Nun Seraphima after long years in a concentration camp.

Nun Seraphima after long years in a concentration camp.

Mother Seraphima had a sensitive style and artistic nature, and was able to recreate in a lively way those events that she herself witnessed; she held all the Diveyevo traditions sacred, and became a treasure house of those precious examples of God's special Providence. Born in Moscow, she lived in the village of Vyezdny near Diveyevo after it closed, and received many pilgrims to that holy place, consoling them and conducting edifying discussions. Her memory is lovingly preserved by all who had the opportunity to meet her.

The second, Schemanun Margarita, is still alive at the time of this writing. She is now ninety‑eight years old.[2] Schemanun Margarita is a living link between pre‑revolutionary and modern Diveyevo Convent. As was foretold to her by Blessed Maria Ivanovna, the Diveyevo fool‑for‑Christ, Mother Margarita would be the only sister who would live to see the revival of this citadel of women's monasticism. She is known for her straightforward, simple‑hearted character, her ascetical independence, her piety and her prayerful yearning for eternity. Her account at the end of this account was written down from her own words.[3]

* * *

In Diveyevo a plan was preserved that was drawn by Fr. Seraphim. According to his prophecy, at the end of time the Monastery would be spread out as far as the shores of the Vichkenzy River (now it is a pond), and the Kazan church as well as the parish priests' houses would be within the monastery walls. That is why the stone wall that surrounds the Monastery was built only to the north, east and south, while to the west was only a simple wooden fence. After the revolution this fence was torn down and a bazaar was held on the Monastery's territory every Monday, which disturbed the life of the Monastery. Several monastic quarters in that area were taken away and occupied during that time.

The monastery was always divided between the old and the new sections. The old monastery began with Mother Alexandra's quarters and occupies the entire northwestern portion; there the monastery garden was located, and beside the new buildings was a little old building where Blessed Pelagea Ivanovna labored in asceticism. Her cell was preserved as it was during her lifetime. A perpetual Psalter reading was carried out there—twelve elder sisters read by turns day and night. This building was called “Blessed Pelagea's hermitage.” Over Mother Alexandra's cell was built an encasement, which formed a second story. Here lived the sisters who took care of the First Abbess' quarters and the Nativity Churches, where perpetual candles were kept (in the upper church) and a perpetual lampada (in the lower church). In the lower church of the Nativity of the Theotokos the Psalter was read perpetually,[4] and only interrupted from Wednesday of Passion Week until after Small Vespers on Saturday of Bright Week.

The hermitage of Blessed Natalia Ivanovna[5] was located in the center of the Monastery, at the end of the Canal. The hermitage was preserved as it was during the blessed one's life, and the Psalter was read perpetually there also. The Psalter was also read perpetually in St. Seraphim's near hermitage, which had been brought from the Sarov forest (near the spring). An encasement was built which contained the log frame. Blessed Prascovia Ivanovna’s cell was also preserved, and the Psalter was read there night and day by designated sisters. In Mother Alexandra's cell the Psalter was read by twelve sisters.

All of these preserved quarters were called “hermitages.” Pilgrims were taken to them and the sisters often visited them, especially on feast days. On Forgiveness Sunday, after Vespers, as well as on Pascha and Christmas and other great feasts, the sisters would visit without fail all of the hermitages and graves of the righteous ones—Mother Alexandra, Schemanun Martha, Elena Vasileevna Manturova and the God‑pleaser's servant, Motovilov (located near the Kazan church).

An altar was made out of logs from the Far Hermitage [of St. Seraphim] for the cemetery church of the Transfiguration. The Saint' personal possessions were kept there in a special glass case.

There were nine churches in the Monastery:

1. The warm cathedral of the Holy Trinity with side altars to the Umilenie Icon of the Mother of God, and to St. Seraphim. There were also two more side altars there, one to the Vladimir Mother of God, and another to St. John the Baptist.

