“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Henry David Thoreau, Walden

These famous words by Henry David Thoreau rebounded in my mind within the woody hills of Wayne, West Virginia. It takes 11 ½ hours by car without stops from NYC to get to this secluded spot. The road trip to get there is endless; one Interstate highway weaves ribbons of incessant road only to lead to another and yet another. The hum of the traffic turns your brain into mush; the kerkunk of the seams in the freeway lulls you into a mesmerizing half-alert, half-comatose state. A minute driving at 70 miles per hour is a petite eternity. It is almost as excruciatingly long as watching for a minute to pass on the treadmill. The huge swath of empty space that makes up this land of the freeway of ours seems to repeat itself, the same stretch of highway exists on the I-81 near Chambersburg, and the I78 near Harrisburg and the I64 near Frostburg. Places like Left Hand, and Mt Carmel, and repeating towns like Charleston (West Virginia or South Carolina or Massachusettes?) whizz past your fuzzy mind. Thank God Almighty for Google Maps or else I would not have been able to get there.

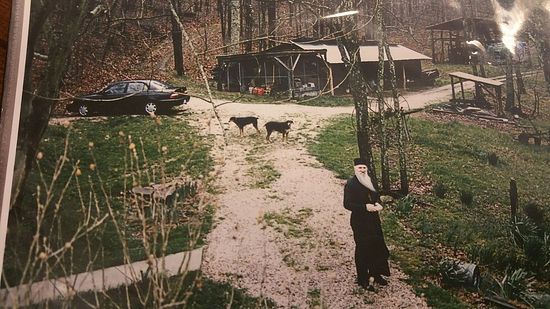

I had come to the Hermitage of the Holy Cross monastery nestled in the back woods of a nondescript town in one of the poorest parts of the country. Run-down trailers put together with chicken wire, a hodge podge of rusty signs, muddy puddles, plastic kiddie trucks and mangy dogs in the front yard, yelled “We poor, y’all.” The last 28 miles were the longest (isn’t that always the case? The last stretch is the hardest.) The GPS read 28 miles approximately 38 minutes. Huh? I had zipped through 28 miles in 20 minutes on the Interstate. How could this be possible?

I stopped into a repair shop to have a local man named Meredith, a short, tense-eyed fellar left cheek smudged with grease, who looked like he could have come right out of The Dukes of Hazzard, explain that the speed limit drops from 35 to 25 going on the Left Fork Miller’s Fork Road. His directions were spot on at least because at that point the GPS had difficulty picking up a signal. “Go on Rte 17, turn left at the “Y” in the road, keep going till you come by the restaurant then the saw mill, then follow Miller’s Fork Road to the Left Fork Miller’s Fork Road.”

That forked road sinuously wrapped around the hills in a dizzying daredevil backhanded way. That last stretch of dirt country road did me in: round and round the hills past the wilderness refuge managed by the US Corp of Engineers, full of blind hairpin curves without protective barriers that plummeted to 50 foot drops while pick up trucks raced at 40 mph the other direction.

There’s a reason why monasteries and other places of spiritual pilgrimage require so much physical effort to get to them. The journey to get there does something to you. It is both torturingly boring and stressful at the same time. The physical fact of getting through such a long road puts you in a contemplative stance. It forces you to decompress and focus on the road itself. After all, there is only so much you can do behind the wheel; you have enough mind space to think of this and that, but your wits must always come back to the ROAD. At the same time, the journey is treacherous. Whether by foot, by vessel or by vehicle, the journey is fraught with danger. After your 11-year-old car starts jumping back and stalling five or six times out of the blue without warning lights on the dashboard, when you are passing through miles and miles of road going through the grey Appalachians without a service station in sight, when your 7-year-old in the back seat is having a meltdown because the DVD player in the computer has stopped playing Bugs Bunny and his pals, that’s when you start praying “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me” over and over and over and over. You realize while on the journey, especially if it’s a pilgrimage, that it depends on God whether you make it to your destination or not. Every journey, begins and ends with God.

