Preface by Greek to Russian translator

We offer a translation of a text that is, in our view, a masterpiece of Greek Christian writing of the twentieth century. The author of this text, Archimandrite Epiphanios (Theodoropoulos) of blessed memory, is already quite well-known in Russia for his books and articles. However, the present text is something special. It’s not simply one of the countless writings from Fr. Epiphanios on important spiritual and ecclesiastical topics—it’s a confession of his soul in which he himself expounds upon his priestly path. Confident that the text would never be published, Fr. Epiphanios tells us about aspects of his righteous life that only his closest spiritual children were privy to. These lines breathe the sanctity of Geronda Epiphanios. We are certain that the thoughtful reader, be he a cleric, a servant of the Church, or a simple layman, will find great spiritual edification for himself in the pages of this “confession.” We can’t but agree with what the publisher of this text, Archimandrite Athanasios, said to Fr. Epiphanios: “This text belongs to Patristic literature… It should become the property of all Orthodox Christians,” which, with God’s help, we are helping to do.

In addition to the publisher’s notes, we have added our own notes to the text, explaining various realities that may be unclear to readers outside of the Greek tradition, as well as translation features, marked with “–Trans.”

Source: Γέροντος Ἐπιφανίου Ἰ. Θεοδωροπούλου «Περί ἀποφυγῆς τῆς ἀρχιερωσύνης…», Ἀρχιμανδρίτου π. Ἀθανασίου Γ. Παπασταύρου: Προλογικά, Βιογραφικόν, Ἱστορικόν, Ἐπίμετρον. Ἀθήνα: Ἄθως, 2010 (Β’ Ἔκδοσις). Σ. 21–53.

Monk Sophrony (Vishnyak)

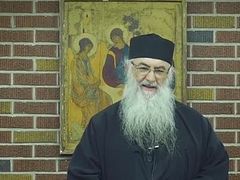

Elder Epiphanios in the last years of his life

Elder Epiphanios in the last years of his life

Introduction

The spiritual children of the ever-memorable Fr. Epiphanios (Theodoropoulos) and people who were simply connected to him or who read his inspiring works were often puzzled: “Why did such a bright and gifted person not only not accept, but, on the contrary, resolutely refuse to serve the Orthodox Church of Christ as a bishop? Why did he choose to remain a simple priest, given that as a metropolitan1 he could have had more opportunities to influence vital issues concerning the current situation of Greek Orthodoxy and the faithful people of God?” These and other similar questions occupied my mind from the very beginning of my acquaintance with Fr. Epiphanios, and I often asked him about it, always receiving a reassuring answer that all in due time and when God pleases, my thoughts on this matter would be at peace.

As the years passed, the changes that Divine grace was working in me directed my thoughts, hopes, and desires from law benches to the foot of the stairs leading to the holy altar. The tectonic shifts occurring in my soul finally led me to diaconal ordination. Before my ordination, I had a long conversation with a revered elder-metropolitan during which there again arose the perplexing question of Fr. Epiphanios’ refusal to accept the metropolitan dignity despite the tempting offers that he received from time to time.

Naturally, I told Fr. Epiphanios about this conversation, adding: “Geronda, I personally feel peace when I’m with you, and my many years of living near you and studying at your feet have experientially taught me that your earthly path and what you choose in life are approved and blessed by God. But I think you should give a sound reply to all those who ask themselves and wonder why you persistently and, as it were, with a firm and inflexible will, refuse to become a bishop in any way.” He gave me a brief glance, calm and at the same time intent, and quietly said: “Alright, if that’s the case, I’ll pray and give you a detailed answer…”

I asked him to forgive me because I felt I had unwittingly plucked at his heart strings. He forgave me with a fatherly smile, and I retired to the apartment where I was living then (next to his own). A few days later, I returned home and opened the door to find a note from Geronda on the floor asking me to come over as soon as I got home. Leaving the door half-open, I went with curiosity written all over my face to ring the bell to his apartment, which, as I said, was next to mine. As soon as he opened up, before I could even ask him anything, he reassured me: “Don’t worry, I have something for you.” He went into his office and took a sealed letter from a folder and handed it to me. “Take it and study it at your leisure,” he said. “But this is strictly for you personally.” But how could I wait until I found some “leisure” time?! As soon as he blessed me, I immediately went back to my place and, of course, immediately opened the envelope and started reading the letter. I was seized with the deepest emotion! I read the letter in a single breath and immediately ran back to him, although it was already late. When he opened the door, I made a low bow and stammered out: “Geronda, this text belongs to Patristic literature and should become the property of all Orthodox Christians. I can’t keep it a sealed secret. That’s not what God wants.” His first spontaneous reaction was completely negative. He didn’t want anyone to read his confession “from the depths.” But I wouldn’t give in, until finally, after several months, he permitted me to publish the text a few years after his repose.

