Footnotes marked “—Trans.” are by Monk Sophrony (Vishnyak), who translated this text from Greek to Russian. Otherwise, they are from Archimandrite Athanasios (Papastavrou), a spiritual child of Elder Epiphanios who originally published this text in Greek with the Elder’s blessing.

***

Laboring in this way and not even thinking about the episcopacy, but on the contrary, feeling fear and trepidation before the burden of responsibility of shepherding tens of thousands of people, and having a deep sense of my own insufficiency and infirmity; and also being naturally drawn, as I wrote above, to solitude and obscurity, I never undertook any actions to fulfill even a trace of the “formal requirements” necessary for inclusion in the episcopal elections lists. It gave me peace of mind, because I was thereby spared for life from this kind of… “danger.” “Even if they want to,” I thought, “they won’t be able to make me a bishop. My complete lack of the formal requirements necessary for this, except for a theological education degree, is an insurmountable wall. So, I’m perfectly safe.” And I continued my path, rejoicing and without worries…1

But soon the terrible year 1967 came crashing down, when, according to the amended laws,2 any Greek celibate cleric with a theological education automatically becomes a candidate for the episcopacy. Both the new Archbishop and the new members of the Synod, except for two who were closely associated with me before, but especially since 1965, when they separated their position from the majority of the hierarchs, predicted a metropolis for me. I decisively and categorically refuse, but they don’t give up. There were two main and particular “opponents,” cruel and relentless “combatants” against me, who were most closely associated with me: the ever-memorable Metropolitan Dionysios of Trikkis and Metropolitan Meletios of Kythira. I experienced nightmarish hours and days. I will tell you about the most terrible scene for me.

Metropolitan Meletios of Kythira We’re sitting, on the eve of the episcopal elections, in the Metropolitan of Kythira’s room at the Omonia Hotel in Athens (I loved and greatly revered him, but he also loved me very much and revered me exceedingly. We had known each other since he was the director of the ecclesiastical school in Kalamata and I was studying theology. Over time, we became very close.). He’s trying various techniques to break my resistance. Before that, the Metropolitan of Trikkis had said to him: “Nothing worked for me. Maybe it will for you.” But… my “citadel” doesn’t fall. Then at some point, this venerable elder, overcome by intense emotion, bursts into tears. His struggle “against me” continues amidst sobbing. “Accept it! Accept! Don’t refuse! Say ‘yes!’ It’s God’s will! The Church is calling you! Accept it! Accept it!...” he cried through his tears. Oh, my God! What a terrible ordeal for me… How to respond? How to oppose it? How to fight under such dramatic conditions? I get up from my seat, fall on my knees in front of him, take both his hands and kiss them, humiliated and distraught. How I didn’t have a heart attack, only God knows. “Geronda, don’t insist,” I whisper, holding my hands on his lap (he was sitting). “Your position distresses me, but I can’t say ‘yes.’ What mean ye to weep and to break mine heart?3 If, as you say, it’s the will of God, then why does God not speak it to my heart? Why doesn’t He give me inner assurance? Why doesn’t my inner disposition change? Why don’t I feel any warmth, even the smallest bit, from the thought of being elevated to the episcopacy? Why, on the contrary, do I feel a chilling cold inside when I think about ascending the episcopal cathedra? I explain this as God’s acceptance of my desire to remain a priest until death. Therefore, He gave me enough illnesses for my conscience to be calm about my refusal, were I to ever find myself in such a position, and also a ‘plausible excuse’ to outsiders. I consider poor health to be another reason that makes me flee from the great burden of responsibility. I believe that God has approved and signed my decision. And at this moment, full of fear and trembling, seeing you, deeply respected Bishop of Kythira, whose image resembles the Biblical Melchizedek, tearfully pleading with me, I am certainly broken by your love and respect—but ice remains ice. I tremble and faint at the thought that I will have to leave the silence of my office, to close my life-giving books, to put aside my pen, to abandon apologetic and polemical discussions with ‘those who oppose the truth,’ to bid farewell to my dear confessional room and plunge into the abyss of bureaucratic troubles, to get bogged down in the inexorable and destructive ‘gears’ of management and the evils inextricably linked with it, starting with small examples of ingratiation and ending with audacious machinations and intrigues, to be ground down by concerns about ceremonies and celebrations, commissions and meetings, receptions of official persons at train stations and airports. I’m not disparaging the episcopal dignity and the work of a bishop, but all of this is not for me; it’s not my measure. My character, my ‘spiritual makeup,’ my way of thinking is meant for something else. Not only does the thought of the episcopacy not touch me, despite everything that is being done for me and my sake all these days, not only does it not strike any sensitive chord in my soul, but it arouses the strongest repulsive force in me. Why is that? Entreat God, since you believe it’s His will for me to become a bishop, to change me. ‘Nothing is impossible for Him.’ I see no other way out. Feeling the way I feel, I can’t accept. Please, I implore you, don’t insist any further. I can’t stand such pressure. I won’t give in, but I’ll simply ‘burst’… Either God will change my inner state by His direct intervention and will melt the ice, that is, make me feel some sympathy, some warmth for the ‘glory of the episcopacy,’ or I will remain what I am. There is no third option…”