2. The wooden Tikvin church (built by John Tikhonov) with side‑altars to All Saints and Archangel Michael.

3. Under the Tikhvin church was a church dedicated to the icon of the Mother of God called “Assuage my Sorrow.” After the monastery was closed they built a mill there, and in the fall of 1928, the church burned down.

4. In the cemetery was the church of the Transfiguration.

5. In the almshouse (which is what they called the old hospital) was a house church named for the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow.” The main entrance to it was on the Canal side, and to the north and south were doors to the corridors. In two cells that adjoined the altar were windows, so that the infirm, elderly sisters could pray right there in their cells. The last service in this church took place on the Feast of the Exultation of the Cross in 1927, when the sisters bade farewell to one another.

6. In the abbatial quarters was a house church dedicated to the Equal‑to‑the‑Apostles, Mary Magdalene. His Majesty Nicholas Alexandrovich requested a Liturgy there. He even asked specifically for a priest that would serve reverently and not hastily, but who would complete the service in one hour. The Abbess assigned Fr. Peter Sokolov, who was the youngest priest at that time. He had a good voice, precise diction, and a lively, quick character. Fr. Peter's service pleased the Tsar very much. At the end, he called this priest to himself and awarded him a gold cross with precious stones. They say that when Fr. Peter went to the Tsar he became flustered and fell at his feet, but the Annointed of God lifted him up, sat him down next to himself and turned to the Over‑Procurator of the Holy Synod saying: “This is an excellent, reverential servant of the Church of Christ,” and with these words placed a cross on his neck.

7. Additionally, there was a church in the Trapeza dedicated to Grand Prince Alexander Nevsky. There they served mostly in winter, because the Tikhvin church was crowded and stuffy. Earlier there was a village cemetery on this spot. The cemetery was moved away from the Monastery buildings, closer to Sarov. The Convent's cemetery occupied the southeast corner of the Canal, situated around the Church of the Transfiguration.

The Kazan Church.

The Kazan Church.

That makes nine churches and fifteen altars. On every patronal feast, a Paraclesis to the Mother of God was served during Small Vespers, and in the morning there would be a blessing of the waters. On the patronal feast of the Umilenie Mother of God, July 28, and on St. Seraphim's day, July 19 and January 2, as well as on the day the Convent was founded, December 9, the feast of the Conception of St. Anna, there would always be a procession along the canal after the late Liturgy, with the singing of the Paraclesis to the Mother of God “Who upholds many.” On the eve of December 9, there would be a solemn All‑night Vigil for the feast of the Umilenie Mother of God and St. Seraphim. An Akathist would be read, half to the Annunciation of the Mother of God and half to St. Seraphim. There is a special service to the Umilenie Mother of God composed by Metropolitan Seraphim Chichagov. On the feast of the Mother of God, “The Life‑giving Spring,” there would be a procession around the Convent along the Canal, and on the other side, around the Convent, outside the wall.

The Monastery clergy were almost all descendants of Fr. Vasily Sadovsky. At the time of the expulsion, the oldest priest was Archpriest Fr. John Smirnov, the nephew of Fr. Vasily (he died in deep old age in Diveyevo). Besides him were: Fr. Michael Gusev, the son of Fr. Vasily's granddaughter, whom Fr. Vasily had raised (Fr Vasily died in prison); Fr. John Polidorsky, the husband of Fr. Michael's sister (he died in Solovki).

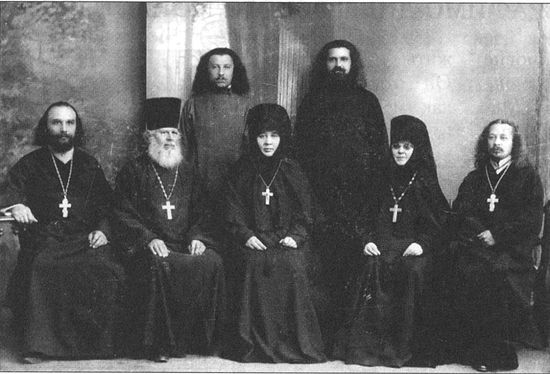

The Monastery clergy at the beginning of the 20th century. From left to right: Fr. John Polidorsky, Fr. John Smirnov, Abbess Alexandra (Trakovskaya), treasurer Mother Liudmila, Fr. Michael Gusev. Standing: Deacon Senatsky and deacon Sokolov.

