SEE PART 1

4. THE FAR HERMITAGE

|

| St. Seraphim's "Far Hermitage". |

He was many times found in a state of wonder and reverential awe. Sometimes, doing some kind of work in the garden, his hoe would drop from his hand unnoticed even by him, and he would be carried in spirit to a higher world. The soul is a great mystery, and the ascetic’s life is entirely hidden in God. Not in vain was Fr. Seraphim’s goal the higher world, even during ordinary work. At first he worked the in garden, prepared the grass and stabilized the river banks. Later he also began to carry a sack on his shoulder filled with sand and stones. “I am tormenting my tormentor,” he would say of the enemy who attacks the ascetic. In the same way, he also gave himself over to the mosquitos.

This is how the Saint spent his day. On feast days he would walk to the monastery to attend the services, and in the morning he received Communion of the Holy Mysteries. He would remain in the monastery until evening, receiving those who came to him for advice or consolation. Then he would head back to the desert. During the first week of Great Lent he would stay in the monastery, not taking food until Saturday. Elder Isaiah was his confessor.

The Saint’s austere life became well-known, and in 1796 he was offered the abbacy of the Alaterinsky Monastery, and, not long afterwards, of the Krasnoslobodsky Monastery.

In both instances the saint categorically refused to abandon his heremetic way of life.

Later, the first refusal became associated with the beginning of his extraordinary ascetic feat of standing 1001 days and nights on a rock. Some authors of his Life supposed that deep in his heart he was tempted by the thought of abbatial authority and that this superhuman labor was undertaken as a result of temptations by his supposed ambitious thought.

However, it is hard to believe that such a base thought could have touched the heart of the ascetic, who had already attained communion with God. This lofty spiritual accomplishment was made at the price of a most cruel self-crucifixion. Could it be possible to suppose that even for an instant he could entertain a desire to descend from the heights to the everyday thrall of the world, and lose his “acquisition of the Holy Spirit,” obtained through his lifelong labor?

|

Fr. Seraphim answered him: “Saint Simeon the Stylite stood on a rock for forty-seven years; does my labor compare to his?” The other remarked that most likely he was helped by grace. “Yes,” the Elder replied, “otherwise human strength would not have been sufficient.” We are reminded of the ascetics’ struggles with the powers of hell in their Lives, and we recall the life of St. Anthony the Great.

After this victory over enemy powers, Fr. Seraphim was tested by the fearful vengeance of the enemy. He was attacked by robber-murderers, following his tenth year of desert life. One day as Fr. Seraphim was chopping wood in the forest, three peasants came up to him saying: “Lay people visit you and bring you money.”

“I do not take anything from anyone,” answered the Elder. But they did not believe him. The Elder had enormous strength, and had an axe besides, so he could have defended himself. But he remembered the words of the Savior: For all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword (Matt. 26:52). He put down the axe and said: “Do what you need to do.” They struck him on the head with his own axe, and blood trickled from his mouth. But the evil-doers continued to beat him and threw him into the cell, in hopes that when he revived he would show them himself where the money was. They ransacked his cell, breaking and destroying everything. Suddenly a dread fear came upon them and they ran off in terror. Fr. Seraphim regained consciousness and freed himself.

The next day, with great effort he dragged himself to the monastery all bloody, his face and arms covered with wounds, blood trickling from his mouth and ears, and several of his teeth knocked out. He did not answer the monks’ questions. After the Divine Liturgy he told Fr. Isaiah and a priest of the monastery what had happened. He suffered unendurably for eight full days, not taking food or drink, nor sleeping. The doctors examined the sufferer and found the following: the skull was fractured, the ribs broken, the chest damaged, and upon the body were several deadly wounds. At first he was conscious, but then fell into unconsciousness and had a wondrous vision: From the right side of the bed the Most Pure Mother of God came up to him, with the same Apostles, Peter and John, as in the first visitation. Raising the finger of her right hand towards the sufferer, she pointed towards the doctors on the other side and inquired: “What are you doing?” Then she looked at Fr. Seraphim and again said to the Apostles, “He is one of our generation.” The vision ended.

After regaining consciousness, Fr. Seraphim turned away the medics, giving himself over to the will of the Mother of God. He was soon filled with an indescribable joy, which lasted nearly four hours.

Toward evening he rose from the bed. At nine o’clock he asked for bread and sour cabbage. Gradually his health was restored, but the marks of the beating remained on him. He was stooped even before from chopping wood, but now he was bent over completely, and walked only with the aid of an axe or hoe. Fr. Seraphim stayed in the monastery for five months, then returned to the desert. The evil-doers were discovered, but Fr. Seraphim asked that they be forgiven. “If it be any other way,” he said, “I will go to some other place.” Fr. Seraphim forgave them, but God Himself punished them; their homes burned down.