Metropolitan Meletios of Kythira We’re sitting, on the eve of the episcopal elections, in the Metropolitan of Kythira’s room at the Omonia Hotel in Athens (I loved and greatly revered him, but he also loved me very much and revered me exceedingly. We had known each other since he was the director of the ecclesiastical school in Kalamata and I was studying theology. Over time, we became very close.). He’s trying various techniques to break my resistance. Before that, the Metropolitan of Trikkis had said to him: “Nothing worked for me. Maybe it will for you.” But… my “citadel” doesn’t fall. Then at some point, this venerable elder, overcome by intense emotion, bursts into tears. His struggle “against me” continues amidst sobbing. “Accept it! Accept! Don’t refuse! Say ‘yes!’ It’s God’s will! The Church is calling you! Accept it! Accept it!...” he cried through his tears. Oh, my God! What a terrible ordeal for me… How to respond? How to oppose it? How to fight under such dramatic conditions? I get up from my seat, fall on my knees in front of him, take both his hands and kiss them, humiliated and distraught. How I didn’t have a heart attack, only God knows. “Geronda, don’t insist,” I whisper, holding my hands on his lap (he was sitting). “Your position distresses me, but I can’t say ‘yes.’ What mean ye to weep and to break mine heart?3 If, as you say, it’s the will of God, then why does God not speak it to my heart? Why doesn’t He give me inner assurance? Why doesn’t my inner disposition change? Why don’t I feel any warmth, even the smallest bit, from the thought of being elevated to the episcopacy? Why, on the contrary, do I feel a chilling cold inside when I think about ascending the episcopal cathedra? I explain this as God’s acceptance of my desire to remain a priest until death. Therefore, He gave me enough illnesses for my conscience to be calm about my refusal, were I to ever find myself in such a position, and also a ‘plausible excuse’ to outsiders. I consider poor health to be another reason that makes me flee from the great burden of responsibility. I believe that God has approved and signed my decision. And at this moment, full of fear and trembling, seeing you, deeply respected Bishop of Kythira, whose image resembles the Biblical Melchizedek, tearfully pleading with me, I am certainly broken by your love and respect—but ice remains ice. I tremble and faint at the thought that I will have to leave the silence of my office, to close my life-giving books, to put aside my pen, to abandon apologetic and polemical discussions with ‘those who oppose the truth,’ to bid farewell to my dear confessional room and plunge into the abyss of bureaucratic troubles, to get bogged down in the inexorable and destructive ‘gears’ of management and the evils inextricably linked with it, starting with small examples of ingratiation and ending with audacious machinations and intrigues, to be ground down by concerns about ceremonies and celebrations, commissions and meetings, receptions of official persons at train stations and airports. I’m not disparaging the episcopal dignity and the work of a bishop, but all of this is not for me; it’s not my measure. My character, my ‘spiritual makeup,’ my way of thinking is meant for something else. Not only does the thought of the episcopacy not touch me, despite everything that is being done for me and my sake all these days, not only does it not strike any sensitive chord in my soul, but it arouses the strongest repulsive force in me. Why is that? Entreat God, since you believe it’s His will for me to become a bishop, to change me. ‘Nothing is impossible for Him.’ I see no other way out. Feeling the way I feel, I can’t accept. Please, I implore you, don’t insist any further. I can’t stand such pressure. I won’t give in, but I’ll simply ‘burst’… Either God will change my inner state by His direct intervention and will melt the ice, that is, make me feel some sympathy, some warmth for the ‘glory of the episcopacy,’ or I will remain what I am. There is no third option…”

I kissed both of his hands again, if memory serves me right, I also kissed his knees, got up (I was kneeling, as I said earlier), and ran out, staggering with agitation, and he shouted after me, “I’ll be waiting for you tomorrow with a positive response…” There were other attempts from him and others, but none of them had the sharpness, intensity, and drama described here… Finally, glory to God, endless glory to God, the “fights” ended favorably for me… In December 1967, I was asked to become the secretary of the Holy Synod, but again I refused. Later, when the cathedra of one large and “enviable” metropolis became vacant, new pressure came from two powerful hierarchs, but again I answered in the negative… And since the conversation about it took place at my home, in my office, I added, “Should I give up Chrysostom and Basil and deal with bureaucracy?4 Out of the question! Bureaucracy is necessary, I’m not arguing, but it’s not for me. There are so many people who want it…”

