May 13, 2013, marks the twelfth anniversary of the martyric death of Priest Igor Rozin on the feast day of St. Ignatius, Bishop of the Caucasus, in the city of Tyrnyauz in the North Caucasus.

One cannot drive to the foot of Mount Elbrus except through Tyrnyauz. The road from the city takes a rapid turn upwards until it reaches Terskol. There it ends: above that, one can proceed only by cable or on foot.

There is, however, one more way: from the north, from Kislovodsk, on a mountain road. That is the way that stubborn mountain climbers took when the road through Tyrnyauz was closed for nearly an entire year, from February to November 2011, when a counter-terrorist operation was underway here. Today this operation is often still declared, but not for long: usually for a day or two, during which the news shows stories of how a cache of explosives was located or an apartment in which militants were entrenched was stormed. Few people outside of Tyrnyauz pay attention to this news: today television shows too much of it. But it is another story when you live here. People entering the city encounter roadblocks. Resting his elbow on the butt of a machinegun hanging from his chest, a solider in body armor smokes next to an armored personnel carrier. A black mask covers his face. Other gunmen beside him check the Soviet-era cars parked at the roadside.

In the distance one can see the empty-eyed skeletons of buildings belonging to the Tyrnyauz Mining and Ore-Dressing Integrated Plant, which was once famous throughout the entire Soviet Union. In the beginning of the 1930s tungsten-molybdenum ore was discovered and the city was built, but the plant began to fade in the early 1990s and has since completely shut down. This once flourishing garden city has been plunged into poverty and desolate chaos. But what has not been taken away from this place is the beauty of God’s world, which shows through the distorted features of modernity.

The unusual, almost radiant air gives the landscape a certain unreality – perhaps this is a quality of the mountain, or perhaps of this place. The velvet sides of the mountain, the ragged cliffs, the grey peak of Totur, looking down on Tyrnyauz, the eagles pumping their wings in the air currents – everything is so beautiful that it is as if you were in one of the fabulous countries you read about as a child.

To the right, on the mountain slope, one can see the city cemetery. Over one of the graves is a tall canopy topped by a cross. It was installed recently, a couple of years ago, as was the black marble cross, now hugged by a viburnum bush. Before this, the grave of Priest Igor Rozin looked like almost all the others, with the exception that beyond its fence, both then as now, one could often see people praying.

Despite the fact that getting to Tyrnyauz is not easy, and not always without danger, people come to Fr. Igor’s grave constantly: from the Caucasus, from Moscow, from St. Petersburg. We drive into the city. The winding road, making its way through the new region, finally becomes an avenue that is straight as an arrow.

+++

In the Soviet years, as it still is today, it was called Elbrus Avenue. Commander Igor Rozin of the avalanche squad, a rescuer and mountain climber, travelled on it more than once. Priest Igor hurried the same way from Terskol to services. He was ordained in 1999, being given the only surviving building from 1937 as a church. “Once I happened to meet him—I hadn’t seen him in a long time. He asked if I could restore an old Bible for him. I was surprised,” related Dmitry, a neighbor of the Rozin family in Terskol and a colleague from the Vysokogorny Institute. “And he said: ‘I’ve become a priest.’ ‘Where?’ ‘In Tyrnyauz. We were given the dirtiest place in the city.’” Is that what he really said: the dirtiest place? “That’s what he said. In fact, it was dirty: a bacteriological laboratory. It couldn’t have been any dirtier: they brought all the diseases there. But he said: ‘We’ll pray away this dirtiest of places: nothing’s impossible.’”

I still think that he put it differently: all things are possible to him that believeth [Mark 9:23].

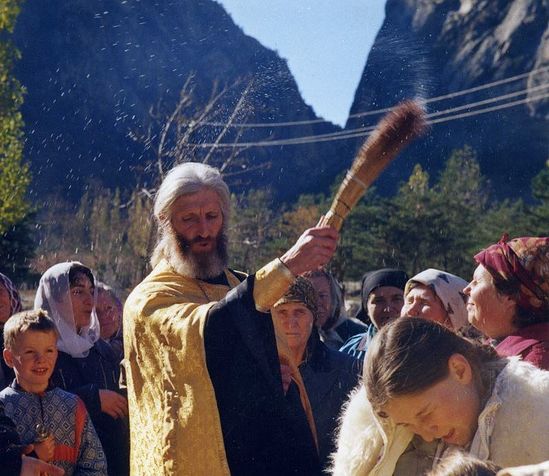

They did indeed clean and pray away. The entire community took care of the repairs: there was neither a window, nor a door, nor a floor. There is a photograph in which the first rector of the first church in the history of Tyrnyauz, Fr. Igor Rozin, is captured along with the dean, Fr. Leonid, and his daughter.

