Source: Trib Total Media

Christian refugees from Mosul have taken refuge in Saint Matthew monastery near Al-Faf, Iraq on Wednesday, June 18, 2014.

Christian refugees from Mosul have taken refuge in Saint Matthew monastery near Al-Faf, Iraq on Wednesday, June 18, 2014. Perched on a rocky, sand-colored mountain dotted with green shrubs and ancient caves, the Monastery of St. Matthew was a sanctuary for some of the earliest Christians.

With the fall of nearby Mosul to Islamic extremists, its thick 4th-century walls again are a refuge.

Christian families, who fled Iraq's second largest city, fill courtyard rooms normally used by monks and pilgrims. Children play on the steps while women help a male cook in the monastery's kitchen; others hang washed clothes in the scorching heat as a church bell peals.

Men sit in the shade, drinking tea and smoking cigarettes, worrying about their families.

Everyone follows the news, trying to learn what their fate may be.

“All the time I have stayed in Mosul — despite the persecution of the Christians in 2007 and 2008, I didn't leave,” said Father Yousif al Banna, a Syrian Orthodox priest.

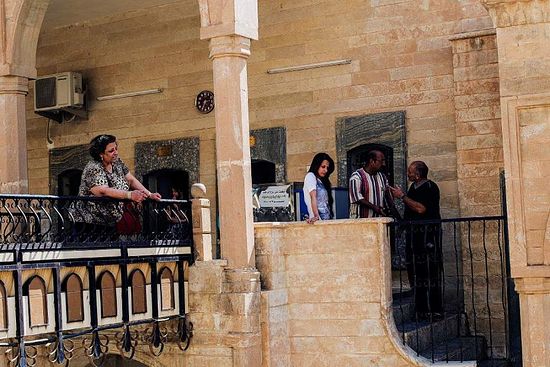

Father Yousif Al Banna talking with other Christian refugees in Saint Matthew monastery near Al Faf, Iraq on Wednesday, June 18, 2014. Father Yousif said “I fear our churches will be burned and possibly no Christians will return.”

Father Yousif Al Banna talking with other Christian refugees in Saint Matthew monastery near Al Faf, Iraq on Wednesday, June 18, 2014. Father Yousif said “I fear our churches will be burned and possibly no Christians will return.” “When all the Christians and Muslims in Mosul heard that ISIS was coming, they knew from Syria that they take the heart out of their enemy and eat it, and so they left in one night.”

ISIS, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, used such brutal tactics to fight Syria's regime that al-Qaida and other Islamist groups disowned it.

Many people fear its conquest of northern Iraq, backed by Sunni Muslims, will explode into a full-blown sectarian war with Shiites, inflaming other Arab states.

Iraqi Christians — many of whom still speak Aramaic, the language of Christ — are caught in between, which could decimate their dwindling numbers.

The Syrian Orthodox Church is Iraq's second-largest Eastern Christian sect, after the Chaldeans. Al Banna estimates 1,750 Syrian Orthodox families lived in Mosul before the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq; afterward, Islamist attacks that killed priests and followers reduced that to just 400.

“Now, possibly nobody will return, maybe just 100 families,” he said. “We believe what is happening is because of the American and British invasion. This Sunni-Shia division was created by the West for (its) own political aim.

“Now, if you are Christian, you are killed. Your daughter can't walk in the streets, she has to dress like an Islamic fundamentalist. ... Our churches will be burned.”

Miriam, a Syrian Orthodox Christian who feared to give her last name, said her escape route from Mosul was a bridge blocked by the Iraqi army.

“But then I saw the army fleeing and removing their uniforms,” so she ran. Days later, she gathered a few belongings, put on a headscarf to blend in with Muslim women, and walked out.

She saw ISIS's black holy-war flags along the way: “One said, ‘The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria welcomes you.' ”

She didn't fear the masked Sunni fighters she encountered because “they are Iraqis like us. I was only afraid of ISIS, the guys who wear their pants to their calves and have long beards. They say they won't hurt us, but we've seen what they've done in Syria, when they killed Christians.”

Abu Marwan al Aswad said his Muslim friends phoned, telling him to “leave now, because that extremist Islamic group is coming here.”

“I walked out the door at 2 a.m., and I saw my Muslim neighbors leaving. How could I stay?”

Fifty families fled to the monastery, others to cities in Kurdish-controlled Iraq; 25 families remain here, according to church deacon Imad al Banna, 26.

“ISIS came to our church and asked, ‘Why did the Christians leave? We have no problem with the Christians, and we won't hurt them. We only bring freedom from the Iraqi army,' ” he said.

“The government did nothing, and we don't know what our future will be.”

His 18-mile drive to the monastery took eight hours because a half-million panicked refugees clogged the road.

He, too, laments the dwindling Christian numbers: “No one is thinking of staying in Mosul.”

This monastery, founded in 363 A.D. and one of the oldest in the Middle East, is known for its large number of ancient manuscripts and a holy relic — a piece of bone from the Apostle Thomas.

Al Banna sent people back to St. Thomas Church in Mosul to gather other relics and manuscripts, so they wouldn't be destroyed.

Journalist Khazwan Elias fled to Erbil when ISIS captured the city. “We know 100 percent that ISIS will try and make us pay the jizya,” a tax that Islamic leaders once levied on non-Muslims.

“My life is already over,” he said, with both arms held palms-up and tears in his eyes. “I am worried about the future of my children. ... We don't know what will happen.”

ISIS seized the television station where he worked and three others; he is struggling to pay the much-costlier rent in Kurdistan but found work at a local Christian station. “We are all working to put food on the table; we just want food and peace,” he said.

“Every 30 or 40 years, something bad happens here, and the number of Christians decreases. The future of Christians in Iraq is dark.”