While they were still in the secular world, and before they entered the monastery, those who were to become the Optina Elders had work experience in various areas: one managed an estate, another was a merchant, others were tailors, soldiers, or teachers. Even in our day, lessons can be drawn from the Elders’ work experience.

A group of participants in railroad construction. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1915. The holy fathers of Optina remind us that it is essential to observe feast days, and to spend them in church, at prayer. For example, while working on a feast day, Elder Isaac I (Antimonov) was threatened with mortal danger. On a certain feast day he had to weigh some merchandise, when suddenly the cross-beam from which the scales were suspended broke, and Ivan Ivanovich’s life was threatened. However, the scale beam, made of iron and weighing 600 lbs, did not hit him, but landed at his feet. From that time on, he vowed to never again work on holy days.

A group of participants in railroad construction. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1915. The holy fathers of Optina remind us that it is essential to observe feast days, and to spend them in church, at prayer. For example, while working on a feast day, Elder Isaac I (Antimonov) was threatened with mortal danger. On a certain feast day he had to weigh some merchandise, when suddenly the cross-beam from which the scales were suspended broke, and Ivan Ivanovich’s life was threatened. However, the scale beam, made of iron and weighing 600 lbs, did not hit him, but landed at his feet. From that time on, he vowed to never again work on holy days.

For over ten years, Leo Danilovitch Nagolkin, the future Elder Leo, was successful in the field of commerce. He moved about in all levels of society, and became well acquainted with their various manners and ways of life. The Lord granted that at the beginning of his journey, he might gain a treasury of life experience that would later help him in his years of eldership. What caused a successful merchant to reject a career, wealth, the joys of possibly having a family, and seek instead a life of deprivation and labor?

The Kingdom of Heaven is like unto a merchant man, seeking goodly pearls: Who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it. (Mt. 13:45). Fr. Leo found his pearl of great price. He went to God, and became the one we now know as the first of the Optina Elders.

The future Elder Macarius, then still the youth Michael, managed his estate, and from a commercial point of view, did not manage it very well. He did not strive to make a profit. Later, he was to write the following about his understanding of happiness:

“A life that is lived with a clear conscience and in humility brings peace, calm, and true happiness, while wealth, honors, renown and high position are frequently sources of many sins, and do not bring happiness.”

That is why the young man did not seek after riches, and did not chase the mirages of secular success. He read religious books, played the violin, and loved to work in a carpentry shop. He treated peasants with love, and never punished them. When they happened to steal some buckwheat from him, instead of punishing them, he instructed them with lessons from the Sacred Scriptures. Misha’s relatives laughed at him, but were amazed to see the muzhiks sincerely repent and fall to their knees before the young man.

A peasant woman pressing/softening linen. Perm Province. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 As a youth, St. Hilarion (Rodion Nikitich in the world) studied the tailor’s craft. The sensible youth, who was considering a life of monasticism, decided that such a profession would be useful to him in a monastery. He went to Moscow to perfect his craft. It was at that time that he became convinced that one should be conscientious in performing any activity; whatever you do, you should strive to do well. That is the very same rule that the Holy Fathers give to monks, whether beginners or those experienced in the spiritual life, as a condition essential to their salvation. It is what they describe in their writings as “preserving a clear conscience.”…

A peasant woman pressing/softening linen. Perm Province. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 As a youth, St. Hilarion (Rodion Nikitich in the world) studied the tailor’s craft. The sensible youth, who was considering a life of monasticism, decided that such a profession would be useful to him in a monastery. He went to Moscow to perfect his craft. It was at that time that he became convinced that one should be conscientious in performing any activity; whatever you do, you should strive to do well. That is the very same rule that the Holy Fathers give to monks, whether beginners or those experienced in the spiritual life, as a condition essential to their salvation. It is what they describe in their writings as “preserving a clear conscience.”…

At the age of twenty-four, the future Elder moved with his parents to Saratov. Not only did he strive to uphold a strictly pious way of life, he also made it a practice to have his entire work staff (about 30 people) always come to services in church on Sundays and Feast Days.

