In the year 1937, the Stalin regime carried out unrelenting, swift, and utterly draconian “purges” of all potentially “anti-soviet” elements. With Nicholai Yezhov as NKVD chief, the purge began with the show trials of old-guard Communists whom Stalin perceived as a threat to his power, and swept out over the entire country, taking with it over a million innocent victims in the span of a year. The foreign press remained long in denial about the torture, execution, and imprisonment of people in the USSR, and to this day only a few who fell into this grinder are remembered by name outside of Russia.

The Russian Orthodox Church in 1937 saw the arrest of 85% of its clergy, along with thousands of unknown laymen and women. This was the year that saw most of the executions at the Butovo firing range—a site that now has a church standing as a memorial to those victims.

* * *

It is hard to imagine now how it could have been then. In the protocol of the interrogation of one witness in the case of a priest is written: “There is information that all the clergy in Perm have been arrested and there are no [church] services anywhere…”

In 2012 the legal “statute of limitations” of 75 years ran out, and researchers were given access to the investigation archives from 1937, including those of the Perm state archives of recent history. There was a year of familiarization with the archives: searches, systematization and processing of materials, making contact with the fate of people swept away by the wave of the “Great Terror”. Of course, is not possible to encompass everything in such a short period of time: not only were clergy and parish workers brought to trial during the Yezhov period but also ordinary laypeople, called to the NKVD as witnesses and accused. For the diocesan department of the history and canonization [of new martyrs], the cases of priests and others serving in the church were singled out first. Only the “first cut” has been taken to date—the preliminary results.

General research on the theme of the “Great Terror” [also known as the Great Purge. —Trans.] of 1937 in Russian historical science has been conducted for over twenty years now. To the extent of its development, an area has been distinguished that concerns repressions against the Russian Orthodox Church and its existence under conditions of semi-legality. Information on the places of mass execution (such as the Butovo field) have entered into scholarly use, martyrology and lives of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia have been compiled.

The sentences became tougher in 1937, when 132 out of 175 cases ended in the resolution: “Execution by shooting.” If in 1932–1935 the typical punishment for article 58-10 [Anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary propaganda and agitation—the usual accusation against believers.—Trans.] was exile, and less often a three to five years of the Gulag, in 1937, convictions according to the same statute the prison sentences were more severe: “ten years of correctional labor camp.”

The character of the interrogations also changed. In 1937, the NKVD initiated larger collective accusations, including from one to ten priests. The records could comprise anywhere from thirty pages to ten volumes with three appendices (around 3000 pages). During 1932–35 there was at least a format, some semblance of a systematic “investigation”. But in 1937 a conveyor belt was switched on. Sometimes the “investigation” would last a week, in one case, only a day. One eloquent detail on the processes testifies to their rapidity (and cruelty): almost all the cases are “blind”, with only isolated records including photographs of the accused. That torture was used can be gleaned easily from the fact that in 1939 and in the 1950s, former NDVD officers were tried for the use of unlawful interrogation methods.

Modern researchers cite as one reason for the “Great Terror” the results of the January census, which showed that despite all the concerted efforts of atheistic propaganda, 56.7% of the nation’s population considered themselves religious believers. Another reason was the coming elections of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, due in December. The central terminology of “purging” the “class enemy” elements had to be fulfilled by then; and the basis of requests for the raising of execution limits was the formula: “having in mind the upcoming elections.” Truly, the data from the local archives fit this description. In Perm, repressions against the clergy peaked in late summer, early autumn of 1937.

Researcher Father Alexander Mazyrin’s thesis also shows that the state was changing its strategy from provocation against, and schisms within the Church to its total destruction. It was no longer a case of Tikhonites vs. Sergianites. People from the so-called Living Church, used by the state as a sort of “battering ram” against those loyal to Patriarch Tikhon, also found themselves among the accused, as did Old believers and other sects. Cases against former “secret police colleagues” working within the Church can even be found.

