SOURCE: Pravmir

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov), abbot of Sretensky Monastery in central Moscow and author of the best-selling Everyday Saints and Other Stories, spoke with Anna Danilova, editor-in-chief of pravmir.ru. Many of the questions concerning the state of contemporary monasticism are raised in the context of the ongoing discussion of the revised “Regulations on the Monasteries and Monastics,” submitted to the dioceses of the Russian Orthodox Church for review by a commission of the Inter-Council Presence, of which Fr. Tikhon is a member.

Fr. Tikhon, what is the primary purpose of a monastery? Should a monastery serve the world?

The primary purpose of a monastery is to help a monk leave the world and everything that is in the word in order to serve God and people for the salvation of his soul.

Is there some way to set the balance between a monastery’s outward and inward life?

I don’t know. Sretensky Monastery’s given obedience is the training of future pastors. Is this an inward or an outward activity of the monastery? Amazing fellows come to our seminary; I truly admire them. We publish books, which is an outward activity – it’s how we support the monastery and seminary. But, most importantly, this is also the spiritual obedience bequeathed to us by Fr. John (Krestiankin).

Or, speaking of inward service: does this just mean only private prayer and divine services? I don’t think that’s right.

We started building a skete in the Ryazan Oblast [southeast of Moscow] so we could get away from the hustle and bustle now and then. But there we found new parishioners, ruined churches, and even a collective farm [kolkhoz] in need of care. We had to restore the whole village, so there’d be a church with people living around it. Our new parishioners need the new church we are building. They can’t fit into the old church on great feast days, being forced to stand outside. But the brothers don’t need a large church. Is this then an outward activity?

The Holy Fathers said that a monk should do everything as service to God, even if it’s sweeping the courtyard or standing at the stove. If one goes about it like this, then such questions would probably just not come up.

And you have an orphanage in the Ryazan Oblast?

Yes, we saw a boarding school nearby and gradually began helping it. Raising children is not a job for monks – that’s ridiculous even to speak of. We do visit them as Father Frost to bring presents and we also help support them financially. The kids come to services in our church. Graduates of our seminary, married priests and their families, take care of the most important part. They have experience raising children, so they go there to guide and to educate.

I don’t see any insoluble dilemma here. For us this is all somehow normal, and it’s even strange for anyone to see a problem here.

But what if there is no charity work at a monastery – no orphanage or almshouse? Is that possible?

No charity work? That doesn’t happen. Every monastery prays for the world. That’s its main work. If for some reason a monastery doesn’t engage in what is now commonly called “charity work,” I can’t quite imagine how it would be possible to impose this from above. How would this work? A monastery is leading its life and then an order comes along: “Open an orphanage!” That’s absurd. Everything should naturally flow from the circumstances in which the Lord has placed us.

Can you compare whether it’s easier for a monastery to engage in charity work in the middle of a city or in the countryside?

The view exists that the further away one gets from the capital, the more difficult it becomes to organize aid. I completely disagree. For instance, not far from the Pskov-Caves Monastery, on an isolated farmstead, lives the handmaiden of God Eugenia. She moved there from Moscow and is raising four adopted children with Down syndrome and other serious conditions. She earns a living by painting icons. Her farmstead is exactly the same as a convent with one nun. It doesn’t matter whether she wears a skirt or a robe, a scarf or a veil. The most important thing is that she lives like a true nun – and there are plenty of people like her. We know priests who have raised fifty, seventy children. We know extremely small monasteries that help dozens of people survive.

On the hermitic life.

Can a monk go into solitude, reclusion, or even into the woods? There are sad examples, for example, of monasteries fleeing to the forests to escape the VAT identification number.

Which path is preferable: the contemplative or the active?

One’s path might be active or it might be contemplative, but the main thing is to understand God’s will for oneself. If one goes into the desert against God’s will, then one’s ascetic struggle will be for sin and perdition. And vice versa.

On God’s will

To hear, understand, and feel God’s will for oneself, and then to find the strength to fulfill this it – I think that this is the most important thing in a person’s life. I always say in our pastoral theology courses that priests and spiritual fathers have one task: to seek and find God’s will together with the person who comes to them. Don’t rush to say: “See, God’s will is such-and-such.” Rather, one needs to seek it out gradually in the various circumstances of one’s life. It is presumptuous and silly for someone to claim: “God’s will has been revealed to me!” Fr. John (Krestiankin), an Elder to whom – I am sincerely convinced – the Lord did indeed reveal His will for people, only once said to me: “This is God’s will for you.” In certain circumstances of life, finding God’s will is quite easy, because it is stated in the Gospel in the most straightforward manner. But sometimes circumstances get so tangled up that it can be very difficult to understand what one ought to do.

