Zvonitsa of the Rostov Kremlin

Zvonitsa of the Rostov Kremlin

Bell ringing is not merely a part of church services, but a special language through which the inhabitants of Ancient Rus communicated. It called people to prayer, awakened the city for a feast, warned of danger, and accompanied the people both in joy and in sorrow. In the past, every temple and every city had its own sound—its own rhythm, timbre, and manner of ringing, by which people could discern what was happening without even stepping outside their homes. Rostov the Great became one of the main centers of this art. Here the bells did not simply ring—they were played like a musical instrument, creating genuine “melodies” of ringing. Today, the Rostov peals are not a museum exhibit but a living tradition. By becoming acquainted with them, we not only hear the past but touch the cultural memory that still resounds in the present.

Today the Rostov peals are not a museum exhibit but a living tradition.

A major contribution to the continuation of this tradition was made by recording engineer, laureate of the International “Pure Sound” Prize, sound director of the creative association Artes Mirabiles, Alexei Pogarsky. At the III International Symposium of the academic music recording industry, he spoke about the history of the peals of Rostov, the features of their sound, and unique recordings made by him with a team of experienced bell ringers. The organizer of the event is the Russian Musical Union. The event took place with the support of the Presidential Fund for Cultural Initiatives.

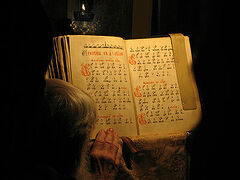

The Rostov bell tower was built in 1689 by Metropolitan Jonah (III) Sysoevich. He loved bell ringing and took a very serious approach to the installation of the bells, their placement, and the construction of sub-bell structures. In 1841, the pilgrim hieromonk Jerome (Sukhanov) was so struck by the local bell ringing that he even made a musical notation for it. It was discovered in 1993 by Alexander Borisovich Nikkanorov. The notation was handmade, and specialists still debate how to properly read this strange score. In 1851, the collector of Russian antiquities Ivan Petrovich Sakharov testified that on the bell tower of the Rostov Dormition Cathedral they rang by notes, in three tunes—the Ionin, Akimov, and Dashkov—although written notes for these have not been found to this day.

A key moment in the history of bell ringing occurred in the nineteenth century when Archpriest Aristarchus Israilev of Rostov, a highly talented self-taught acoustician, devised a method for measuring frequency using a set of handcrafted tuning forks. At that time, Alexander Grigorievich Stoletov even ordered one such specimen from him for the Imperial Moscow University. In 1884, Aristarchus Israilev’s book was published with a detailed description of the Rostov bells and scores of the peals. These are the only surviving pre-revolutionary musical notations of such music to date. In 1919, the Bolsheviks wanted to destroy the unique bells. Then, at the request of the director of the Rostov Kremlin, Dmitry Alekseevich Ushakov, People’s Commissar Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky personally came to the city with a group of scholars and helped save them.

—By the way, Peter the Great at one time also wanted to recast the Rostov bells into cannons, but they bought him off for an enormous sum of money, noted Alexei Pogarsky.

In 1963, sound engineer Alexander Matveenko from the Gorky Film Studio and sound engineers from Mosfilm, Igor Urvantsev and Yuri Mikhailov, made two recordings of the Rostov peals for Sergei Bondarchuk’s film War and Peace, and in 1967 the artistic-documentary film Seven Notes in Silence was released, which tells about different musical genres, including the Rostov bell ringing. Its sound operator was Igor Vidgorchik. In those years, the peals were performed by the then-elderly local bell ringers: Alexander Butylin, Mikhail Uranovsky, Peter Shumilin, and Nicholas Korolev. Alexei Pogarsky emphasizes:

—Thanks to these recordings, according to Alexei, they were able to pass on to us the spirit of the living tradition.