In addition, he taught his workers liturgical chant, and instilled in them the practice of singing religious songs instead of secular ones while they worked. He forbade his shop workers to engage in any idle talk or to tell any kind of indecent jokes.

Although he had a lively temperament, in all his activities St. Hilarion was distinguished by extreme gentleness, humility, and love of peace. Whenever he caught anyone—even family members—arguing, through peace-loving intervention and words of inspiration he was always able to calm the hostile atmosphere and change it to a peaceful one. He had an effect upon his workers not by instilling fear, not through threat or punishment, but rather through a variety of gentle means that affected the guilty parties’ moral disposition.

Before entering the Monastery, the future Elder Anatoly (Alexey Zertsalov) served in the Office of the Treasury. Whenever he received his wages he would share them with relatives. He was modest and strict in his way of life, and was respected and loved by all. Neatly dressed, of equable temperament, he was a comfort to his relatives whenever he visited them. His mother, who visited him quite often, would hear a great deal of praise for her son. Alexey would avoid public entertainments, was quite selective about whom he visited; and when he did call upon others, he always introduced an air of goodness and kindness.

A group of workers picking tea leaves: Greek women, Village of Chakva. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. The future Elder Barsonuphius (in the world, Pavel Ivanovich Plikhanov) went to military school in Orenburg, and then completed staff officer courses in St. Petersburg. Promoted through the ranks, he soon became a mobilization section commander, and then was promoted to colonel. Those who served with him led fast lives, consuming themselves in entertainments, while Pavel Ivanovich maintained an increasingly ascetic way of life. By his room’s simple furnishings, neatness, and multitude of icons and books, it resembled a monk’s cell.

A group of workers picking tea leaves: Greek women, Village of Chakva. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. The future Elder Barsonuphius (in the world, Pavel Ivanovich Plikhanov) went to military school in Orenburg, and then completed staff officer courses in St. Petersburg. Promoted through the ranks, he soon became a mobilization section commander, and then was promoted to colonel. Those who served with him led fast lives, consuming themselves in entertainments, while Pavel Ivanovich maintained an increasingly ascetic way of life. By his room’s simple furnishings, neatness, and multitude of icons and books, it resembled a monk’s cell.

In military service Pavel Ivanovich was considered one of the most outstanding officers, and he was not far from becoming a general, but the future Elder put attainment of spiritual heights ahead of earthly benefits. However, he did not leave for the Monastery until he had received a blessing from St. Ambrose, and he continued to serve out his term of military service. Meanwhile, in accordance with the Elder’s blessing, he donated funds to designated churches from his quite high colonel’s salary.

The future Elder Nektarius (Nicholas Tikhonov in the world) lost his father early in childhood, and from age eleven worked in a wealthy merchant’s shop. Nicholas was industrious, and by the age of seventeen he had worked his way up to junior clerk. In his spare time, the youth greatly loved to go to church and read liturgical books. He was distinguished by his humility, meekness, and purity of mind.

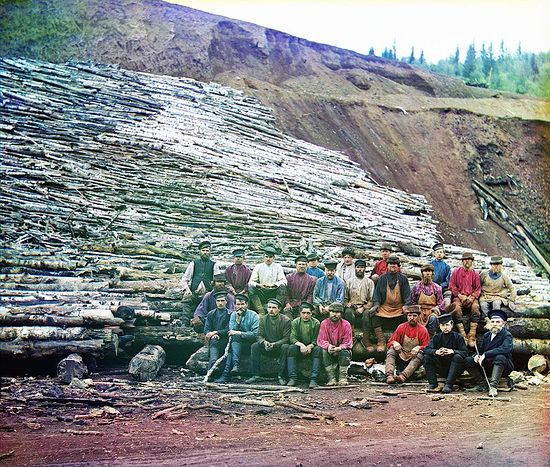

Stacking of lumber for smelting of iron ore. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 These are but a few examples from the work histories of the Venerable Fathers of Optina, but they evidence the fact the Elders labored conscientiously, striving to live in the world according to the Commandments of Christ.

