(1751–1836)

The following Life is based on the original Valaam Life commissioned in 1864 by Abbot Damascene, and incorporates changes based on recent research.

Saint Herman of Alaska was born in 1751 in a village of the province of Voronezh, Russia, into a very devout peasant family. His name before monasticism was Yegor Ivanovich Popov. It is known that one of his relatives ended her days as a nun of the well-known Monastery of the Passion in Moscow. From his early youth Yegor was a pious boy, and he made several pilgrimages to the Sarov Monastery. During his childhood he stayed for a time in the cell of the elder and asceticVarlaam of Sarov (†1764), the spiritual father of Hieromonk Nazarius, the future abbot of Valaam Monastery. Little is known ofthe early period of Fr. Herman’s life. A story about him was told by his friend, monk Theophan.[1] “Fr. Herman (he is now in America) at a young age lived in the wilderness with Fr. Varlaam. Fr. Varlaam once departed for a short time, leaving the youngster—he was twelve years old—alone. It happened that some people gathering mushrooms in the forest became lost and came across the cell of the desert dwellers. When Yegor emerged to meet them, they were frightened by him—so unusual did his presence in the forest seem to them.”[2]

At the age of seventeen Yegor was conscripted into the military. At that time he again went to Sarov, and was taken from there into the army. Little is known about his military service, save that he served in the city of Kadom (near Ryazan) as an assistant clerk. The years he spent working on correspondence, occasioned by his work as a clerk, were subsequently reflected in the eloquence of his letters from Alaska, which displayed a talent quite rare among peasants.

During Yegor’s youth the following incident occurred. On the right side of his neck under his beard there appeared an abscess. The pain was horrible. The swelling grew rapidly and disfigured his whole face; it was very difficult to swallow and there was an intolerable smell. In such a dangerous condition, expecting to die, Yegor did not turn to an earthly physician, but, with warm prayer and tears he fell before the icon of the Heavenly Queen, entreating healing from her. He prayed the whole night, then with a wet towel he wiped the face of the icon of the Most Pure Theotokos, and with this towel he wrapped his swelling. Continuing to pray with tears he fell asleep on the floor in exhaustion and saw in a dream that he had been healed by the Most Holy Virgin. In the morning he awoke, stood up and, to his great amazement, found himself completely healthy; the swelling had dispersed without rupturing, leaving only a small lump as a reminder of the miracle. The doctors who were told about this healing did not believe it, insisting that the abscess must have burst by itself or must have been cut out. However, the words of the physicians were the words of the experience of human weakness; for where God’s grace acts, the order of nature is overcome. Such manifestations humble man’s mind under the mighty hand of God’s mercy!

In 1777, at the age of twenty-six, Yegor was released from the army due to illness, and the following year he was accepted as a novice in the Sarov Monastery. That same year Prokhor Moshnin, the future St. Seraphim of Sarov, also began his novitiate there. In 1781 Metropolitan Gabriel of Novgorod and St. Petersburg began to consider assigning Hieromonk Nazarius of Sarov[3] as superior of Valaam Monastery. The monastery, situated on an archipelago in the great Lake Ladoga, on the Russian-Finnish border, had long been in a state of decline. At that time there were only four inhabitants there: two former parish priests, one monk, and the superior, Abbot Ephraim. During the autumn of 1781 both priests and the monk drowned while crossing Lake Ladoga. Abbot Ephraim was relieved of his post in January 1782, and he reposed in March of the same year. By a Synodal decree issued on March 7, 1782, Fr. Nazarius was assigned as abbot of Valaam. Having been informed earlier of his selection as the new superior, he was at that time on a pilgrimage to the Valaam and Konevits monasteries with four Sarov novices, one of whom was Yegor Popov. Fr. Nazarius’ choice of novices to accompany him to his new position was not accidental. Of the four, three were former military men, and one had even been an officer. Such disciplined men were needed to lay the foundation of the new brotherhood.

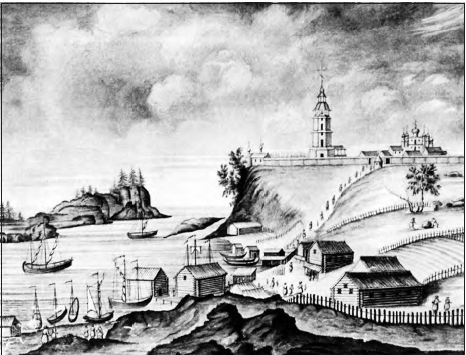

Valaam Monastery during the eighteenth century.

Valaam Monastery during the eighteenth century.

On November 1, 1782, two of the novices, Yegor Popov and Peter Matchin, were tonsured—Yegor receiving the name Herman, and Peter the name Patermuphius. Thus St. Herman was among the first monks tonsured in the newly revived Valaam monastery. Fr. Herman came to love Valaam and its brotherhood with his whole soul, and he remembered Elder Nazarius with gratitude to the end of his days. “Thy paternal kindness and deeds of love toward my lowliness,” he later wrote to Abbot Nazarius from America, “shall in no way ever be erased from my heart. Neither the terrible impassible Siberian wilds, nor its dark forests, neither the rapids of great rivers, nor the dread ocean can quench these feelings of mine. For in my mind I imagine my beloved Valaam and constantly behold it across the great ocean.”[4] In his letters he addressed Elder Nazarius as “my most venerable, beloved Batiushka,” and all of the Valaam brethren he called “beloved and most treasured.” He named the deserted Spruce Island, his place of habitation in America, “New Valaam.” And, as is apparent, he was always in contact with his spiritual homeland. As late as 1823, thirty years after his arrival in the American territory, he wrote letters to Fr. Nazarius’ successor, Abbot Innocent. Here is what is said concerning the life of Fr. Herman on Valaam by his contemporary, who was also tonsured by Abbot Nazarius and was a future abbot of Valaam—Fr. Varlaam: “Fr. Herman went through various obediences, and as being ready for any good thing, he was, among other things, sent to the city of Serdobol[5] in order to supervise the marble quarry there. The brethren loved Fr. Herman and would impatiently await his return from Serdobol to the monastery. Having tested the zeal of the ascetic, the wise elder, Fr. Nazarius, let hi was located in a dense forest, about a mile’s distance from the monastery. There is now a cultivated field on that site, which has retained the name ‘Germanova Polye’ [Herman’s Field]. On feast days Fr. Herman would come from his hermitage to the monastery. It would happen that during Compline, standing in the cliros, he would sing in a pleasant tenor voice the refrains of the canon: ‘Sweetest Jesus, save us sinners’ and ‘O Most Holy Theotokos, save us’—and tears like hail would pour from his eyes.”

