I spent some time there. I served as a reader and studied at St. Tikhon’s Theological Seminary. From time to time, I had contacts with the Russian Church. And then I joined the Marines, fought in Iraq, and was seriously wounded. Then I heard about a hieromonk who was going to set up a monastery where veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and other similar war-related problems could get some help. Metropolitan Hilarion (Kapral), the ever-memorable First Hierarch of the Russian Church Outside Russia, blessed him to do it.

I thought it sounded like a wonderful thing, ideal for me, where my wounds could be healed and I could lead a monastic life. Unfortunately, the idea failed. Vladyka Hilarion withdrew his blessing and told me to leave. At that time, Metropolitan Jonah (Paffhausen), the ex-primate of the OCA, had just transferred to ROCOR and was going to set up a monastery. He told Vladyka Hilarion that he would accept me and I would become the first monk at his monastery.

Hieromonk Silouan (Brown) performs the sacrament of Baptism in Lake Victoria in Uganda

Hieromonk Silouan (Brown) performs the sacrament of Baptism in Lake Victoria in Uganda

—Did you really become the first monk at the Monastery of St. Demetrios of Thessaloniki, which was founded by Vladyka Jonah?

—Yes, I was the first to join Vladyka there.

—What does it feel like to be the first monk at a new monastery?

—The monastery was being established, so things went a little slowly. At that time, Vladyka Jonah still had contacts with the OCA. We were also serving at the St. John the Baptist’s ROCOR Cathedral in Washington. He was preparing to become the abbot of the new monastery, and he blessed me to finish my university education in Florida. There I was assigned to a church of the Moscow Patriarchate. When I returned to Washington, we still didn’t have a full-fledged liturgical cycle, which we have now. Therefore, I had some freedom, and I was blessed to develop the Orthodox mission in Africa and our Orthodox Africa organization, which I’m still in charge of. Thus, both my mission and monastic life really began to develop under the guidance of Vladyka Jonah.

As new monks joined us, we moved to another place, developing the monastic life. Now we have twelve brethren, and it’s wonderful to see how things have changed. We have a full-fledged monastery. I can say this is my shelter from the storm. This is the place where I can return after serving in Africa, recharge my batteries, and then do missionary work again.

There is very serious spiritual warfare in Africa. One of the bishops, who’s now reposed, said it’s hard for a monk to be a monk, a pastor outside the monastery, that they should return to their monastery at least once every six months, at least for a few weeks. St. Demetrios Monastery is this place for me.

—You served in Iraq, in Fallujah. Were you there in 2004 during the Phantom Fury operation?

—No, I didn’t participate in any known operations; I served in the military police. We carried out convoys in different parts of the country and served in the Ramadi-Fallujah corridor. It was in 2008.

—What was your experience like in Iraq? What did your military service teach you?

—Dissonance. We talked a lot about patriotism, about defending our country and stuff like that. To a certain extent, this was true. But I think many Marines, including myself, may have felt like mercenaries in a private military company. Although, of course, we served in the regular US Armed Forces. It was obvious that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. I’ve always had a clear picture of humanity, of those around me, and of different cultures, and I was never able to kill Iraqis as enemies of humanity. Whenever they shot at me, I thought: “The only difference between us is where we were born, nothing else. If I had been born with you, I’m sure I’d be shooting in this direction now too.”

All in all, it was simply dissonance.

—Did you see any miracles when you were serving in Iraq?

—I never saw a priest while I was there, so I had to email my Confessions to my spiritual father in Colorado. After getting my message, he’d go to church, put on his stole, and read the prayer of absolution. There was a ten-hour time difference between us. The middle of the day for him was the middle of the night for me, but whenever he read the prayer of absolution, I always felt it, no matter what I was doing or what stressful situation I might have been in. I always felt it when he read the prayer of absolution. For me it was a real connection with the Sacrament of Confession. That’s the main miracle that I remember.

—Did you feel it even during combat operations?

—Yes, I did. Bullets would be flying around me, but I knew my spiritual father was reading the prayer of absolution.

—Did you feel God’s presence on the battlefield? Does He reveal Himself to those in danger?

—That’s what I just told you about with long-distance Confession. And before doing anything I would always think: “What will I say at Confession? How will I tell this to Christ?”

—Many people in Russia believe that the United States waged an unjust war against Iraq. What can you say as someone who was there and saw everything with your own eyes?

—Yes, this is exactly what I said about feeling like a mercenary of a private military company and working for some oil corporation or something like that, and getting paid for it. I don’t want to go deep into politics—I’m no expert—but, in my opinion, it’s pretty obvious now that the people we killed didn’t actually pose any real threat to Americans. I don’t think we were ensuring America’s security with the war.

—Had you been ordained before your service in Iraq?

—I was tonsured a reader when I was seventeen. So I was already a reader in Iraq. I was twenty-three or twenty-four then.

—Can you say that serving Iraq opened your eyes to something important in Orthodoxy?

—Not so much my service there as spiritual therapy and rehabilitation. I was an absolute wreck when I got back from Iraq. I still feel the wounds that I got there. I had suicidal thoughts. I would lock myself up in my room for hours with a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a gun pointed at my forehead in the other. I just wanted to die.

Communion with Christ, which the Orthodox Church offers us, and spiritual therapy help truly heal all our wounds. In my case, they appeared on the battlefield, but situations vary. People healed through the spiritual life, the transformation of an empty and lost young man who wanted to die into a hieromonk, and the healing that Christ grants us through faith is a true testimony of what the Orthodox Church gives us.

—Maybe it was a miracle in itself that God helped you make it through all the trials?

—When I wanted to commit suicide, my gun was loaded. And there was no reason not to shoot. So, yes, it was a miracle.

—Now you’re a hieromonk and a veteran with battlefield experience. What do you tell your spiritual children about how to avoid wars? Not only external, but also internal ones, which is perhaps much more important.

—Maybe this isn’t totally a soldier’s answer, but I don’t preach avoidance. For example, Iraq as hell for me, but because of it I started getting a medical pension. This helped me start missionary work in Africa, because in the first three years I paid for everything there myself. We had very few donors back then. I see Divine providence—the Lord has arranged everything so that I can live in His providence. And I believe He can lead us out of a dead-end into something better.

You could say the reality we face in Africa is extreme. But after Iraq, after serving in the Marines, it’s not shocking for me. I was there, and the Lord has used everything, every part of my life so that I could serve now.

So I wouldn’t preach avoidance.

I preach self-denial in order to truly surrender to Christ with everything we have. And to trust Him, to believe that He will do everything for the best—maybe not in this life, but, undoubtedly, in the life to come. It’s important to simply trust in His providence that whatever we’re going through now, no matter how hard it may be, it’s all for a reason and serves for our salvation. I think that’s all we can do. We have no control over other people; we find ourselves in situations we don’t like. We’re imperfect people who are trying to renew an imperfect world.