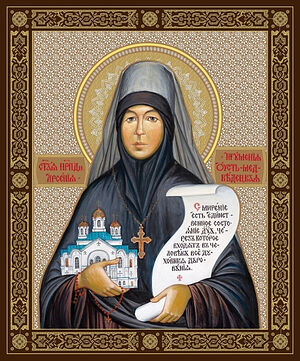

Photo: volgeparhia.ru On October 21, 2016, the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church canonized St. Arsenia of Ust-Medvedits as a locally venerated saint of the Volgograd Metropolis.

Photo: volgeparhia.ru On October 21, 2016, the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church canonized St. Arsenia of Ust-Medvedits as a locally venerated saint of the Volgograd Metropolis.

Abbess Arsenia (1833-1905) came from a notable family of the Don region. At the age of seventeen, Anna Mikhailova entered the Ust-Medvedits Monastery of her own accord. The monastery reached its highest peak in the 40 years of her abbacy, from 1864 until her repose on August 3, 1905.

Besides her educational and charitable activities, the main fruits of Venerable Arsenia’s labors were the Kazan Cathedral, which was erected from 1785 to 1885, and the famous caves, dug in the image of the Kiev Caves. Today the monastery’s main shrine is there—the miraculous stone slab with hand and knee imprints of people kneeling in prayer, where the faithful come to beseech St. Arsenia for healings, the good arrangement of worldly affairs, and prosperous family lives.

In addition to her holy life, St. Arsenia left us valuable writings on the spiritual life, which we present in honor of the anniversary of her canonization.

***

In 1833, a daughter was born to the Sebryakovs—a family of well-known landowners in the Don Province. She was baptized with the name Anna. Her parents had a special love for her because she was an unusually kind, joyful, and intelligent girl. The amazing purity of heart that God gave Anna from birth was preserved in her until the end of her life, and therefore the path of her life was clear and straight.

The spiritual gifts of little Anna were noticed by Archbishop Anthony (Smirnitsky) of Voronezh, who was revered by many for his kind life and clairvoyance. Anna was not yet three years old when her parents took her to Voronezh to visit the archbishop, whom they had known for a long time. As soon as the girl saw the elder, she broke away from her nurse’s arms, ran up to him, and prostrated before him. He blessed her and told her surprised parents: “She will be a great woman.”

These words proved prophetic: Abbess Arsenia was truly great in her spiritual life.

When Anna was six, her mother died. After the death of his beloved wife, her father, Mikhail Vasilievich, refused secular pleasures and never left the Sebrovo estate. He was very intelligent, very educated, and most importantly—he was a deeply believing Christian. He spoke with his children a great deal and passed on his best qualities to them. He often read the Gospel and the lives of the saints to the children, and would then explain what he had read in an accessible way. These readings and talks sunk deep into the soul of little Anna. “I was so amazed as a child,” she later said, “by the wondrous, high teaching of the Savior, and the thought that we don’t fulfill His holy commandments deeply disturbed my soul.”

“Why don’t we do what the Lord commands?” she asked the sisters. “Why don’t we give everything away and follow Him?” These questions were the most important thing for her, but even her own sisters couldn’t understand her. However, Anna didn’t withdraw into herself, but remained friendly, compassionate, and very open. She was very sensitive to all the good in the people around her, and was able to support, gladden, and bring people out of despondency, and unwittingly instilled in her loved ones the joyful outlook on life that was characteristic of her from early childhood.

At the same time, realizing that even loved ones couldn’t answer her most important questions, Anna intensified her prayers to God, asking Him to show her the meaning and purpose of her whole life. And the answer came in the words of the Lord Jesus Christ, long familiar to her: I am the way, the truth, and the life (Jn. 14:6), which opened up in a new way, sounding forth like a revelation: The meaning of life, and peace, and the happiness of man are in God, in following Him, in acquiring those qualities of soul that unite a man with Him.

Anna was just fourteen years old when she came to understand this. She passed through this difficult age, as they say now, when young souls experience the heaviest temptations and stray from the path of truth, having confirmed herself in faith and having preserved the purity of her thoughts. Remaining cheerful and friendly with everyone, she increased her prayer and began to read spiritual literature more, especially the Gospel, which she often hid under the cover of a secular book so as not to draw attention to herself. Thus, without even thinking about monasticism, she was already essentially following that monastic path that prefers hidden, inner work to visible asceticism. Several years went by, the thought of monasticism grew up and matured within her, and Anna decided to speak with her father about it. Mikhail Vasilievich blessed his beloved daughter, and on December 30, 1850, took her to the poor Ust-Medvedits Monastery, when Anna was seventeen.

Igumena Virsavia, abbess of the monastery, was happy to receive Anna; the name of Mikhail Vasilievich Sebryakov was known throughout the Don Province, and for the abbess, it was a great honor to receive his daughter into the monastery.