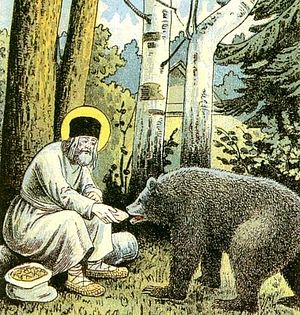

The life of the secluded desert-dweller, who had attained dispassion, was filled with unspeakable divine consolations with which God rewarded him. All creatures obeyed him. Animals from the woods streamed to his cell, and he fed them bread. He was asked where he was able to get enough food for them all. He answered that there was always enough food for them in the basket.

There was one instance when some Diveyevo nuns were vouchsafed to behold the following scene: St. Seraphim was feeding bread to a frightful bear. One of the nuns, Matrona Plescheva, was at first extremely frightened but later fed the bear herself without fear. She thought, “I can’t wait to tell the sisters about this incredible miracle.” “No, matushka,” said Fr. Seraphim in answer to her thought, “Don’t let anyone know about it until eleven years after my death.” After that period of time it so happened that she told an artist about it who was painting the Elder’s portrait, and who subsequently painted him feeding the bear.

|

Twelve years of desert life passed by. Fr. Isaiah, who had visited him before on foot, now came to him in a post-chaise. In 1807 he passed away. At that point, all of the great fathers, benefactors and contemporaries of Fr. Seraphim had reposed: Pachomius, Joseph, Mark, and now Isaiah. “They were fiery pillars from earth to heaven,” Fr. Seraphim said of them. After Fr. Isaiah’s death he entered upon a new path—the path of silence. He ceased altogether to come out to visitors. He visited the monastery less often. When they brought him his food, to the customary prayer he answered only “Amen.” He put bread or cabbage into a dish, indicating by this what he needed. Fr. Seraphim conducted this ascetic labor for three years. This was the crowning end of his seclusion. “Silence,” he said in the words of the Holy Fathers, “is the mystery of the future age.”

The sixteen-year cycle of eremitic labors was coming to an end.

5. RECLUSION

As we stated before, Fr. Seraphim visited the monastery less often as his hesychia commenced and consequently, he received Christ’s Holy Mysteries less frequently.

For him who is acquainted with the life of the hesychast, this is not strange. Thus lived St. Mary of Egypt for forty-seven years in the desert, who only at the very end of her life was able to receive Communion through Fr. Zosima.

How other desert-dwellers were able to receive the Holy Mysteries is a knowledge not open to us, for it is above normal reason and experience. St. Seraphim said to the widow Europkina, that these desert-dwellers “invisibly received Communion through Angels of God.”

Several of the monastic brothers were scandalized by Fr. Seraphim’s infrequent attendance at church services and Divine Liturgy, one of them being Fr. Niphon, who differed in spirit from Fr. Seraphim. After conferring with some of the older brothers, he decided to propose to Fr. Seraphim that, provided he is healthy and his legs strong, he should come to the monastery on Sundays and feast days as he did before and receive the Holy Mysteries. If his legs are not serving him, he should return to the monastery permanently and remain in his cell.

This decision was delivered to him through the brother who brought him his food. Fr. Seraphim silently heard him out, and lowered his eyes without uttering a single word.…

After the fifteenth year of silence it was not easy for him to abandon his hesychia and return to the monastery. The decision was difficult indeed. His behavior was understandable—having heard the brother’s message in silence, he saw him off without even opening his mouth. The next week the brother, having brought the Elder’s food, repeated the Abbot’s orders. This time Fr. Seraphim, still silent, complied with his orders and, without uttering a word, followed the brother to the monastery.

When he stepped through the monastery gates, the Elder, without going to his cell, set off straight for the infirmary. This was the afternoon before the evening service. When they rang the bells, Fr. Seraphim appeared in the church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God. The next day, May 9, the feast day of St. Nicholas, he went to the infirmary church for early Liturgy and partook of the Holy Mysteries. After Liturgy he visited Abbot Niphon, received his blessing, then secluded himself in his former cell.

Now he had to take upon himself an even more severe podvig of silence. After that he did not receive nor speak with anyone.

Of his podvig in reclusion there is even less known than of his previous desert life. In his cell there were no more than the bare necessities of life. An icon with a burning lampada before it, and a stump of wood that served as a chair were all that the cell contained. He did not even use fire or heat. He wore a heavy iron cross which some called chains. Actually, he did not wear chains and did not recommend wearing them. “When we are offended by someone’s words or actions, and we bear the offense as is written in the Gospels, this is our chains, this is our hair-shirt,” he said. In the Diveyevo Convent, however, the opposite tradition was observed: the wearing of chains was allowed.

