Source: Russian Culture

March 11, 2016

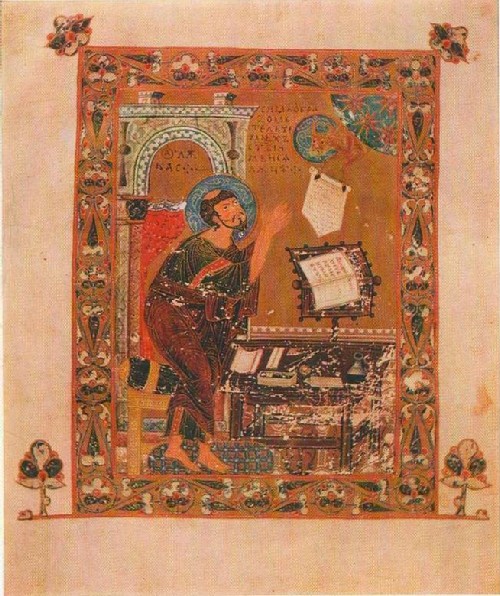

The art of book design has an interesting and rich history. For centuries, books were created by talented artists manually, commissioned by wealthy people. Each hand-written book took several months, and even years of hard work. Particular skill and care required work on the “facial” manuscripts – the so-called books decorated with miniatures, illustrations and ornamentation.

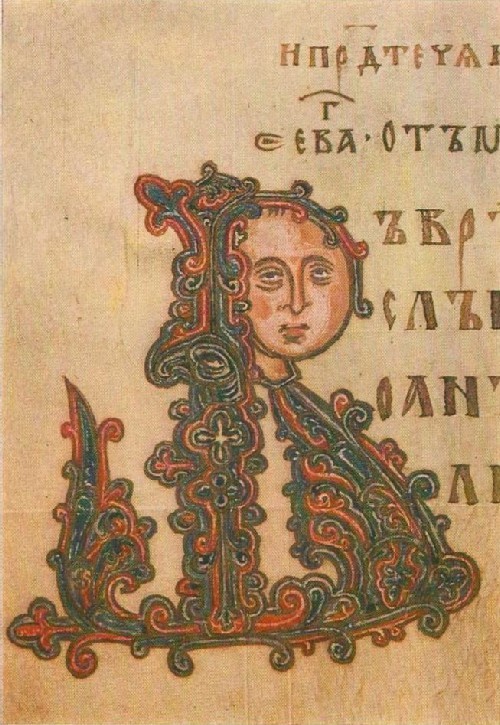

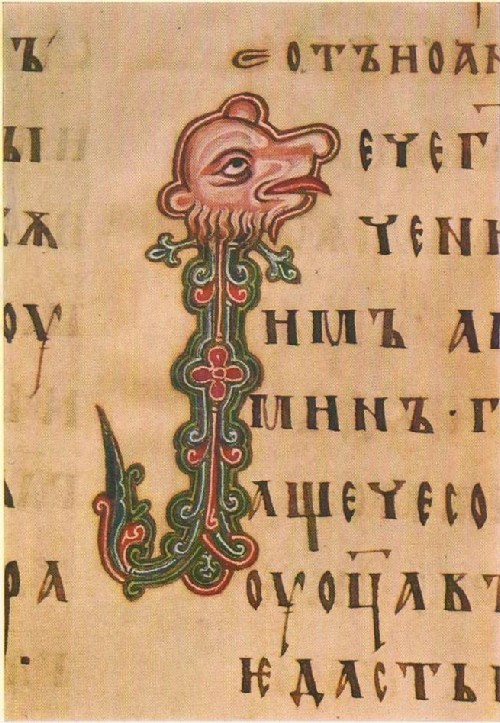

In ancient Russia book writing arose in the XI century and the first few manuscripts (for example, the famous “Ostromirovo Gospel”, 1056- 1057) demonstrate an amazing performance, excellence and a rich fantasy. The material for writing till the XV century was vellum (specially processed leather). Tight sheets of parchment were sewn together in a notebook, and notebooks in a book block. Massive, leather bindings covered and protected the parchment from damage. The text was written with dark brownish ink, as a rule in two columns. No matter how expensive the parchment, the artist did not stint to leave wide margins. The page looked very beautiful and solemn, and the initial (capital letter) had to be big and intricate.

