Post-mortem portrait of Eudoxia Lukianovna Streshneva from the Petrine era. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org The old merchant town of Meshchovsk, Kaluga Province, gave Russia two tsarinas, Eudoxia Lukyanovna Streshneva, wife of Mikhail Fyodorovich, the first monarch of the Romanov dynasty (1596–1645), and Eudoxia Fyodorovna Lopukhina (1669–1731), the first wife of Tsar Peter the Great.

Post-mortem portrait of Eudoxia Lukianovna Streshneva from the Petrine era. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org The old merchant town of Meshchovsk, Kaluga Province, gave Russia two tsarinas, Eudoxia Lukyanovna Streshneva, wife of Mikhail Fyodorovich, the first monarch of the Romanov dynasty (1596–1645), and Eudoxia Fyodorovna Lopukhina (1669–1731), the first wife of Tsar Peter the Great.

Eudoxia Lukyanovna was born in 1608 into the family of an impoverished nobleman Lukyan Stepanovich Streshnev. Her mother, Anna Konstantinovna (1584–1650), bore her husband five children, and Eudoxia was the middle child. Since her parents were poor, they sent her to live under the care of the family of okolnichy1 Gregory Volkonsky, a rich relative on her maternal side. In her new family, the gentle and virtuous Eudoxia received insults from the bad-mannered boyar’s daughter who was of the same age as her. She never complained to anyone, but instead silently endured all the offenses. Eudoxia’s childhood years were during the Time of Troubles, one of the most terrible and calamitous times in Russian history. It ended with the accession of seventeen-year-old Mikhail Romanov, who was elected to the throne by the Zemsky Sobor [People’s Council] on February 21 (March 3), 1613.

When Mikhail was twenty years old, his mother, Nun Martha, decided to marry him off. When the candidate brides were shown to the tsar, he chose Maria Khlopova, the daughter of a Kolomna nobleman. But the girl suddenly fell seriously ill, and Nun Martha declared that the bride wasn’t suitable for the role of tsarina. Maria and her family were sent into exile in Tobolsk. Then, Princess Maria Dolgorukova was declared the sovereign’s bride and Tsar Mikhail married her on September 18, 1624. But on the very next day following the wedding, the tsarina fell ill with symptoms of poisoning. She died after severe illness that lasted for three and a half months.

In order to strengthen the Romanov dynasty, the tsar had to leave an heir and thus save the country from a new Time of Troubles. Therefore, in 1626, Mikhail Romanov decided to get married again. The choice of brides was held in full accordance with the old Byzantine tradition: Sixty girls from the most distinguished families, “of inherent stature, beauty and intelligence,” arrived to Moscow to be shown to the Tsar. But Tsar Mikhail did not like any of them. He decided on the eighteen-year-old Eudoxia Streshneva, who wasn’t among the girls chosen for the viewing, but rather had come to the palace as handmaid to the daughter of Grigory Volkonsky. His family was displeased that their son chose the “lowborn” Eudoxia, but Mikhail remained adamant. Neither his mother’s displeasure, nor the boyars’ resentment that their own daughters were rejected, could deter him. The monarch declared that she was a girl according to his heart, and what’s more, he saw it as his Christian duty to help her to leave the house of her oppressive relatives. His parents had to submit to his will.

On January 29, Mikhail Fedorovich officially announced his marriage to Eudoxia Streshneva. In order to prevent enemies from “dispatching” the bride, Eudoxia was brought into the Kremlin chambers and named tsarevna only three days before the wedding. The tsar’s messengers travelled to Meshchovsk to Lukyan Stepanovich, the father of the sovereign's chosen one, so that he could bless his daughter for the marriage.

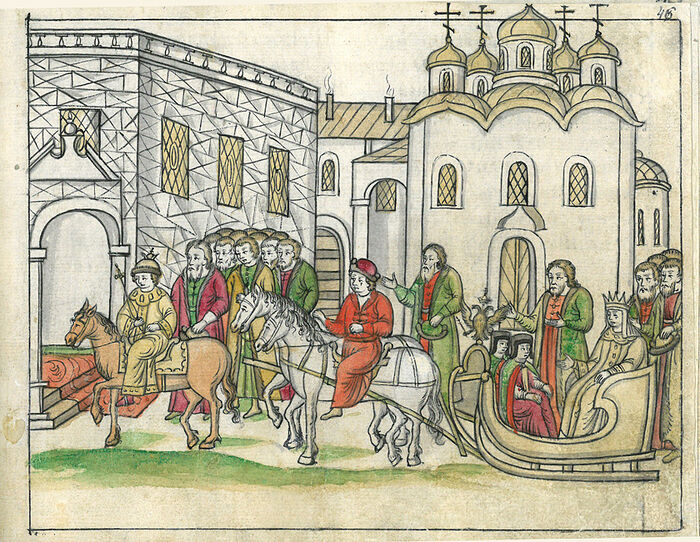

Wedding cortege of the tsar in Kremlin. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org

