ST. ANDREW’S MARTYRDOM

From Epirus he went to Thessaly, to Lamia, then to Loutraki-Corinth. His cave in Loutraki can still be seen. From Corinth he went to Patras where he stayed a year or two, preaching in the Peloponnese. We also have local traditions that he went to the small island of Galaxidi, off of the Peloponnese. Finally, he was martyred at Patras at an extremely old age.

Something else that I understand from these traditions is that it is impossible that St. Andrew was martyred in the times of Nero. We have two Greek traditions; one placing his martyrdom under Nero, and the other under Domitian or at the beginning of Trajan’s rule in the early second century. I think this last one is right. The Romanian tradition says this also, and if you follow the sources this is what fits.

In St. Gregory of Tours’ version of the “Acts of Andrew,” it says that before his martyrdom, St. Andrew had a dream in which he saw his brother Peter and John the Evangelist in Paradise. He saw them in Paradise before his martyrdom. So, this could be an indirect reference to the fact that St. Peter and St. John had already passed on. St. Epiphanius also says this, as does Pseudo-Abdia, the bishop of Babylon (or the historian who wrote in his name). If this is so, it places his repose after St. John’s.

According to the scriptures, St. Andrew would have been younger than his brother Peter, because in the scriptures the name of St. Peter comes first, then Andrew. In the texts of civilized societies, the elder is always mentioned first, then the younger. But then the question arises, if he was younger, why in icons do we depict St. Andrew as much older than Peter, an old man in fact? Even Da Vinci did so in The Last Supper and he had taken his representation from earlier icons. In Sinai, at St. Catherine’s Monastery, where we have some of the earliest icons in existence, St. Andrew is also depicted as old. This is because in iconography we make the icon of the person as we last saw him, and they remembered the older Andrew.

Only St. John is not depicted as an old man, because he was blessed by the Lord to “tarry until I come,” but the other apostles are always portrayed at the age of their death, as is the Lord Himself.

ST. ANDREW, THE MAN AND APOSTLE

RTE: Tell us now about St. Andrew himself. What have you learned about him?

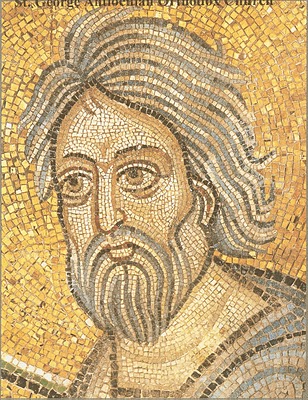

Apostle Andrew, mosaic.

Apostle Andrew, mosaic.

RTE: Do you mean strange or unique?

GEORGE: Unique, but strange as well. He had a habit of putting up big stone or iron crosses everywhere. He carried a huge staff with a cross. He was modest, he didn’t make a lot of disciples – just a few, in a few small circles. He didn’t preach to huge crowds like Peter or Paul. St. Andrew gathered small companies, as would a geronda or a staretz.

Also, he had a sense of humor. For example, some of the sources say that when he first saw the saunas of the Slavs in what is now Novgorod he wrote letters to friends saying, “These Slavs are such strange people; they torture themselves with birch branches.” He was laughing about it. You cannot imagine him as a master of strictness. He was a humorous man, very humble, very easy. As a Mediterranean person he was surprised by these strange traditions. Of course, he was also a man who had seen many things. He traveled with Lapp reindeer herders, with Huns, spoke to Greek philosophers, Russian merchants, knew Chinese bureaucrats, visited primitive tribes in northern Pakistan and Berbers in the deserts of the Sahara.

You can understand from this how much he knew and how great his store of practical wisdom must have been. Not only grace-filled wisdom from the Lord, but his worldly wisdom. Because he was humble, he could speak to all these people. He was not an invader, he was not an explorer, he lived as one of them. He fished with them, ate with them, farmed with them, traveled with them – by any means they had – on foot, by canoes or boats, horses, camels, reindeer, elephants. You can imagine what he must have seen.

The important thing is that because he was humble he shared their experience. If you aren’t humble, you cannot share another person’s experience, you can only report about them, but he was their equal and he gained their wisdom, and they gained his.