The Monastery clergy at the beginning of the 20th century. From left to right: Fr. John Polidorsky, Fr. John Smirnov, Abbess Alexandra (Trakovskaya), treasurer Mother Liudmila, Fr. Michael Gusev. Standing: Deacon Senatsky and deacon Sokolov.

During Great Lent the services began at four in the morning: Morning Prayers, Midnight Office, Matins, the hours and the Liturgy of the Pre‑sanctified Gifts. At 3:00 p.m. during the first week and at 4:00 p.m. during the rest of the fast, Great Compline was read with a canon, then an Akathist, and the usual rule. The spiritual readings came after Compline.

Sisters who shared a building always read the evening prayers together. After Liturgy, molebens and pannikhidas were served; the priests went daily to serve pannikhidas in all the hermitages, while in the Near Hermitage a moleben was served. On Sunday evening they always sang an Akathist to St. Seraphim in place of the second kathisma at Matins. Some people have seen how the Saint covered the choir with his mantle during the Akathist.

The choir sisters were divided into two cliroses—the right and the left. Each choir occupied a special building. The right cliros always sang at the late Liturgy, and the left cliros sang at the early Liturgy. Both choirs sang during Vespers and Matins (as well as All‑night Vigil) on two cliroses. At certain times, the two choirs joined. On weekdays each choir was further divided into two groups. One half began the week and the other finished it, each singing for three consecutive days.

The service was always sung with a canonarch.[6] The altos read and served as canonarchs. The bass singers read only the Epistles and the six psalms. The sopranos did not read at all.

During Vigils, the choirs came together at the ambo to sing katavasia. Both choirs read, each reading every other week.

After Morning and Evening Prayers the short rule of St. Seraphim was always read. In the evening everyone walked along the Canal and read the prayer “Rejoice O Virgin Theotokos” [7] one hundred fifty times, saying the “Our Father” at every tenth with a commemoration of the living and the dead. On October 1, the feast of the Protection of the Mother of God, in the evening after Matins, the entire Monastery prayed one hundred fifty times in the church. They also prayed in the monastic quarters for the living and the dead, and at all times of need. This was the most widely used common rule.

On the twelve great feasts, the zealous would gather to pray all night in the church. On the feast of Theophany[8] they always placed an urn of water in the middle of the church, and when they prayed just before midnight they always saw that the water would sort of boil for a moment. They also gathered to pray before the Royal Doors on Bright Saturday from the end of Liturgy until Small Vespers.

Only young virgins sang on the cliros and worked in the church.

There were very many different monastic building quarters in the Monastery; it seems there were about sixty-six—a few partially built of stone, the rest wooden. Until the ‘sixties one building was preserved that had been built during St. Seraphim’s time—the first trapeza.

The sisters lived in quarters according to their obediences. The buildings usually contained the living quarters as well as the workshops. One worked were one lived. The Monastery had a large icon painting studio. There the sisters not only painted icons, but also gilded and engraved. Each sister had her own specialty.

During the latter times they created a separate iconographic studio.

More than eighty sisters lived and worked in the lithographic quarters. They engraved the stone plates themselves, taking as long as a year to prepare one stone. They printed the pictures on the press, and they dried them. Besides this, they transferred the pictures to white primed boards and then painted them. They poured figures of St. Seraphim feeding the bear on alabaster and painted them. They made various baskets and toys. All of this was given away or sold in the Monastery shop.

Boards were prepared by the carpenters in their workshop near the horse stables, and in the painting workshop they primed the boards and canvases.