Stacking of lumber for smelting of iron ore. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 These are but a few examples from the work histories of the Venerable Fathers of Optina, but they evidence the fact the Elders labored conscientiously, striving to live in the world according to the Commandments of Christ.

The Optina Elders gave advice about jobs, careers, attitudes toward co-workers, and proper performance of managerial duties. This advice is relevant today.

St. Leo strictly counseled people to adhere to the Commandments and not allow any deeds that worked against one’s conscience:

“In commercial transactions keep your conscience beyond reproach, lest you give your neighbors cause for vanity in buying and selling, and thereby bring you not imagined benefit, but great harm and spiritual vanity.”

St. Ambrose taught people to work to the best of their abilities, and to expect recompense for their labors from God, rather than seeking after human glory:

“In all things, you need to struggle to the best of your ability to aim for success for God’s sake, and to await your recompense from the Lord.”

Fashioning a mold for an art casting. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1910 St. Ambrose recommended that in choosing a job, you should take into account your age and physical and mental strengths which might be appropriate or inappropriate for a given position. The Elder also counseled that you should consider whether the job is of benefit, and examine the circumstances in which you would be working:

Fashioning a mold for an art casting. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1910 St. Ambrose recommended that in choosing a job, you should take into account your age and physical and mental strengths which might be appropriate or inappropriate for a given position. The Elder also counseled that you should consider whether the job is of benefit, and examine the circumstances in which you would be working:

“If they should offer to extend your service in the same or some other form, then first consider your years and your physical and mental strengths.

“Secondly, examine from every angle whether your work could be beneficial, even in an oblique manner. Likewise, scrutinize the conditions attendant to the job, and whether they would be favorable. Then, after considering everything, you can decide. If it can feasibly be beneficial then you should remain on the job; if not you should leave, regardless of your family’s attempts to persuade you that it would give them some outward advantage. Answer them by showing the spiritual disadvantages to you that the job would entail.”

When St. Ambrose received a letter from a spiritual child regarding complications at work, he explained that there was “disorder in the entire world.” And that the disorder stemmed from “intellectual rebelliousness and inordinate egotism.” The Elder gave wise counsel about how to behave in difficult circumstances at work; his advice is relevant today as well:

“Day by day, things on your job are becoming more complex and are making your situation more difficult. What can you do? Right now there is disorder throughout the entire world, due to intellectual rebelliousness inordinate egotism. Don’t even talk about enthusiastic people—we see that even among the most well-intentioned people it is rare to find two of like mind who get along with one another. Each one thinks in his own way, sees things in his own way, and persistently acts in his own way—when he can, openly, but more often through cunning, like a shrewd politician.

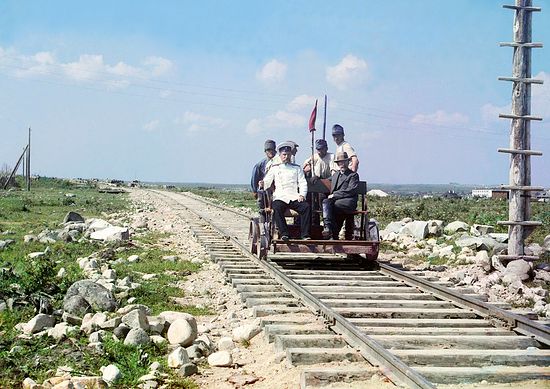

On a handcar at Petrozavodsk. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1916 “In such circumstances, may one who does not yet have complete authority constantly bring to mind the advice given by the Lord Himself: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves… (Mt. 10:16);that is, when you see someone acting unjustly, instead of becoming upset and indignant you should act wisely in order to achieve one’s goals, perhaps not in everything, but at least in the main concern, or in whatever it is possible to achieve—just as when the serpent’s body is wounded it tries in every way possible to save its head. Overall, the times are such that we have to try, at least in some respect, to fulfill our good intentions.