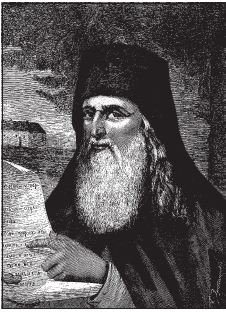

AbbotNazarius In the second half of the eighteenth century the boundaries of Holy Russia on the northeast were being enlarged through the activity of Russian promyshlenniki (trappers and pioneers). The Aleutian islands were discovered, which comprise a chain on the Pacific Ocean from the eastern border of Kamchatka to the western shore of North America. With the discovery of these islands the need was seen to enlighten the inhabitants with the Gospel of Christ. For this holy task, with the blessing of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Gabriel entrusted Elder Nazarius with selecting capable men from among the brethren of the Valaam and Konevits monasteries. Ten men were chosen,[6] and one of their number was Fr. Herman. In 1794 they set out from Valaam Monastery for their appointed destination, the island of Kodiak in the northern part of the Gulf of Alaska. This was at that time the headquarters of the Russian colonies in North America. With holy zeal the preachers quickly spread the light of the Gospel to the new sons of Russia. Several thousand people accepted Christianity. A school was founded to educate the newly baptized children. A wooden church, dedicated to Christ’s Resurrection, was built near Kodiak harbor, as was a wooden monastery for the members of the mission. But by the unfathomable ways of God the general success of the mission was not long lasting. Members of the Russian-American Trading Company, headed by Alexander Baranov, continually persecuted the monks for defending the local natives who were being exploited and virtually enslaved by the Company.

AbbotNazarius In the second half of the eighteenth century the boundaries of Holy Russia on the northeast were being enlarged through the activity of Russian promyshlenniki (trappers and pioneers). The Aleutian islands were discovered, which comprise a chain on the Pacific Ocean from the eastern border of Kamchatka to the western shore of North America. With the discovery of these islands the need was seen to enlighten the inhabitants with the Gospel of Christ. For this holy task, with the blessing of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Gabriel entrusted Elder Nazarius with selecting capable men from among the brethren of the Valaam and Konevits monasteries. Ten men were chosen,[6] and one of their number was Fr. Herman. In 1794 they set out from Valaam Monastery for their appointed destination, the island of Kodiak in the northern part of the Gulf of Alaska. This was at that time the headquarters of the Russian colonies in North America. With holy zeal the preachers quickly spread the light of the Gospel to the new sons of Russia. Several thousand people accepted Christianity. A school was founded to educate the newly baptized children. A wooden church, dedicated to Christ’s Resurrection, was built near Kodiak harbor, as was a wooden monastery for the members of the mission. But by the unfathomable ways of God the general success of the mission was not long lasting. Members of the Russian-American Trading Company, headed by Alexander Baranov, continually persecuted the monks for defending the local natives who were being exploited and virtually enslaved by the Company.

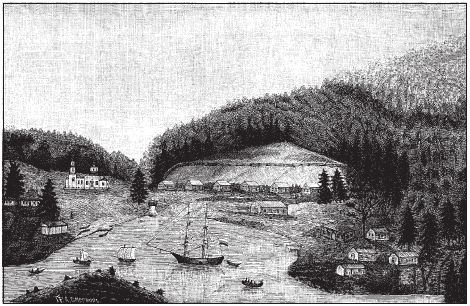

Kodiak harbor as it looked during St. Herman’s time. The Resurrection Church is at left.

Kodiak harbor as it looked during St. Herman’s time. The Resurrection Church is at left.

Also, after five years of greatly profitable activity, the head of the mission, Archimandrite Ioasaph, drowned along with his whole retinue, which included Hieromonk Macarius and Hierodeacon Stephen. He had been raised to the rank of bishop in Irkutsk, Russia, but suffered shipwreck on his return trip. Before him, the zealous Hieromonk Juvenal had been vouchsafed a martyric crown, while others one after another left the mission, leaving only Hieromonk Athanasius, Monk Ioasaph, and Monk Herman. Eventually, after the death of the first two, Fr. Herman was the only one left from the original group.

Fr. Herman moved to Spruce Island, which, as was noted above, he called “New Valaam.” This island is separated by a strait over a mile wide from Kodiak Island. Spruce Island is not large, and is covered with forest. Fr. Herman chose this picturesque island for himself as a place of seclusion, and dug a cave in the ground there with his own hands, spending his first whole summer in it. By winter the Russian-American Company built a cell for him near his earthen cave. He lived in this cell until his death, turning the cave into a grave for his repose. Not far from the cell was a wooden chapel dedicated to the Meeting of the Lord, as well as a small wooden house for his school (about which more will be said later) and for visitors. This was the whole arena of Fr. Herman’s great ascetic labors over the course of nearly forty years of his life. Here in the garden he himself dug the beds and planted potatoes, cabbage, and other vegetables. He stored mushrooms for winter, salting and drying them. He prepared salt from seawater. The basket in which the Elder carried kelp from the shore in order to fertilize the earth was so big, they say, that it was hard for one man to lift by himself. Fr. Herman, however, to the amazement of all, would carry it without any assistance for long distances. One winter night his disciple Gerasim happened to see him in the woods walking barefoot, bearing a log so large that it would have taken four men to carry it. His clothing was the same winter and summer. He did not wear a shirt. Instead he wore a deerskin garment, which for eight years he neither removed nor changed. Consequently, all the fur wore off and it became soiled. He also wore boots or shoes, a worn-out, faded robe covered with patches, a riassa,[7] and a klobuk.[8] He went everywhere in this clothing, in all types of weather: in rain, snow, winter storm, and in the most severe frosts.

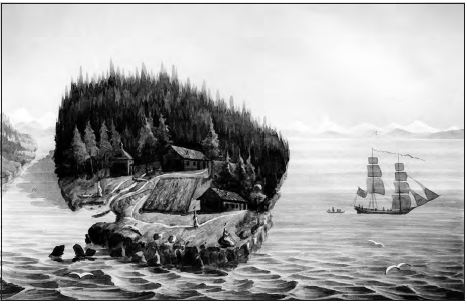

Spruce Island in St. Herman's time.

Spruce Island in St. Herman's time.