In the handicraft workshops they satin-stitched on embroidery hoops and did embroidery in general. In the sewing workshop, clothes were sown for the sisters. There were only a few tailors. In the vestry they sewed and repaired vestments, made flowers, repaired icons and wove Russian lace on bobbins. In the knitting workshop they knit on machines. In the textile workshop was fabric woven from Russian lamb’s wool, which they used to make ryassas and mantles. There were special sisters who sewed apostolniks and kamilavkas.[9]

In the bread bakery the sisters baked bread. The sisters ground their own flour at the mill. Two sisters resided near the mill. Prosphora was baked in the prosphora bakery. The trapeza was contained within the Alexander Nevsky church, and under the trapeza was a kitchen where food was prepared.

In the candle making quarters within the Monastery the sisters made candles, but the wax was prepared, washed, boiled and bleached in the woods of the Lomovka, where there was a special candle-making workshop.

The cathedral guardians lived in a separate building. They had to keep watch over the cathedral in turns. The rest of the ecclesiarchs[10] lived next to their respective churches.

In the cellar building lived the cellarers. Under the building was a large root cellar where they kept the cabbage, cucumbers and mushrooms.

The kvass kitchen was separate. There they made the kvass,[11] then stored it in a cellar under the building. At the end of winter, in March, all the cellars were stuffed with snow and ice.

The Monastery had its own large hospital and pharmacy. The doctors were sisters of the monastery. They also received and treated local peasants. They had their own dental office. The sisters also performed the dentistry. There were four dentists. They not only treated teeth, but also prepared prosthesis.

The orchard-keepers lived in the orchard. The orchard was located in the northeast corner of the Monastery, and in the southeast corner was the dairy, where the milkmaids lived. There was a special water pump there. The main water pump was located at the beginning of the Canal. Everyone took water from there, and some sisters worked maintaining the pipes. There were also sisters assigned to the water pump.

In the milling quarters, the sisters milled in the winter and stored the grain and straw. In the summertime they worked in the fields. The Monastery land stretched out on the southern side as far as the village of Ruzanovo.

The gardeners lived in the gardening quarters.

Unlike the specialists and cliros sisters, the laboring sisters did not live at the place of their labor.

The steward [blagochinnaya] and her assistant oversaw this sort of labor. She assigned work to sisters in the monastery, and in summer sent sisters from all obediences to cut hay, water cucumbers, gather wheat, dig potatoes, collect mushrooms in the woods, and in general to do all the work inside and outside the monastery. Mainly the young ones did all the hard labor. Before the war [World War I] in 1914, hired peasant men cut hay, but after the war the sisters did it themselves.

Hired laborers lived in the horse stables. Various workshops were located there—harness making, metal work, carpentry, and tinsmith. The monastery horses were kept in the stables. The coachmen and stable-hands lived there. Behind the monastery was the monastery brick factory.

There were two shops in the Monastery: one for icons and another for groceries and manufactured items. The sisters could obtain anything they needed without leaving the monastery enclosure. There was a separate shop building, where the shopkeeper-sisters lived.

Thus, the Monastery completely supported itself. Everything could be found within the community. It was a vast, complex, and well-organized economy. The monastery had no capital—it lived by its own labor. The farms and metochions[12] brought their own meager aid, for apart from the young laboring sisters there were many elderly and infirm. Whoever of these elderly was able would read the Psalter in the hermitages, but some were not even able to do that.

Gatekeepers lived at the monastery gates; they watched who went in or out, and locked the gates at night.

The monastery had its own bathhouse.

The Abbess lived in the Abbess’ building. The chancery was in that building. All the monastery accounting was kept there. The storehouse keepers, who kept track of all the goods and produce in the storage, also lived there, as did the postal workers, who gathered and distributed the letters, packages and money to all the other living quarters.

Near the gates, outside the Monastery on the Sarov road, were guesthouses for pilgrims, and further on were the priest’s houses. The guest houses were also run by the sisters.

The orphanage.

The orphanage.

