July 18, 2015

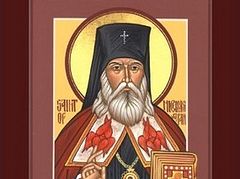

St. Nicholas of Japan

St. Nicholas of Japan As astonishing as its vigor is the fact that Russia’s eastward expansion, beginning in the 16th century, went all but unnoticed, by Japan no less than by Europe.

Japan and Russia were bound to meet. Russian sailors reached the Sea of Okhotsk in 1639. By 1715, Russian traders were in the Kurile Islands and in Sakhalin, on Japan’s very doorstep. Japan at the time was shuttered against the outside world—no one allowed in, no one allowed out; official policy since 1638. Japan’s rulers knew two damning facts about Europeans: they were Christians and they were colonizers. Thus sakoku, the defensive “closed country” policy.

There was intermittent contact nonetheless. Russian and Japanese traders and trappers mingled in the northern islands. At intervals a Russian ship would approach Japan, seeking trade. The Japanese replied that their law did not permit dealing with foreigners except under very tight restrictions at Nagasaki. The Russians could try their luck there if they liked; otherwise they’d better make themselves scarce. Russia did not press the point. It hardly seemed worthwhile.

In 1811, Capt. Vasily Golovnin, in command of a Russian warship exploring the Pacific, landed at Kunashir in the Kuriles and was taken captive, along with some of his men, by a Japanese armed force. Later he wrote a book about his two years’ imprisonment in Hakodate, Hokkaido. Treatment was humane, but “we were inconsolable when we recollected the last words of (the magistrate). He desired us to regard the Japanese as our brothers and countrymen, and mentioned not a word about (our returning to) Russia. … But we had firmly resolved that such should not be our fate …; we would attempt either to liberate ourselves by force from the power of the Japanese, or to escape secretly during the night.”

The escape was foiled, but it seemed best not to provoke Russia further. The prisoners were released in August 1813, Golovnin little dreaming of the decisive impact his book, still unwritten, would have on a countryman yet unborn. The name by which that unborn countryman came to be known is suggestive: St. Nikolai Yaponskii.

Among 19th-century Russians whose thoughts turned occasionally to Japan was the novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-81). In “The Idiot” (1868), he portrays a tragic heroine whose seduction as a child has left her traumatized and self-destructive. A gentleman in her circle professes to see something “Japanese” in her transports: “Do you know … they say something of the sort is done among the Japanese. They say anyone who has received an insult goes to his enemy and says, ‘You have wronged me, and in revenge I’ve come to cut open my stomach before you,’ and with those words actually does rip open his stomach before his enemy, and probably feels great satisfaction in doing so … There are strange people in the world!’”

Years later, in 1880, Dostoevsky read newspaper accounts of a Russian priest who was devoting his life to propagating the Russian Orthodox faith in Japan. The priest was briefly back in Russia. Dostoevsky, deeply religious and therefore deeply interested, paid him a visit. The two men found much to talk about, mainly their shared faith in the Christian regeneration of fallen mankind under Russian leadership. Dostoevsky, a journalist as well as a novelist, planned an article—never written due to his sudden death months later—on Nikolai Yaponskii and his missionary work among the Japanese.

Born in a village near Smolensk in 1836, Ivan Kasatkin, the future St. Nikolai, dreamed as a young seminarian of spreading the Gospels in China. It was Golovnin’s “Memoirs of a Captive in Japan” that showed him his true destiny. Japan, not China, would yield him his harvest of souls.

In August 1860, the 24-year-old monk trekked across Siberia, wintering in the Russian Far East and arriving in Hakodate the following July. His first impressions, recorded in a letter, were discouraging:

“When I was on my journey I dreamed much of Japan. It appeared in my imagination as a bride awaiting my arrival with a bouquet. I expected that soon the good news of Christ would spread into its darkness and everything would be renewed. Having arrived here, I saw that my bride was enjoying the most prosaic sleep and was thinking nothing of me”—or of the good news of Christ. Sakoku had ended by then, breached by the American Navy in the 1850s, but Christianity remained under a cloud. “The Japanese of the time,” Nikolai wrote later, “looked upon foreigners as beasts, and on Christianity as a villainous sect, to which only villains and sorcerers could belong.”

He was, evidently, a determined character. “When I arrived in Japan,” he wrote, “I summoned up my strength and began to study the local language. Much time and effort were lost while I was getting acquainted with this barbaric language.”

He mastered it, however, and translated much of the New Testament into Japanese. By 1912, the year of his death, the Japan’s Orthodox community under his care numbered some 33,000. His own mind opened as he opened the minds of the Japanese. Might all religions, each after its own fashion, be striving for the same goal? Of Buddhism, Nikolai wrote, “The teachings of the fullness of Buddha’s love … irresistibly amaze us. It is possible that, listening in a Buddhist temple to some sermon, you will forget yourself and imagine you were listening to a Christian preacher.”

Push came to shove. Flexing new imperial muscle, Japan and Russia went to war in 1904. It was a savage, feral dogfight, casualties on both sides numbering hundreds of thousands. Father Nikolai was torn. Japan had become his second homeland. Which side merited his prayers? Both, and yet — “the Japanese Church must not be left without a bishop, and therefore,” he wrote home, “I am staying.”

Russia’s defeat, hindsight shows, was a nail in Tsar Nicholas II’s coffin, but in 1905, his thoughts on higher spheres, he wrote Nikolai, “You have shown to all of us how the Orthodox Church of Christ is alien to all worldly dominion and every tribal animosity, that She equally embraces with love all tribes and peoples.”

Yaponskii was canonized in 1970.