But behind the outwardly formalized characteristics is revealed a living history in between the lines of faith and faithlessness, the podvig of a confessor and blindness, courage and human weakness.

By 1937 an entire generation had grown up in an atmosphere of militant atheism, and witnesses were more easily coerced, or even came forth voluntarily against members of the clergy. The pervasive propaganda of “sabotage” and “wrecking” made people extremely fearful for their own lives, and many caved under the pressure to “bring the obscurantist priests into the light of soviet progress; to rid the nation of that vermin.”

How they conducted themselves, or, a little about the “counter-revolutionary goats”

It is almost impossible, based upon the protocols of 1937 in many cases, to picture the spiritual countenance of the people who were interrogated. Some case records were obviously manipulated: the page numbers were changed more than once (the original page numbers were crossed out or erased). As for their appearance, their service; about what one or another of them was forced to endure (and some of them are already glorified among the hosts of New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia)—more detailed information can be found from the records of the early 1930s. The stages of a priest-confessor’s path before World War II and the first years of collectivization are more clearly outlined in them. 1937 became the “final frontier” for many of them.

Just the same, regardless of the “compressed” nature of the material in the investigative archives from 1937, certain details stand out, and in some, you can hear an open confession of faith.

Who knows if the photographs of the face of a priest from the village of Ilyinskoe, Fr. Symeon Subbotin will someday surface for us to view? From the records we can imagine a self-restrained man who had to endure very much in his lifetime, but who nevertheless found the strength to answer the ridiculous accusations made against him at his final “judgment seat” in the same “tone” as his interrogators, with a dash of humor. We know from the records that the church was closed and that the sixty-eight-year-old “priest does not serve, but lives off of other people and is corrupting the collective farm.” Batiushka was one of the “former ones”, with the background of a teacher in a local school and a clerk at the village administration, who was arrested and tried in the early 1920s, but acquitted for lack of evidence. Now he was finally faced with “factual accusation”: “There were incidences when your goats caused damage to the collective farm by eating the winter crops and trampling them.” The accused answered: “From the political point of view, this is clearly a case of sabotage, and cannot be interpreted otherwise!”

Whether they took “additional measures” against him, or Fr. Simeon simply considered hypocrisy undignified for a man of his years, we don’t know, but when questioned about his view of Communist party politics he answers plainly: “The Soviet government does not rule rightly.” The final result of the ruling by the “troika” of 16/XI–1937: “Subbotin, Simeon Petrovich is sentenced to ten years of correctional prison camp. Right after that follows the announcement: “30/XI–1937 departed for Kargapol camp, NKVD. No further information on his fate.” Information is discovered significantly later at an inquiry by his family in 1956: “Prisoner S. P. Subbotin, born 1869, died while serving his prison term in Kargapol camp on January 3, 1938, from paralysis of the heart.” The investigator who conducted the interrogation was fired from the “organs” in 1953, and Fr. Simeon was rehabilitated in 1958, posthumously.

We also meet amazing examples of courage, when the accused did not deny the witness’ testimony against them, but refused to “collaborate” with the investigation, knowing well that every word could cost someone else’s life. One example is Fedor Vasilievich Bakhmatov—that is his name on his documents. “Informers” have shown that the accused is a priest of Tikhonite orientation, a hieromonk. His personal information is sparse: born 1874, lived the Yusvensky region of Komi-Perm district, began serving before the revolution, in 1915. Nothing is written about his monastery or places of service. He does not deny the accusation against him that he had no permanent place of work, and of “walking from village to village and baptizing, not having permission to do so”. The interrogators were trying to get from him and several other priests information on the activities of a mythical “unified counter-revolutionary organization”, according to an NKVD-devised “pyramid” scheme. The larger “targets” in this case were Bishops Gleb (Pokrovsky) of Perm and Peter (Saveliev) of Sverdlovsk, and the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky). But they were able to “squeeze” only one thing from him: “Declaration. The investigation demands that I admit to participation in a counter-revolutionary organization of Church representatives. I categorically declare that I will not give any testimony. F. Bakhmatov. October 27, 1937”.