Do not think, dear Athanasios, that my refusal, my opposition, contains anything worthy of admiration. No, my child! Worthy of admiration is the one who desires the episcopal dignity, is drawn to it, but doesn’t strive for it, doesn’t ask, doesn’t hunt for votes,5 doesn’t make concessions and compromises with his conscience, doesn’t engage in sycophancy and flattery, although he knows that without it his desire might not come true, as indeed happened with many of the worthiest laborers of the Church. But as for him who, by virtue of his character, temperament, and subjective predispositions, looks at the episcopal dignity as a “frozen lake” or a “fiery furnace”— why is he worthy of admiration if he refuses to plunge into it?... I am equally unworthy of admiration for another reason. You have been to hundreds of services celebrated by me, and you’ve sung them with other chanters, and you may have noticed three things:

a) That I don’t wear any liturgical distinctions, not even the epigonion. In the twenty-five years of my priestly ministry, there have only been a couple of times, no more than ten, when I wore my archimandrite vestments—that is, one simple non-jeweled cross and the monastic veil.

b) That I have never worn fancy, expensive, or flashy vestments. One simple set of vestments of “pique” or “satin,” or even silk (made in the Kalogreon Monastery in Kalamata6) with crosses or the Chi Ro is more than enough for me to serve the preternatural Sacrament of Extreme Humility…

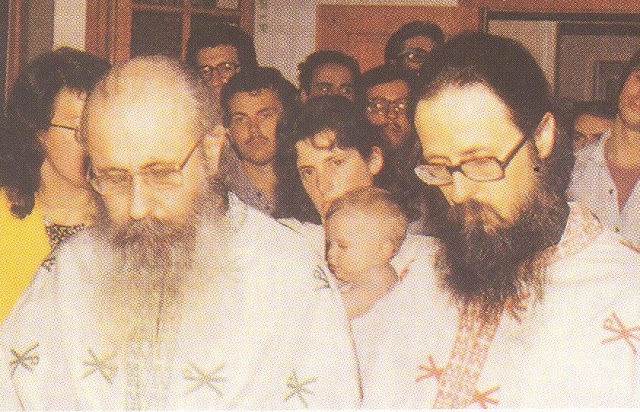

Fr. Epiphanios with the abbot of the Kecharitomene Monastery, Fr. Hesychios

Fr. Epiphanios with the abbot of the Kecharitomene Monastery, Fr. Hesychios

c) I very rarely lead the services. Respecting the age of the retired priest7 Fr. George Papageorgiou, with whom I serve in the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs, I make him lead the services, threatening that otherwise I won’t serve at all, despite his protests and dissatisfaction.8 And when at the frequently served “half-night Vigils,” with the concelebration of three, four, or even five priests, Fr. George refuses to head the service (although he’s the oldest), fearing he might be misunderstood by the other priests—theologians and possessors of Church ranks—I make the first among the others lead the service, appealing to the law of hospitality, which obliges us to implement the Pauline commandment: In honor giving preference to one another.9 When I meet an objection (“You’re an archimandrite—you have the primacy here), I put forward a disarming argument: “Since the primacy belongs to me, since I’m the ‘primate,’ I give you my place. So, give in, ‘for it seemed good’ to the primate. Primacy is not an obligation, not a duty, but a right. And rights can be ceded. According to the historian Eusebius, when Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna visited the Roman Anikita, he ‘offered Polycarp to celebrate the Eucharist in the church.10 So, take the main place and leave the objections…’ Your father had the same experience when he visited the hesychasterion11 and we concelebrated.

So, for all these things, I am not worthy… of admiration (!) for one simple reason: because I like them, they “express me,” they fully correspond to my disposition and character. All of them not only “cost” me nothing, but also please and inspire me. The opposite of them would be suffering and trial for me. It’s those who like luxurious, shiny, and gold-woven vestments, who have a special fondness for them, who are captivated by the idea of presiding, and preeminence,12 and standing before others, yet, despite this, overcome themselves and avoid these things, who are worthy of admiration. But what admirable deed is it for those who feel a repulsion to all things luxurious, flashy, and distinctive things to avoid what does not entice them but rather repels them?

Of course, this is the case because we, both kinds of people, are far from perfection and passionlessness. If we were perfect, then, as St. Maximos the Confessor says, we would look at such things dispassionately and indifferently. That is, we wouldn’t make a distinction between expensive and cheap, high and low, important and insignificant, porphyry and rags, first and last place. There wouldn’t be anything attractive or repulsive, anything to strive for or reject, desirable or undesirable. We wouldn’t have preferences or grievances. Everything would be ordinary for us, the same, and equally indifferent…

To be continued…