Apostle Andrew was so modest that he didn’t step forward with the triad of Peter, James, and John, although he was the “first-called.” The first-called, but he never went first. He only went first when he had something to ask from God. We have three examples of this from the gospels. One was on Holy Thursday when the Lord went to the temple, “there were certain Greeks among them that came to worship at the feast.” These Greeks came to Philip and asked if they could see Jesus. Philip didn’t know what to do with them so he told Andrew, and Andrew took him and went to the Lord.

He was not afraid to face God, and he knew Christ was God, he was the first to understand and follow him. He was also the first missionary, to his brother Peter. The second time is the miracle of the five loaves and the two fish. Andrew was the one who went to the Lord and said, “We have this problem. Aren’t you going to do something?” He was never in the forefront for himself, but when it was for other people, he demanded help from God. The third time was in the Gospel of St. Mark, where, with Peter, James, and John, Andrew asked the Lord about the signs of the end times.

In these old traditions from the second and third century, Andrew was so humble that he thought everyone he met was Christ Himself – the captain of the boat, the peddler on the dock. The apostles didn’t have the arrogance of the Greco-Romans, or even of the Jews. They were very humble people and could meet both barbarians and Greek philosophers. We know that the Apostle Andrew was not against Greek philosophy. He liked to speak to philosophers and he even had as a disciple the Greek mathematician and philosopher Stratocles, the first bishop of Patras. Stratocles was probably a former Pythagorean, because the Pythagoreans had connected mathematics and philosophy with a unique mysticism. This is the secret, I think, to understanding St. Andrew’s soul, that he was very modest and that he saw everyone as an icon of Christ.

RTE: Yes. Where else was St. Andrew persecuted?

GEORGE: Coptic tradition says that he was persecuted in the Land of Anthropofagi (almost the only “uncivilized” place where we know he was badly treated). He was also persecuted in Kurdistan and Arab legends say that he died there. If this story is substantially true, I believe that his persecutors left him for dead, but that his great physical strength allowed him to recover and he left secretly, perhaps to protect disciples who remained behind.

He was persecuted again in Sinope of Pontus, in Thessalonica, and later in Chalandritsa near Patras. In Thessalonica, the Roman rulers put him into the arena with wild animals, but one thing that is very good for my conscience as a Greek is that during all of his persecutions the local Greeks defended him. In Thessalonica, a huge uprising stopped the persecution and the Romans were forced to take him from the arena.

You can explain this persecution in the Greco-Roman world, you know. The Christian belief was not an easy belief. We can’t understand today what it meant to put men, women, slaves, nobles, Jews (even Pharisees), barbarians, the sick, educated scholars, and former pagan priests at the same table, and even to allow intermarriage between them. It was against the norms of the whole society.

RTE: How old was St. Andrew when he was martyred in Patras?

GEORGE: From the Romanian traditions, which I take as the most reliable, he was more than 85, perhaps even 95. We believe he was martyred between 95 A.D. and 105 A.D. Because of the dream he had of St. John the Evangelist in heaven, it was perhaps after St. John’s mysterious repose in Ephesus (you remember, the Greek tradition says that he was buried alive to his neck and then his body simply disappeared), which would make it 102 or 103 A.D. under Emperor Trajan, not Domitian as is often thought. In fact, there are still folk songs in Romania that speak of a meeting between Emperor Trajan and St. Andrew.

St. Andrew is exceptional, someone unique. He allowed himself to be crucified at a very old age. He easily could have avoided death if he had just told Maximillia, the Roman proconsul’s wife, to return to her husband. But he wouldn’t violate truth, so Aegeates, the proconsul, had him condemned. After he was crucified, a huge Christian crowd marched on Aegeates’ palace and he was forced to order St. Andrew’s reprieve, but the soldiers couldn’t touch the apostle because St. Andrew himself wouldn’t allow it.

St. Andrew was against the sovereignty of this world. He was a disciple of St. John the Baptist and he refused to compromise. If he had felt that Aegeates really regretted what he had done, he would have come down from the cross, but he didn’t want to do a favor for a man who would use his rescue for his own political benefit. He wasn’t a strange man who wanted to die on a cross, but what he wanted more was to love Aegeates and to be loved by Aegeates in a Christian manner.

It was a confrontation with the evil of the time and St. Andrew was fighting the devil himself through this. He did not love martyrdom, he was fighting for his Christ and that was the most important thing.