Behind their backs is an icy metal porch, painted blue, the same color as the decrepit door with its homemade cross welded together from thin pipes, and a gray and peeling wall. The word “church” is written in large, solemn letters on the nameplate. Fr. Igor is just barely smiling under his moustache. The inscription on the photo reads: “Tyrnyauz, ‘cathedral,’ Fr. Igor.”

Not many photographs of him are left. But if one puts them in chronological order, the dramatic change he underwent towards the end of his life of forty-five years becomes obvious. Mind you, the term “dramatic change” comes from the other, worldly vocabulary of his first, pre-Christian half of life.

For the second, short, but utterly beautiful part, an entirely different word is appropriate: Transfiguration.

+++

He served out his entire, short priestly life—less than two years—in this church. “It was very hard for him spiritually, because this was an unsanctified, unconsecrated place. This was a demonic area,” says Hieromonk Igor (Vasiliev), then Fr. Igor Rozin’s altar-server who, twenty days after the death of his spiritual father, replaced him at his post (there is no other way of putting it) as rector of St. George’s Church. He shows me a video: an interview with Fr. Igor (Rozin) for local television.

Standing in front of the modest iconostas in his little church, where a week after this was recorded he would accept his martyr’s death, Fr. Igor tells of the distant Christian past of his region.

“According to historical records, the local inhabitants—the Balkars—were Christians before their forced conversion to Islam.” Unaccustomed to giving interviews, he staidly pronounces each word somewhat like a child.

He then remembers the most important thing and lights up: “Here, by the way— somewhere in this place where the church is now—was a church dedicated to St. Theodore. We have two Saint Theodores: the Stratelates and the Tyro. I don’t know to which Theodore that church was dedicated, but it’s indeed the case that there’s good historical evidence that there was an Orthodox church of Byzantine construction here. The old people—the very old people—remember its ruins from before the city was built. The location of the Christian church was passed on from generation to generation.”

When and who built and consecrated a church in honor of the Great-Martyr Theodore on this land is not known and not overly important. The most important thing here is something else: signs of Divine Providence. Above Tyrnyauz towers Mount Totur, whose name is a distortion of the Greek name “Theodore.” Christ, as it were, left us a note, right on top of the peak of Totur, terrible and joyful to read. On the screen is a soldier of Christ from the last times, witnessing to his loyalty and love for Christ by his blood, shed at the foot of this mountain at the dawn of the third millennium.

It is strange to catch his gaze now, as he occasionally looks at the camera: still a simple person in whom, however, one can make out much more than in the usual human gaze.

It is rather gloomy in the tiny church: either the old Betacam film is distorting the color or else the day really was outstandingly dreary. But behind the walls an invisible spring is gathering in the lungs: the house’s windows are open and breathing, a ball is somewhere evenly striking the asphalt, and life seems as comfortable and cozy as the clothes one wears at home, which have long since taken on the body’s shape. Many parishioners now remember that in the sermons of his final months he spoke constantly about death and the Heavenly Kingdom. “I was still unchurched and rarely went to services. I didn’t understand it. I thought that the Heavenly Kingdom is somewhere far away and I have no plans to die… I have children and a husband here… There are material deficiencies that need to be addressed… But now the time’s come that I do think about the Heavenly Kingdom.” This is Valentina, one of God’s people, whom the Lord found fit to be in church when Fr. Igor was murdered.

+++

He knew what would happen to him at least a week ahead of time. The person who killed him on the feast day of St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), Bishop of the Caucasus—whose sermon on death Fr. Igor cited in nearly every one of his final sermons—first visited the church on May 6. It was the parish feast day of St. George the Trophy-Bearer. Fr. Igor did not speak with the visitor in the overflowing church, asking him to come back in a week. Did he know that this man would kill him? Of course he knew, and he was exceedingly sorrowful, even unto death [Matthew 26:38]. He lit up after serving the Liturgy, after receiving Holy Communion. The service came to an end. Firmly sending home his altar-server who normally accompanied him on pastoral visits and, having dismissed everyone, Fr. Igor went to take Holy Communion to a sick parishioner.

Valentina tells the story of how it all happened. “I remained alone and began to clean up the church. I was about to get ready to leave when a young man appeared at the door and asked for the priest. I said that Batiushka had left, and asked where he was from. He replied that he was from Nalchik and wanted to attend the service. Balkars frequently visited us to speak with Batiushka, so this didn’t surprise me.”

Fr. Igor soon returned. He went into the altar to place the tabernacle containing the Holy Gifts on the Holy Table. When he exited, his killer met him on the threshold of the altar. Valentina heard how Fr. Igor led him into the sacristy—a room adjacent to the altar—and how he said: “have a seat.” A short time passed, and then there was a noise. She lifted her head and saw, in the open door, how Fr. Igor fell down and the other man stood over him with a knife. Just like the New Martyrs of Optina—Vasily, Fr. Trophim, and Fr. Ferapont—as well as like St. Seraphim of Sarov, Fr. Igor was a man of great physical strength; he was, no joke, a rescuer and master mountain climber who scaled the highest peaks and lifted people out of crevices, but he did not resist. This was conscious suffering for Christ: this person had come to kill Fr. Igor for being a priest.