I approach this task reluctantly, because this year marks ten years since his departure to the Lord.2

I can assure you with knowledge of the matter: The reality far surpasses what was written, as evidenced by all those who were spiritually connected with Fr. Epiphanios. But Geronda’s humility wouldn’t allow him to see the greatness of his amazing work and talents.

I have removed only one fragment from the letter (about one typewritten page in length), which was an answer to my personal questions, unrelated to the rest of the text, as well as the name of the metropolitan and the diocese where the meeting and conversation took place that was the cause for this wonderful “apology” to be written. The text has not undergone any other changes. Some explanatory footnotes have been added to the text.

Archimandrite Athanasios G. Papastavrou

***

Personal-confidential3

“OUT OF THE DEPTHS HAVE I CRIED UNTO THEE…”

(“In Defense of My Flight to Pontus,”4 that is,

a confession and apology for refusing the episcopacy)

Athens, January 25, 1986

Feast of our Holy Father Gregory the Theologian

To: Mr. Athanasios G. Papastavrou, lawyer,

student of the Faculty of Theology,

candidate for the diaconate,

through my humility a beloved disciple in Christ

Dear Athanasios!

Rejoice in the Lord always.

When you returned about twenty days ago from … you told me about the circumstances of the meeting with His Eminence … and about the conversation that took place. As you reported, three topics were touched upon: a)… b)… and c) about how I, about whom His Grace spoke with praise and great love, acted badly and contrary to the will of God in refusing the episcopacy, for, as he said, “he is worthy, and the worthy must stand as bastions, not sit idly by.”

…

As for the third question, that is, my refusal to become a bishop, I promised you that in order to calm your mind (although I didn’t see any wavering in you regarding me, at least not noticeably) I would explain everything to you in detail, tell you the truth, unfold the secret corners of my soul, pour my heart out onto paper, provide an “apology,” substantiate my refusal—in a word, I would try to “justify” my position. And I’m doing this because not only His Eminence … but also some other people have a similar opinion about it. And more than anyone else, Metropolitan Ambrose of Eleftheroupoli of blessed memory has most harshly “condemned” me, accusing me of having “offended” and “harmed” the Church.

But before I begin my “apology,” or rather my confession “from the depths,” I think it’s necessary to note this: I don’t consider myself—and this is without any feigned humility—“worthy.” But I’m convinced, unshakably convinced of something else, namely that it’s a great mistake to think that only episcopal cathedras are “bastions.” Of course, they are also bastions (provided they are occupied by capable and valiant men, not “soulless dolls”), but deep deserts, village shacks, and city basements are also bastions when brave and spiritually gifted men live in them. For three of the greatest warriors of the Orthodox faith, who enjoy eternal glory in the Church of Christ—Sts. Theodore the Studite, John of Damascus, and Maximos the Confessor—their bastions were not patriarchal and episcopal cathedras, but poor and obscure monastic cells. But also many holy bishops and patriarchs, standing on the bastions of their cathedras, were dethroned from them and turned the places where they were sent in exile, and the prisons where they were confined, into bastions. And this new apostle and enlightener of the Greek people, the great and incomparable St. Kosmas of Aetolia—from what enviable and glorious stronghold did he carry out his work, so amazing in scope and depth? From the stronghold … of a wooden bench!5

But it’s time to start my “apology.” So, “here is my apology (or rather, my confession) against those who condemn me.”6

From infancy, from two–two and a half years old, that is, from the moment I “knew the world,” I felt a strong and irresistible draw to the cassock, to priestly work. When people asked me what I wanted to do with my life, sometimes I said I wanted to be a priest, and sometimes a bishop. Some of my relatives started contradicting me after a while, saying: “You’ll be a priest, but married” (until the age of twelve I had sisters but not brothers. I was the only son; my two brothers were born later), but I would answer with unyielding tenacity: “No! I’m not going to get married. Get it out of your heads.” And indeed, they weren’t slow to “get it out.” They realized quickly enough that they were laboring in vain…

