With the push for a pan-Orthodox acceptance of the Pre-Synodical text, “Relations of the Orthodox Church with the Rest of the Christian World,” a century long process of distortion of Orthodox ecclesiology is coming to fruition. Insomuch as the Pan-Orthodox Council accepts the erroneous teaching that heretical ministrations are mysteries of the One Church, so much so will it acquiesce to the adoption of a new ecclesiology.

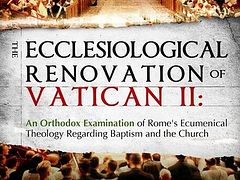

In this lecture, in the brief time allotted me, my intention is to succinctly present the origins of this erroneous teaching, two of the pillars of the new Vatican II ecclesiology which largely rest on this teaching, the adoption of this error by Orthodox ecumenists and the attempt to secure pan-Orthodox reception of it via the pre-Synodical text on the heterodox.

- The Post-Schism, Western Origins of the Acceptance of Heretical Baptism Per Se

The historical origins and development of the idea that the Church shares the “one baptism” with heretics, and that, indeed, this is the basis for recognition of the “ecclesial nature” of heresy, lie exclusively in the West, and indeed in the post-schism West. Although it cannot be denied that the peculiar Latin sacramental theology owes much to Blessed Augustine, the decisive break with the patristic consensus on heretical baptism came with the views of Thomas Aquinas.

Thomas Aquinas, in developing the medieval doctrine of Baptismal character[1] cites Blessed Augustine as his main source. Aquinas’ use of the term "character" is, however, quite different than Augustine’s. For Aquinas, "character" is an indelible mark on the soul,[2] which can never be removed.[3] For Augustine it is an external sign. He is “referring quite literally to a mark on the body, and using it as an analogy to explain the validity of the sacred sign of Baptism.”[4] His theory is based upon the idea that the external sign of Baptism can be possessed by someone who is actually internally alien to the body of the Church and so bereft of the sacrament’s effectiveness. This difference has grave implications for the meaning of sacramental efficacy.

For Aquinas the Baptismal character produces spiritual effects and is sealed on the soul of all who are validly baptized. The sign, therefore, simply on account of being externally valid brings about an enduring effect on the soul. This is exactly what does not happen in Augustine’s theory: valid sacraments can be and many times are totally without spiritual efficacy.[5] In this teaching of Aquinas we may have the first step toward the full, conciliar acceptance at Vatican II of the presence and workings of the Holy Spirit in the mysteries of the schismatics and heretics.[6]

As with Augustine, whose “new theology” of the church was intended as a guarded development of the patristic concensus expressed before him, but who nevertheless laid the first foundation stone for much greater innovations, Aquinas can also be said to have laid the groundwork for later theological development.

In his Summa Theologie, question 64, answer 9, Aquinas does maintain in principle what Vatican II will later abandon with regard to the “separated brethren,” namely the Augustinian distinction between the “sacrament” and the “reality” of the sacrament. Therein he states that there are heretics who “observe the form prescribed by the Church” and that they “confer indeed the sacrament but not the reality.” He is referring, however, as he stresses, to those “outwardly cut off from the Church,” such that one who “receives the sacraments from them, sins and consequently is hindered from receiving the effect of the sacrament.” It is important to stress here, that their sin in receiving the sacrament from known heretics is what obstructs their reception of the reality, not the impossibility of the sacramental reality being imparted outside of the Church.

Aquinas writes that anyone who receives the sacraments from one excommunicated or defrocked “does not receive the reality of the sacrament, unless ignorance excuses him.” Thus, for Aquinas, the obstacle to efficaciousness and the reality of grace in the mystery is not necessarily the lack of unity, as Augustine would have it, but knowingly participating in the sin of disobedience and rebellion. “The power of conferring sacraments” remains with the schismatic or heretical cleric, such that one ignorantly receiving Baptism from him has not only received a true sacrament, but has also received the spiritual reality of Baptism, which includes initiation and incorporation into Christ.

Aquinas writes the same in his Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, holding that “heretics and those cut off from the Church confer true sacraments, but that no grace is given, not from defect in the sacraments, but because of the sin of those who receive sacraments from such against the prohibition of the Church”[7]. This is the most crucial point and that point which separates post-schism Catholicism from Augustine and the pre-schism Church in the West. When, later with Vatican II’s re-evaluation of schismatics and heretics as “separated brethren,” the Council will not only lift any such prohibition but even encourage limited intercommunion, then the “life of grace” will be seen as springing from the dissidents’ liturgical life and prayer, a life which opens up access to the assembly of those being saved (Unitatis Redintegratio 3c).