At every turn of the interrogation, he repeats, “I know nothing about any organizations and have not heard about them from anyone”; “I will not answer that question, and request that no more such questions be asked.” Nevertheless, in the “plan” processes of 1937, imprisonment did not depend upon acknowledgment or non-acknowledgment of guilt. The sentence was determined according to the factors at hand—the conjuncture of the investigators’ “clairvoyance” and the informers’ “loquacity”: “Bakhmatov, F. V. is an active participant in a counter-revolutionary fascist insurgent organization of churchmen. Fulfilling the tasks of the c-r organization and not occupied with socially beneficial labor, he went from village to village, baptized adults and children, and conducted c-r agitation. He gathered espionage information about the economic and political condition of the collective farms and the population’s disposition. He refused to give any indication of his participation in c-r fascist organizations. He pleads not guilty, but he has read the testimony of (the names of the witnesses are written).” At the end of the records is the decision page—the sentence of the Troika on 2/XI–1937: “Execution by shooting. All personal belongings shall be confiscated.” The execution was carried out on November 10, 1937. In 1989, an order of rehabilitation was attached.

Of course, historians and archivists have their own attachments when it comes down to familiarizing themselves with the records of repressed priests, and they are usually the already canonized martyrs for Christ, or “candidates” for canonization.

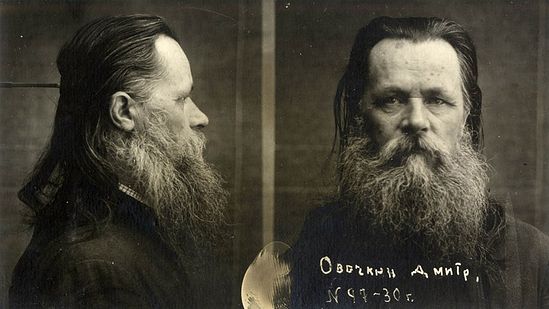

Priest Dimitry Ovechkin. Photo from the investigative records, 1930.

Priest Dimitry Ovechkin. Photo from the investigative records, 1930.

Holy hieromartyr Dimitry Ovechkin was a typical village priest who served in the Church of St. Procopius in the village of Kuznechikha, Osinskoe region. He was born in 1877 to a peasant family. Probably he had to make no small effort to receive his education in the Kazan seminary. He was ordained a priest at age 32. Bishop Palladius ordained him in 1909. Father Dimitry began his “way of the cross” in 1922, when he refused to participate in the commission for the confiscation of Church valuables. He was then given a commuted sentence of six months imprisonment, but in 1930 he was given a real term of three years in concentration camp, accused of “organizing a protest against events conducted by the Soviet government”. In the year of the “Great Terror” he again came to the attention of the NKVD. People were found who agreed to testify against him: he supposedly talked about the crop failure and famine enveloping Russia, about the extremely difficult conditions of life when he, a priest, could not get a job (Father Dimitry had a wife and three children to support), and about how the party administration was turning people’s attention away from the economic problems by staging the spectacles of trials according to plan. What of this was true and what was contrived? The main thing is that witnesses were found to testify.

In the application form for the record of 1937, one detail noted by the interrogator draws our attention: “A cross is tattooed on his chest.” Apparently he had experience—baptismal crosses were confiscated in the camps. The protocol fixes the unrelenting tone and tense atmosphere during the interrogation: in connection with other persons under investigation, Father Dimitry does not confirm any conversations on political themes, or the existence of a “counter-revolutionary organization. He has nothing to convey. The interrogator screams in his face, “You’re lying!” But Fr. Dimitry only replies quietly, “I have given truthful testimony and cannot add anything else.” Again, “You’re lying!” The interrogator reads the testimony of other persons under investigation about supposedly “recruited members of the organization.” To every “Do you confess?” Father Dimitry only repeats, “I do not confess to it.”