A medium-sized bench, covered with deerskins, the fur of which had worn out with time, served as his bed. For his pillow he had two bricks which were hidden under the deerskins and thus unseen by visitors. He had no blanket. This was replaced by a wooden board which lay on his stove. Fr. Herman called this board his blanket and willed to have his mortal remains covered with it. It was fully his size. “When I visited Fr. Herman’s cell,” stated Constantine Larionov, “I, the sinful one, sat on his bed, and I consider it the height of my happiness!”

Fr. Herman would occasionally be a guest amidst the Company’s managers in Kodiak. He would speak on soul-saving matters and would sit with them up to, and even past, midnight. He would not stay to spend the night with them, and no matter what kind of weather there was, he would always walk back to his cell at the mission. If for some special reason he was compelled to spend the night away from his cell, his hosts would always find that the bed that had been prepared for him had been untouched, and that the Elder had not slept at all. Exactly the same thing would happen in his desert hermitage. Having spent the night in conversation, he would not give himself over to rest.

The Elder ate very little. When visiting, he would barely taste some dish and would remain without dinner. In his cell, a very small portion of fish or vegetables constituted his whole meal.

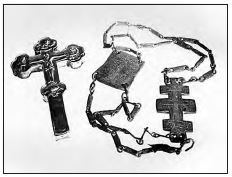

His body, worn out by labors, vigils, and fasting, was weighed down by fifteen-pound chains. These chains at the present time are treasured in the chapel where, it has been said by some, they were found behind an icon of the Mother of God at the Elder’s death; or they fell out from behind there at his death, as others explain.[9]

Aleuts. Describing these ascetic labors of Fr. Herman, his disciple, Aleut[10] Ignatius Aligyaga (†1874) added: “Yes, Apa[11] conducted a hard life, and no one can imitate it.” The above-described characteristics of the Elder refer, so to say, to his outward activity. “But his main activity,” as Bishop Peter of New Arkhangelsk (†1889) said, “was the exercise of spiritual labors in the seclusion of his cell, where no one saw him. Only from outside his cell was he heard singing and performing the services in accordance with the monastic rule.” The bishop’s testimony is confirmed by the following reply of Fr. Herman himself. The Elder was asked: “How do you, Fr. Herman, live alone in the forest? How do you keep from being bored?” He responded: “No! I’m not alone there! God is there, as God is everywhere! Holy angels are there! Can one be bored with them? With whom is it better and more pleasant to converse—with people or with angels? With angels, of course!”

Aleuts. Describing these ascetic labors of Fr. Herman, his disciple, Aleut[10] Ignatius Aligyaga (†1874) added: “Yes, Apa[11] conducted a hard life, and no one can imitate it.” The above-described characteristics of the Elder refer, so to say, to his outward activity. “But his main activity,” as Bishop Peter of New Arkhangelsk (†1889) said, “was the exercise of spiritual labors in the seclusion of his cell, where no one saw him. Only from outside his cell was he heard singing and performing the services in accordance with the monastic rule.” The bishop’s testimony is confirmed by the following reply of Fr. Herman himself. The Elder was asked: “How do you, Fr. Herman, live alone in the forest? How do you keep from being bored?” He responded: “No! I’m not alone there! God is there, as God is everywhere! Holy angels are there! Can one be bored with them? With whom is it better and more pleasant to converse—with people or with angels? With angels, of course!”

How Fr. Herman regarded the native inhabitants of America, how he understood his relationship to them and how he had compassion for their needs, he himself expressed in one letter addressed to the former governor of the colonies, Symeon Ivanovich Yanovsky: “The Creator has given to our beloved fatherland this region like a new-born babe, still without strength or knowledge of any kind, nor sense, which demands not only protection, but also, because of its weak and tender age, support. But it is still not even possible to ask anyone to do this. The dependence of this people is a blessing of Holy Providence, given as it is into the hands, for an unknown period of time, of the Russian authorities here, and now given into your hands. For this reason I, the most humble servant of the local peoples and their nurse, stand before you with bloody tears and write my request: be a father and protector to us! We, of course, know not eloquence, but we say, with the halting tongue of children, wipe away the tears of defenseless orphans, cool the heat of sorrow in melting hearts, give us to know the meaning of consolation.”[12]

As the Elder felt, so also did he act. He always interceded before the authorities on behalf of transgressors, defended those who were being hurt, and helped the needy in any way he could. Aleuts of both sexes, as well as their children, would often visit him. Some would ask for advice, others would complain of oppression, yet others sought defense, or requested help. Everyone would receive satisfaction from the Elder as far as this was possible. He looked into troubles that arose between them and tried to reconcile everyone. He especially strove to restore harmony in families. If he did not succeed in reconciling a husband and wife, the Elder would separate them for a while. The necessity of such measures he explained thus: “It is better to let them live separately, so that they do not fight and quarrel; otherwise, believe me, it is frightful if you don’t take them apart: there were cases where the husband would kill his wife or the wife would drive her husband to madness!”

Fr. Herman especially loved children. He would give them crackers, and bake pretzels for them; and the little ones were especially attracted to his gentleness. Fr. Herman’s love for the Aleuts reached self-denial.

St. Herman's chains. In late 1819 an infectious, deadly disease was brought by way of a ship from the United States to the island of Sitka and from there to the island of Kodiak. As the colonial governor at the time, S. I. Yanovsky, related, “It began with a fever, intense runny nose and shortness of breath, and would end in spasms: in three days the victim would die. On the island there was neither doctor nor medication. The disease, spreading through villages, would quickly embrace the whole vicinity…. The epidemic affected all, even suckling babes. The death toll was so great that for three days there was no one to dig graves and the bodies lay all over unburied! … I cannot imagine anything more sorrowful, more horrible than that sight with which I was struck when I visited an Aleut dwelling! This was a large barn, or a barrack with bunk beds, where whole Aleut families lived and which could lodge as many as a hundred people…. Some were dying, their bodies growing cold, stretched out next to the living; others were already dead; there was moaning and wailing that tore one’s soul apart! I saw mothers already dead, upon whose cold breasts crawled hungry little infants, futilely and with cries seeking food for themselves. My heart bled from pity! One would think that if one could, with a worthy brush, depict all the horror of this sorrowful picture, that it would evoke the fear of death even in hardened souls.”[13] During the whole time the terrible disease lasted—an entire month with a gradual decline—Fr. Herman, not sparing himself, tirelessly visited the sick, begged them to be patient, to pray, and to bring forth repentance, and he would prepare them for death.