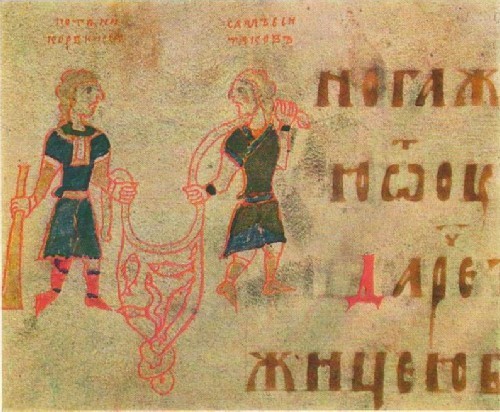

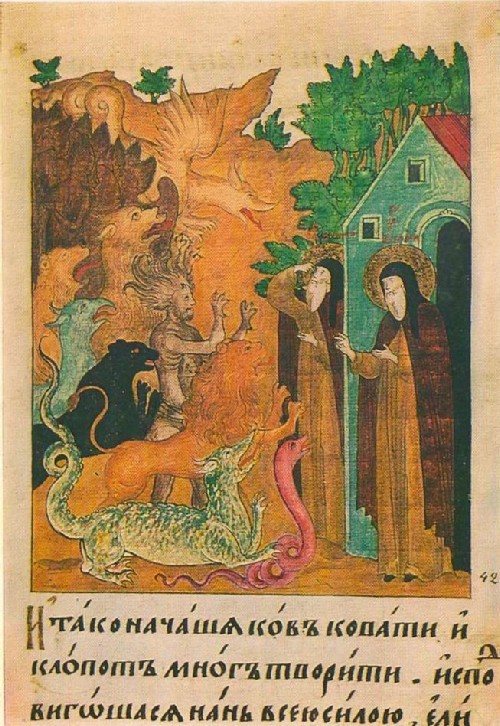

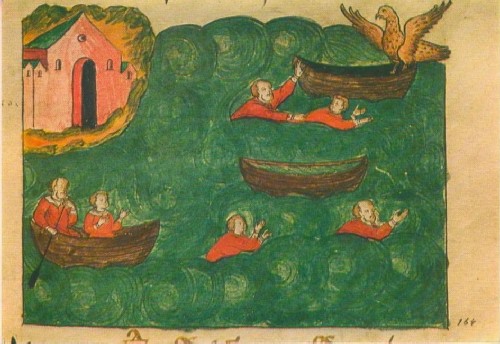

Paints used in ancient miniatures did not fade with time. In dense glossy parchment they froze in an opaque layer, shimmering deep sonorous tones of red, green, blue, and the light of the subtlest shades looked gentle pink, golden, and blue. Gold gave a special elegance and refinement to a miniature. Gradually the character of the books changed. Handwriting loses rhythm, clarity and turns into a powdered fluent cursive. In addition to large, full-leaf, there appears multi-story scenes, located directly in the text or in the margin. In the XIV-XV centuries they were not complicated in composition, drawn without a background. Scenes were often connected with the corresponding paragraphs of the text, which, incidentally, were no longer placed in two columns, but completely covered the page.

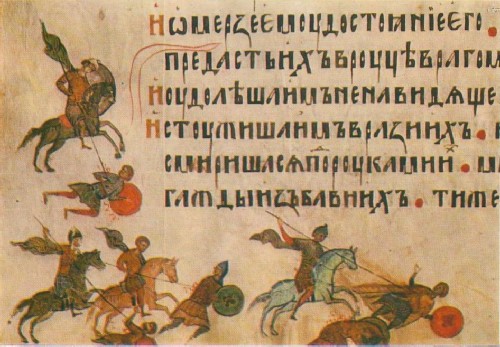

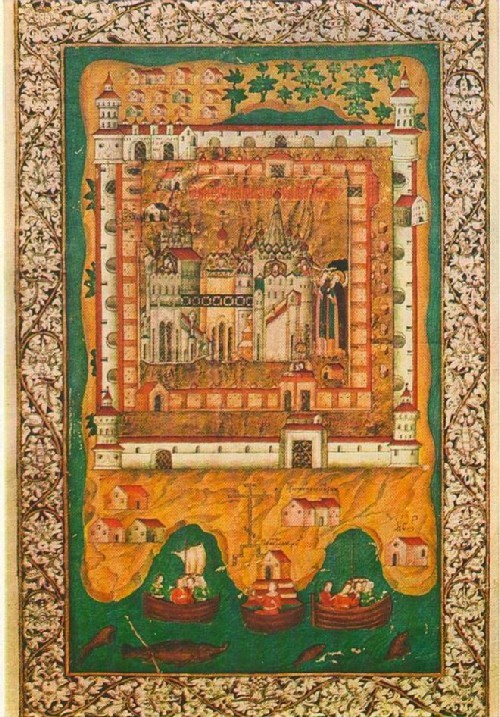

Battle between the army of Alexander Nevsky and the Livonian knights on the ice-bound Chudskoye Lake. 17th-century manuscript

