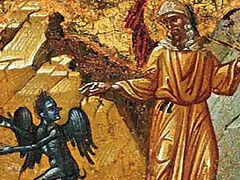

In the weeks leading up to Great Lent, a list of commemorations begins of people who pleased God with a particular and strange life, which is called monasticism. Today we commemoration St. Anthony the Great, the father of monastic life. From the point of view of the pleasures of life, if we dedicate our lives to pleasure—for example, eating, drinking, buying things, taking vacations, swimming, getting a suntan, then returning home—then the lifestyle of a monk would be considered madness. But from the point of view of the end of life, if we jump ahead to what no one will escape, then monks are the smartest of all, they are smarter from the start. They understood what is ahead, and decided to die earlier to the world with its fleshly lusts and temptations, instead of letting the flesh just die by itself and be brought out feet first. Because we will all get smarter, terrifyingly and unexpectedly, and all the mysteries of God’s world will be revealed to us terribly and wondrously—the angelic world, the depths of hell, the brightness of paradise. It will all be revealed to man. And any dead man is a hundred times smarter than any living man, because he sees what the living can only guess at. So, we can consider the monk to be smarter than the rest, more precocious than the rest. And one of these is St. Anthony the Great.

It’s very hard for us to follow their example in life, because we have to act according to our own level in life. For example, a child in physical education class cannot follow the example of an Olympic athlete—he’s not capable of duplicating the athlete’s training, etc. So, we are faced with a choice—whom should I take as an example? You see, the Orthodox faith is a monastic-loving faith. And according to the expression of St. John Climacus, the angels are a light to monks, and monks are a light to laypeople. That is, the monk should take his example from the angels, while the layperson should take his example from the monks. Our Eastern Orthodox society is monastic-loving. But there are comparatively few people living in the world who have attained sanctity of life and spiritual gifts, and moreover in our days, everything is fallen and slack, people have weakened and grown weary, fallen and withered, they’ve fallen and can’t get up. This relates to the entire universe; it should be clear to your hearts that the universe is falling apart, that everything is coming apart at the seams, everything that seemed steadfast, firm, and invincible is falling apart—not here, not in the Middle East, but everywhere. If your soul is sensitive, you can feel this entropy of life. So it’s very hard to emulate the true monastic life. St. Anthony said that in the future, men will not be ashamed to call themselves monks, but they will live in large houses in cities; they will not be ashamed to say that they are the disciple of say, Anthony, or Pachomius, or others; they will have many books on the shelves written by these fathers, and all their monasticism will consist in these books on the shelves, but by their trapeza, by their standard of life, they will live like laymen, even better than them.

This has already happened long ago. From this garbage came Protestantism. Martin Luther in his time was aghast at what the prelates and monks were up to, and so he decided to “renew” it all, because it all stank; and so he created this new trend called Protestantism. That’s understandable. And it’s understandable today, because some have grown slack, others have gone off the deep end, while the true monks are not visible—for the sake of their own salvation they have hidden themselves from our view, they live somewhere keeping a low profile, so that they would not perish. Because sanctity “dries up” under the gaze of others. Also in St. Anthony’s saying is that there will be monks in the end times who will be equal, even higher than us [the monks of St. Anthony’s time]. This is a general segment in the sayings of the holy fathers of Egypt, Sinai, Gaza, etc, who said, “What have we done? To the best of our ability, we have fulfilled all the commandments. What will they do who come after us? They will do half of what we have done. And those who will come at the end times—what will they do? They will not do anything. But if they preserve their faith, they will be higher than us.”

