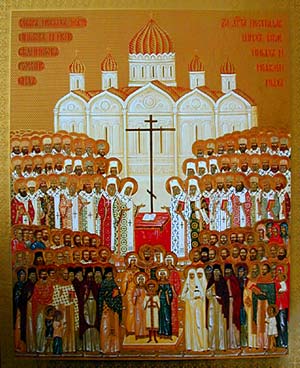

Icon of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

Icon of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

The key event in the history of the Church in the 20th century that marked the end of "Synodal era", which lasted since Peter I, was the National council of the Russian Orthodox Church that opened on August 28, 1917 and lasted off and on till September 7, 1918. It reestablished the Patriarchate and the ancient tradition of regular Councils as the supreme bodies of ecclesiastical authority. The authority of Patriarch Tikhon (Bellavin), formerly Metropolitan of Moscow, elected by the Council on November 18, 1917, would strengthen Church unity and help preserve the rich Russian moral and cultural heritage for future ages.

Patriarch Tikhon started his road to Calvary in the Kremlin Dormition Cathedral. At that time the central drum of the cathedral’s five domes gaped with a shapeless breach—it was a bad sign, but the Patriarch did not change the ancient place of enthronement.

He walked firmly along the Kremlin yard, and the believers looked at the long awaited protector of the Church with great hope. They thought that during the time of troubles the Patriarch’s authority would strengthen Church unity and infuse a fresh spiritual impetus into the religious life of Russia. Few believed in the revolution's "democratic" foundations, so loudly proclaimed by its heralds amidst the whine of bullets.

Reasoning from the principle of ideological monopoly, the Soviet authorities regarded Patriarch Tikhon’s election as a threat from the opposing political force, because he would be the successor and carrier of the ideas of abolished monarchy. Fear of the union of the real contemporary political opponents under the Church banners compelled the Bolsheviks to start a war against the Church, for which they needed a weighty and obvious pretext.

Atheist propaganda began counting the "anti-government" deeds of the clergy from November 11, 1917, when in the letter of the National council the socialist revolution was called an "invasion of antichrist and raging godlessness". However, nobody ever wrote about the actual reasons for adopting such an appeal. It was preceded by closing all educational institutions of the Russian Orthodox Church, by decree of the People’s Commissars Council (SNK).

The next day, a "Declaration of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church" appeared on the streets, squares and churches of Moscow:

"On Sunday, November 12, in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, after the Liturgy the memorial service (panikhida) will be held on behalf of the Holy Synod for all who have fallen during the civil bloodshed on the streets of Moscow. The Moscow residents—the rich and the poor, the noble and the common, the military and the civil—all are invited to come, forgetting dissension among parties and keeping in mind only the commandments of Christ’s great love to unite in the common prayer for the blessed repose of the deceased".

The panikhida for those killed, irrespective of their political color—"red" or "white"—took place. Not only the members of Moscow Council tried to prevent the civil disorders, the parish clergymen also did as much as they could. Ioann Kochurov, the archpriest of the St. Catherine Cathedral in Tsarskoye Selo village near St.-Petersburg, was one of those men. On November 12, 1917, he headed a religious procession with prayers for the cessation of fighting. His sermon during the procession summoned the Orthodox to composure in view of the coming ordeals. On November 13, 1917, the Bolsheviks occupied Tsarskoye Selo. Arrests of the priests followed, including Fr. Ioann. The furious soldiers took him to the airfield where he was shot without any legal proceedings or investigation, in presence of his son, then a grammar-school boy. Only in the evening could the parishioners take the body of the murdered pastor to the chapel of the palace hospital and from there—to the St.Catherine Cathedral, where on Saturday, November 17, 1917, the Memorial was served. At the request of the parishioners Fr.Ioann was buried under the Cathedral. Priest-martyr Ioann was canonized by the Assembly of Hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church on December 2, 1994.

On December 31, 1917, the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VCIK) and SNK on civil marriage, children, and keeping the civil registry books, declared church marriage invalid. In January 1918 the SNK decree abolished all army priests, cancelled all state grants and subventions to the Church and the clergy.