Seven people were arraigned in this case. Two of them, Father Dimitry Ovechkin and Father Nicholai Uvitsky, were sentenced on November 4, 1937 to “execution by shooting.” On November 14 the troika executed the sentence. But Father Dimitry’s relatives had no reliable information about him for many long years. Even after Stalin’s death in 1957, when his widow made an inquiry she received a flagrantly false answer according to the existing formula: “Ovechkina, Olga Grigorievna is to be told orally that Ovechkin, Dimitry Kiprianovich was sentenced on November 4, 1937 to ten years of corrective labor camp, and died in his place of imprisonment on December 5, 1941 from pellagra. His death should be registered in the Osinskoe registration office.”

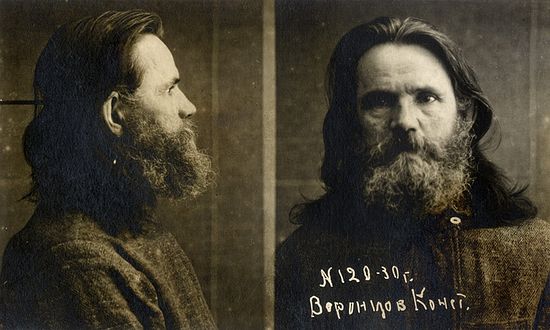

Of the particularly memorable cases was the story of priest Constantine Voronstov. He was an amazing priest. During the civil war period he acted as a true peacemaker according to the Gospels, merciful toward those who suffered or who found themselves under the threat of danger. In 1919 he was first arrested for “counter-revolutionary agitation”. Those who composed the accusation in the local Cheka had been especially zealous, describing how the priest had served Pannikhidas for the White Guards who were killed or died in the “Red” prisons, and how he had called upon people in his sermons to “remember God’s commandment to love one another, so that the war would end quickly.” Father Constantine would not have escaped execution then if “guarantors” had not come forward on his behalf—Communists, members of the executive committee, who testified that when the “Whites” were in power Batiushka had visited them in in the Okhansk prison to give them food; he gave some of them shelter at his own home, and saved very many from sure death by his pastoral intercession.

This was not an easy, straightforward situation. The Cheka thought and thought about it, then declared, “For c-r activity, Voronstov is to be imprisoned in concentration camp for the entire period of the civil war without right of amnesty, with the institution of forced labor…” Nevertheless, ten days later, apparently under pressure, they changed their minds and released him “on bail”, two months later giving him full amnesty.

Ten years passed and everything took on a different color. In 1930, “signals” began to come to the OGPU from his fellow villagers informing that “Priest Costya is telling people not to attend meetings and shows, he doesn’t bless girls to marry Komsomol members, and is agitating against joining the collective farm.” No guarantors were found this time, and Father Constantine was given three years of concentration camp.

Priest Constantine Vorontsov. Photo from investigatie records, 1930.

Priest Constantine Vorontsov. Photo from investigatie records, 1930.

In comparison with the earlier cases against him, the 1937 case against Father Constantine appears brief. He is entered as participant of secondary importance in the proceeding. There is only a form and one investigative protocol in the documents on him personally. In the accusatory conclusion, the testimony of “informers” about how Father Constantine is supposedly a “member of counter-revolutionary groups” who are preparing to sabotage important targets (these legends were born of torture and fabrication, as we can surmise from later information), “conducts anti-soviet conversations,” “assumed the functions of the registration office” [a reference to marriages and deaths.—Trans.], and “intentionally held worshippers in church until 11:00 a.m.” Father Constantine Voronstov did not plead guilty; nevertheless he was sentenced to ten years of corrective labor camp by a “troika”. He was rehabilitated in 1989.