In the subsequent years, regular bell ringing in Rostov was suspended and resumed in 1989. Most of the bells in the bell tower have names, each with its own size: the largest “Syssoy” weighs thirty-two tons, the “Polieley” sixteen tons. Interestingly, the ringer actually stands inside the largest bell, “Syssoy.” The “Swan” weighs eight tons, the “Golodar” (2,700 kg), the “Ram” (1,280 kg), the “Red” (480 kg), the “Goat” (Tikhonovsky) (320 kg), and the “Iofanafovsky” (106 kg). The bell tower also houses four nameless bells and three small ringing bells.

In Rostov the Great, a sound recording has been preserved of those bell ringers who remembered the living pre-revolutionary tradition.

Rostov the Great is the capital of the Russian bell-ringing tradition because it is in this city that a historical set of unique bells has been preserved, the only musical notation of historical peals, and a sound recording of those bell ringers who remembered the living pre-revolutionary tradition. In 2018, at the invitation of the director of the Rostov Kremlin, Natalia Stefanovna Karovskaya, Alexei Pogarsky, together with a specially assembled group of experienced bell ringers, attempted to bring together these three components and carried out a great deal of work. The team included Hierodeacon Roman (Ogryzkov), Konstantin Mishurovsky, Vasily Sadovnikov, Nicholas Samarin, Victor Karovsky, and Olesya Rostovskaya. However, Alexei’s acquaintance with the Rostov bells occurred long before that.

—For the first time I found myself in Rostov the Great in 1986 on a school excursion. They told us about the bell tower, but for some reason we were not allowed to climb it. And I got there again only in 2014. Then I made my first recording in Rostov and discovered an abyss between what I heard on the bell tower and what was on all the recordings without exception. A huge difference between how the bell ringing is heard from below and how it is heard by the bell ringer himself. All the recordings sounded through the ears of the listener, but I wanted them to sound through the ears of the bell ringer. I realized that I wanted to record the bells as a symphony orchestra is recorded, recalls Alexei.

Photo provided by the Russian Musical Union

Photo provided by the Russian Musical Union

At the very beginning of his work, he encountered many difficulties. Recording on general microphones did not give a bright timbre and proper balance, surrounding noises interfered, close cardioid microphones sounded strange and did not solve the timbre problem. It was unclear how to properly position the close microphones and achieve the correct sound balance. At the same time, the sound engineer faced rather serious tasks: to beautifully and authentically convey the sound of large bells, to control the iron overtones of the bells, and to assemble the complex space of the bell tower into a coherent sound picture reminiscent of an orchestra recording.

It was practically impossible to find information on the features of such recording.

—The excellent work of Vadim Kiranov Technology of Recording Bell Peals was published only seven years later—in 2021. At that time, I had only found Peter Kondrashin’s article Practice of Recording Orthodox Services, in which the author briefly and concisely generalizes his personal experience. There one could read very valuable advice, but unfortunately, they were only a small addition to the main topic of the article, says the sound engineer.

In the end, the solution to most problems was “circular” microphones, which he installed in a completely new way.

—From 2016 to 2018, Alexei went on, we came to Rostov the Great for recording no fewer than eighteen times. We searched for positions and types of microphones. We compared, placed them in different ways, and in the end the solution was found, he recalls.

Alexei Pogarsky managed to find the most effective method of recording bell ringing, conveying the full volume and beauty of the sound.

He says that now he records everything on “circular” microphones: piano, organ, choir, ensemble of medieval music and orchestra of Russian folk instruments, symphony orchestra and the St. Petersburg Orchestra of Improvisation. But it was particularly the recording of the Rostov bells that allowed Alexei for the first time to find the most effective recording method, conveying the full volume and beauty of the sound.

—Perhaps after listening to it, you will want to visit Rostov the Great. Go into the Dormition Cathedral and be sure to climb up to the bell tower to feel the spirit of the bells live, said Alexei in conclusion to his talk at the symposium.

In 2019, at the First International Competition of Sound Engineers of the Moscow State Conservatory, his recording of the Rostov peals was awarded a prize.