The elderly sisters lived in the almshouse, which was the old hospital. There were two buildings there that were joined by a walkway (on the second floor), so that it would be more convenient to go to the “Joy of All Who Sorrow” church without going outside. Otherwise, many older sisters lived in the bread bakery and other smaller buildings spread throughout the monastery. Whoever had the strength would perform the Psalter reading obedience, reading two hours per day in specific hermitages.

The hermitages and readers were supervised by the monastery treasurer. She kept an account, received lists of names for eternal and temporary commemoration of the living and the dead. The commemoration books were maintained there. Every sister had the right to enter five names of their relatives into the eternal commemoration (at the Psalter reading). Beyond this, each had a card with the names of reposed relatives for whom a separate prosphora was taken each day at the Liturgy. The sisters’ cards and generally all the commemoration books were read by special acolyte nuns. They read and served as acolytes.

The St. Petersburg Metochion.

The St. Petersburg Metochion.

The Monastery also had a number of farms:

1. In Sivukha, not far from the Orans Monastery;

2. In Satis, on the Satis River, was a dairy farm, hay barn and apiary.

3. In Polki, in the forest, seven miles away along the road to Lomasov.

The metochion churches had their own priests and services were conducted daily with a choir of local sisters. They also went to read the Psalter over the reposed. During free time away from services the sisters sewed blankets and knit scarves. In Peterhof was an iconography studio. Almost every metochion had a prosphora bakery. At specific times in the metochions and churches the monastery rule was read.

All the agriculture work was done on the farms—dairies, apiaries, collecting mushrooms and berries for the Monastery. A mile and a half from the Monastery, in the woods by the Lomov river there was a laundry where the monastery laundry was washed.

In Sivukha the sisters went to Orans Monastery on feast days, because it was very close. In Satis they went to Sarov.

No one went to work on Saturdays. It was considered their “own day” when the sisters could earn some money, for the monastery only provided living quarters and a meager trapeza. Each sister obtained her own clothing and shoes, and whoever did not receive some help from her relatives had to earn the money for these things herself. They knit scarves or decorated them, and made prayer ropes, if they knew how. They worked in the evenings in their cells. After a sister died her things were given to other sisters, but mostly to the older ones—apparently they did not put much hope in the younger ones, for not everyone lasted in the monastery.

During the final years, when the Monday bazaar was instituted [by the Communists], the sisters’ “own day” was changed to Monday. In addition to this the sisters were allowed to go out for a month in summer to harvest, for there was no longer even a trapeza.

It is notable that in the Monastery lived many family lines. Thus up until the very expulsion there lived “Meliukovas,” “Putkovas” and other descendants of Diveyevo eldresses.

Obedience was considered the main thing in the monastery. It was placed higher than fasting and prayer. In olden times there existed a specific quota of nuns, and therefore many sisters who wished to be tonsured beyond the quota were secretly tonsured. The dying were also tonsured secretly. Those secretly tonsured bore their monastic names secretly and did not have the right to wear the mantle—they were tonsured in half-mantles. Several years before the expulsion there was a huge stavrophore tonsure ceremony. Many elderly sisters were tonsured (its seems there were two hundred souls, if not more.)

The nuns were obligated to attend monastic services every day, as well as to read three kathismas of the Psalter in their cells. Neither were the younger ones freed from their obediences. The tonsure was not granted to anyone under forty years of age.

Upon entering the monastery the novice wore her lay clothing for a time. After a few months, usually before some feast, the Abbess clothed the novices herself in her quarters—they were given an informal ryassa, apostolnik, a velvet “bare” kamilavka as they called it; and a prayer rope was put into their hands with the commandment to say the Jesus prayer without ceasing. They came to the Abbess in a black sarafan, made in the monastery style, and a monastery blouse.

After a while came the ryassaphore tonsure. It was performed in the church by a hieromonk. The sisters went to the tonsure in pairs, wearing black podrasniks and leather belts, with their hair uncovered.

Then they were given a ryassa with wide sleeves, an apostolnik and a kamilavka, now covered with a veil made of tule. Prayer ropes and lit candles were put into their hands. They saved these candles, which were to be placed in their hands as they lay on their death bed, then put in the coffin with them after death.