Fr. Epiphanios’ aunt Alexandra My inborn propensity for the priesthood was enthusiastically cultivated both by my paternal grandmother and my aunt (my father’s sister)—two women of holy life—and the priests of my parish, especially my childhood confessor, who reposed in 1946 or 1947, and then his successors. Since I’ve raised the topic of these two righteous women, I feel the need to emphasize the significant influence they had on me, not so much in word as in their “living” example. This example inconspicuously and imperceptibly but constantly carved indelible traits in my soul. I’ll mention one illustrative case. They both kept the Church fasts with extreme strictness. Even when they were sick, for example with a cold, they refused to break the fast. Although my parents were God-fearing, they both had chronic diseases of the digestive system (one had stomach ulcers, and the other colitis), so they fasted little and not strictly. I admired the “heroism” of my grandmother and aunt and under the deep influence of their example, I voluntarily began, from the age of four, to keep all the fasts of the Church year, and strictly. Since I was very thin and weak, my father was worried about my health and suggested that I eat, but I remained adamant. Whenever he tried to pressure me somehow, I would threaten to stop eating altogether if they didn’t provide me with fasting food. My ever-memorable father, knowing that his little progeny was distinguished by obstinacy in his decisions and therefore was able to carry out these threats, backed down and thus always had fasting food for me, to which he would add various things (dried fruit, nuts, and so on)… Eternal memory to both these righteous women, especially my aunt, who served me and my cause with inimitable selflessness until her last breath in March 1983!

Fr. Epiphanios’ aunt Alexandra My inborn propensity for the priesthood was enthusiastically cultivated both by my paternal grandmother and my aunt (my father’s sister)—two women of holy life—and the priests of my parish, especially my childhood confessor, who reposed in 1946 or 1947, and then his successors. Since I’ve raised the topic of these two righteous women, I feel the need to emphasize the significant influence they had on me, not so much in word as in their “living” example. This example inconspicuously and imperceptibly but constantly carved indelible traits in my soul. I’ll mention one illustrative case. They both kept the Church fasts with extreme strictness. Even when they were sick, for example with a cold, they refused to break the fast. Although my parents were God-fearing, they both had chronic diseases of the digestive system (one had stomach ulcers, and the other colitis), so they fasted little and not strictly. I admired the “heroism” of my grandmother and aunt and under the deep influence of their example, I voluntarily began, from the age of four, to keep all the fasts of the Church year, and strictly. Since I was very thin and weak, my father was worried about my health and suggested that I eat, but I remained adamant. Whenever he tried to pressure me somehow, I would threaten to stop eating altogether if they didn’t provide me with fasting food. My ever-memorable father, knowing that his little progeny was distinguished by obstinacy in his decisions and therefore was able to carry out these threats, backed down and thus always had fasting food for me, to which he would add various things (dried fruit, nuts, and so on)… Eternal memory to both these righteous women, especially my aunt, who served me and my cause with inimitable selflessness until her last breath in March 1983!

The years passed, and here I am a student of the Faculty of Theology. From the time I was a schoolboy, studying the Fathers and visiting monasteries raised many questions in my soul about the “episcopal glory.” During my college years, these searches were put to an end. Not, of course, because of the teachers’ lectures, but thanks to deeper and constant personal communion with the Patristic texts. My eyes have “understood and beheld” and my mind has well comprehended the meaning of the vanity of all worldly things, the impermanence and transience of “pitiful human glory.” Add to this the fact that by nature and spiritual disposition I have always felt an aversion to “putting myself forward” and “showing myself off,” to noise and “praise,” and have been drawn to solitude and obscurity, convinced by daily experience that the episcopal dignity is accompanied by much worldly splendor, much grandeur, pomp, ostentation, noise, demonstrativeness, and publicity. Additionally, there is much “obedience” to every directive of the “lawfully ruling authority.” Thus, I was called either to combine incompatible things within my soul, to unite opposites, to combine the mutually exclusive, or to realize, in accordance with my inclinations and aspirations, my “dream” (that is, my plan) for my future. Backstreets, shadows, “corners,” “laying low”7 pulled at me like a magnet; while noise, promotion, applause, “the hum of the crowd,” many years, formality, “splendor,” “protocol,” high cathedras, episcopal or otherwise, repelled me “with untold force” and gave me a “spiritual allergy.”