In the monastery, Anna took no notice of the poverty, was not afraid of the simple fare or the seeming severity of the nuns, realizing that they were to become her sisters in Christ. And this good disposition of her soul couldn’t but arouse sympathy in the hearts of the guileless nuns! Anna bore the most difficult obediences with them: She helped roll out the dough and bake prosphora, she went around at night to rouse the nuns for midnight prayer, she served meals in the trapeza, and washed the floors—and all this on par with ordinary girls, trying to imitate them in everything.

She didn’t disdain any menial labor, including chopping wood, stoking stoves, washing dishes, and cleaning cauldrons. She always slept in her cassock and a leather belt and dressed very simply. When not working, she spent her time in prayer and reading spiritual books. Reading the works of the Holy Fathers, she sought to experience and assimilate their rules. Trying to always keep the Jesus Prayer in her mind, she habituated herself to silence, making it a rule not to say anything superfluous.

However, in general, her life in Ust-Medvedits Monastery didn’t develop at all as she had hoped. It was impossible to wholly leave the world and its glory there: Everyone knew and revered her, and this disturbed her inner peace of soul. The things the abbess was concerned about began to weigh on Anna. She saw a difference in their spiritual orientations: The severe, purely external asceticism of Abbess Visaria, not filled with an inner search for the Living God, seemed almost pointless to her. Anna started looking for a spiritual guide from amongst the nuns, but those with whom she tried to find a common path were inexperienced in spiritual matters. They hoped more in external asceticism in the work of their salvation, giving little attention to the purification of their hearts. Anna sought a mentor for six long years. During this time, she was tonsured as a nun with the name Arsenia (1859). Finally, she turned to Schemanun Ardaliona, whose simplicity, sometimes bordering on rudeness, previously prevented her from seeing her spiritual depth.

When Mother Arsenia began to turn to the schemanun with various questions about her thoughts, her answers convinced her that she had a deep understanding of the spiritual life. Arsenia was amazed by her clear determination of the states of the human soul and her concept of prayer. Schemanun Ardaliona soon became Nun Arsenia’s spiritual guide, and she went under full obedience to her, completely cutting off her personal will. Her guide led her so strictly along the monastic path that, viewed from the outside, it could seem that she was rude and unjust with her spiritual daughter.

For example, wanting to wean Arsenia from any, even insignificant earthly attachment, the schemanun once cut up an embroidered rug that Arsenia especially treasured. Arsenia endured this seemingly cruel act with complete humility and obedience, seeing in it only her mentor’s concern for the salvation of her soul.

Another time, Arsenia gave a beggar a fifty-kopeck piece (a considerable sum for that time). The schemanun, seeing that with such generous alms she seemed to elevate herself above others, and fearing that vanity would thereby arise in her soul, angrily reproached her and sent her to find the beggar and take back the money.

There were many other instances of strict spiritual guidance from one side and deep humility and obedience from the other.

Thus, Arsenia spent five years in labors, prayer, and complete obedience to the eldress. Later, when she became abbess, she would tell the nuns about that period: “I consider those years the best in my life.”

And she spoke about the guidance from her mentor:

The activity of even the most subtle passions couldn’t hide from Mother’s clairvoyant gaze. Pointing to these passions living in the heart, she would give her interlocutors advice for her to get out of the passions, to attain purity of heart, which is all the Lord is looking for from us. With a word, like a sword, she worked on the soul of her neighbor, cutting off its impurity; and she acted in deed, sometimes putting you in a position where you either had to renounce your self-love or some other passion, or lose your spiritual guide…

Not attaching any special importance to external asceticism, the schemanun would say: “The main goal of your search should be the virtues. And in order to acquire them, you have to uproot the passions and all carnal impurity. It’s not easy…”

Much later, in old age, recalling this, Mother Arsenia told one of her close disciples:

The path of the battle against the passions is the most difficult path. It is indicated by Jesus Christ, and He calls it narrow and sorrowful. Another, easier path, which many people take, is life according to the passions. You see that many sisters don’t even know about the existence of another path beside the one they’re on. They go to church, read the familiar rule, make a certain number of prostrations, and they’re convinced they’ve fulfilled everything. They don’t undertake to work on the inner man; they don’t seek, they don’t try to annihilate the passions at the root.

After the repose of Abbess Virsavia in 1863, almost all the sisters asked Mother Arsenia to accept leadership over the monastery. Arsenia agreed only out of obedience to the schemanun, and at the age of thirty, she was consecrated as abbess. She bore this cross in her native monastery for more than forty years, until her own repose.

Having become the abbess, Igumena Arsenia became the mother for all the nuns, experiencing all their sorrows in her heart as her own. Her love for neighbor, that is, for anyone who turned to her for help and advice, was obvious to everyone. This love was inseparable in her from love for God, which visibly shone in her eyes. The nuns recalled that sometimes Mother was so inspired in spiritual conversation that her face changed and it was impossible to listen to her without a particular inner excitement.