During the final years the Abbess clothed them in the kamilavka with the veil right away. The stavrophore nuns, like the Sarov monks, wore ryassas with narrow sleeves. The monastery also had schemanuns and recluses; however there were few sisters who decided to take the great schema, for the tonsure was taken very seriously. Besides, the stravrophore tonsure itself was difficult to fulfill, as it should be in a monastery. The schema was not worn openly, but hidden under clothing.

In accordance with St. Seraphim’s commandment, all church obediences were carried by maidens (just as was the prosphora making obedience).

The church laundry was washed by the ecclesiarchs using special basins, and the wash water was poured into special wells set aside for that purpose.

The Monastery’s means were limited, as I have mentioned, and therefore the sisters were sent out into the world to collect donations. This was a very difficult obedience.

In every cell building there was an established order: the younger sisters took turns staying home, maintaining the fire in the stoves, cleaning the quarters, carrying water, taking the washwater and garbage outside the monastery, washing the dishes, and fetching bread and meals in the trapeza, for they ate in the trapeza itself only on feast days. They also fetched kvass, cucumbers, and cabbage, and ate in their own buildings.

On Sundays and feast days, during Passion Week and the first week of Great Lent, all of the younger sisters who were able went to church. On other days they went as they liked whenever they had time free from obediences. The services in the Monastery were beautiful. The singing was especially good. There were so many singers that you could not count them all. Those who had more musical talent were taught to play the violin and harmonium. Diveyevo was famous for its choir directors. There were many of them, for the monastery and its metochion required many singers. In the summer, when there were many pilgrims, Liturgy and Vigils were served in several churches at once, and Molebens and Pannikhidas were sung in the hermitages, so that the singers rarely had to work in the workshops.

The services were conducted according to the complete rule. During Great Lent and on Sundays they sang all the Old Testament prayers.

On the day of the Nativity of Christ the entire Monastery went to congratulate the Abbess, and to sing Christmas carols. They went separately by buildings, and it was very solemn and festive.

The quarters were all cleaned thoroughly before feasts. The unpainted floors were washed till they were white and then covered with new home-made floor-mats, and the beds were decorated with clean bed-spreads. There was no work for three days at Christmas and all of Bright Week—they only went to church, to the hermitages, walked along the Canal, and read spiritual books at home. The poor choral sisters often lost their voices by the end of Bright Week from the continuous singing of the services, for at Pascha all the services are replaced with singing, and instead of the monastic rule after Vespers the entire Paschal Canon was sung. When I joined the Monastery, I was most amazed at how they conducted Great Lent in the Monastery, and how joyfully they greeted the feasts.

The Monastery trapeza was very meager. On weekdays they served sour shchi (cabbage soup) with black mushrooms, kvass, cabbage, cucumbers and black bread. On feast days the sisters all went to the trapeza to eat. If there were three dishes they were kvass with fish, shchi and soup. If there were four dishes the fourth was kasha. In the obediences that brought income, they added some cooked food. This was accepted in such serious obediences as, for instance, painting. In the studio all the sisters’ energy went into their work, and if they did not receive extra rations, they would not be able to survive on the monastery fare [since they had no time to earn money]. Even so they all looked pale and fatigued, for they sat inside summer and winter without any fresh air, and worked so hard. The laborer-sisters always looked stronger and healthier from spending so much time in the fresh air doing physical work.

Work in the workshops began at 9:00 a.m. At 8:00 a.m. after Liturgy everyone had breakfast and drank tea. Potatoes were boiled. Dinner was from 11:00 to 12:00. At three was tea, at 5:00 the work day ended, and at 4:30 the rule was begun in the church. Supper was taken by some before, some after the Vigil. In the evening in the cell buildings the evening prayers were read by the sisters together. Those who did not go to church prayed at home—they read the Psalter, the rule, made prostrations, sang Akathists. The sisters walked along the Canal every evening. This was a combination of prayer and evening stroll. They went to bed at 10:00, for they had to rise early in the morning.