Battle between the army of Alexander Nevsky and the Livonian knights on the ice-bound Chudskoye Lake. 17th-century manuscript With the advent of paper Russia (XV c.) changed the color scale of its miniatures. Paints, as if blurred, lost their enamel luster and vibrance and acquired watercolor transparency and lightness. Even the glimmer of gold was softer, muted. The growing interest in life, in the world was reflected in the miniatures, filling them with new content. Portrait miniatures were less constrained by formal requirements – the range of subjects became much broader than in the icon and fresco. Whatever the artist illustrated – historical chronicles, religious books or literary work, he always tried to make the miniature the result of his observations.

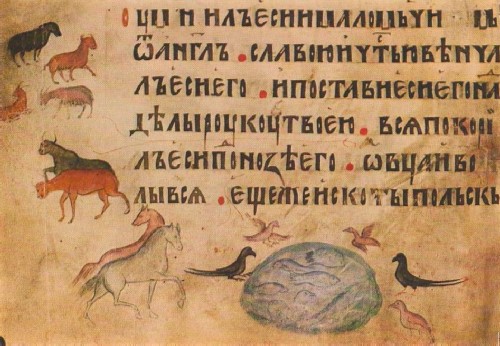

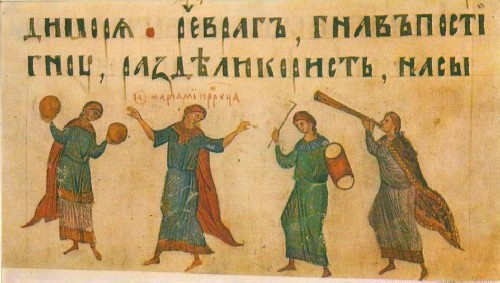

Letters were undergoing big changes. They increasingly became the living attitude and imagination of the master. Often caps took the outlines of animals, birds, snakes or fantastic monsters. And often in the initial scene there was depicted figures or individual fishermen, hunters, buffoons.

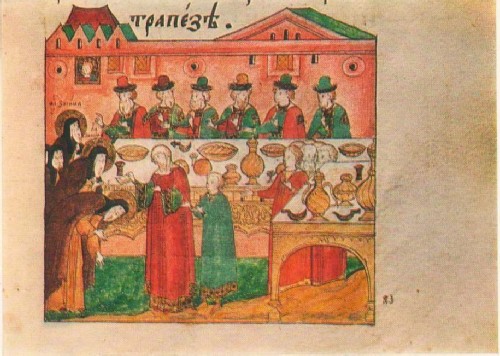

In the books of the XVI-XVII centuries, almost every page was illustrated, almost every page talked about everything – from the everyday lives of ordinary people to major historical events. Many stories reflected the theme of patriotic struggle for national independence, with which the history of the Russian people was full. The miniaturist with documentary precision depicted household items, tools, utensils, clothes, weapons, religious and secular architecture. Some scenes he showed in a humorous tinge. In the design of the book is reflected folk art, full-blooded and active.

In the 70-80s of the XVII century human images in miniature became more individual. In artistic techniques much attention was given to the transmission of light and shade and volume, and the complexity of perspective constructions. Often at the end of the manuscript artists left a record of where and when the book was created, by whom and at whose request.

Taken from life, the characters, narrative story, and familiar realities helped the medieval reader specifically to accept the contents of the book; for us, these miniatures are an inexhaustible source of the study of life, lifestyle, and the appearance of our ancestors. Handwritten books have not escaped the ravages of time, wars, fires, and sometimes human ignorance. No wonder that to our day there has survived only a small part of a huge manuscript heritage. But what remains indicates a high level of literariness in ancient Russia, and of the talent and genius of the masters. The ancients said: “The hand holding the pen will decay, but the written lives forever.”

After the Great October revolution, most monastic libraries and books from private collections, as outstanding monuments of national culture, were moved to the state repository. One of the richest collections of ancient manuscripts is in the State Public Library named after Saltykov-Shchedrin in St. Petersburg.