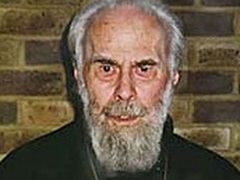

Archpriest Maxim Nikolsky lives in the UK and has served in parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate in this country for many decades. He has talked about his ministry and the people who influenced him.

—Father Maxim, your blessing. Please tell us about yourself. How did you end up in the UK?

—I was born in Kiev. During the Second World War, when the Germans entered the city, my parents, like many others, left Kiev. And through Europe they eventually got to England. It was easy for me to learn English. It is not difficult for any child to learn a language, and after a few months you already can communicate with other children. Then I graduated from school and a university here, and became a teacher. I grew up in ROCOR. During my youth, there were very few Orthodox churches in the country, and we only traveled there for the major feasts several times a year. When I was in ROCOR, I got to know the Moscow Patriarchate and met Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. But it was much later, when I started working and teaching.

—How did you decide to become a priest?

—When I was thirty, I decided to go and study again. And then I met Associate Professor Sergei Hackel, the future archpriest, with whom we later became friends. But at that time I was not yet acquainted with Vladyka Anthony. I met him when I graduated from the second university and we moved to live elsewhere. We attended a ROCOR church, where Archbishop Nicodemus (Nagaev; 1883-1976) served. He was a general in the First World War, then became a priest and archbishop.

But when we moved, we started attending the nearest church—it was in Oxford. And Oxford is the Moscow Patriarchate. We attended it, and on the great feasts we went to the Holy Annunciation Convent (ROCOR). It was headed by Mother Abbess Elisabeth (Ampenoff; 1908-1999). I met Vladyka Anthony in the Moscow Patriarchate, and over time he ordained me deacon. So I served as a deacon in Oxford. And a few years later, he ordained me priest. We had a joint church with the Greeks in Oxford. It was originally consecrated by a Greek bishop, Vladyka Anthony and a Serbian bishop. At that time we served together, there was a very friendly and good atmosphere there. But I also traveled to London regularly to serve with Vladyka.

—Were you his spiritual child?

—Yes, I was.

—Please tell us about him. How would you describe his personality? Can you remember how he stood before God at the Liturgy, how he prayed?

—Of course, it’s very easy. He was a man of prayer. Clergy rarely pray this way, with such depth. When he prayed, there were no conversations in the sanctuary—something that unfortunately does happen. He himself didn’t talk. Like many hierarchs, he prayed without a service book, because he knew all the services by heart and did not need prompting. And he would often stand with his eyes closed between his exclamations. In his declining years he leaned on his staff because it was hard for him to maintain balance—he was ill towards the end of his life.

He had a very pleasant voice, which he raised when he gave exclamations or preached a sermon. He never raised his voice at anyone. However, there was one occasion when he scolded the whole congregation from the ambo after the Liturgy, after someone had offended a mother with a child in the middle of the church the previous week. The child was crying, making noise, and someone told his mother rather rudely to leave the church because the child was hindering his prayer. Vladyka said that it must never happen again and that the parishioner in question had not prayed enough if he could do this. But Vladyka, as I said, always insisted that there should be silence and a prayerful state in church, and not noise.

Vladyka Anthony at the Diocesan youth camp in 1961. Photo: Antsur.ru

Vladyka Anthony at the Diocesan youth camp in 1961. Photo: Antsur.ru

When Vladyka came to the UK, he did not know English. He knew Russian, French and German, but did not speak English and learned it after moving to the UK. And when he became a bishop, he decided that since he was in Britain, he should preach in English. He would write his sermons on paper, writing down what he wanted to say. And one day a parishioner told him (everyone called him “father”, although he was a hierarch, because he was a father to everyone): “Father Anthony, we are very bored listening to you.” Vladyka was surprised, “Really?” The parishioner replied, “You know, yes, it’s boring. You’d better speak without a paper.” Vladyka wondered, “But why? After all, I make mistakes when I speak.” The parishioner answered, “Yes, but when you make mistakes, it’s so funny and interesting to us.” Vladyka took it into account and began to speak without a paper. And after this, he had brilliant English.

—What was his pastoral approach to people? What was his attitude towards the sacrament of confession?

—When I came to his parish, he rarely heard confessions, and he heard confessions only of specific people, not the whole congregation. He had a very careful attitude towards this sacrament and showed understanding to every individual person. Everybody who spoke with Vladyka felt that he was the most important person for Vladyka at that moment. A film was made about him, called, The Apostle of Love. He really treated everyone with love. He could be strict, but love always came first. Vladyka felt people keenly. If someone had a really serious problem, he had access to Vladyka; although of course, as an archpastor he was busy.

—Do you think he acquired this love, or did he always have it?

