A talk with with Professor Alexei Svetozarsky, the head of the Department of Church History of the Moscow Theological Academy, about the Baptism of Russia and how the choice of faith influenced the holy Prince Vladimir Equal-to-the-Apostles, those around him and the whole country.

A prince who became a human being

—Alexei Konstantinovich, let’s start with the personality of Prince Vladimir. Do the legendary image and the historical figure agree?

Having become the Prince of Kiev, Vladimir installed idols behind the terem yard: a wooden Perun with a silver head and golden mustache, Dazhbog, Stribog, Mokosh and others, to whom sacrifices, including human ones, were offered.

Having become the Prince of Kiev, Vladimir installed idols behind the terem yard: a wooden Perun with a silver head and golden mustache, Dazhbog, Stribog, Mokosh and others, to whom sacrifices, including human ones, were offered.

—It depends on what you mean by “legend”. When it comes to folk legends, where Prince Vladimir, for example, fights with the Mongol-Tatars (who did not come to Russia until 1223—that is, 208 years after his death), sending Ilya Muromets to fight against them, then everything is clear. That is, his image was so deeply embedded in the national consciousness that various fantastic features were attributed to him and projected into other periods of history. It is no coincidence that he was called the “Beautiful (or Fair) Sun”—no other Russian ruler enjoyed such an epithet.

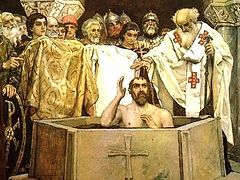

But you and I are obviously interested in something else—whether the historical image from our textbooks is in agreement with reality or not. Clearly, we should not rely entirely on the Tale of Bygone Years—the chronicler undoubtedly strengthened the contrast between Vladimir the pagan and Vladimir the Christian. However, if there is an exaggeration, it is only in numbers. After all, we know about Prince Vladimir from foreign sources as well. And here it does not matter how many concubines he had in his “harem” and how many opponents he killed. What matters is that, having received Holy Baptism, he changed his life radically and fundamentally. Note that he did it in mature age, with deeply ingrained habits and passions. And we know how hard it is to overcome all this in adulthood.

In 983 Vladimir undertook a successful military campaign against the Yatvyags and on the way back to Kiev he began to offer sacrifices to pagan gods in gratitude for his victory. On his return to the capital his closest boyars suggested that the prince make a human sacrifice.

In 983 Vladimir undertook a successful military campaign against the Yatvyags and on the way back to Kiev he began to offer sacrifices to pagan gods in gratitude for his victory. On his return to the capital his closest boyars suggested that the prince make a human sacrifice.

Nevertheless, Prince Vladimir succeeded in this. And this is precisely what makes him different from some European rulers who adopted Christianity for profit, practical reasons and progress. For St. Vladimir it was a matter of moral choice, as can be seen from his later life.

—Did the adoption of a new faith have any impact on the lives of ordinary people? Or did they start wearing crosses, while continuing to live the same way as before

—Of course, the majority of people did not understand the full depth of the Christian teaching, but they accepted it in the simplicity of their hearts, out of trust. It is a distinctive characteristic of patriarchal societies: “This is what our elders did, and we will imitate it.” For example, the Tale of Bygone Years conveys this position as follows: if the prince, the boyars, and the armed force (“druzhina”) had not assessed this faith positively and had not considered it to be their own, then they would have had no reason to get baptized.

The lot fell on the son of a noble Varangian who had come to Russia from the Byzantine Empire and converted to Christianity. The Varangian refused to sacrifice his son, and then by Vladimir’s orders he and his entire family were killed.

The lot fell on the son of a noble Varangian who had come to Russia from the Byzantine Empire and converted to Christianity. The Varangian refused to sacrifice his son, and then by Vladimir’s orders he and his entire family were killed.

—That is, “the prince will not advise anything bad”?

Vladimir’s initial dream was to establish a strong pagan faith capable of uniting all the tribes of the Eastern Slavs, but over time he abandoned this idea and began to look for another religion for his country. There is a well-known episode when ambassadors from the Pope, from Muslims, and from the Jewish Khazars arrived in Kiev. After listening to them, the prince rejected their offers.

Vladimir’s initial dream was to establish a strong pagan faith capable of uniting all the tribes of the Eastern Slavs, but over time he abandoned this idea and began to look for another religion for his country. There is a well-known episode when ambassadors from the Pope, from Muslims, and from the Jewish Khazars arrived in Kiev. After listening to them, the prince rejected their offers.

