SOURCE: Assyrian International News Agency

By Jane Burgess

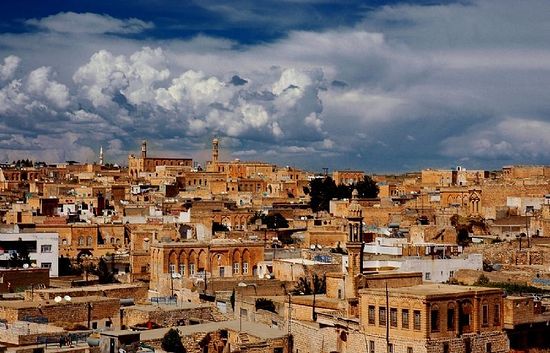

Miydat's Assyrian Orthodox community is still encumbered with festive cookies and candied nuts from their Christmas festivities. In every home, tables groan with remnants from the recent celebrations, which for many of Midyat's residents found themselves in situations far safer than the previous holiday spent in Syria.

Often reported to be sympathetic to the regime of Syrian president Bashar Al-Assad, although all the Christians in Midyat are quick to assert their neutrality, Syria's Christian and Assyrian communities have come under an increased threat from more extreme Sunni rebel groups, like Jabhat Al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS); and many have sought refuge across the border in Turkey's south-eastern provinces.

"The Islamists were kidnapping us. It's another kind of terrorism," said Kalill, a former resident of Al-Qamishli, now living as a refugee in Midyat with the help of the local Assyrian community. A journalist by trade, Kalill had been critical of the Jihadists in the north of Syria near his home. "I didn't know which day the Islamist groups would come into my home. I had been writing against them, so I was threatened," he told The Media Line.

Turkey is home to nearly 600,000 registered Syrian refugees with hundreds of thousands more living in the country without registering with the authorities. The presence of refugees from minority groups within Turkey is a 'see it to believe it' phenomenon, with most Turks and Syrian's refusing to believe they exist. Abuna Ishok Ergun, a Syriac-Orthodox priest in Midyat, says many of the Christians who end up in Midyat do so because, "In Istanbul they won't accept them as refugees because they say there is no problem."

But the refugee population of Turkey is not a homogenous group. While the country geographically and politically lends itself to the arrival of large numbers of mainly Sunni Muslim refugees from Syria's north, amongst them live Kurds, Alawites and Christians.

Each group is assisted by their closest Turkish relatives, be that literal -- as is the case with many of the Kurdish refugees who arrive in the country and stay with family; or figurative -- like the Alevi mosques in Istanbul who aid their Alawite neighbours.

The Assyrian community in Midyat, close-knit and supportive, is initially suspicious of a stranger but they soon open up and welcome the chance to tell their stories.

Sahaleb Mouza, who left Syria seven months ago, says he likes Midyat and has been welcomed by the local Assyrian networks, but he misses home. "It's not like Syria. It's not like my own country," Saheleb told The Media Line. He said he took his children and left because, "We were in Qamishli; there's no electricity for eight hours a day and no schools for the children. There is no future."

The Raber family now shares a small apartment in Midyat. Their boys, aged 22, 20 and 19, fled Al-Hasakah with their mother after their father was killed by Jihadist groups who later attempted to kill one of the brothers. They receive help "sometimes from the church and sometimes from family." Eziky, the eldest son, said, "We are safer here but we don't have the best life. We were studying before and now we don't do anything."

Around 1 million Assyrians were living in Syria before the conflict. They form a sub-section of the Christian community (although there is very small minority of Muslim Assyrians) of Syria, who number around 2.5 million or 10% of the population.

The Assyrian Christians live mainly across the north east of the country, around Qamishli and Al-Hasakah, towns just over the border from Turkey which are now controlled by the Kurdish military in a place commonly referred to as 'Rojova'. Pockets of Christians also lived in Mal'oula and Saidnaya as well as in the larger cities of Aleppo, Latakia, Damascus and Homs.

In Mal'oula, 11 Christian nuns were kidnapped in early December when the city was overrun by rebel forces. Despite the outcry from the international community and parties within Syria, the nuns remain missing. The incident is cited by all the families in Midyat as evidence of the rising sectarian violence in Syria.

"Every ethnic group has lost everything. It's Sunni vs Shia; all the other ethnic groups have been affected," said Kalill. "In Qamishli, before the crisis, we were living with our neighbors with no problem."

For now, the Kurdish military wing called the People's Protection Units (YPG), which is the predominant fighting force in the Rojova area in Syria's north east, works alongside the Christian and Assyrian communities and protects them. Their common enemy, the Jihadist rebel groups of Jabhat Al-Nusra and others, create a reason for their marriage of convenience. But the Christian community is not wholly convinced its interests will be protected by the Kurds who seek autonomy and their own state. "We are worried about President Barzani, that he won't respect our rights," Kalill says about the President of Kurdish Iraq who is seeking a united Kurdistan: "I expect in the Rojova area it will be a sectarian war in the countryside."

Father Abuna Ishok Ergun, explains that there were around 130 Assyrian Orthodox living in Midyat before the crisis. Over the last twenty months another 300 individuals have arrived and are cared for in 13 villages in the area. Twenty more had arrived just two days before. The war has been hard on them, according to Father Ergun. "They have different problems like insomnia and depression."

The response of the church is thorough. Father Ergun says they discussed the likely influx of refugees back in 2012 with the local Archbishop and made a home for the Assyrian Orthodox in a local monastery when they began coming in numbers later that year.

A Turkish refugee camp was built in the region and was to have a sector for the Christian community. After much controversy about whether it was the correct response for the refugees in question, just three Christian families moved into the camp, with the rest choosing to stay within the Midyat community and in the surrounding villages. Many of the families move onto Europe or elsewhere, using the region as staging post.

The act of leaving Syria is, in many cases, sudden and unplanned, Father Ergun told The Media Line. "The Jihadists enter their homes and say you can't take the money or your phone, and if they argue they kill them. They leave so they will not be killed, so they won't kidnap their children and destroy their shops and houses."

Part of the problem, according to Father Ergun, is that, "The Christians in Syria don't have an organization that is defending them." This is a sentiment echoed by all the refugees in Midyat. Their sense of being in it alone is palpable; they feel Syria has now become sectarian with other groups supported by external governments and organizations. Even the Kurds have a strong political and military presence both in Syria and in Turkey.

Once they flee Syria to predominantly Sunni Muslim Turkey, the situation again leaves them with little support outside of the church. Yet, despite the difficulties they face in Turkey, Sahaleb Mouza says they would rather be here than elsewhere. "It's better than Lebanon or Jordan. It's bad for Assyrians in Lebanon."