On a handcar at Petrozavodsk. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1916 “In such circumstances, may one who does not yet have complete authority constantly bring to mind the advice given by the Lord Himself: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves… (Mt. 10:16);that is, when you see someone acting unjustly, instead of becoming upset and indignant you should act wisely in order to achieve one’s goals, perhaps not in everything, but at least in the main concern, or in whatever it is possible to achieve—just as when the serpent’s body is wounded it tries in every way possible to save its head. Overall, the times are such that we have to try, at least in some respect, to fulfill our good intentions.

Elder Ambrose taught that you should try to adapt your manner to harmonize with the character of your colleague or supervisor, and if that is not possible, then submit to God’s will, taking comfort in the fact that the Lord sees our good intentions:

“With respect to the chief overseer, whoever he might be, you must have the following understanding: function in a way that adapts to his character. If he says one thing but expresses another in writing or in deeds, you should not seek from him a logical spoken explanation—that would be pointless. It is best to proceed and turn the matter over to the will of God. If it works, good; if not, or if it undergoes some unfair alteration, you will not have to answer for that. You should console yourself with the fact that the Lord sees your good intentions, and only demands that you do what you can; He does not ask what is beyond your power and capability.”

Monks of the St. Nilus Hermitage working: planting of potatoes. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 When St. Ambrose’s spiritual son complained about being unfairly oppressed, the Elder counseled him not to leave his position, and if need be, “not to disdain human assistance”. He told him to be prepared to suffer in a just cause for God’s sake:

Monks of the St. Nilus Hermitage working: planting of potatoes. Photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky. 1910 When St. Ambrose’s spiritual son complained about being unfairly oppressed, the Elder counseled him not to leave his position, and if need be, “not to disdain human assistance”. He told him to be prepared to suffer in a just cause for God’s sake:

“You should not leave your position… You should not disdain human assistance: you can ask two acquaintances to write on your behalf to St. Petersburg, and ask whoever they can there… If you have to suffer in a just cause for God’s sake, you should not refuse. We live for the life and glory to come, and not for the present.”

When the unjust oppression continued, the Elder consoled his child and called him not to become despondent, but to remember that the main thing was to fulfill his duty before God:

“You write first of all about your continuing battle with your opponents. Although many people approve of your actions, no one wants to help you, and as a result you are forced to carry on the battle alone. Do not despair. God is capable of giving you His assistance… If God were to allow the opposing side to overcome [you], the worst thing that could happen is that you be asked to leave your job; and by the way, I don’t expect even that. In any case, you will have fulfilled your duty before God.”

As to how to react to denunciations by subordinates, the Elder gave the following instructions:

“You should follow the middle way in dealing with denunciations—not fully believing them, and not completely rejecting them, but waiting to see what will be revealed in the matter… It is useful to call to mind the Prophet David’s advice: Commit thy way unto the Lord; trust also in him; and He shall bring it to pass. And He shall bring forth thy righteousness as the light, and thy judgment as the noonday. (Ps. 36:5–6). Read the entire Psalm.”

In response to a spiritual child’s complaints that he had been inveigled into incurring excessive work-related expenses, St. Ambrose said the following:

“It is obvious that your position tempts you to incur excessive expenses, so in order to avoid falling into debt beyond your means, you may refuse at times, at your discretion; for debts are worse than sins. A person repents of his sins and God forgives him, but they will torture you for debts both in this life and the next. May the Lord spare you from that.”

St. Nikon taught that you should not do work that goes against your conscience and your faith:

“Should your work be directly contrary to your conscience and faith, you must, of course, leave it. May the Lord help you.”

The advice given by the Optina Elders regarding work and careers is based on the Commandments of God, and therefore remains relevant today. Perhaps these words of advice may be of use to someone, and answer unasked questions.