—Exactly! As for how Christianity influenced the external forms of ordinary people’s lives, the seeds of Christianity, sown by Prince Vladimir, quickly defeated the institutions that were completely incompatible with Christianity—first of all polygamy. In addition, the attitude towards dependent people changed: bondmen (kholops), serfs, voluntary serfs [or zakups, who were granted a loan by their landlord.—Trans.] and so on. People began to see their fellow human beings in Christ in them—as with the same sins as their landlord himself who confessed the Christian faith in the same way. Further, the elements of folk life that were clearly alien to Christianity, in particular stealing each other’s wives during games between villages, quickly became a thing of the past. As for “everyday” paganism, it went into homes, into the background, and still exists in some forms. Actually, we are not unique in this—the same thing happened in Europe.

Among the guests was a philosopher sent from the Byzantine Empire who preached Orthodoxy to the prince. According to the chronicle, Vladimir immediately showed special interest in him, because this faith “impressed him in particular”, but he was slow to make the final decision and sent the philosopher back “with great honor” for a time. The Baptism of the prince himself lay ahead, which would trigger a real revolution in his soul, and if we believe the chroniclers, left nothing of the former heathen and murderer.

Among the guests was a philosopher sent from the Byzantine Empire who preached Orthodoxy to the prince. According to the chronicle, Vladimir immediately showed special interest in him, because this faith “impressed him in particular”, but he was slow to make the final decision and sent the philosopher back “with great honor” for a time. The Baptism of the prince himself lay ahead, which would trigger a real revolution in his soul, and if we believe the chroniclers, left nothing of the former heathen and murderer.

—We often hear that Prince Vladimir baptized Russia forcibly, which means that it cannot be said that Orthodoxy was a free choice of the Russian people. What do historians say about this?

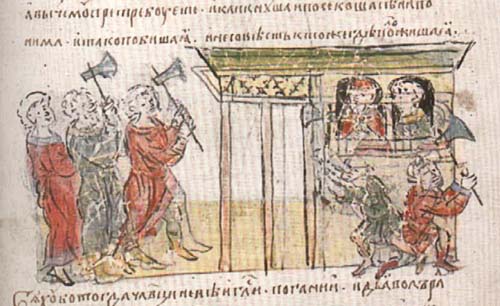

—To begin with, all the accusations of “forced Baptism” boil down to one episode—the Baptism of Novgorod. Information about this can be found only in the Joachim Chronicle. This source is quite late, it is hard to date it, and a number of researchers have doubts about its authenticity.[1] However, it contains some unique information and therefore arouses historians’ interest, especially against the background of other sources on pre-Mongol Russia (and there are very few of them). According to this chronicle, Prince Vladimir sent his uncle Dobrynya to Novgorod in order to baptize this land. He met resistance there, but nevertheless achieved his goal. As a result of his “military operation”, the Novgorodians surrendered and asked for Baptism.

There is an interesting point here: This chronicle mentions the Novgorod Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord, around which a Christian parish had developed. That is, it turned out that there had already been Christians and Orthodox churches in the city even before the mass Baptism of the people of Novgorod. So if we trust the Joachim Chronicle, we have to admit that preaching Orthodoxy was not something completely new for Novgorod, since the way had already been paved for embracing a new faith.

Памятник Св. Владимиру. Купеческий сад. Фототипия Шерер, Набгольц и Ко. Москва. Отсканировано с открытки из серии «Открытое письмо. Всемирный почтовый союз. Россия», 1906 г.

Памятник Св. Владимиру. Купеческий сад. Фототипия Шерер, Набгольц и Ко. Москва. Отсканировано с открытки из серии «Открытое письмо. Всемирный почтовый союз. Россия», 1906 г.

—Can we say that, on the whole, the Eastern Slavs abandoned paganism quite easily?

—Yes, and here we see a difference when compared with some of our neighbors—for example, with Bulgarians, Poles (in 1031–1037 in Poland a powerful anti-Christian uprising swept the whole country), as well as the Polabian and Pomeranian Slavs. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, Slavic paganism was uncompetitive, as it were. Typologically, it seems to me that it was close to Scandinavian paganism, but it was only at the beginning of its formation—there were neither sacred books, nor well-established cult… True, since relatively recently “sensations” have begun to appear in mass media claiming that ancient Slavic “Vedic” books have allegedly been found. But any professional historian can easily identify a fake here. Most often such fakes are the fruit of the deliberate activity of modern neo-pagan sects.