On January 20, 1918, the SNK decree on liberty of conscience, church and religious societies was adopted (published on January 23), which separated the Church from the State, started nationalization of the church property and placed the Russian Orthodox Church within the narrow limits of numerous bans and restrictions. From that time on, it was longer a legal entitiy; it lost its property and the right to acquire property. The draft of this decree, published on January 13, 1918, provoked a storm of indignation among the clergy and believers.

On January 25, 1918, the National Council evaluated the Bolshevik decree as follows: "under the image of the law on liberty of conscience, it represents an evil encroachment upon the entire order of the Orthodox Church life and an undisguised act of its persecution".

In the evening of the same day, Russia was shocked by the terrible news: in Kiev, Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev, the oldest hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, was killed. His martyric death was the first among the hierarchs (on April 4, 1992, Metropolitan Vladimir was canonized by the Assembly of Hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church).

On January 25, 1918, late at night the news about the Kiev tragedy reached Moscow. The participants of the Council took the most important decisions about the further existence of the Church under the Bolshevik persecution: the Patriarch was suggested to choose several locum tenens in case of his illness, death, or other sad possibilities. The candidates had to be named in the order of precedence.

Three locum tenens were named: Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov), Metropolitan Agafangel (Preobrazhensky) and Metropolitan Peter (Poliansky).

It was also decided to introduce during the services a special petition for the persecuted for the Orthodox faith and Church, deceased confessors and martyrs, and to set an annual memorial on January 25 or the evening of Sunday following it: the Memorial day of new martyrs and confessors.

The first wave of repressions (1918-20) took about 9,000 lives. The Russian Church entered the path to Calvary.

Repressions against the clergy did not lessen even after the Patriarch’s letter, "On the cessation of clergy’s fight against the Bolsheviks" in September 1919. It was carried out unilaterally: the priests did their duty at the places of their ministry and rejected everything that was contrary to the Patriarch’s letter, but the Soviets proceeded with their policy of terror.

They year of the great famine in Russia is memorable for one more tragedy—the state campaign for requisitioning the Church valuables. For a long time the official version dominated, according to which the Church resisted to hand over its valuables whichg the authorities intended to use for rendering help to the starving people. In reality, everything was quite different. As early as in August 1921, Patriarch Tikhon established the church committee to help the starving. On February 19, 1922 the parishes and church boards obtained the Patriarch’s permission to donate precious church decorations and other things, which had no liturgical use, for the needs of the starving. An Orthodox movement of rendering help to the starving that was gaining momentum was not desired by the authorities. Requisitioning of church valuables according to Lenin’s plan had to make a fund of "several hundred millions rubles". This was the financial aspect of the campaign. But there was also a political one. In the course of requisitioning it was decided to start "the most resolute and merciless combat against reactionary clergy and suppress its resistance with such violence that they would not forget it for several following decades". In Moscow, Petrograd, Shuya, Ivanovo-Voznesensk, Smolensk, and Staraya Russa, processes took place followed by mass execution of the clergy and other participants of the resistance against the requisition of valuables.

In Petrograd there were 80 accused and 4 death sentences, including Metropolitan Veniamin (Kazansky); in Moscow—154 accused, 11 death sentences. Even the Patriarch was arrested. At that very hard time for the Church, the State did its utmost to stimulate the activity of a renovation movement formed already before October 1917: it backed renovation editions; the OGPU (Unified State Political Directorate) deported disagreeable bishops; divided the laity. This policy was aimed at breaking up the Orthodox Church into groups hostile to each other. Thus it would cease to be a force spiritually opposing the Bolshevik dictatorship. The number of martyrs grew. During the period of the campaign of requisition of the church valuables, over 10,000 people were condemned, and 2,000 shot.