His drink was water, and his food was either oat flour, or chopped white cabbage. His water and food were brought to him by brother Paul, who lived nearby. Sometimes the Elder would remain without food.

During the course of all his years of reclusion, the Elder received communion of Christ’s Holy Mysteries every Sunday and feast day. By Abbot Niphon’s blessing the Heavenly Mysteries were brought to him in his cell from the hospital church after early Liturgy. On regular days the brother-sacristan brought him a piece of the antidoran after each Liturgy.

His labors of prayer were great and varied. As in the desert, he conducted his regular rule and daily services, except for Liturgy. Above all he practiced mental prayer and the prayers to the Mother of God without ceasing. Sometimes he would become immersed in deep, continuous mental concentration: he would stand immobile in front of the icons, without making prostrations. In the course of one week he would have read the entire New Testament from beginning to end. He would give a discourse out loud on the Acts and Epistles of the Apostles, the door of his cell sometimes standing open, and many would come and listen to his mellifluous words.

The Tambov hierarchs would visit Sarov on the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God. In 1813 Bishop Jonah wished to visit Fr. Seraphim, but was not admitted by him. Abbot Niphon wanted to break through the door, but the Bishop said, “Wouldn’t it be a sin?” and left the monastery.

But the time of reclusion was already drawing to a close. According to some information from the Diveyevo convent, just as at the beginning of his podvig, the Mother of God appeared to him, this time with Sts. Onuphrius and Peter of Mount Athos, and directed him to end his reclusion.

Soon after Bishop Jonah’s stay at Sarov, the Tambov Governor A. M. Bezobrazov and his wife came, and the Elder opened his door to them himself to give them a blessing. This was on September 13, 1813.

At that time a new five-year period began during which his reclusion relaxed, when Fr. Seraphim began to make exceptions for some people whom he would hear and instruct.

The recluse would devote some time to physical labors. In his cell they would take the form of full prostrations; how many of them he made only God Himself knows. Sometimes at night he would secretively permit himself to leave the cell, in order to perform some kind of labor in the fresh air.

One day a brother whose obedience it was to wake the others, having arisen early in the morning, saw the recluse in front of his cell. Barely audible, pronouncing the Jesus prayer, he was carrying a billet of logs closer to his cell. Overjoyed by the vision of the holy elder, the novice threw himself at his feet, kissing them, asking for a blessing. “Go in silence and be heedful of yourself,” Fr. Seraphim said to him, and having blessed him, he hid himself in his cell.

For remembrance of the hour of death Fr. Seraphim made himself a coffin and placed it in the foyer, asking the brothers that they bury him in it. This was in time actually fulfilled.

During the time of reclusion he had a wondrous vision, when, like the Apostle Paul, whether in the body or out of the body, he was taken up to the heavenly realm. This is how he described it to the novice John Tikhonov: “Now I will tell you about poor Seraphim! One time, while reading in the Gospels of John the words of the Savior that in His Father’s house are many mansions (Jn. 14:2), I, a poor one, stopped at this thought and wished I could see the heavenly dwellings. Five days and nights I spent in vigil and prayer, asking the Lord to bless me with that vision. And the Lord, truly, in his great mercy did not withhold the consolation of my faith, and showed me those eternal shelters to which I, a poor wanderer upon the earth, momentarily ascended, (in the body or out of the body I do not know). I beheld inscrutable heavenly beauty, and those who lived there. John the Great Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord, the apostles, saints, martyrs and holy fathers, Anthony the Great, Paul of Thebes, Sabbas the Sanctified, Onuphrius the Great, Mark of Ephesus and all the saints dwelling in unspeakable glory and joy, which eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love Him (I Cor. 2:9).”

“With these words,” writes Tikhonov, “Fr. Seraphim became silent.”

“At this he leaned forward a little, his eyes closed and his head inclined to one side, and raised the palm of his right hand to his heart. His face gradually changed and gave forth a wondrous light, and finally became so bright that it was impossible to look at him. On his lips and in his entire expression was such a heavenly joy and ecstasy that truly he could be called an earthly angel and heavenly man. During his mysterious silence, he, as though contemplating something with tender feeling, listened to something with awe. But what exactly uplifted and sweetly filled the soul of the righteous one, only God knows.

“After a prolonged silence, Fr. Seraphim resumed speaking. Sighing from deep within his soul, with a feeling of inexplicable joy, he said to me:

“Ah, if you only knew what joy, what sweetness awaits the souls of the righteous in heaven, you would be determined during your life to bear any offenses, persecutions or slanders thankfully. If this entire cell were filled with worms, and if these worms ate our flesh throughout our entire lives, then with all our desire would we consent to bear it, just so that we were not excluded from the heavenly joys that God has prepared for those who love Him. There is no sickness nor sorrow, nor sighing; there is sweetness and joy unutterable, there the righteous shine like suns.… But if the Apostle Paul himself could not describe heavenly glory and joy, then what other human tongue could describe the beauty of the dwelling place wherein are established the souls of the righteous?’”