And the second reason why our ancestors received Baptism easily is that the ground had already been prepared. More than 100 years before Prince Vladimir, in the ninth century, the so-called “first Baptism of Russia” had already taken place. That is, by the end of the tenth century some Christians lived in Russia, there were churches, and the Christian teaching was not perceived as something completely new and alien, especially when it comes to the South Russian lands. Thus, all in all, the Russian people were baptized willingly. There were neither mass riots, nor clandestine struggles of any kind.

However, there were several incidents that later became known as the “revolts of pagan sorcerers” (in 1024 in Suzdal; from the late 1060s to the early 1070s—in Novgorod and the land of Yaroslavl), but they can by no means be called “popular uprisings”. Both in Suzdal and Novgorod pagan sorcerers simply initiated “witch hunts” according to their pagan customs, which was regarded as murder by the Christian law. According to the chronicles, the sorcerers sincerely did not understand what they’d done wrong and waited for the prince’s protection. However, there were also cases when pagans expelled bishops (for example, in Rostov Veliky, from where the first two bishops were expelled, and the third, St. Leontius, was slain). However, there is an assumption that the northeastern lands were not only a stronghold of paganism, but also of Christian heresies—first of all, Bogomilism, which influenced the later Slavic-Finnish paganism of the northeast. Again, I should note that all those incidents were local, and not massive at all.

Another reason why there was no active resistance to Christianity in Russia is that services were celebrated in a language that people understood—unlike the Latin rite in Poland and Pomerania.

Nevertheless, we cannot say that with the advent of Christianity, paganism disappeared for good. The so-called “folk culture”, which coexisted with Christianity for many centuries, had absorbed a lot of heathen elements. Even in our days these remnants of paganism sometimes manifest themselves.

Prince Vladimir’s Gospel Experiment

—How do you think Orthodoxy influenced the State and political practice of Kievan Rus’?

—“Influenced” is not the right word. In my view, Orthodoxy actually formed the Russian statehood. The adoption of the Byzantine tradition predetermined all subsequent development—of politics, economy and especially culture.

—The famous historian and theologian Anton Kartashev (1875–1960), speaking about Prince Vladimir’s feasts where he began to invite common people, maintained that the prince was inspired by reading the Gospel—he decided to arrange his principality’s social life according to the Gospel standards. Do you agree with his opinion?

—It’s not that simple. Initially, such feasts were a manifestation of a pagan custom—another thing is that Prince Vladimir “churched” it to some extent. After all, what is a feast? It is informal communication between a prince and his retinue and high state officials, to use modern terms. Thanks to such banquets many important issues were decided, and disagreements and conflicts were overcome. That is, they were an important element in the system of administration that had existed before the Baptism of Russia.

In addition to feasts with the retinue, Prince Vladimir established the tradition of holding feasts with clergy, feasts for the poor and the disabled. Such banquets, among other things, demonstrated the prince’s attitude towards priests and monks, as well as towards the homeless, crippled and helpless people—that is, they indicated certain priorities in State policy. I would emphasize that in addition to feasts for the poor brethren, food was delivered on carts around Kiev to those in need—as we would say now, it was humanitarian aid. Most likely, Prince Vladimir really did it for Christian reasons.

Podol (Kiev). General view. Moscow. Scanned from a postcard from the “Postcard. Universal Postal Union. Russia” series, 1906

Podol (Kiev). General view. Moscow. Scanned from a postcard from the “Postcard. Universal Postal Union. Russia” series, 1906

—Was his socio-Christian experiment successful?

—Since we mentioned Anton Kartashev, I will add that he, like his teacher, the church historian Eugene Golubinsky (1834–1912), themselves asserted that social aid and social work did not take any stable forms in the Russia prior to the Mongol invasion. They emphasized that Ancient Russia knew only the so-called “hand-delivered alms”, when a certain amount was transferred from hand to hand, privately, so that a person in need could subsist. But Kartashev contradicted himself, giving examples of social activity in the pre-Mongol period. It is quite obvious that it was not limited to alms. There were so—called church houses—we don’t know exactly what they were like, but apparently, if we apply modern analogies, they were some kind of social and charitable centers. There are suggestions that there were hospitals, almshouses and hospices as well…

As for the continuity of this policy, under St. Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054), Prince Vladimir’s son, assistance that was provided to those in need was not on a smaller scale at all.

In general, the reign of Prince Vladimir should not be regarded as a unique, casual episode in history, after which everything “resumed its normal course”. It is obvious that the choice of faith was a turning point in the life of the young state and largely determined its future.