St. Herman's chains. In late 1819 an infectious, deadly disease was brought by way of a ship from the United States to the island of Sitka and from there to the island of Kodiak. As the colonial governor at the time, S. I. Yanovsky, related, “It began with a fever, intense runny nose and shortness of breath, and would end in spasms: in three days the victim would die. On the island there was neither doctor nor medication. The disease, spreading through villages, would quickly embrace the whole vicinity…. The epidemic affected all, even suckling babes. The death toll was so great that for three days there was no one to dig graves and the bodies lay all over unburied! … I cannot imagine anything more sorrowful, more horrible than that sight with which I was struck when I visited an Aleut dwelling! This was a large barn, or a barrack with bunk beds, where whole Aleut families lived and which could lodge as many as a hundred people…. Some were dying, their bodies growing cold, stretched out next to the living; others were already dead; there was moaning and wailing that tore one’s soul apart! I saw mothers already dead, upon whose cold breasts crawled hungry little infants, futilely and with cries seeking food for themselves. My heart bled from pity! One would think that if one could, with a worthy brush, depict all the horror of this sorrowful picture, that it would evoke the fear of death even in hardened souls.”[13] During the whole time the terrible disease lasted—an entire month with a gradual decline—Fr. Herman, not sparing himself, tirelessly visited the sick, begged them to be patient, to pray, and to bring forth repentance, and he would prepare them for death.

The Elder took special care for the moral improvement of the Aleuts. With this aim he created a school not far from his cell for the orphaned Aleut children. All that he was able to acquire through his toil in his garden he utilized to provide food, clothing, and books for his orphans. He himself taught them the Law of God and church singing. With this in mind he would gather the Aleuts for prayer in the chapel near his cell on Sundays and feast days. His disciple would read the Hours and other prayers for them there. The Elder himself would read the Apostolic Epistles and Gospels and teach them. His female students would sing, and they sang very nicely. The Aleuts loved to listen to Fr. Herman’s instructions, and would gather with him in large numbers. The Elder’s talks were very interesting, and influenced his listeners with a wonderful power. He personally wrote about one such grace-filled impression produced by his word: “Glory to the holy ways of the merciful God! By His unfathomable Providence He has shown me a new phenomenon which I have not yet seen in the twenty years I have lived in Kodiak. Just after Pascha one young woman, not more than twenty years old, who knows how to speak Russian well and who had previously neither known nor seen me, came to me. After hearing about the Incarnation of the Son of God and about eternal life, she became so inflamed with love for Jesus Christ that she does not want to leave me at all. But her intense entreaty convinced me, against my inclination and love of seclusion, to accept her. Despite all the hindrances and difficulties that I presented to her, she has been living with me for over a month and is not bored. Looking upon this with great amazement, I recall the words of the Savior: Thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent and hast revealed them unto babes (Matt. 11:25).” This woman lived near the Elder until his death; she watched over the good behavior of the children who studied in his school. When he was dying, he willed her to live on Spruce Island and to be buried at his feet upon her death. Her name was Sophia Vlasova.[14]

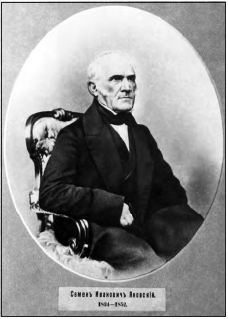

Symeon Ivanovich Yanovsky (†1876), governor of the Alaskan colonies. Concerning the character and power of the Elder’s talks, Yanovsky writes: “I was thirty years old when I met Fr. Herman. It must be said that I was educated in a naval academy, knew many sciences, and had read much. But, unfortunately, the science of sciences, i.e., the Law of God, I understood superficially, and even that theoretically, not applying it to life, and was a Christian in name only, while in my soul and my actions I was a free thinker, a deist. Moreover I did not accept the divinity and holiness of our religion, and I had read many atheistic works of Voltaire and other philosophers of the eighteenth century. Fr. Herman noticed this at once and desired to convert me. To my great amazement he spoke so powerfully and intelligently, and argued so convincingly, that it now seems to me that no education and earthly wisdom could withstand his words.We conversed with him every day until, and sometimes later than, midnight about the love of God, about eternity, about the salvation of the soul, and about Christian life. Sweet speech poured from his lips in an unceasing stream! Through such continual conversations and by the prayers of the holy Elder, the Lord completely converted me to the path of truth, and I became a true Christian. For all this I am indebted to Fr. Herman: he is my true benefactor.”

Symeon Ivanovich Yanovsky (†1876), governor of the Alaskan colonies. Concerning the character and power of the Elder’s talks, Yanovsky writes: “I was thirty years old when I met Fr. Herman. It must be said that I was educated in a naval academy, knew many sciences, and had read much. But, unfortunately, the science of sciences, i.e., the Law of God, I understood superficially, and even that theoretically, not applying it to life, and was a Christian in name only, while in my soul and my actions I was a free thinker, a deist. Moreover I did not accept the divinity and holiness of our religion, and I had read many atheistic works of Voltaire and other philosophers of the eighteenth century. Fr. Herman noticed this at once and desired to convert me. To my great amazement he spoke so powerfully and intelligently, and argued so convincingly, that it now seems to me that no education and earthly wisdom could withstand his words.We conversed with him every day until, and sometimes later than, midnight about the love of God, about eternity, about the salvation of the soul, and about Christian life. Sweet speech poured from his lips in an unceasing stream! Through such continual conversations and by the prayers of the holy Elder, the Lord completely converted me to the path of truth, and I became a true Christian. For all this I am indebted to Fr. Herman: he is my true benefactor.”

“Several years ago,” continues Yanovsky, “Fr. Herman converted one naval captain, Leonty [Ludwig] Adrianovich Hagemeister, from the Lutheran faith to Orthodoxy. This captain was quite educated. Besides many sciences he knew many languages: Russian, German, French, English, Italian, and a bit of Spanish. In spite of all this he could not resist the arguments and proofs of Fr. Herman: he changed his beliefs and was received into the Orthodox Church through Chrismation. When he was leaving America, the Elder said to him at parting: ‘See to it that if the Lord takes your wife, you will by no means marry a German woman; if you marry a German woman she will unfailingly hurt your Orthodoxy.’ The captain gave his word, but did not keep it. The Elder’s warning was prophetic. Several years later the captain’s wife did die, and he married a German [in 1827]. He evidently either abandoned or weakened his faith, and died suddenly, without repentance.”

