The following is an extract from the book Archimandrite Seraphim. We are Always Under God's Wing, by Deacon George Malkov (Sretensky Monastery, 2010). It features the recollections of Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov), Superior of the Sretensky Stavropegic Monastery in Moscow, who began his monastic life in the Pskov-Caves Monastery.

* * *

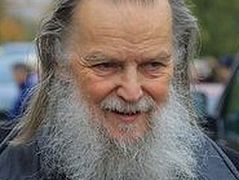

Archimandrite Seraphim (Rosenberg) in front of the Dormition Church, Pskov-Caves Monastery

Archimandrite Seraphim (Rosenberg) in front of the Dormition Church, Pskov-Caves Monastery In general, despite his introverted and austere nature, he was an unusually kind and loving person. Everyone in the monastery boundlessly respected and loved him as well, although they related to him with fear, or rather with awe, as to a man who lived on earth with God—as to a living saint.

I remember my observations of those years. I was the cell attendant of the Father Superior, Archimandrite Gabriel, and noticed that when Fr. Seraphim entered the altar, the Father Superior would quickly rise from his seat to greet him with particular respect. He did not behave that way with anyone else. Every morning, winter and summer, Fr. Seraphim would go out of his cave cell, briefly look around the monastery to see if everything was alright, and then return to his cell to light the wood stove—something that had to be done nearly every day of the year due to the moisture in the cave. I think that he perceived himself as a particular guardian of the monastery, or perhaps he was in fact given this duty. In any case, the voice of this German baron, a great monk, ascetic, and clairvoyant, was always the decisive one for all complex decisions made by the brothers of the monastery.

Fr. Seraphim rarely gave any particular instructions. In the anti-chamber of his austere cave cell hung pages with sayings of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, and those who came to him were often given these citations, or Fr. Seraphim's advice to "read St. Tikhon more often"; and this was enough.

During all his years in the monastery, Fr. Seraphim was always satisfied with the very least—not only of food, but also sleep, contact with other people, and even the most ordinary things. For example, when he went to the banya[1] he would never use the shower, and a small washtub filled with water was enough for him. When the novices would ask him why he did not use the shower—after all, the shower provided all the water one could need—he would answer abruptly that washing under a shower is like eating chocolate.

Once in 1984 I had the opportunity to go to Diveyevo. It was not as simple to go there then as it is now because there was an off-limits military base located nearby. The old Diveyevo nuns gave me a piece of the rock on which St. Seraphim prayed. When I returned to Pechory, I decided to go to Fr. Seraphim and give this holy object to him, since it was something connected with his patron saint. Fr. Seraphim stood silently for a long time and then asked, "What can I do for you in return?"

I was even a little taken aback. "Nothing…" I answered; but then my most treasured desire shot out. "Pray that I would become a monk!"

I remember how attentively Fr. Seraphim looked at me then.

"For that, the most important thing," he said softly, "is your own will that it be so."

He spoke to me about the will for monasticism once again many years later, under completely different circumstances. I was already living in Moscow, under obedience to Vladyka Pitirim. Fr. Seraphim was living out the final year of his earthly life. It seems he was no longer able to rise from his bed. When I came to the monastery, I went to visit the elder in his cave cell. Suddenly he himself began a conversation about monasticism. This was something very unusual for him, and therefore even more precious. I remember several main points from that conversation.

First of all, Fr. Seraphim spoke of the monastery with enormous, inexpressible love, as of a most great treasure:

"You cannot even imagine what a monastery is! It is a… pearl, a wondrous diamond in our world! You will only appreciate and understand this later."

Then he told me about the main problem with monasticism these days: "The trouble with our monasteries today is that people come to them with a weak will."

Only now do I have an increasingly greater understanding of how deep Fr. Seraphim's remark was. Sacrificial self-denial and determination for monastic podvig is decreasing in us. Fr. Seraphim's heart was also aching over this problem, which he observed in the young residents of the monastery.

Finally, he said something that was very important to me: "The time of large monasteries has passed. Now small communities, where the abbot is able to care for the brothers' spiritual life, will bring forth fruits. Remember this. If you become a father superior, do not take in too many monks."

That was our conversation of 1989. I was just a simple novice at the time—not even a monk.

My monastic friends and I had no doubts about Fr. Seraphim's clairvoyance. Fr. Seraphim's own reaction to any talk of miracles and clairvoyance was very sober and even skeptical. Once he said:

"Well, everyone says that Fr. Simeon was a miracle worker and clairvoyant. But as long as I lived near him, I never noticed anything. He was just a good monk.

But I experienced the power of Fr. Seraphim's gift more than once.

In summer of 1986, I walked by the elder's cell and saw that he was getting ready to replace the light bulb on his porch. I walked over to him, brought a stool, and helped him screw in the bulb. Fr. Seraphim thanked me and said, "One novice was taken to Moscow by a hierarch on obedience. They thought that it would not be for long, but he remained there!"

"So?" I aksed.

"That's all!" said Fr. Seraphim, then turned around and went into his cell.

I went about my work perplexed. What novice? What hierarch?...

Three months later, Father Superior Archimandrite Gabriel summoned me. He said that Archbishop Pitirim of Volokolamsk, the head of the Moscow Patriarchate Publishing department, had called him that day from the capital city. Vladyka Pitirim had learned that there was a novice in the Pskov-Caves monastery with a degree in cinematography, and asked the Superior to send him to Moscow: they needed specialists right away to prepare television and cinema programs for the celebration of the 1000 years of the Baptism of Russia, which would take place in two years. I was the novice he was talking about. It seems to me that this was the most horrible day of my life. I begged Fr. Gabriel not to send me to Moscow, but he had already decided.

"I am not going to fight with Pitirim over you!" he said, cutting off all my pleas.

Only later did I learn that my return to Moscow was also the long-standing request of my own mother, who hoped to talk me out of monasticism. Fr. Gabriel felt very sorry for her and was only waiting for an excuse to send me back to my inconsolable parent. Iron-clad formulations were part of his normal style.

Of course, I immediately recalled my last conversation with Fr. Seraphim about the novice, about the hierarch, and Moscow, and I ran to his cell.

"It's God's will! Don't be sad. It's all for the better. You yourself will see and understand," the elder said to me affectionately.

How difficult it was at first to live again in Moscow. It was hard precisely because I would wake up at night and understand that the amazing monastery, incomparable to anything else in the world, with people like Fr. Seraphim, Fr. John, Fr. Nathaniel, Fr. Melchizedek, and Fr. Alexander, was hundreds of miles away; and I am here in this Moscow, where there is nothing like it at all!

[1] The monastery would have "banya" day once a week, when the Russian-style steam bath would be stoked.