—I didn’t know his mother. Perhaps he inherited some traits from his father—an understanding of life, people and God Himself. If you recall, his meeting with the Savior took place when he was a young man. After listening to one theological lecture, he was indignant: “How is it? It’s impossible!” Then he went home and said: “Mom, do we have a Gospel?” Of course, they had one at home. He opened the Gospel of Mark, and as he would often later recall, he began to read it, read several chapters and suddenly felt that Christ was standing next to him… Before that, he hadn’t wanted to go to church, being an interesting young student. But at that moment, he felt Him. He couldn’t see, but He knew that Christ was there.… He had knowledge, wisdom, and love. It seems to me that we have no other archpastor who would speak so simply and so deeply at the same time. He spoke directly, like a close friend and a father. And it is love too. Unfortunately, we don’t feel it everywhere…

Vladyka Anthony at the diocesan conference in May 1985. Photo: Antsur.ru

Vladyka Anthony at the diocesan conference in May 1985. Photo: Antsur.ru

—Father Maxim, could you share with us what else you learned from him?

—Of course, Vladyka’s influence on everyone who served in London was great. He ordained all the clergy in the cathedral. He knew everyone very well. And you could just see how he lived. And he lived very modestly. He cooked for himself and cleaned himself his small cell, which was at the cathedral. Many people were happy to give him a lift whenever needed: sometimes he called them when there were urgent matters, and several people were always ready to give him a lift. But mostly he traveled on his own, on foot.

Over time, people throughout the country held him in great esteem. He spoke on the BBC, on the radio, on some channels that broadcast abroad. People in the Soviet Union listened to him often, although those broadcasts were jammed. Fr. Sergii Hackel worked for the BBC, and Vladyka would come to him. Many universities invited him to give talks; he had many honorary doctorates from different universities. Major hospitals invited him to talk about pastoral care and medicine as well. After all, he himself had once been a doctor.

—Did he convert many Brits to Orthodoxy?

—Surely, a lot of them, including many influential figures. At the very beginning, the services were only in Church Slavonic, and then they began to celebrate in English. Once a month, he held services entirely in English. And even those who did not convert to Orthodoxy venerated Vladyka. Later, I personally met many people who, being British, remembered Metropolitan Anthony’s words he had spoken in Anglican seminaries, to which he had been invited. He came there and talked about Christianity, but from an Orthodox perspective. He would say: “I’m talking about Christianity. I am a Christian, a Russian to the core, an Orthodox Christian.” Undoubtedly, there were those who converted to Orthodoxy thanks to him. And those who did not convert remembered him all their lives; many of them used his sermons. But, you know, he didn’t write his sermons or books—all his books are his living word.

—Have you met other spiritual people in your life who have influenced you?

—Personally, I did not communicate, because I felt shy and thought how it would be if I approached him, since he saw right through me—I’m talking about St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco.

—Did you see him in person?

—Yes. He would come to London. But I didn’t dare approach him. Once I was at a Liturgy that he served. But to my shame, I did not come up to him when he gave the cross to kiss at the end of the service. I was a student then. Later I began to learn more and more about him...

And there was Elder Sophrony (Sakharov), who founded the Monastery of St. John the Baptist in Essex. I spoke with him, knew him, and visited his monastery in my time.

—What can you tell readers about him?

—He was a man of prayer. He had a sense of humor. When I first came there, he was already very old. Many people flocked to him. People came from everywhere, especially on weekends, and there were always many people there. People could approach him and talk to him.

—What did Vladyka Anthony think about Elder Sophrony? They probably knew each other.

—They certainly did. They were quite close at one time. I met Elder Sophrony at the London Cathedral just when he was having a meeting with Metropolitan Anthony. Coincidentally, I arrived there when Fr. Sophrony was leaving with Vladyka, who escorted him out of the cathedral. At that time, I didn’t actually know about this monastery. The elder said, “Come to us.” And Metropolitan Anthony added, “Yes, it’s nice there.” It was really very good there—there was a truly Athonite spirit. This is a unique monastery, because it is a monastery for monks, where there were also nuns. Of course, they lived as separate communities. And it’s very much like a family, with love. Unfortunately, we are not in communion with them now, since the monastery belongs to the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov)

Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov)

—Please tell us about your priestly ministry.

—I have served at the London Cathedral for over twenty years now. I have two other small parishes, and one of them is situated in the south of England, by the sea. I serve once a month in one, and once a month in the other. I mostly serve at the London Cathedral. Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, many people have come to us. Over the past two years, many people have also come from Russia and Ukraine. Many have lost their homes and left everything, and we should pastor them too. We serve in two languages.

—Father Maxim, there is a theological academy at the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. What advice would you give to future clergy? In your opinion, what is the most important thing in this ministry?

—In my view, in addition to understanding, knowing the services and prayers, the most important thing is not to feel that you have suddenly received some special gift and can now lead or rule people. Unfortunately, this happens sometimes. In the Russian Church, very young men become priests. I know that young priests are ordained in the Church of Greece as well, but they do not have the right to hear people’s confessions for some time because they have no experience. But in the Russian Church, they can do it right away. And there are some incautious young priests who can even say something rude. Of course, this is bad. We should learn from Vladyka Anthony and other good archpastors to treat everyone with love. You can mutter a rude word, and this can offend someone. And this person will say, “I will go to a place where I am well received.”

—In conclusion, can you please give believers living in Russia some edifying words?

—It’s difficult because I don’t live in Russia and haven’t been there for so many years. I think it’s important to stay true to your heart, your conscience, and not be afraid. Everybody should define their values and turn to God: “If it is from Thee, O Lord, help me act, speak and think accordingly. And if not, enlighten me as to how and what I should do.”

—Thank you for your answers.