A difficult task…

Yes, it can sometimes be very difficult for a spiritual father to guide someone to an understanding of God’s will. It is no wonder that the Holy Fathers wrote that pastoral service is the “art of arts and science of sciences.”

Is this, generally speaking, a feasible task – given that even Fr. John (Krestiankin) spoke to you directly about God’s will only once?

He spoke about it only once, but he many times led many people to an understanding of God’s will. You’re right; it’s a difficult task. But, on the other hand, this certainly doesn’t mean that someone, along with his spiritual father, cannot understand God’s will. The Lord puts priests in a position to help lead people to salvation by God’s will. Pastors gradually, step by step, uncover the will of God alongside their spiritual children – through life itself, through Holy Scripture, through questioning more experienced people. This is a great gift of God in our Orthodox Church.

On monks and private property

Can monks own property?

You know, Greek monks don’t own any property at all. I brought a Greek translation of my book to an Athonite monastery because I wanted to give them two copies, one to the abbot and one to the monastery translator. They wouldn’t even leave them in their cells! They said that once they had read them, they would give them to the monastery library. But we should remember that Greek monks enter monasteries that have been in existence for a thousand years before them, which already have everything necessary for the monastic and liturgical life.

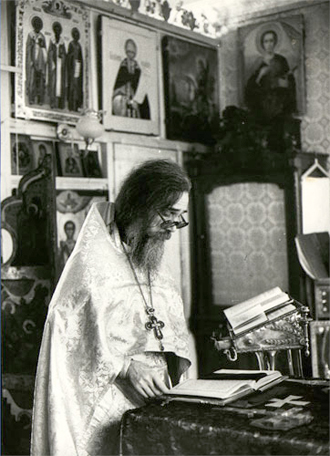

Archimandrite Innocent (Prosvirnin) (+1994).

Archimandrite Innocent (Prosvirnin) (+1994). I remember what Archimandrite Innocent (Prosvirnin) in the Publishing Department taught me: “When you become a priest, buy yourself a nice cup and saucer and draw a little cross on the bottom of both. Then you’ll have a chalice and a paten. When persecution begins, you’ll travel from city to city and serve in secret. If the KGB catches you and finds liturgical vessels, they’ll immediately seize everything. But here you just have a cup and saucer – they won’t take them away, they won’t guess!” That’s very wise, wouldn’t you say? During a search, who’ll notice a cup and saucer? But in reality it’s a chalice and paten, and the teaspoon is a liturgical spoon.

How is the issue of private property addressed in Sretensky Monastery?

Monks have their own books and icons. No televisions or tapes. If someone owned a car when entering the monastery, it is used for monastery purposes. Monks go by car to bring Communion to the sick and get supplies; they are manned by roster on Saturdays and Sundays. Many have computers. But in our rule we have special guidelines defining how they can be used. Generally speaking, half of our brothers work in book production: writing, editing, and correcting. I need to have a computer in my cell, but one of our monks who is a genius, a virtuoso in computers, doesn’t have one in his cell. There’s nothing at all in his cell, not even a bed – he sleeps on the floor.

On luxury among monks

Today the question of luxury among monastics, of expensive cars, is particularly acute…

Can anything be done about this?

I think this is a topic for a future Council. Of course, there can be complexities and even misunderstandings. For example, I take photographs for our site and our books. We have a very good professional-grade camera. It’s not mine, but if someone seems me taking photographs, they might think: “That’s quite some camera that Batiushka has!”

On monks going on leave

Should monks be able to go on leave?

As with the election of abbots, this question cannot be answered unequivocally – that either they should or should not be able to take leaves. We have monks who never go on leave. One monk goes on leave for exactly two days, travels to his patron saint, receives Communion there, and then returns. Then there are also monks with physical ailments for whom it’s simply essential that they go somewhere to restore their health, spend time in a different climate, and breathe different air. I myself have just returned from such a trip, to treat my lungs.

On the monastic typikon

Fr. Tikhon, should there be a single typikon [ustav, meaning “charter” or “rule”] for monasteries?

In the documents of the Inter-Council Presence we wrote, in principle, an approximate general typikon for monasteries – in principle, and approximate. Every monastery should adopt its own typikon at a brotherhood council, correcting whatever it considers necessary and only then submitting it to the bishop for approval. Still, there are certain basics. There is the civil statute of the Russian Orthodox Church outside of which we can’t exist. There are historically formed typika, such as those of the Yuriev Monastery in Novgorod or the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. The latter was developed in the twentieth century and is followed by essentially all monasteries of the Russian Orthodox Church. One can’t simply cast aside these typika. One can use many of them as bases, and then develop, discuss, and adopt them with the brethren for approval by the bishop.