He told the same thing to A. P. Europkina, recalling to her the holy martyrs, the beauty of St. Theodosia and many others who dwell in unspeakable glory.

“Ah, my joy,” he exclaimed, “there is such blessedness that it is impossible to describe it.”

“His face,” she wrote later, “was uncanny … through his skin penetrated abundant light … his eyes expressed not only peace, but also a sort of extraordinary ecstasy. One can only suppose that even while speaking of this contemplation, he was in a state outside of visible nature—in heavenly realms.”

But now the time of reclusion was running out and nearing its end. The time had come for him to embark upon a new, higher ascetic labor—higher than anything else in the world—the labor of love, the service of saving human souls.

As soon as access was opened to the extraordinary God-pleaser, the crowds poured in.

According to the words of the Savior: Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house (Matt. 5:14). It was impossible to restrain the flood of people who came. Everyday there appeared in Sarov from 1,000 to 2,000 pilgrims.

Such a state of affairs could not but frustrate Abbot Niphon. “When Fr. Seraphim lived in the desert,” he said, “he closed off all access to himself by means of the forest, but now he is receiving everyone, so that I can’t even close the monastery gates until midnight.”

Many said to Fr. Seraphim: “Some are scandalized by you.”

“I am not scandalized, that many are helped, while others are scandalized,” the Elder responded calmly.

But they were particularly scandalized by Fr. Seraphim when he took upon himself the care of the Diveyevo sisters. They began to watch him. As a result of the calumny thrown upon the Saint the Abbot received an order from the Tambov diocesan authorities to conduct an investigation of Fr. Seraphim’s activities, and this investigation was carried out by the monastery treasurer, Fr. Isaiah. Of course, they could find no transgressions. But even so, they were unable to understand the heights of the Saint’s dispassion. Yes, he was dead [to the world], but the living could not comprehend it.

Understanding this, Fr. Seraphim, by the orders of the Mother of God, decided to return to the desert, where he could freely carry on the apostolic work of saving souls, but first of all, to build unhindered “the domain of the Mother of God” —Diveyevo Convent.

So, on the morning of the twenty-fifth of November, 1825, Fr. Seraphim left his cell and headed over to Fr. Abbot for a blessing to withdraw to his former far hermitage. Fr. Niphon blessed him, and the Elder set out through the forest.

|

| St. Seraphim's spring, today. |

Fr. Seraphim decided to dig a well over his healing spring, and completed it by his own labors. Having dug out the well, he built a frame around it and filled it in with stones. The well came to be known as Seraphim’s well. The Saint told monk Anastasius to pray to the Mother of God, and ask her to make the water in the well capable of healing diseases. “And the Mother of God,” he added, “promised to give the water a greater blessing than that of the Bethesda waters of Jerusalem.” The healings were not slow to begin. Diveyevo sister Paraskeva Semyonovna was sick and coughing. “Why are you coughing … stop, enough!” Fr. Seraphim said to her. “I can’t, Batiushka!” she answered. Then Fr. Seraphim scooped up some water with his sleeve and doused her with it. The illness immediately left her, and never returned.

|

| Inside St. Seraphim's "Near Hermitage". |

At four in the morning, and sometimes earlier, Fr. Seraphim left the monastery and went to his new living area, where he stayed until 7:00 or 8:00 in the evening. After that, he would return to the Monastery for the night. From then on, by the will of the diocesan superiors, he was to receive Communion in the church on Sundays and feast days. In the morning, when he left for the near hermitage, the crowds streamed after him. At times the Elder would hide himself. But it would sometimes happen that he would receive the visitors to the forest cell and conduct them in. Also it would happen that the people, sinking to their knees, would pray with him in the forest before the icon of the Mother of God, affixed to an ancient pine tree. Sometimes he would go to the far desert, and he would call some of them to see him there, the closest of all to him being his “orphans”—the Diveyevo sisters whom he instructed.

In the last years of his life, the Elder intensified his ascetic podvigs, even though he had already achieved dispassion. He never slept uninterrupted, and now he struggled even harder against nightly repose. As he approached his death, he began to sleep in such uncomfortable positions that it was impossible to look at him without alarm: he knelt down and slept with his face to the floor, on his elbows, supporting his head with his hands. Such a difficult podvig can only astound. St. Seraphim said: “I am tormenting my tormentor.” Such a podvig was seemingly beyond human strength.

From St. Seraphim Wonderworker of Sarov and His Spiritual Heritage by Helen Kontsevich (St. Xenia Skete)