Stavrophore nuns were entrusted to a spiritual mother at the tonsure. In the latter times many sisters went to Schemanuns Anatolia and Seraphima[13] for spiritual guidance. The schemanuns taught them humility, patience, obedience and ceaseless Jesus prayer.

The young sisters stood in church in the middle rows, while the elderly and nuns stood by the benches or had their own little benches. They always stood in an orderly, reverential manner, without any conversation.

The Abbess’ place was by the right cliros, and at the beginning of Liturgy all the singers came out in pairs to bow to her, as did all the readers. After the Liturgy all came to receive her blessing. The Abbess made the sign of the cross over everyone. Prostrations were made in the church all together, according to the rubrics.

The monastery kept sisters’ booklets, where the names were written of all the sisters living and dead from the foundation of the monastery. Every sister tried to obtain such a commemoration booklet and to commemorate the reposed daily, especially on the days set aside for the commemoration of the dead. The reposed sisters were also commemorated at the proskimedia in the churches and at all the perpetual Psalter readings; thus in the Monastery no one was afraid to die—they would pray you out [of hell].

The reposed sisters were immediately washed, dressed and placed in the coffin. There were always coffins in storage. The reposed was taken right away into the church for the night, all during which the Psalter was read over her; on the next day after Liturgy they would perform the funeral rite and burial. All stavraphore and ryassaphore nuns were given a full monastic funeral.

The sisters most often died in the monastery hospital, where they were always tonsured into the mantle. The priests served them Communion every day, bringing the Holy Gifts after the early Liturgy.

They say that the tuberculosis patients died especially well. Many of them were vouchsafed visions before death. They would send a message to the Abbess to ask a blessing to die, and she would bless to die those who were thus fated. Not one service ever began without the Abbess’ blessing. The ecclesiarchs always asked a blessing to ring.

Sisters who were specially assigned, wearing special uniforms, washed the reposed. This was the rule: when a nun died, they rang the large bell twelve times, and when a ryassaphore nun died, they rang the small bell. At that moment everyone in the Monastery was to make twelve prostrations with the prayer, “Theotokos and Virgin Rejoice.” For several days following everyone prayed “Theotokos and Virgin Rejoice” twelve times after the Evening Prayers for the newly reposed.

This is how a sister would be moved from one building to another. The Steward or her assistant would come and take the icon of the one being transferred, who should then make a prostration to everyone and ask their forgiveness. Then she would be taken to another building, and there she should again make a prostration to everyone saying: “Do not abandon me, for the Lord’s sake.” After that she would bring her things to the new quarters. Sisters were transferred to new buildings for some kind of misdeed. Sisters went to visit their homeland only with the Abbess’ blessing, and for a period specifically indicated by her.

For overstaying their leave, sisters were also punished. For a great fault, they made full prostrations in trapeza at the common meal. At this time they would hand the guilty sister a prayer rope made of large, wooden beads, which would be heard throughout the entire trapeza as they knocked the ground with each prostration.

In general, sisters were not often transferred. Sometimes they would be given an obedience in their youth and stay there until they were old, having grown accustomed to their obedience and to the other sisters there.

The hardest thing of all was to be taken out of the cliros, or to be transferred from the right cliros to the left. This was the most woeful punishment, for it was hard to get used to a new environment.

All life, all interest, sorrows and joys were concentrated in the Monastery. It was as if no life existed outside the monastery. There were many nuns who had been brought, even carried, into the Monastery as little children, and they lived there until deep old age. My Matriusha was brought to the Monastery at the age of four, and she so loved it there that they had to force her to go to Vetrianovo for several hours to see her relatives. She immediately longed to go back to the Monastery. She was even afraid to go into the world, and always asked her brother to bring her home to the Monastery.

From Saint Seraphim, Wonderworker of Sarov and His

Spiritual Inheritance,

St. Xenia Skete,

Wildwood, CA, 2004

To be continued. See Part 2—"What I Heard from the Sisters, and What I Saw Myself"