Wedding cortege of the tsar in Kremlin. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org

Lukyan Stepanovich Streshnev (who died in 1650) was very poor. He tilled his small plot of land with his own hands. A shabby hut with a thatched roof burst into view to the arriving messengers of the tsar. The owner was dressed in a caftan of homespun brown cloth. When he was told his daughter had been named the royal bride, he knelt before the icon and tearfully exclaimed: “Almighty God! Support me with Thy right hand, that I don’t fall victim to corruption in the midst of honors and riches!” Later on, when he was the sovereign’s father-in-law, Lukyan Stepanovich was known for his modesty, hard work and generosity. His daughter inherited his qualities.

The solemn marriage ceremony of Mikhail and Eudoxia Romanov was held on February 5, 1626. Patriarch Philaret, Mikhail Fedorovich’s father, officiated at the service and blessed the Tsar and his bride with the Korsun Icon of the Mother of God. Thus the Russian Cinderella found herself on the throne. Those close to the court gossiped with concealed envy about the new tsarina, saying that “she’s not a high-priced tsarina”, since it hasn’t been long since she wore “yellowish boots”, meaning the cheapest boots. The highly-placed boyars kept gossiping about Eudoxia’s “humble” origins for many years.

Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org Historical evidence is unanimous in calling the Tsar's second marriage a happy one: Mikhail Fedorovich and Eudoxia Lukyanovna lived in love and harmony for nineteen years. The spouses were united, above all, by their fervent faith in God—the guarantee of their family happiness.

Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich. Illustration: ru.wikipedia.org Historical evidence is unanimous in calling the Tsar's second marriage a happy one: Mikhail Fedorovich and Eudoxia Lukyanovna lived in love and harmony for nineteen years. The spouses were united, above all, by their fervent faith in God—the guarantee of their family happiness.

The main job of the young tsarina was childbearing. To everyone’s disappointment, Tsarina Eudoxia’s first and second pregnancies resulted in the birth of daughters, and not the desired son, heir to the throne. The queen prayed earnestly that the Lord send her a son, and often went on pilgrimage to holy places and monasteries, generously donating rich gifts. Her prayers were heard, and on March 17, 1629, to the great joy of his parents, relatives and all the Russian people, son Alexei, heir and the future Tsar of Russia (1629–1676) was born to the Romanovs. In the acts of that time, this event was called none other than “the universal joy of the sovereign.” Out of all ten royal children born to Eudoxia only four lived to adulthood: Irina (1627–1679), Alexei (1629–1676), Anna (1630–1692) and Tatiana (1636–1706). Difficult times fell to the lot of the royal family in 1639, when one after another they lost the five-year-old Tsarevich Ivan and the newborn Tsarevich Vasily. Tsarina Eudoxia, although she took the death of her children very hard, still bore her sorrows with patience and humility. Following the death of each child, she would generously offer monetary donations to churches and to the poor for the repose of his soul.

The family life of the first Romanovs was based on strict piety

The family life of the first Romanovs was based on strict piety, daily observance of the prayer rule, the reading the Holy Scriptures, and attending church. Annually, on the day of the memory of St. Sergius of Radonezh, the tsar and tsarina would make pilgrimages to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery. Sometimes Tsarina Eudoxia would go on pilgrimages to the miracle-working “Revealed” icon of St. Nicholas the God-Pleaser on Arbat Street. In 1634, she sent a letter to Novgorod to her former father confessor, Archpriest Maxim, asking him to inform her about all the miracle-workers of Novgorod. The Tsarina followed the established customs and rites. For example, if on the feast of St. John the Baptist the Tsar immersed himself in the “Jordan” on the Moscow River, the Tsarina would in turn take a dip at the pond in the village of Rubtsovo, a favorite summer vacation spot of the royal family. The couple greatly revered Venerable Alexander Svirsky, whose relics were uncovered in 1641. In 1643, the Tsar arranged a rich silver reliquary for him, while the tsarina hand-embroidered the gold and silver cover for his relics.

The upbringing of the children in the royal family was imbued with the Gospel spirit. Following the birth of a tsarevitch or a tsarevna, Eudoxia Lukyanovna would order an icon of the patron saint to be painted for each of her children. She taught her children to pray diligently and often took them to church services for Communion—not only in the court churches, but also the parish churches. On the children’s Name Days, she generously gave alms to the poor. When her children were sick, she prayed diligently, ordering prayer services for their health in monasteries and churches of Moscow and other towns, asking to bring to her household the miracle-working icons from Moscow churches to serve molebens before them. She always gave alms for their health.