Having become the abbess, Igumena Arsenia became the mother for all the nuns, experiencing all their sorrows in her heart as her own. Her love for neighbor, that is, for anyone who turned to her for help and advice, was obvious to everyone. This love was inseparable in her from love for God, which visibly shone in her eyes. The nuns recalled that sometimes Mother was so inspired in spiritual conversation that her face changed and it was impossible to listen to her without a particular inner excitement.

Under Abbess Arsenia, the monastery was transformed. She first dealt with the library, realizing the exceptional importance of the writings of the Holy Fathers for learning humility, repentance, and for correctly seeing one’s soul with all its passions, unexpectedly revealed to the attentive eye. In 1867, Matushka managed to open a girl’s school in the monastery. At first, young novices studied there, who later became teachers themselves. Abbess Arsenia and the priests of the monastery also taught there.

According to Abbess Arsenia’s design, the Kazan Cathedral was built with the lower church of St. Arsenios the Great (1875–1885). A two-story building was built for the nuns, a house for the clergy, outbuildings were renovated, but her work didn’t stop there. Over the course of the last fifteen years of her life (1890–1905), Abbess Arsenia built a monastery dependency in the village of Uryupinsk. Under her leadership, the old Holy Transfiguration Church was renovated, and a side chapel in honor of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God and St. Seraphim of Sarov was appended to it. The abbess also founded a skete on her sister’s estate.

How Mother managed to combine her inner spiritual life, preaching, and works of love with the active management of the monastery remains a mystery of her talent. One thing is clear: She was chosen by God, and her whole life justified the words of the elder who once said of little Anna: “She will be a great woman.”

Mother Arsenia, very demanding with herself, was condescending to the infirmities and vices of others and tried not to condemn anyone, but only deeply grieved for those who stumbled and made haste to give a helping hand. She generously shared wise advice, was able to calm the grieving, and found a word of comfort not only for the sisters, but also for laypeople who turned to her for spiritual help, who shared their troubles with her as with their own mother.

It sometimes happened that Mother Arsenia spent the entire day with visitors and managed to retire to prayer only late in the evening. The sisters noticed that she became even more open, that some special humility and meekness was manifested in how she dealt with others. “Was our Mother like this before?” they said in the monastery, recalling how their abbess used to be: young, full of life, and sometimes strict, not accessible to everyone. “She’s getting weak, apparently. She walks with strength, and it seems she’s ready to accept everyone, to talk with everyone.”

Here are examples of Mother’s spiritual discernment preserved in her letters and diaries:

If you were at war, could you say you don’t want to go fight? No, you would go, without thinking, to an obvious death. If there’s a spiritual battle ahead, if God’s commandments demand a struggle, how can we say we don’t want to fight, that it would be better to give ourselves captive to our enemies? What a disgrace!...

Salvation is possible in every place and in every affair; it need not be sought outside of us; everything can be found in our souls—both Heaven and Hell. If we find Hell in it, then by the grace of God, laboring over ourselves, we can also find Heaven…

We don’t even know what’s good for us and what’s bad. But we can see God’s help, His mercy for us, in that He allows us to bear the unbearable with patience, with humility, with submission to His holy will…

Don’t jest with your feelings; they, like a fire, can destroy everything in the soul, and in the heart, and in the mind: What the word of God has planted, they will burn and leave the soul with only its passions and sins. We have to preserve purity of body and soul, otherwise the soul will die…

In the last years of her life, Mother paid absolutely no attention to her infirmities and ailments and didn’t take any care for herself at all.

She was ill the entire winter of 1904–1905. Sensing her imminent departure, she instructed the nuns: “You have to get used to the thought that I won’t be with you, and learn to live without your mother.”

In the summer, she went to Sarov to venerate the relics of St. Seraphim. It was a difficult journey; she was seriously ill along the way.

On July 21, in Sarov, Mother Arsenia communed of the Holy Mysteries for the last time. She was no longer able to go to the All-Night Vigil. According to the testimony of her cell attendant, Agnia, late in the evening, just before her repose, Mother seemed to have seen something joyful. She gasped once or twice, her face brightened, then she let out her last sigh, and the ascetic peacefully departed to the Lord, without a groan, without any torments. Her eyes remained open, as though she continued to see. Her cell attendant closed them, marveling at such a peaceful, painless repose.

Mother’s body was taken to her home monastery, and only there, after her death, did the sisters learn of another form of the abbess’ asceticism. It turns out that despite her poor health, Mother Arsenia, emulating the ancient ascetics, wore heavy iron chains on her body, exhausted by labors and illness.

After the funeral, many people said they experienced an unearthly, blessed peace during the panikhida for Mother Arsenia. Remarkably, the grief receded, and a joyous feeling filled their hearts with peace.

In one of his teachings, St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), whom Mother Arsenia greatly revered, said: “There is no doubt that the reposed is under the mercy of God if at the burial of his body, the sorrow of those present is dissolved by some incomprehensible joy.

OrthoChristian.com will be posting some of the instructions of this great and righteous nun, Abbess Arsenia. Stay tuned!