RTE: What happened to his relics? Weren’t they eventually taken to Constantinople?

GEORGE: Yes, they were in Patras for several centuries and then were taken, along with St. Luke’s relics in Thiva, to Constantinople in 357 by the Byzantine commander-in-chief, Artemius,[1] to be put in the Church of the Holy Apostles. St. Andrew’s head was left in Patras. This is the same period in which St. Regulus traditionally took a small portion of the relics to Scotland.

After the sack of Constantinople, the Crusaders took the relics to Amalfi, Italy, but St. Andrew’s head remained in Patras until the 15th century when it was given to the Roman pope by the last rulers of Patras before the Turkish occupation. The Catholic Church returned it to the Orthodox in Patras in 1964, and it is now in the new Orthodox cathedral dedicated to St. Andrew, enshrined in a silver mitre. The old cathedral next to it still has the older sepulchre although all the relics were removed from it long ago.

His relics were scattered, but there are still a few small pieces in Amalfi. In 1969, the Pope took some to the new Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Mary in Edinburgh. Also, one foot of St. Andrew is enshrined on the island of Cephalonia (off the Peloponnese) in St. Andrew’s Monastery and there is a small piece of the front of his skull in the Skete of St. Andrew on Mt. Athos.

The cross of St. Andrew was taken from Greece during the Crusades by the Duke of Burgandy, and returned to the Orthodox cathedral in Patras in 1968 from the Church of St. Victor in Marseilles.

RTE: Perhaps because they are so geographically close, the Greeks and Romans seem to have been tied together throughout history. Aren’t there descendants of Byzantine Greeks still living in southern Italy? Could they have known St. Andrew?

GEORGE: Yes. In southern Italy we have both Greeks and descendants of proto-Bulgars from the Russian steppes who came to Greece. There is also a possibility that St. Andrew went to Calabria in southern Italy. There is a very old village there called San Andrea, Apostolo D’Ionio, “St. Andrew, Apostle of the Ionian Sea.” We have an unusually large number of churches dedicated to St. Andrew in this place and it was only two days by boat to southern Italy over the Ionian. It is mentioned twice by St. Gregory of Tours, that Stratocles, the first bishop of Patras and a disciple of St. Andrew, was from Italy. There is also an old tradition that St. Andrew resurrected people who died in a shipwreck coming from Italy to see him in Patras. He prayed and they came back to life. So, there seems to be a good possibility that Stratocles, if not Andrew

himself, had connections with Calabria.

RTE: You’ve spent time in these villages in southern Italy, haven’t you?

GEORGE: Yes, and this is part of my own story. A close friend of mine, Antonio Mauro, is from the Greek-speaking region of southern Italy and for many years was an atheist and far left-wing fighter for human rights. I lived with him in Bova Marina and we shared many nice times. He was an atheist and I was Orthodox, but we traveled together very often and even covered the war in Serbia together, me as a journalist and he as a foreign observer.

Several years ago, long before I started this book, we were on our way to Athens when he said, “Let’s go to Thessalonica instead.” We went to Thessalonica and he said, “Georgio, what do you think? Do you want to baptize me? Let’s go to Mount Athos.” So we went to Mount Athos and a lot of strange things happened, like losing the once-a-day bus from Daphne to Karyes. There was no one else on the road so we had to walk on a very hot, difficult day. Finally, a man picked us up who had known me when I was the director of TV news in Cyprus. He was the brother of the hegumen (abbot) of Vatopedi, and took us to the monastery. The hegumen welcomed us warmly and when we said that Antonio wanted to be baptized, he told us that in this monastery there happens to be a monk, Fr. Dimitrios, who catechizes Italians in Italian.

Many things happened at Vatopedi, small miracles, but the most important of them was that after his baptism Antonio went to his room to lay down. In the meantime, as his godfather, I went downstairs to buy him a small gift. I wanted to give him an icon of St. Anthony, but the man said, “We don’t have St. Anthony, take St. Andrew.” So I bought St. Andrew, and when I came back I saw Antonio looking sick, and I said, “What happened?” He said, “Nothing.” I gave him the icon and when he saw it he began to cry. He told me, “I’ve just seen this man in front of me on the wall, alive, and he told me, ‘Antonio, you must fight,’ and I said to him, ‘My father, I’ve been fighting all my life.’ Then he said again, ‘You must be strong and fight.’” You see, Antonio didn’t know if he would do alright after being baptized. He was feeling very good but he had some doubts. When he saw the figure on the wall, he thought it was his imagination, but then he saw the icon, exactly the same image, and he knew that something incredible had happened.