That is, today is the time when we need faith—to preserve it, spread it, explain it, inculcate it, protect it, and so on. This is because faith is what saves a person. But acetic labors are as if being taken away. It’s hard to imagine that a stylite, for example, might arise somewhere near us—although it’s not impossible at any time. But there is another saying that comes from those times, that the in monasteries it will be like in the world, and in the world, it will be like in hell. Let me remind you that our faith is monastic-loving. For us, the destruction of monasteries is the same as the destruction of our civilization. Our people love monastic church services, they live just as St. John Climacus said—the angels are a light to monks, and monks are a light to laypeople. We know that monks have long services, that they sing with compunction, dress and eat modestly, that they make prostrations, pray at night—and we also want to do these things. And so, we come from this weak civilization, where it’s slack, and sins crawl in from all sides; and people come to the monastery from this hell. I was talking not long ago with a friend who is a monk in a monastery in the city, who said, “We live as if at the bazaar, because thousands of people come in from all around.” The monks are tormented by this. There is plenty of money because the pilgrims bring it, but it’s murderous to monasticism. Women with their lipstick and perfume, tourists with their cameras—it’s murder to monasticism. And all the monks suffer from this; but on the other hand, he says, “Well, what can we do? They are coming from hell.” In the monastery it’s like in the world; is it any surprise now to see a monk with a mobile phone? Or a monk driving a car? No, not at all. The monks are as if in the world, and in the world it’s as if it were hell. This is our life. I don’t see anything brighter on the horizon. I don’t want to soothe you with false hopes of anything better—it will only get worse. But the spirit of podvig remains. It is a manifestation that was born in the bowels of Orthodox consciousness.

Monasticism was not the product of people’s plans. There were never any analysts, no strategic thinkers, who thought, “Oh, it’s bad that martyrdom ended—there are no more people who are capable of having their hands chopped off or their eyes plucked out for the sake of the name of Jesus Christ. Now in the Christian Church there are lords and secular people, the spirit has fallen. What should we do? Let’s preserve that spirit of early Christianity! How do we do it? Let’s have some people go to the desert and eat and drink nothing, and read the Psalter all day.” No, there weren’t any such strategic thinkers who thought all this up, made a plan to preserve the spirit of true Christianity. Early Christianity was a normative life, when all property was shared in common; everyone was a brother or sister to each other, because they all received Communion together. How do you preserve all this? Monasticism arose out of the desire to preserve the spirit of authentic Christianity—the spirit of self-sacrifice, the spirit of brotherly love, the spirit of looking toward the end; because Christianity is eschatological, it sets its sights on the end of the world. We are continually looking to the end of the universe, because it will come, and will not tarry. And the Lord will return. We think about our own death always, because it only makes sense to think about this most important moment in our lives. It’s the most important day, after our birthday. One would have to be a complete imbecile not to think about the day of his death. “Let’s eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we will die.” The apostle Paul cites this as the creed of a total idiot. How can someone think he won’t die? How? Especially with all these sicknesses… Everyone’s abuzz about these sicknesses; mention death and they’re also abuzz. But mention prayer and they’re silent. Mention life after death—they’re silent. They don’t want to think about it. They have no faith.

And so, today, in remembering St. Anthony, we remember that monasticism is holy, pure; it’s what the salvation of our land come from. Dostoevsky said that the salvation of Russia always came from the monasteries. From beyond the walls some unknown monks always came out and talked to people about spiritual renewal, changing one’s life, and sobriety, from there always came salvation. Why shouldn’t it come from there now? But remember, beloveds, that the spirit of this world is the spirit of sensuality, ambition, wrath, indifference. While in the monastery they live like yesterday’s laity. Monks now live as pious laypeople did two hundred years ago. Pious people in the world lived like today’s better monks. But we can nevertheless take something from St. Anthony. For example, an angel once came to St. Anthony and told him that he hasn’t reached the level of perfection of one shoemaker in Alexandria. So St. Anthony got up on his weary old legs and went to Alexandria to find the shoemaker. He asked him, what do you do to please God so? The shoemaker thought that St. had him confused with someone else, but the saint kept probing to find the man’s secret. Finally, the shoemaker said that every day when he gets up from his bed, he says to himself, “All the people in Alexandria are better than me. All of them will go to paradise, only I will be condemned to suffering. I keep that thought in my heart, and with it I do my work. With this thought I also go to rest.” He kept this teaching, this though in his heart that he is worse than everyone. And this is why St. Anthony arose and left his place of asceticism for Alexandria—to learn this lesson. He thought, “One can remain in one place and keep a saving thought in his mind, and be saved…”

From a sermon given on the commemoration of St. Anthony the Great, January 29, 2023.