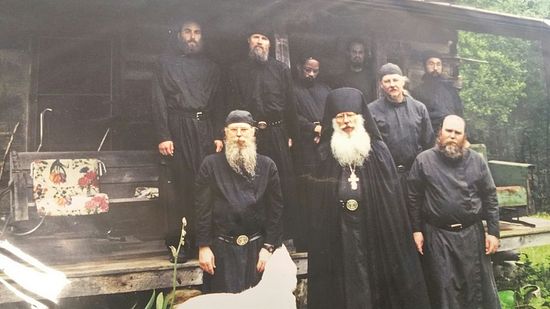

The Hermitage of the Holy Cross began with such a journey. In 1987 a group of new converts to Orthodoxy started a skete in Ohio under the direction of Father Kallistos, a Greek came under ROCOR. They then branched to a parish-supported in the suburbs of St. Louis. But in 2000, a couple named Moe and Nadia Sill donated 120 acres of land to the brethren. The Sills had settled in that corner since the 1960s as they too were reclusive. Rumor has it that Moe Sill, a retired anthropology professor from Marshall University, used a self-made glider plane to get from the distant hill to their lone cabin on the property as there were no roads to reach the property. Igoumen Serafim, the spiritual father of the community, brought a group of six monks with him to live on the property. Slowly it expanded both physically and spiritually. Now it numbers 25 monks, not counting two more in the Skete of St John in Ohio, and 180 acres; it clocks 2,000 visitors a year.

Indeed, the diversity of the brethren is unique for an isolated corner of forgotten Appalachia. On my visit, I spoke to a young monk on the phone with a distinctive English accent, who alas could not give me directions because he did not drive. The monk making incense heralded from Japan; some monks were of Russian descent, others Greek, but the majority were American. The guest master Father Hilarion, a late convert in his early 30s, described the journey that many of the monks took to arrive at the Hermitage:

“People from all different backgrounds come to the monastery, especially young people not necessarily raised in Orthodoxy. Nothing in the world would lead one to the monastery except for God’s Grace. These young people follow the ways of the world to their ultimate conclusion and realize it is just an emptiness. They are searching for meaning and a meaningful life and then they discover this place called a monastery and there is an attraction because it is a place they can come and pray and search for Christ and be separated from the distractions of the world.”

Father Hilarion was raised a “double pre-destination Calvinist” who spent some time searching for different religions and philosophies in college. When he discovered Orthodoxy, “it was everything I was looking for and didn’t really know it,” he recounts. “It was all unified and transfigured in Christ.” He converted a few years after graduating from college and joined the monastery a few years after that.

Even as a teen he had done a lot of reading of the Transcendentalists, especially Thoreau. The seed idea of going out and not following the general rat race and the expectations of society but searching for a meaningful life, “to live deliberately” as Thoreau coined the phrase was deeply embedded in him. Yet unlike Thoreau who turned his back on the world, Father Hilarion cautions that is not the vocation of the monk. “People tend to think of monks as being useless or worthless but that is because people do not believe in the power of prayer,” he says. Monastics have walked away from the world not to discard it but to find a way to focus their energies on prayer away from its distractions. “We leave the cities to come to the desert not because we are turning our backs on the world but so that we can be closer to Christ and pray for the world,” he continues. Prayer is essential, he explains, and because it is more focused in the monastery its effects can be greater. He used the analogy of a pebble dropping in the center of the lake with the ripples of water growing larger and larger affecting the entire body of water.

The ripples of influence are not lost on the surrounding community. Many local converts have been made, predominantly “country Baptists.” The locals have accepted the monks as men who love Christ very much and take the life of prayer seriously. When they see a black cassocked figure buying groceries or running errands, they approach and give them prayer requests. In fact, a long-time resident, the founder of the Heritage Museum, a replica of an original Appalachian town complete with school house outside of Huntington, the closest city, has made his opinion very public that it was not by accident that God led them to establish a community devoted to prayer in a place riddled with blight and meth addiction. He along with other locals feel their prayers have effected a positive change in the surrounding community.

The Hermitage of the Holy Cross also extends community across Orthodox denominations. From its inception, says Father Hilarion, it has been Father Serafim’s vision to cultivate a pan-Orthodox union even before ROCOR unified with the Moscow Patriarchate. The monastery keeps close ties to other Orthodox churches: the Antiochian Cathedral of the Holy Spirit in Huntington and Lexington, Kentucky; St. George’s and St. John’s both Greek; as well as other Russian and Bulgarian churches from West Virginia. “We might have our different traditions,” Father Hilarion says, “but we are one big Orthodox family.”

