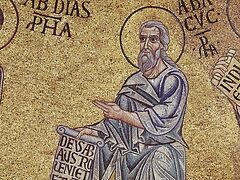

Photo: fotoload.ru The work of the prophet Haggai is short and easy to miss; it is a mere two chapters in our Bibles sandwiched in between the books of Zephaniah and Zechariah. If you are flipping quickly through the final pages of the Old Testament he easy to miss. After ploughing through longer works such as those of Isaiah (66 chapters), Jeremiah (52 chapters, plus 5 more chapters of Lamentations), and Ezekiel (48 chapters), Haggai looks positively puny in comparison.

Photo: fotoload.ru The work of the prophet Haggai is short and easy to miss; it is a mere two chapters in our Bibles sandwiched in between the books of Zephaniah and Zechariah. If you are flipping quickly through the final pages of the Old Testament he easy to miss. After ploughing through longer works such as those of Isaiah (66 chapters), Jeremiah (52 chapters, plus 5 more chapters of Lamentations), and Ezekiel (48 chapters), Haggai looks positively puny in comparison.

It is not only that his literary remains are few in comparison to others in the Old Testament canon. Haggai himself lived and worked as part of a post-exilic community that was few in number and puny in power. This must have been all the more frustrating for him and his contemporaries because the former prophets (ones like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel) promised a glorious future for Israel once they returned from exile. God would enlarge them, enrich them, empower them; He would make Jerusalem the epicenter of Israelite dominance in all the world so that all the nations would flock to Jerusalem offering gifts and worshipping Israel’s God.

So, Haggai and his contemporaries must have repeatedly asked themselves, where was all this glory anyway? A few brave souls left their thriving family businesses in Babylon and Persia and straggled back to a ruined land. There they found themselves surrounded by hostile neighbours, both at home and abroad, with Israel a backwater province of the still-invincible Persian empire. Later the Persians would be replaced by the invincible Macedonian power of Alexander the Great, and then Judah would become the plaything of the quarreling Egyptian and Syrian powers, and finally the subservient slave of Rome. The promised glory never arrived. The world was still full of big powerful players, and Israel was still small and powerless, and the brief fling at power by the Hasmoneans was the exception that proved the rule. The people of Israel now were mostly confined to the land formerly occupied by the tribe of Judah, the land surrounding Jerusalem. That was why they came to be called “Jews”. Some glorious future!

We see this frustration and this temptation to despair as a throbbing subtext in every line of Haggai’s message. The people who trickled back in depressingly small numbers complained that they were not working on building the Temple because “the time has not yet come to build the House of Yahweh”. Haggai rounded on them, and retorted, “Is it a time for you yourselves to dwell in your paneled house while this House lies in ruins?” He pointed out the results of their negligence: they had sown much and harvested little and were struggling. That, he declared, was because of God’s judgment—when you brought the harvest home, God blew it away (Haggai 1:2-9). The answer was to repent and attend to building God’s House.

Finally they did work and build the House, but it was depressingly tiny and poor compared to the previous House built by Solomon. Haggai was again at their elbow to encourage them: “Who is left among you that saw this House in its former glory? How do you see it now? Is it not in your sight as nothing?...Once again, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land; and I will shake all nations so that the treasures of all nations shall come in and I will fill this House with splendour, says Yahweh of Hosts. The latter splendour of this House shall be greater than the former” (Haggai 2:3-9). That splendour, of course, would come with Christ, and the splendour would be a spiritual splendour, adorning a spiritual House (compare Hebrews 12:26-27; Ephesians 2:19-22; 1 Peter 2:4-5). But in Haggai’s day, the success and power of God’s people were depressingly small.

Once again we Orthodox in the West live in a day of small things, small churches, small numbers, and small victories. Admittedly greater numbers now thrive in eastern Europe, Ukraine, and Russia, as people there once again honour and embrace the Orthodox faith. But here in the spiritually dying and decadent West we Orthodox are small, tiny, and embattled. In a world of big people, we are very little. In many census numbers we show up alongside “Protestant”, “Catholic”, “Jew” and “Muslim” as “Other”, scarcely making a demographic mark.

We are sometimes tempted to cope with the pain of puniness by retreating into the glory days of history—which is doubtless why we still insist on calling Istanbul “Constantinople” and dressing our bishops in imperial finery. Sometimes we cope by shyly trying to impress the western world with how fashionably relevant we are in hope of regaining some greatness.

Such was one speaker at a March for Life in Washington who gave a speech “affirming the gift and sanctity of life” and who could not resist adding “At the same time, we also affirm our respect for the autonomy of women”—a meaningless phrase in this context, offered only as a sop to the feminist left whose approval he hoped to gain. (Not surprisingly, said speaker also made a point of travelling to another country to baptize the adopted children of a homosexual couple.) Common to these responses is the reluctance to accept that we are now little people in the land of big.

I sympathize. When my own people at St. Herman’s look around they see vast crowds filling Catholic churches for Mass and crowds of Evangelicals piling in to listen to praise bands. By comparison we are very tiny. And it’s hard to be small. It’s hard to be an Orthodox here in the West.

The Prophet Haggai reminds us that there is a day to be small and that a wise heart will leave questions of numbers, growth, and influence in the hands of God. Soon the heavens and the earth will be shaken once more, as Haggai foretold, and God will destroy the strength of the kingdoms of the nations and overthrow the chariots, and their riders will go down (Haggai 2:22). Until then we wait with patience, as Christ’s little flock. We refuse to be cast down or discouraged. It is the Father’s good pleasure to give us the Kingdom (Luke 12:32).