Yanovsky continues: “Once the Elder was invited to a frigate that had arrived from St. Petersburg. The captain of the frigate[15] was a rather learned man, highly educated. He had been sent to America by imperial decree to inspect all the colonies. There were at least twenty-five officers with the captain, likewise educated men. In this company sat a man of rather short stature, with worn-out clothing— a desert-dwelling monk, who with his wise conversation brought all these educated men to such a state that they did not know how to answer him. The captain himself related: ‘We were at a loss how to answer, like fools before him!’ Fr. Herman posed one common question to all of them: ‘What do you, gentlemen, love more than anything else, and what would each of you wish for your happiness?’ Various responses began to pour out. Some wished for riches, others glory, others a beautiful wife, others a beautiful ship that he would command, and so on in the same vein. ‘Isn’t it true,’ said Fr. Herman to them, ‘that all your various wishes could be summed up in one—that each of you wishes that which, according to his understanding, he considers the best and most worthy of love?’ ‘Yes, that is true!’ they all replied. ‘Tell me,’ he continued, ‘what could be better, higher than all, more superlative and most worthy of love if not the Lord, our Jesus Christ Himself, Who created us, adorned us with such good qualities, gave life to all, maintains and nourishes everything, loves everyone, Who is Himself love, and is more wonderful than all people? Shouldn’t one therefore love God far more than all things, and desire and seek Him more than anything?’ All began to speak: ‘Well, yes! That is self-evident! That is true in itself!’ ‘But do you love God?’ the Elder then asked. All replied: ‘Of course we love God. How can one not love God?’ ‘And I, a sinner, have been trying to love God for more than forty years, and cannot say that I perfectly love Him,’ replied Fr. Herman, and he began to demonstrate how one must love God. ‘If we love someone,’ he said, ‘we always remember him and try to please him; day and night our heart is occupied with that object. Is that how you, gentle-men, love God? Do you often turn to Him, do you always remember Him, do you always pray to Him and fulfill His holy commandments?’ They had to admit that they did not. ‘For our good, for our happiness,’ concluded the Elder, ‘at least let us make a vow that from this day, from this hour, from this minute we shall strive to love God above all else and to fulfill His holy will!’ What a wise and wonderful talk Fr. Herman conducted in society: without a doubt this conversation must have been impressed in the hearts of his listeners for the rest of their lives!”

In general Fr. Herman liked to talk. He spoke wisely, to the point, and instructively, mostly on the points of eternity, salvation, the future life, and the ways of God. He would recount much from the Lives of the Saints and from the Prologue, but he never said anything frivolous. It was so pleasant to listen to him that those who conversed with him, even Aleuts and their women, were delighted with his talks and frequently only at dawn would they leave him, unwillingly as it were, as Constantine Larionov testified.

Yanovsky describes Fr. Herman’s outward appearance in detail. “I clearly remember,” he says, “all the features of the Elder’s face, which shone with grace: his pleasant smile, meek and attractive gaze, his humble, quiet manner, and his amiable words. He was not tall, he had a pale face, covered with wrinkles, his eyes were gray-blue and full of brightness, and on his head he had a few gray hairs. His speech was not loud, but very pleasant.” From his talks with the Elder, Yanovsky recalls two incidents. “Once,” he writes, “I read Derzhavin’s ode ‘God’ to Fr. Herman. The Elder was amazed and ecstatic, and asked that I read it once more, which I did. ‘Is it possible that this was written by an ordinary scholar?’ he asked. ‘Yes, he was a scholar, a poet,’ I answered. ‘It was written by the inspiration of God,’ said the Elder.

St. Peter the Aleut. Another time I was telling him how the Spaniards in California had captured fourteen Aleuts in 1815, and the Jesuits[16] were pressuring them all to accept the [Roman] Catholic faith, which the Aleuts in no way agreed to. ‘We are Christians,’ they said. ‘Not true, you are heretics and schismatics,’ argued the Jesuits, ‘and if you do not agree to accept our faith, we will torture all of you.’ Then the Aleuts were placed in prison cells by twos. In the evening the Jesuits came to the prison with lamps and lit candles and again began to try to persuade two Aleuts there to accept the [Roman] Catholic faith. ‘We are Christians,’ was the answer of the Aleuts, ‘and will not change our faith!’ Then the Jesuits had them tortured—at first one, while the other was a witness. They cut off one joint on the Aleut’s toe, and then the second joint, then one joint of his finger and then a second. Then they chopped off his feet and hands; the blood flowed. The martyr endured and firmly repeated the same thing: ‘I am a Christian.’ In such torments he died from loss of blood. The Jesuits promised to torture his friend the same way on the next day, but that night they received an order from Monterey that all captive Russian Aleuts should immediately be delivered there by convoy. Therefore, in the morning all of them, except the deceased Aleut, were sent away. This was told to me by the Aleut witness, the companion of the one who had been tortured, who had later escaped from captivity. I then reported this to headquarters in St. Petersburg. When I had finished my story, Fr. Herman asked: ‘And what was the name of the tortured Aleut?’ ‘Peter,’ I responded, ‘but I don’t remember his last name.’ Then the Elder stood up before the icon, reverently crossed himself and said: ‘Holy new martyr Peter, pray to God for us!’”

St. Peter the Aleut. Another time I was telling him how the Spaniards in California had captured fourteen Aleuts in 1815, and the Jesuits[16] were pressuring them all to accept the [Roman] Catholic faith, which the Aleuts in no way agreed to. ‘We are Christians,’ they said. ‘Not true, you are heretics and schismatics,’ argued the Jesuits, ‘and if you do not agree to accept our faith, we will torture all of you.’ Then the Aleuts were placed in prison cells by twos. In the evening the Jesuits came to the prison with lamps and lit candles and again began to try to persuade two Aleuts there to accept the [Roman] Catholic faith. ‘We are Christians,’ was the answer of the Aleuts, ‘and will not change our faith!’ Then the Jesuits had them tortured—at first one, while the other was a witness. They cut off one joint on the Aleut’s toe, and then the second joint, then one joint of his finger and then a second. Then they chopped off his feet and hands; the blood flowed. The martyr endured and firmly repeated the same thing: ‘I am a Christian.’ In such torments he died from loss of blood. The Jesuits promised to torture his friend the same way on the next day, but that night they received an order from Monterey that all captive Russian Aleuts should immediately be delivered there by convoy. Therefore, in the morning all of them, except the deceased Aleut, were sent away. This was told to me by the Aleut witness, the companion of the one who had been tortured, who had later escaped from captivity. I then reported this to headquarters in St. Petersburg. When I had finished my story, Fr. Herman asked: ‘And what was the name of the tortured Aleut?’ ‘Peter,’ I responded, ‘but I don’t remember his last name.’ Then the Elder stood up before the icon, reverently crossed himself and said: ‘Holy new martyr Peter, pray to God for us!’”