While its principal focus is maintaining a liturgical life of prayer in the Russian tradition, the monastery maintains itself by operating a very successful soap shop, incense workshop, and bookstore, the majority of whose sales come from online. The soap room is run by a young woman named Anne, a convert from Nova Scotia. As luck or providence would have it, she was a professional soap maker back home. But once she and her husband converted, they too began a search to find an Orthodox community to belong to as there were none in Nova Scotia. On the recommendation of another monk they visited the Hermitage and realized very quickly this was the place. They sold their home and moved. At that point, the lone monk of the soap division could not keep up with demand; Annie, a professional soap maker, was hired to take his place and has been there making all sorts of soap from 9 to 5 for the past eight years. She makes both liquid and bar soaps using goat milk provided by the herd of donated goats on the property and all natural oils such as olive, lanolin, and coconut.

Anne, a convert to Orthodoxy from Nova Scotia, runs the soap making workshop full-time. She was a professional soap maker in Canada.

Anne, a convert to Orthodoxy from Nova Scotia, runs the soap making workshop full-time. She was a professional soap maker in Canada. “Everything fits together. The more we read, the more we realized we were looking for the early church. Tradition in Protestant thinking is such a bad word because it is understood as passing down by man and is therefore man-made. But in Orthodoxy, tradition refers to the Church’s original teachings. It is what the Church taught from the beginning. When the Apostles were chosen by Christ, they were filled with the Holy Spirit, they had the whole truth. It wasn’t just little sections and throughout the years they learned more and now we know more than they did; that’s not how it happened. The Apostles knew from the beginning. They had the fullness of Truth and that truth is still here with us today. For me once I figured it out where else would I want to be?”

My visit also included an eyewitness account of its thriving incense workshop. The fragrance from the workshop permeates the buildings and street around the monastery like a cloud. The Hermitage of the Holy Cross is famous for the over 25 varieties of incense it produces, from honeysuckle to Flowers of Cyprus, Old Church, and Lindisfare. Genuine frankincense is shipped directly from Somalia and Ethiopia, the type that oozes from the tree, which surprisingly carries no odor. Then they mix this with incense fragrance powder in an industrial-sized mixer. The substance comes out in a huge gummy mass which is then pressed and run through an incense cutter, once one way and again at a 90 degree angle producing the familiar chunks of incense. It is then cured for at least a month, but most batches settle for at least six months, so it can harden. The workroom is caked in a fine white layer of incense powder that gives it the look of a winter wonderland with a sweet smell. During the busy season, two batches of incense are made per day to keep up with demand. That amounts to 26 pounds of incense per day!

After coming out of the industrial mixer, the frankincense mixed with the powder comes out a gummy substance.

After coming out of the industrial mixer, the frankincense mixed with the powder comes out a gummy substance.

For the tempest-tossed denizens of the post-modern world, the one blinking, beeping, always online, responding to every stimuli but doing nothing; the 24,659 emails that need responding to, always going going going but never present post-modern world, the solitude of the woods is a panacea. How glorious to walk out just as the glow of dawn haloes the hills and—breathe! The orioles echoed madrigals one to another just as in the mystic candlelit church the monks sang their morning hymns. Living through the rhythm of a monastery, even for only one 24-hour cycle, one’s soul is filled with the stillness, the open space, the silence, the darkness. Contrary to expectation, it is precisely in these elements, those that are most avoided in the cities, that one can truly hear the whisper of the Word. Only when one silences both the external and the internal noise can one hear the voice of God whispering in her soul.

One makes the long pilgrimage to a monastery to seek some spiritual truth. You go on a wing and a prayer. And in the silent majesty of the evergreen spires, you will hear the whisper of the Wisdom of God. In the silence you will hear His voice. And you will gain the answer you seek. Perhaps it was buried deep within you pressed by the burdens of earthly cares like the weight of so much earth.

Walking through the woods of the Hermitage of the Holy Cross, the answer I was looking for rebounded ever more clearly. I too had to change my life; I too had to resolve to live life deliberately. I made the decision to leave the rat race behind and find a secluded section of wood to write, to pray, to be. Sometimes to save your life, you have to simplify it.