As was customary in those times, Tsarina Eudoxia led a secluded life in the intimate circle of her family, close boyar women and handmaids. The people never saw the tsarina and royal children—trips were made only in closed carriages, and the Tsarina and princesses would have their faces covered with expensive cloths of dense texture. After saying the morning prayer rule in her room, the sovereign would usually attend Liturgy in one of the house churches. Before dinner, Tsarina Eudoxia would do needlework; she embroidered vestments for her house churches, for other cathedrals and monasteries, as well as clothing for her husband and children. Inside her living quarters, skillful craftswomen, closely supervised by the Tsarina, embroidered, and made linen and even children’s toys.

Eudoxia avoided state life, remaining far from the intrigues and struggles of warring parties at court. She served her country entrusted to her by God through the Tsar, to whom Eudokia was a faithful assistant and friend in everything. It is not without reason that even at his betrothal, the tsar told his bride that the Lord has chosen in her the mother of the Russian people.

Eudoxia Lukyanovna was heavily involved in performing deeds of mercy. Numerous widows and orphans submitted petitions to the Tsarina through a scribe, asking for help in distress. Having read their petitions, the kind Tsarina Eudoxia tried to fulfill their requests, for having suffered herself, she understood the plight of others. She dictated to the scribe and he made notes who the recipient would be and how great an assistance they should receive. She interceded before her husband the Tsar for the wrongfully convicted, often saving them from imminent death. On church feasts, alms were distributed on behalf of the Tsarina at churches and she would also send alms to prisons on great Church feasts. In her palaces, the Tsarina had arranged living quarters for orphaned girls, and she took the most active part in their fate. When they were sufficiently grown, she would give them in marriage to good house serfs, whom the Tsarina had previously reviewed and approved. She made a sizable donation to the restoration of the Meshchovsky St. George’s monastery, where her ancestors were buried in the necropolis. Up until the end of her life, Eudoxia never ceased doing good deeds for her subjects.

On festive days, time was dedicated to various fun activities. Balalaika players, jesters, wandering actors, and dwarfs performed before the members of the royal family in the Toy Chamber. Blind singers sang folk tales, folk poems and spiritual songs to the sound of the domra.2

Every year on March 1, Tsarina Eudoxia’s birthday was solemnly celebrated in the Golden Chamber. The Tsar, showing great care for his wife, would present to her diamond and gold jewelry both on her birthday and after the birth of each child. In the days of the annual major feasts, Tsarina Eudoxia organized festive receptions in the Golden Chamber, when the boyar women and royal relatives would come to the palace. According to the ancient custom, a festive dinner was arranged for the guests. Elderly nuns from the three Moscow the Ascension, Novodevichy and St. Alexis Monasteries, were also invited to join them at the table.

The first royal Romanov couple’s final years were far from serene. Tsarina Eudoxia fell seriously ill. A case was brought against the court craftswomen who admitted (perhaps under torture) that they attempted to “put a hex on the Tsarina” through witchcraft or even to poison her. Apparently, the fact of poisoning did take place, as modern studies of her remains showed the presence of lead, arsenic and mercury in her bones in quantities many times exceeding the maximum allowable concentration.

Historical chronicles testify about the piety of Tsarina Eudoxia, as well as her modesty, intelligence, and physical beauty. Not only her husband and children loved her, but also the people honored her, and subsequent generations have preserved a good memory of her.

Royal authority was a “crown of thorns” for Mikhail Fedorovich. During his reign, the worst consequences of the Time of Troubles were overcome: He restored the economy and trade in the country and ended wars with Sweden and Poland. He reformed the army. Russia grew to add lands along the Yaik River, Zabaikalye, and Yakutia and gained access to the Pacific Ocean. A reasonable system of taxation was developed and the political power of the country was improved, among other things. But, most importantly, the Tsar defended the independence of his country.

All these tasks were within the tsar’s power with the support of God, family members and, of course, his wife Eudoxia Lukyanovna—a faithful, affectionate and loving assistant to her husband.

Pining for her deceased husband, the inconsolable tsarina-widow died at the age of thirty-seven, five weeks after the death of her beloved husband

Mikhail Fedorovich died on July 23, 1645, passing the throne to his son Alexei Mikhailovich. Pining for her dead husband, the inconsolable widowed Tsarina spent her days and nights in tears, grief and prayer, and passed away at the age of thirty-seven, five weeks after the death of her beloved husband. She was buried in the family vault for royal women in the Resurrection Monastery in the Kremlin. In the present time her tomb-chest is kept in the basement chamber of the Archangels Cathedral in the Kremlin.

In spring of 2011, a grandiose monument to Eudoxia Lukyanovna, the matriarch of the crown-bearing Romanov dynasty, was opened on the territory of Meshchovsky St. George Monastery.