In order to express somewhat the spirit of Fr. Herman’s teachings, we shall cite here the words of one of his own letters:

“A true Christian is made so by faith and love toward Christ. Our sins do not in the least hinder our Christianity, according to the words of the Savior Himself. He deigned to say: ‘I came not to call the righteous, but sinners to salvation’ (cf. Luke 5:32); ‘There is more joy in heaven over one who repents than over ninety righteous ones’ (cf. Luke 15:7). Likewise concerning the sinful woman who touched his feet, He deigned to say to Simon the Pharisee: ‘To one who has love, a great debt is forgiven, but from one who has no love, even a small debt will be required’ (cf. Luke 7:47). From these considerations a Christian should bring himself to hope and joy, and pay not the least attention to despair that is inflicted on one. Here one needs the shield of faith.

“Sin, to one who loves God, is nothing other than an arrow from the enemy in battle. A true Christian is a warrior fighting his way through the regiments of the unseen enemy to his heavenly homeland, according to the words of the Apostle: ‘Our homeland is in heaven’ (cf. Phil. 3:20). About warriors he says: ‘Our warfare is not against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers’ (cf. Eph. 6:12).

“The vain desires of this world separate us from our homeland; love for them and habit clothe our soul, as it were, in a hideous garment. This is called by the Apostles the outward man.We, traveling on the journey of this life and calling upon God to help us, must divest ourselves of this hideousness and clothe ourselves in new desires, in a new love of the age to come, and thereby receive knowledge of how near or how far we are from our heavenly homeland. But it is not possible to do this quickly; rather one must follow the example of sick people who, wishing the desired health, do not leave off seeking means to cure themselves.”[17]

Pilgrims at St. Herman's miraculous spring. He never sought anything for himself in life. From the very time of his arrival in America, having out of humility refused ordination to the priesthood or the rank of archimandrite in order to remain always a simple monk, Fr. Herman, without the slightest fear of those in power, worked for God with all his zeal. With meek love, disregarding respect of persons, he reproached many for their unsober life, disrespectful behavior, and oppression of the Aleuts. The unmasked malice of these people rose against him, made every kind of trouble for him, and slandered him. The slanders were so powerful that often people of good will were unable to recognize the lies that appeared under the guise of outward truth in the accusations. Therefore one must say that it was the Lord alone that preserved the Elder. Before actually meeting Fr. Herman and instigated by slanders alone, S. I. Yanovsky wrote to St. Petersburg about the need to remove Fr. Herman, explaining that he was supposedly agitating the Aleuts against the authorities. A priest who came from Irkutsk with great authority gave Fr. Herman much sorrow and wanted to send him away to Irkutsk, but the colonial governor, Matthew Ivanovich Muraviev,[18] defended the Elder. Another priest, M., came to Spruce Island with the colonial governor N., together with company employees to search Fr. Herman’s cell, assuming that they would find great possessions there. When they did not find anything of value, the employee Ponomarkov, evidently with the permission of his superiors, began to pull out the floorboards with an axe. “My friend,” Fr. Herman then said to him, “in vain have you taken up this axe: such a tool will deprive you of your life!” After a certain period of time men were needed at the Nikolaev redoubt[19] on the Kenai Peninsula. Several Russian employees were therefore sent there from Kodiak, among whom was Ponomarkov. There, the Kenai natives severed his head with an axe while he was asleep.

Pilgrims at St. Herman's miraculous spring. He never sought anything for himself in life. From the very time of his arrival in America, having out of humility refused ordination to the priesthood or the rank of archimandrite in order to remain always a simple monk, Fr. Herman, without the slightest fear of those in power, worked for God with all his zeal. With meek love, disregarding respect of persons, he reproached many for their unsober life, disrespectful behavior, and oppression of the Aleuts. The unmasked malice of these people rose against him, made every kind of trouble for him, and slandered him. The slanders were so powerful that often people of good will were unable to recognize the lies that appeared under the guise of outward truth in the accusations. Therefore one must say that it was the Lord alone that preserved the Elder. Before actually meeting Fr. Herman and instigated by slanders alone, S. I. Yanovsky wrote to St. Petersburg about the need to remove Fr. Herman, explaining that he was supposedly agitating the Aleuts against the authorities. A priest who came from Irkutsk with great authority gave Fr. Herman much sorrow and wanted to send him away to Irkutsk, but the colonial governor, Matthew Ivanovich Muraviev,[18] defended the Elder. Another priest, M., came to Spruce Island with the colonial governor N., together with company employees to search Fr. Herman’s cell, assuming that they would find great possessions there. When they did not find anything of value, the employee Ponomarkov, evidently with the permission of his superiors, began to pull out the floorboards with an axe. “My friend,” Fr. Herman then said to him, “in vain have you taken up this axe: such a tool will deprive you of your life!” After a certain period of time men were needed at the Nikolaev redoubt[19] on the Kenai Peninsula. Several Russian employees were therefore sent there from Kodiak, among whom was Ponomarkov. There, the Kenai natives severed his head with an axe while he was asleep.

Fr. Herman also endured great sorrows from demons. This he revealed to his disciple Gerasim when the latter, entering the cell without the usual prayer, did not receive answers to any of his questions. The next day he asked for the cause of the previous day’s silence. “When I came to this island and settled in this wilderness,” Fr. Herman then said to him, “many times demons came to me as if from some need, both in human form and in the form of animals. I endured a lot from them: all kinds of sorrows and temptations; therefore, I now do not speak to anyone who comes into my cell without prayer.”

Having dedicated himself entirely to serving the Lord, laboring zealously in glorifying His All-Holy Name, being far from his homeland amidst diverse sorrows and deprivations, and spending many decades in labors of lofty self-denial, Fr. Herman was made worthy of many supernatural gifts from God.

In the middle of Spruce Island a little stream runs from the mountain into the sea, the mouth of which is continually washed by breakers. In the springtime, when the river fish would appear, the Elder would dig in the sand at the mouth of the stream so that the fish could just barely pass by, and would thus trap them. He kept little for himself, and would cut the rest into strips with which to feed birds, which would nest near his cell in great numbers. Under his cell there lived ermines. These little animals, after giving birth to their litters, are unapproachable, yet the Elder would feed them with his own hands. “Wasn’t that really a miracle we have seen!” said his disciple Ignatius. Fr. Herman was also seen feeding bears. “With the death of the Elder both the birds and the beasts went away; if someone tried to maintain the garden out of his own will it did not even give forth a crop,” asserted Ignatius.