“This was incomprehensible. This was impossible. I screamed ‘Batiushka!’ and ran to him through the church. I began to open the door. This man bent down over Batiushka and I couldn’t understand that he’d come to kill him. I pushed him toward the door and said: ‘What do you need from Batiushka? Leave Batiushka alone! Leave!’ He again bent down, I again pushed him toward the door, and he turned toward me with the knife, but I had nothing in my hands and so had no way of helping Batiushka. It seems that he struck him twice with a knife in my presence. I began to scream terribly. He stepped over Batiushka, who was lying down with his right hand lifted: he wanted to cross himself, and he did not resist. I heard how he said: ‘Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commit my soul.’”

She remembers the rest vaguely: how the killer ran away (“He ran like a demon,” says Valentina, and for some reason I know just what she means) and how she called someone. She called Andrei the altar-server. When Andrei came running, Fr. Igor’s soul had only just departed.

Today this former altar-server, who carries out his ministry here as before, again remembers this day. When Hieromonk Igor talks about this, his voice becomes very quiet.

“There was, of course, the smell. I’ll probably never forget the smell of his blood. The blood of a martyr. There was a special smell… For some reason a lot of blood was shed… The floors are uneven… We had a font – we still have it, it’s just in a different place – and almost all the blood flowed under the baptismal font.”

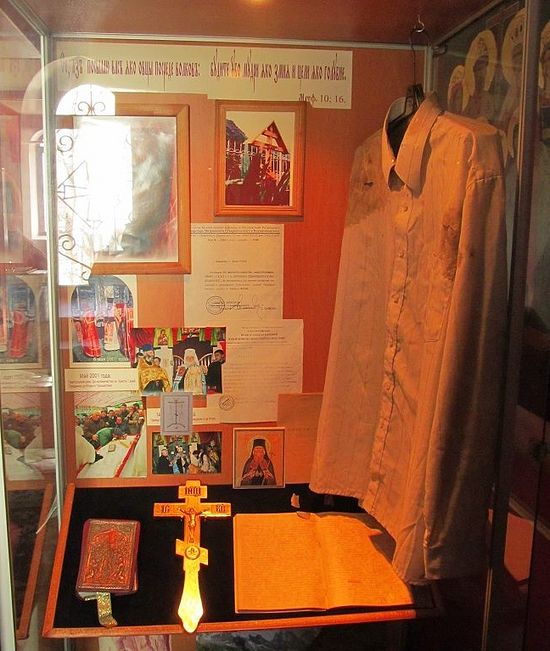

The place where the baptismal font stood. Behind the glass in the blood-stained shirt the Fr. Igor wore when he was killed.

The place where the baptismal font stood. Behind the glass in the blood-stained shirt the Fr. Igor wore when he was killed. Then, twelve years ago, Metropolitan Gideon (Dokukin) of Stavropol and Vladikavkaz blessed the altar-server Andrei to be tonsured to monasticism and ordained to the priesthood in order to replace Fr. Igor Rozin in the place of his ministry. Andrei was tonsured in honor of the Holy Right-Believing Prince Igor of Chernigov. “They killed one Fr. Igor—so here is another Fr. Igor for you” Vladyka said then.

Twelve years have since passed. The community decided not to leave the place where the blood of the new witness to Truth had been shed. The ramshackle church was rebuilt. Today, by God’s mercy, this small flock still lives and carries out its ministry here.

We are sitting in the same apartment in which Fr. Igor Rozin lived during the last months of his earthly life. We are watching an archival video on which the former dean of churches in Kabardino-Balkaria, Fr. Leonid Akhidov—now Archimandrite Lev—is giving a sermon in the Church of St. George the Trophy-Bearer:

“Christ is Risen! In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit! Seven years have passed since Fr. Igor’s tragic death. This is a church-on-the-blood. There is a great deal of red here. The Lord said: they drove Me away, and they will persecute you. It is said that, at the Mystical Supper, Satan entered Judas. Who killed Fr. Igor? Satan himself. He is the adversary: the adversary of Christ and the adversary of faith. He is the adversary of truth.” Fr. Lev keeps silent for a long time, looking somewhere off to the side. When he turns back around, one can see that he is weeping. “But the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church. Here, on an empty place, Fr. Igor began his ministry. He was successful, for which reason the envier of the human race could not stand it and decided to eliminate him, so that Christian singing and the preaching of the Gospel would die down here… A beautiful church has been erected on this place. I repeat Tertullian’s maxim: ‘The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christianity.’”

memory eternal!