The ever-memorable professors P. Bratsiotis and L. Philippidis repeatedly and strongly urged me (I still have a letter from Philippidis about this) to direct my steps towards the university scene, but my fellow countryman K. Giorgoulis, the chief secretary of the then-Ministry of Education, offered me a three-year stipend to study abroad. I thanked him and refused without thinking twice… To illustrate just how averseI have been to self-promotion and “advertising” ever since I was child, I’ll tell you this story. Metropolitan Chrysostomos (Daskalakis) of Messinia of blessed memory wanted to tonsure me as a reader when I was a senior in high school. He chose Holy Pascha Sunday to do it, namely, during the festively and popularly celebrated Agape Vespers. I asked him if he would be satisfied with the tonsuring alone, or whether he intended to speak as well. “Of course!” he said in his usual domineering and majestic manner, adding: “Young men like you should be held up as role models. That’s what I’m going to do!” “In that case,” I said, “I won’t even come to church for Vespers.” Unaccustomed to being contradicted, he literally jumped up. He cast his scorching eagle-eye gaze upon me. “What did you say?” he exclaimed in anger. “I won’t even come to church,” I calmly repeated. “I can’t endure the agony of being praised before the whole congregation in a packed church. If you don’t say anything about me then I’ll come and receive the tonsure, if that’s what you want. Otherwise, I won’t come.” Acquainted with the unyielding nature of this “stiff-necked” youth from previous experience, he changed his tactic (at which he was a master) and began to explain to me in the most affectionate tone why I should agree (for example, that it would be “a convenient opportunity to encourage parents to cultivate love for the Church in their children,” that “my example proves that the conscious children of the Church are excellent learners,” and so on). He concluded: “Don’t upset me! That’s not right! You know how I love you!” “I know,” I said, “and your love is deeply touching to me. But it’s precisely because you love me that my torment cannot bring you joy. And it would be tormenting for me to hear, before so many people, the praise and panegyrics that your great love for me would inspire, and moreover with great exaggeration. At least, since you really want to speak, do it at some simple Saturday Vespers when there are no more than 100 or 150 people in the cathedral (note: I’m talking about what happened more than forty years ago). So instead of torment, I’ll just have to endure suffering and testing…” In the end, I was tonsured, although “with praises,” during Vespers for Thomas Sunday (that is, on Saturday evening).

However, besides my passionate desire for the “corner,” for obscurity, inconspicuousness, another desire has been warming my heart with an “immaterial fire” since my college years: to serve the Church of Christ selflessly. The words of the Apostle Paul: I have coveted no man's silver, or gold, or apparel. Yea, ye yourselves know, that these hands have ministered unto my necessities, and to them that were with me (Acts 20:33-34), and we labour, working with our own hands (1 Cor. 4:12), Even so hath the Lord ordained that they which preach the Gospel should live of the Gospel. But I have used none of these things … for it were better for me to die, than that any man should make my glorying void… What is my reward then? Verily that, when I preach the Gospel, I may make the Gospel of Christ without charge (1 Cor. 9:14-15, 18), and others like them (1 Thess. 2:9, 2 Thess. 3:8), sounded like exalted angelic melodies in me and touched the most sensitive (considering that I had a natural contempt for money) strings of my soul. I want, I strive, I “thirst” to emulate him. It was fitting, I thought, to imitate him. But how? I came from a family that is neither poor nor deprived of belongings, but to live dependent upon my parents—that’s unacceptable. That’s how I thought. The Apostle Paul ma[d]e the Gospel of Christ without charge, but labored with [his] own hands. I came up with the idea of learning to type, to do this “handiwork” two to three hours a day and so minister unto my necessities, and not receive a penny from my priestly stole. There will be no shortage of work. About a dozen of my friends and classmates are already studying law. When I become a cleric, they’ll be lawyers. Will they really refuse to give me some of their work that needs typing? Of course not! An easy and reliable solution… (In the end, I found another solution, ideal for me, “because God had provided something better for me”8).