Once there was a tidal wave (tsunami) on Spruce Island. The inhabitants ran in fear to the Elder. He then took an icon of the Mother of God from the house where the students lived, carried it out and placed it on the silty shore, and began to pray. After his prayer, he turned to those who were there and said: “Don’t be afraid—the water will not go further than the spot where the icon is standing!” The Elder’s word came true. Then, promising the same help from the icon in the future through the intercessions of the All-blameless Lady, he entrusted it to his disciple Sophia, so that in case of flood she would place it on the shore. The icon is preserved on the island.[20]

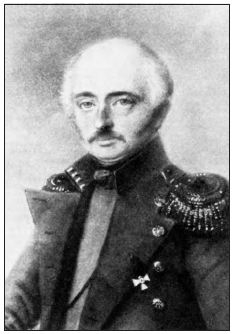

Baron Ferdinand P. Wrangell (†1870). Once, at the request of the Elder, Baron F. P. Wrangell wrote a letter dictated by Fr. Herman to a metropolitan—it is not known which one. When the letter was finished and read back to him, the Elder congratulated the baron with the rank of admiral. The baron was amazed. This was news to him, which was actually confirmed only after a long period of time, upon his departure to Petersburg.

Baron Ferdinand P. Wrangell (†1870). Once, at the request of the Elder, Baron F. P. Wrangell wrote a letter dictated by Fr. Herman to a metropolitan—it is not known which one. When the letter was finished and read back to him, the Elder congratulated the baron with the rank of admiral. The baron was amazed. This was news to him, which was actually confirmed only after a long period of time, upon his departure to Petersburg.

“I feel sorry for you, my dear kum,”[21] Fr. Herman once said to the administrator Kashevarov, whose son was his godson. “I feel sorry for you; the next change will be unpleasant for you!” About two years later, when the next change of personnel took place, he was sent to the island of Sitka in bonds.

Once the forest on Spruce Island caught fire. The Elder, together with his disciple Ignatius, made a clearing in the forest thickets about two feet wide to the foot of the hill, overturning the moss, and said: “Be at peace—the fire will not cross this line!” The next day when, according to Ignatius’ testimony, there was no hope for salvation, the fire with great force came up to the moss overturned by the Elder, ran along it, and stopped, not touching the dense forest on the other side of the line.

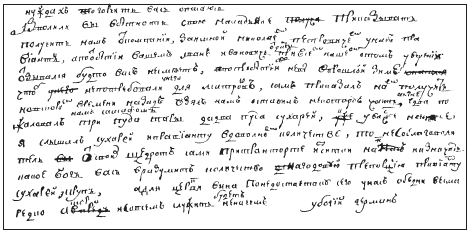

A letter written by St. Herman, in his own handwriting.

A letter written by St. Herman, in his own handwriting.

A year prior to the reception in Kodiak of news of the death of a metropolitan (it is not known which one), Fr.Herman told the Aleuts that their great spiritual leader had died.

Bishop Peter reported that the Elder often used to say that America would have its own bishop, and this was at a time when no one was thinking of this, nor was there any hope that there would be a bishop in America. But his prophecy came true in time.

“After my death,” Fr. Herman used to say, “there will be a plague and many people will die from it, and the Russians will bring the Aleuts together.” And truly, evidently half a year after his death a smallpox epidemic occurred; its fatality in America was staggering: in several villages only a few people remained alive. This compelled the colonial authorities to unite the Aleuts: those who remained out of twenty villages were brought together into seven.

“Although much time will pass after my death,” Fr. Herman used to say to his disciples, “I will not be forgotten, and the place where I lived will not be empty: a monk similar to me, fleeing the glory of men, will come and will live on Spruce Island. And Spruce Island will not be without people!”

“My dear one,” Fr. Herman once asked Constantine, when he was no more than twelve years old, “what do you think? Will the chapel which they are now building be abandoned?” “I don’t know, Apa,” answered the little one. “And really,” said Constantine in later years, “I didn’t understand the question then, although this whole conversation with the Elder was vividly impressed on my memory.” The Elder, after being silent for a while, said, “My child, remember that on this spot there will be a monastery in time.”

Fr. Herman used to say to his disciple Ignatius Aligyaga, “Thirty years will pass after my death, and all those who live now on Spruce Island will be dead. You alone will remain alive, and you’ll be old and poor, and then they will remember me.” “It’s remarkable,” exclaimed Ignatius, “how a man like us could know all this in advance, and such a long time in advance! But no! He was not a simple man! He saw our thoughts and would involuntarily lead us to reveal them to him, and we would receive instruction.”

“When I die,” the Elder would tell his disciples, “bury me next to Fr. Ioasaph. Kill my bullock at once: he has served me enough. Bury me by yourselves and don’t inform those at the harbor of my death. Those who live at the harbor [Kodiak] will not see my face. Don’t send for a priest and don’t wait for him: your waiting will be in vain! Do not wash my body; place it on the board, fold my arms on my chest, wrap me in my mantle and with its edges cover my face, and cover my head with my klobuk. If someone wishes to say farewell to me, let him kiss the cross [in my hands]; do not show anyone my face.[22] After lowering me into the earth cover me with my blanket.” This blanket, as we have mentioned above, was the board that was always in his cell.

The time was approaching for the Elder’s departure. One day he directed his disciple Gerasim to light candles before the icons and read the Acts of the Apostles. After some time the Elder’s face shone and he said loudly: “Glory to Thee, O Lord!” Then, ordering him to stop the reading, he said that it was pleasing to the Lord to prolong his life for one more week. A week later, again according to his order, the candles were lit and the Acts of the Apostles was read. The Elder quietly leaned his head on Gerasim’s chest; the cell was filled with fragrance and his face was shining—and Fr. Herman was no more! Thus he blessedly reposed in the sleep of the righteous on December 13, 1836.[23]

Despite Fr. Herman’s will, expressed before his repose, his disciples could not bring themselves to bury him without letting anyone in the harbor knowabout his death. They were afraid of the Russians, the Aleuts said. Also, for some unknown reason they did not kill the bullock.

The reliquary of St. Herman of Alaska, located in the Church of the Holy Resurrection in Kodiak, Alaska.