And here is a very brief story of a hitherto unknown confessor, the village priest Yakov Noskov from the village of Vereino, Verkhne-Gorod region. This time a seventy-year-old elder stood accused. He was from the peasantry and possessed an elementary education. In 1929 he was given two years of incarceration and five years of exile for not paying grain taxes. In 1937 he fell under the “plan purges”.

You don’t always see such a clear example of confession of faith behind the political form of fabricated cases in 1937. The following is from the protocol of Father Yakov’s interrogation: “I consciously went to serve the Church; I wanted to replace the priests who died for the Christian faith, executed by the Soviet authorities. <…> I decided that my place should be among the ranks of those who struggle for the Church and for religion, and in 1926 I began my service. <…> I urged the faithful not to allow the closing of churches. No matter how long the Soviet authorities might humiliate us and blaspheme, the time will come when we will again see a happy life.”

He does not name any names, but he reminds them that when one of his villagers warned him to hide temporarily, he answered, “Let it be as it will be. Where can one hide?” and adds, “Let them shoot me, I am not afraid. <…> If I suffer at the hands of the Soviet authorities I will receive a reward from God: paradise.”

In his simplicity Batiushka admits that he conducted “counter-revolutionary conversations” with collective farm workers, and immediately explains that he did not call them to resist or overthrow the government, but only said the following: “The Soviet government is pushing us into paradise. <…> God alone knows when the Soviet government will fall. When God sees our righteous works, perhaps He will send us deliverance. <…> The Soviet government was given to us for our sins.”

In the protocol from the session of the “troika” is written: “Sentenced to execution by shooting. Personal belongings shall be confiscated.” Further, “Sentence executed on 20/IX–1937, at 24:00.

When in 1989 the case of Father Yakov came under the Order of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of January 16, 1989 “On supplementary measures for the restoration of justice with respect to victims of repression that occurred in the 1930s—1940s and the beginning of the 1950s,” his relatives were given the recommendation to present for his rehabilitation a letter about his death that occurred “for no indicated reason.”

* * *

By the summer of 1938, the Great Terror had become so massive and claimed so many victims that the brakes were put on, and Yezhov himself was relieved of his duties and eventually purged. Also arrested were many of the NKVD officers who fabricated accusations and used torture to extract confessions of guilt. These included a number of NKVD officers in Perm, also. Later years would bring the official “rehabilitation” of unjustly sentenced victims.

But historical fairness is a relative thing. The relatives of the victims had to go through years of petitioning one office after another, receiving evasive answers, half-truths, and in some cases “consolations” worthy of note.

Among the repressed clergy in Perm diocese in 1937 was Father Joseph Kalashnikov from Ananina, Chernushinsk region. It was the standard accusation: “Participation in a c-r organization.” Sentence to execution and confiscation of property were pronounced by the NKVD “troika” on September 25, 1937. The records also state that the sentence was executed on September 27, 1937. In 1958, Father Joseph was rehabilitated posthumously. At the widow’s inquiry an answer came according to instructions: “While in his place of incarceration, he died on January 26, 1944 of a stroke.” A few years later came the “satisfaction” of his widow’s request for compensation of the confiscated property: “Total reward from the soviet budget is 46 rub, 59 kop. (forty-six rubles, fifty-nine kopecks). This was the price of a pair of shoes. It was 1964; a widow, the mother of five children…

* * *

Twentieth century Russian history was built upon contrasts. Even today, some venerate the New Martyrs, while others, alas, are still “outstanding fighters against the treachery and sedition” of the period in the 1930s. Of course, studying the fates of those who suffered for their faith should not become a cause to stir feelings of revenge. Both erudite and simple; meek, yet often rebuking their torturers during interrogation, they were aware that they were becoming sacrifices for the One Whose name is Love, and firmly believed that “the gates of hell will not prevail against the Church”. They hoped only that time would bring a good memorial of them. It is important to know about this and not to confuse anything…

The authors express their sincerest thanks to the colleagues of the Perm governmental archives for the help provided in their work with archival documents.