On abbatial elections

I will immediately outline my position.

Ideally, the abbot should be elected by the brethren and confirmed by the bishop. This is how it’s done today in many [local] Orthodox Churches. This is the centuries-tested, perfectly proper way for those monasteries that have deep-rooted monastic traditions and a continuity of monastic piety and living ascetic experience that has been passed down through the generations. The classic example, cited by practically all supporters of abbatial elections, is Mount Athos, where monastic continuity hasn’t been interrupted for centuries.

I’m in complete agreement with this, but I’d like to draw attention to two not insignificant points. First, such a tradition has never been widespread in the Russian Church. Whether you like it or not, this cannot be ignored. Second, and more importantly: today’s Russian monastic communities aren’t just young – they’re in very early infancy. This can hardly be disputed. Even fifteen years ago it was fashionable to say ironically: “This isn’t a monastery, it’s a Komsomol [Young Atheist] campaign!” There was some truth contained in these poisonous, essentially unfair words: a significant percentage of the monastic brethren had been literally called by God from among yesterday’s atheists and Young Communists.

These monks are now forty, fifty, sixty years old. But at issue here, it goes without saying, is not human age, but rather the spiritual maturity of monastic communities. It’s an obvious and perfectly natural fact that not all these monasteries have reached voting age. Hence the well-founded fear that abbatial elections could result in the sorts of power struggles we’ve already discussed, that is, in confrontations between different groups, factions, and parties. And it’s hard to think of anything worse for monastery life. By the way, this even happens from time to time in Greece, in spite of all their centuries of continuity.

The latter, of course, certainly doesn’t mean that we should give up the aspiration to achieve the proper ordering of monastic life. On the contrary, we should aspire to just that. After all, the advantages of a reasonable and legitimate election are perfectly obvious: if the monastery brethren ask permission from the bishop to elect their own abbot, they thereby indicate that their candidate is not only the best and worthiest of their brethren, but that they themselves want to honor him as a father to whom they will submit not fearfully, but conscientiously. Finally, an election implies that all the brethren are prepared to share with the abbot the responsibility for the monastery before God and the Church. Aspiring towards this is indeed essential, but we also need to remember the words of St. Ambrose of Optina: “So as not to be mistaken, you should not hasten!”

Of this I am deeply convinced: before long the time will come when one monastery after another, both women’s and men’s, will receive from their bishops the right to elect their own abbots. Even the current “Regulations on the Monasteries” should certainly not exclude this.

Monks don’t need ecclesiastical awards [nagrady], but this is something that is truly desirable: that the right to participate in the election of an abbot or abbess be received from the hierarchy like a higher ecclesiastical award or recognition, since it is for the good ordering of a monastery’s spiritual life.

On the revelation of thoughts

What do you think of the practice of revelation of thoughts?

Fr. John (Krestiankin) had a very cautious attitude towards the constant revelation of thoughts in our days. He felt that not all spiritual fathers had matured to the point that they could constantly receive the revelation of thoughts. Although I know of a convent in which the abbess receives the revelation of thoughts, and their experience has been wholly positive.

In our monastery we have weekly Confession. Priests confess before every service. I am both the spiritual father of the brotherhood and the abbot. I think that this is the right thing for Srentensky Monastery today. A different approach is possible when the abbot and spiritual father are different people. That, too, can be right if it bears fruit. But we have instituted it this way with the blessing of Fr. John (Krestiankin).

Communion is very important. Many of my more conservative friends don’t support me in this, but I have seen from experience that receiving Communion four times a week – as the Holy Fathers, and Basil the Great in particular, commanded us – is a vital and very necessary practice for monks. We strive to keep to this rule, and some receive Communion less often, but basically we do so four times a week. On Thursdays we have a common service for the brotherhood, when all of us – both monks and novices – receive Communion.

Indeed, for people who have long ago been churched, their list of sins, as a rule, remains one and the same from one Confession to the next. A certain sense of formality can arise in the spiritual life. But at home we often sweep the floor and, glory be to God, we don’t have to rake the Augean stables each time. This isn’t the problem. The problem is when you begin to notice that the life of certain Christians becomes more and more boring every year. It should be just the opposite: it should become all the more full and joyful. This is what amazes me. That means that the most important thing isn’t being felt.

Should there be miracles, as in Everyday Saints?

There aren’t any miracles in that book: that’s just everyday Christian life.