The reliquary of St. Herman of Alaska, located in the Church of the Holy Resurrection in Kodiak, Alaska.

An envoy was sent with the sad news to the harbor, and on his return he informed them that Kashevarov, the manager of colonies, had forbidden them to bury the Elder until his arrival. He had ordered a better coffin to be made for the deceased and said that he himself and a priest would bring it without delay. However, such instructions were contrary to the will of the deceased. And so, a frightful wind blew, rain began to pour, and a terrible storm developed. The traveling distance from the harbor to Spruce Island was not a long one—only two hours—but no one would venture to put out to sea in such weather. It continued in such a way for a whole month. And although Fr. Herman’s body lay in the warm house of his students for the whole month, his face did not change, and there was not the slightest odor from his body. The coffin was finally delivered with the help of an experienced old man, Cosmas Uchilishchev. No one from the harbor came, and the inhabitants of Spruce Island gave the earthly remains of their Elder over to the earth themselves. Thus was Fr. Herman’s last wish fulfilled—and then the wind calmed down and the surface of the sea became as smooth as a mirror.

The day after Fr. Herman’s death, his bull began to miss him and out of despair struck his forehead against a tree and fell to the ground dead.[24]

One evening in the village of Katani (on Afognak Island) an extraordinary pillar of light that reached to heaven was seen over Spruce Island. Stunned by this miraculous phenomenon, some of the old people, as well as Creole[25] Gerasim Vologdin and his wife Anna, said to themselves: “It looks like Fr. Herman has left us!” and they began to pray. They were subsequently informed that the Elder had passed away on precisely that night. This pillar was seen in other places by others as well. On that same evening, in another village on Afognak Island, people saw a man being lifted up from Spruce Island to the clouds.

Having buried their father, his disciples erected a wooden memorial over his grave. “I saw it myself,” said Kodiak priest Peter Kashevarov, thirty years after the saint’s repose, “and I can say now that it has not been touched by time at all, and looks as if it had been put together today.”

Having seen Fr. Herman’s glorious life of ascetic labors, having seen his miracles, the fulfillment of his prophecies, and, finally, his blessed falling asleep, “in general all the local inhabitants have a reverent respect for him as a holy ascetic, and are entirely convinced of his having pleased God,” testified Bishop Peter.

In 1842, five years after the Elder’s repose, His Eminence Innocent, Archbishop of Kamchatka and the Aleutian Islands,[26] while sailing to Kodiak and finding himself in extreme danger, looked at Spruce Island and said mentally: “If thou, O Father Herman, hast pleased the Lord, then let the wind change!” And indeed, not even a quarter of an hour had passed, related the Archbishop, when the wind became favorable to them and they safely landed at the shore. Out of gratitude for his deliverance, Archbishop Innocent himself served a Pannikhida at the blessed one’s grave.

—Valaam Monastery

(written at the request of Abbot Damascene)

A Word on Source Materials

The Life of St.Herman presented here has been taken primarily from the original Life published by Valaam Monastery in 1868. This biography was based on information received by the monastery during the 1860s.

Upon the arrival of the missionaries in Kodiak, they began sending letters back to Valaam, informing the monastery of their activities.[27] Although these informational letters most likely continued to be sent throughout the stay of the Valaam monks in America, they were not all preserved in the monastery archives. Thus, in later years the labors and fate of the missionaries were known only through the writings of Alexander Skarlatovich Sturdza[28] and some others.[29] These writings described the general progress of the missionaries in the Russian-American territory, especially major events in the lives of these preachers, but lacked information about Monk Herman. In 1864 a pilgrim—who had lived in America for ten years and had known Fr. Herman’s closest disciple, Creole Gerasim Ivanov-Zyrianov (†1869)—brought this information to Valaam. The latter’s account was given in written form to the superior of Valaam Monastery, Abbot Damascene.

Abbot Damascene, desiring to learn about the former Valaam monk in more detail, sent out letters of inquiry in 1864 to Hierarch Innocent, Archbishop of Kamchatka and the Aleutians, to Bishop Peter, who had previously resided in New Archangelsk (Sitka) and was a vicar of the Kamchatka diocese, and to Gerasim Zyrianov. While awaiting this information, in 1865 Abbot Damascene received a letter from Symeon Ivanovich Yanovsky, who from 1817 to 1821 had been the governor of all the Russian-American colonies. Yanovsky had himself met St. Herman in 1819, had been converted by him from free-thinking, and had subsequently become his disciple. After his return to Russia, Yanovsky became a disciple of Elder Anthony (Putilov) of Optina Monastery, and ended his days in the St. Tikhon of Kaluga Monastery as Schemamonk Sergius. His letter to Abbot Damascene contained much information about St. Herman and was used as one of the primary sources for the biography published by Valaam.

In 1867 Abbot Damascene received letters in answer to his earlier inquiries. Bishop Innocent confirmed the truth of his miraculous deliverance from drowning through the intercession of Fr. Herman.[30] Bishop Peter submitted information about the Elder which was collected and written by Constantine Larionov, a citizen of Kodiak, a man worthy of credence. “I do not know,” wrote the bishop to the abbot, “whether Gerasim Zyrianov will send you any information about Fr. Herman, but I have, on my part, commissioned a Kodiak priest and a Kodiak citizen, Constantine Larionov, to write about all that they know or have heard from others about Fr. Herman. I have collected what I could and am hereby sending it to you.”[31]

However, it has become evident in recent years that some of the biographical information supplied by Yanovsky was erroneous, specifically the information concerning the saint’s early life. He had confused the biography of St. Herman with that ofMonk Ioasaph, one of the original members of the Ecclesiastical Mission, who lived with St. Herman in Kodiak and was eventually buried beside him on Spruce Island. Thanks to recent research by Dr. Lydia Sergeyevna Black and S. A. Korsun, more precise information on the identity and early years of St. Herman has become available,[32] based in part on the recollections of Baron Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangell, who was himself governor of Russian America after Yanovsky.We have corrected any erroneous information, but have otherwise left the Prima Vita of the Saint as it appeared in the original Valaam publication.

By the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood. Reprinted with permission.

The 1894 Russian-language publication about the life of St. Herman of Alaska (originally published by Valaam Monastery) can be found in PDF format, for download from:

http://www.asna.ca/alaska/research/zhizn.pdf

In addition, the 2002 Russian-language publication "Преподобный Герман Аляскинский - Жизнеописание" (Venerable Herman of Alaska - A Biography) by Sergei Korsun can be found on-line at:

http://www.russian-inok.org/books/prep_german.html