During the hardest years of totalitarianism that quickly gained strength, Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky) was one of the most significant figures of the Russian Orthodox Church, who made his personal sacrifice for the salvation of the Church life. Appreciating the viewpoint of the Metropolitan N.Berdiaev wrote from abroad: "Heroic intransigency of a single person, ready to go to execution, is impressive, weighty and admirable. But there, in Russia, there is also another heroism, another sacrifice, that is not easily appreciated by people. Patriarch Tikhon, Metropolitan Sergius are not individual persons, who can think only about themselves. Not only their own fate is in their hands, but also the fate of the Church and church people as a whole. They can and must forget about themselves, about their purity and beauty and speak only what is salutary for the Church. It is an enormous personal sacrifice. Patriarch Tikhon made this sacrifice, so did Metropolitan Sergius. Once this sacrifice was made by St.Aleksandr Nevsky in his trip to the Khan Horde.

"An individual person can prefer personal martyrdom. But the position of a hierarch at the head of the Church is different, he has to choose a different martyrdom and make a different sacrifice."

In 1930, over 30 bishops rejected administrative submission to the Primate of the Russian Church Metropolitan Sergius, disputing the compromise with the authorities and not seeing any real external circumstances of Church life. In the history of the Church all the schisms resulted in its weakening. The majority of the Nepominately (those who refused to pray for the authorities) were arrested and sent to labor camps and in exile in 1928-1929: Metropolitan Joseph (Petrovykh), Archbishop Seraphim (Samoilovich), Archbishop Varlam (Ryashentsev), Bishop Viktor (Ostrovidov), Bishop Dimitry (Lyubimov), and many other who chose the way of martyrdom.

The offensive against the Russian Orthodox Church was continued with strengthening of the campaign of the militant atheists, and quick industrialization of the country gave a stimulus to the "anti-bell" campaign.

Metropolitan Sergius found himself in isolation, face to face with an atheist orgy, that took larger and larger scale. After taking the bells the churches were demolished. From 1930 to 1934, their number reduced by 30%.

Stalin’s thesis about intensification of class struggle on the way to socialism untied the hands of not only the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs), but also of the atheists. Thousands of pastors and believers were repressed. Each of them had to fill a questionnaire, that determined his "grade" of the regime’s tolerance for him. Parish life was controlled by supervision inspectors who were stool-pigeons of the NKVD.

In summer 1937, by Stalin’s command, an order was given to shoot all the confessors who were in prison or in camps within four months. Priest-martyr Metropolitan Peter (Poliansky), who had spent 12 years in prison and exile, was killed. The sentence was executed on October 10, 1937.

One by one the hierarchs were killed, crowing their deeds as Confessor-Martyrs by shedding their blood for Christ. On December 11, 1937, on the training ground of Butovo near Moscow, Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov) was shot. On the last day of the horrible year 1937, one of the most notable confessors of Orthodoxy Archbishop Faddey (Uspensky) was shot. The year of the "Great Purge" and the following year 1938 were the hardest for the clergy and laymen—200,000 repressed and 100,000 executed. Every second priest was shot.

But the Orthodox Church put up a strong resistance to the totalitarian regime. Clergy and laymen ended their earthly way with great faith, firmness and self-denial. And if it comes to glorifying all Russian martyrs of the 20th century, the Russian Orthodox Church will become the Church of the Russian New Martyrs.

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia glorified the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia in 1981. Immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Church under the leadership of Patriarch Alexei II began glorifying some of the New Martyr's, beginning with the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev, and Metropolitan Benjamin of Petrograd in 1992. In 2000, the All-Russian Council glorified Tsar Nicholas II and his family, as well as many other New Martyrs. More names continue to be added to list of New Martyrs, after the Synodal Canonization Commission completes its investigation of each case. The Russian Church celebrates the feast of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia on the Sunday nearest January 25th (o.s.) / February 7th (n.s.)—the date Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev's martyrdom (the first Hieromartyr of the Bolshevik Yoke) (from Orthodox Wiki, http://orthodoxwiki.org/New_Martyrs_and_Confessors_of_Russia).

I have a list of over a thousand in Russian, but it is an obvious fact that thousands of Orthodox in the West

are unable to read cyrilic script.WE who are converts love the New Martyrs too, and wish we could learn about more of them.