Later, I bought a small piece of land in Bova Marina and once, when Antonio was working there, he saw St. Andrew with a huge staff. He didn’t know that St. Andrew carried a staff, but all of the traditions speak of him as carrying a great staff. He only saw him for a few moments, but he was shocked because it was the living image of the same person he had seen on the wall. When I came, he told me the story.

A little later, by chance, I bought a book about the local history of Bova Marina. We were amazed when we read there that several centuries ago Catholics had taken small pieces of relics of St. Andrew from the Orthodox Church of Bova and thrown them into the fields. (We had no idea that St. Andrew’s relics had ever been there.) The Catholics did this because St. Andrew is the patron saint of Constantinople and they wanted to cut the ties between Constantinople and this Greek-speaking area of southern Italy so that people would become Catholic. No one knows where they threw the relics. It could have been in any of the fields around the village.

RTE: Perhaps it was even your own field.

GEORGE: Yes, perhaps. Only God knows.

RTE: Do you feel close to St. Andrew?

GEORGE: Sometimes he is very close. I often have impressions to look up things I would never have thought of on my own, and almost always find missing pieces or new evidence.

As I was researching this book a very close relative of mine had a dream in which she saw a monk we know from Valaamo Monastery in Finland with the abbot of Valaamo. My relative was surprised because the abbot of Valaamo in her dream was a very different man from Igumen Sergei. He was a big man with a large nose, very tall. I had been working on the book, but had told her nothing about St. Andrew’s looks, but the man in her dream fit precisely with the descriptions of the apostle in all the early traditions. The most incredible thing, though, is that in her dream this man was the abbot of Valaamo, but she saw him in Sebastopol of the Crimea (the ancient Cherson) and she knew (as you know things in dreams) that he was also the Metropolitan of Thrace. What she had no idea of at the time was that St. Andrew was the enlightener of Thrace, that he had been in Sebastopol-Cherson, and you might say that he was the abbot of Valaamo because he first brought Christianity there.

Of course, all of this could be coincidence, but the thing that makes me believe this was more than a dream is that when I called our monk-friend in Valaamo to tell him about the dream, the monks told me that he had recently left for the Skete of St. Andrew on Mt. Athos!

RTE: Wonderful. What do the early sources say St. Andrew looked like?

GEORGE: In all the world traditions, and in the book by Max Bonnet,[2] who did a commentary on the “Acts of Andrew” by St. Gregory of Tours, he is described as being very tall, a bit stooped, with bushy eyebrows that meet over a large nose, curly hair and a beard that is mixed black and grey and which separates into two parts at the bottom. In her dream, my relative saw him with blue eyes, short-necked and very, very strong. We know he would have had to have been strong because he traveled and lived in very difficult places. He went from -40 C. in Valaamo and the Caucuses to +50 C. in the deserts of the Middle East and Central Asia. You can imagine what kind of a man he was. You can even see this in his martyrdom. He was crucified for three days, but still couldn’t die, although he was very old.

RTE: How has your feeling for St. Andrew changed since you began writing about his journeys, and how has the book changed you?

GEORGE: I’m still a sinner. Nothing can change me. I’m just very happy that I’m writing this book and I’m also very shy about it. I want to write it and at the same time I want to avoid writing it, because this is a high obligation and I’m afraid. It’s something I am obliged to do, and when it’s finished I will leave it quickly because it’s too much for me.

RTE: Like Peter saying, “Lord, let us put up three tents.”

GEORGE: Yes, like this. I’ve been thrilled by St. Andrew’s life. He was so humble, so completely unimportant socially, but he was the first man on earth called by Christ Himself to be His disciple. What was it that the Divine eyes saw in his soul? He had an exceptional soul because God Himself came to him. If Mother Mary is for the women, then St. Andrew is for the men.

Reprinted with permission from

The Road to Emmaus

My sincere thanks for the long hours and hard work that produced this research.