The Byzantine Empire’s long run — 1,100 years — may seem remote from the 21st century, but a reading of its history offers at least three timeless lessons. Understanding some of the fatal weaknesses in the Eastern Roman Empire may help clarify the political and economic problems that America faces today and the choices we have in responding to them.

Founded in 330 by the emperor Constantine, the eastern half of the Roman Empire was centered in Constantinople, the New Rome. By the fourth century, the empire had endured more than a century of instability, internecine warfare, and economic decline. In that context Rome’s eastern lands, arcing around Asia Minor, the Levant, and northern Africa, were especially attractive, being richer and more settled than the comparatively backward parts of western Europe. It was in part to assure continued access to these sources of wealth that Constantine relocated his capital. By A.D. 476, Rome had been overrun by barbarian tribes, and before long only Constantinople in the East had a seat for the emperors.

The first lesson for America to take from the history of Byzantium is about individualism and freedom. While it was no democracy, nonetheless Byzantium flourished when it allowed its citizens, and particularly its soldiers, greater individual freedom and responsibility. Beginning in the early 7th century, Emperor Heraclius moved from the traditional reliance on the provinces and their civilian governors and instead established large military zones, or “themes,” in Asia Minor, which was now the backbone of the empire. Centralization was maintained through the appointment of a single official with both civil and military responsibilities, but the real innovation of the themes was how the land was settled by imperial troops.

In essence, the soldiers became permanent farmers who could be called on for military service yet would be self-sustaining. They relieved the empire of the necessity of recruiting and paying expensive and often unreliable foreign mercenaries. Moreover, while becoming the most effective frontier defense the state had ever known, as individual landholders they added enormously to the productive capacity and wealth of the empire by cultivating their tracts of farmland.

Byzantium’s strength was fatally undermined when the government lost control of the countryside and either acquiesced in or abetted the formation of private landed estates. The farmer-soldiers were steadily alienated from their land, often owing to exorbitant government taxes, and became instead tenant farmers under increasingly independent feudal chieftains. This destroyed the effectiveness of the Byzantine army and also led to a drop in productivity and in tax receipts to the central government. In crushing the entrepreneurial spirit and independence of the small farmers, Byzantium weakened its economy and hollowed out its military. Eventually, politics in the Byzantine state became a competition between what we would recognize as private-interest groups, aristocrats and feudal landlords, who reduced state policy to the padding of their pockets and the settling of personal disputes.

The second lesson from Byzantium is monetary. In addition to establishing his new capital, Constantine the Great created a currency of unparalleled stability. The gold solidus, or nomisma, maintained its value and was the primary international currency in Eurasia until the 11th century.

The strength of the nomisma contributed mightily to ensuring that Byzantium was the center of world trade for nearly a millennium. It promoted economic activity within the empire. As a currency of first and last resort, it globalized the medieval world economy. Even in times of economic weakness, the government strove to maintain the value of the nomisma, which redounded to Constantinople’s political influence in moments of crisis. However, as the great feudal lords began to deprive Constantinople of land, taxes, and citizens, the government’s finances began to collapse. By the 1040s, circumstances forced the empire to devalue the nomisma. Over succeeding decades, it increasingly added base metal.

The result was devastating to the economy. Byzantium’s currency quickly lost its value and international status. As inflation flared up throughout the empire, the government introduced new coins in an effort to stabilize the monetary system. Taxes steadily increased, in part to make up for the shortfall from reduced economic activity caused by the worthless money. Merchants and taxpayers alike were gradually impoverished. For the last several hundred years of its life, the Byzantine Empire lacked both a stable fisc and a growing trade sector, which in turn led to greater competition among its increasingly powerful interest groups.

These examples lead to a final political lesson for the United States. Despite the dismissive view of historians such as Edward Gibbon, Byzantine society remained vibrant and capable of reinvigorating itself even after centuries of disorder. What doomed it was decades of bad political decisions. Specific choices by emperors and feudal leaders weakened the economy, undercut the military, and sapped the empire’s cultural energy.

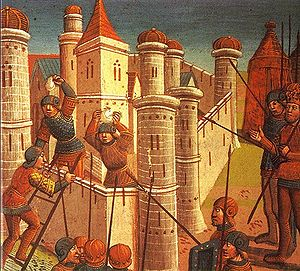

George Ostrogorsky in his magisterial History of the Byzantine State shows how the people of Byzantium rose time and again to create wealth, cultivate their intellectual capital, and achieve military success. Ultimately, though, they could not overcome the bad policy decisions that, made over the course of generations, ran counter to the proven path of political strength, cultural vigor, and economic growth. By the time Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the empire was but a shell of its former glory. For Orthodox Christians in Europe, it remained a symbol of the church, or religious commonwealth on earth, but the desolated city that greeted Sultan Mehmet II told a more sobering story of squandered wealth and misguided politics.

Michael Auslin is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

Read the entire article on the National Review Online website (new window will open).