It is precisely on this point of efficaciousness by way of ignorance and in seeing “character” as the sign of ecclesiastical membership that the fashioners of the new ecclesiology will form their new view of schism, heresy and the church. Aquinas provided, as it were, the building blocks with which to shape the new vision of the Church. The most important of these is that which would have every valid sacrament producing spiritual effects for all but those who knowingly commune with schism and heresy. Hence, following Aquinas, Bernard Leeming could state, even in 1960, before the advent of Vatican II, that “if the sacrament is valid, its fruitfulness depends exclusively upon the disposition of the recipient.”[8]

- Two Essential Characteristics of the New Ecclesiology at Vatican II

Nearly seven centuries of important modifications to Latin sacramental theology and ecclesiology would pass from the concise references of Thomas Aquinas to the “new vision” of the Church at Vatican II. During the middle ages, the once given unity of the mysteries, both practically and theologically, was lost, such that baptism alone came to be regarded as sufficient for initiation into the Church.

However, it wasn’t until the advent of ecumenism and the trail-blazing boldness of one thinker, “the father of Vatican II,” Yves Congar, that the seed planted by Aquinas would sprout forth into the ecumenical tree that is the new ecclesiology.

Already in 1939, in his seminal work, Divided Christendom,[9] the French Dominican theologian laid down the pillars of the new ecumenical ecclesiology which would be proclaimed at Vatican II and adopted in the ecumenical movement.

- Ecclesial Elements

Congar “affirmed that ecumenism begins when we start to consider the Christianity not just of schismatic Christian individuals, but of schismatic ecclesiastical bodies as such.”[10] On the basis of this innovative approach, he was then led into other innovations, namely, “to put forward his own version of the concept that the schismatic communities retained elements of the Una Sancta in their schismatic situation.”[11] Moreover, if these elements, chiefly the holy mysteries, first of which is Baptism, preserve “through good faith” “the essential[s] of [their] efficacy,” they bring about in the soul of the dissident “a spiritual incorporation (voto) in the Church,” making the dissident a member of the Church, tending toward “an entire and practical incorporation in the ecclesiastical Catholic body.”[12]

It is this critical assumption, that “elements” of the Church, such as Baptism, can be extracted from the whole and still have life to give, which underlies and supports the entirety of the new ecclesiology. Far from being a return to the Fathers, this theory of autonomous ecclesiastical elements has its origins in none other than John Calvin’s doctrine of vestigia ecclesiae, which Congar developed with a slight change of emphasis.[13] In his theory, the schismatic and heretic is made a member of the Church on the account of the "baptismal character," in spite of lacking an orthodox confession of faith, full sacramental life or communion or unity in faith and love. Congar writes: “In this way it is that the Church includes members who appear to be outside her. They belong, invisibly and incompletely, but they really belong.”[14]

- Recognition of the “Ecclesiality” of Heterodox Confessions

It is a very short step from recognition of “ecclesial elements” among the heterodox to recognition of the “ecclesiality” or “ecclesial nature” of heterodox confessions. This step was easily taken at Vatican II.[15] It is now a step that Orthodox ecumenists would like the Pan-Orthodox Council to take.

Allow me to quote a prominent theologian and interpreter, Johannes Feiner, to describe the celebrated “communio” ecclesiology of Vatican II, which will make it clear what recognition of “ecclesiality” means in post-Vatican II ecumenism:

Because the Church is seen as a “communio,” or a “complex reality in the form of a communion, the unity of which has been brought about by numerous and various factors, the possibility remains open that the constituent elements of the Church may be present even in Christian communities outside the Catholic Church, and may give these communities the nature of a Church. Thus, the one Church of Christ can also be present outside the Catholic Church, and it is present, and also, indeed, visible, in so far as factors and elements which create unity and therefore the Church are here.[16]

This, then, is the purpose of recognizing elements of the Church, such as baptism, outside of the Church, and also the ecclesiality of the heterodox: in order to broaden the Church such that the Orthodox Church is not identified exclusively with the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.

Indeed, the aim of the introduction at Vatican II of the incendiary phrase subsistit in to replace the earlier formula est, which expressed a strict identity between the One Church and Catholicism was to differentiate between the Church of Jesus Christ and Catholicism. The new phrase was meant to say that, while the Church of Christ is really present or concretely real and is to be found in Catholicism, it is not to be strictly identified with it.

A similar effect has been achieved in the consciousness of many Orthodox with the widely heard phrase first made popular by Paul Evdokimov and later through Metropolitan Kallistos Ware’s works: “We know where the Church is; it is not for us to judge and say where the Church is not.”[17] This sort of apophatic, almost agnostic, view of the Church was, not surprisingly, influential in the formation of the new ecclesiology of Vatican II.[18] It appears to be connected to a gross, out of context misreading of St. Irenaeus’ famous phrase “For where the Church is, there is the Spirit of God; and where the Spirit of God is, there is the Church.”[19] Although the Saint spoke these words in the context of juxtaposing those with “perverse opinions” with the “apostles, prophets, teachers” and mysteries through which the Spirit works in the Church, his words are taken out of context to claim that wherever (and in whatever manner) the Spirit works (among the heterodox especially) the Church is present making members.[20]

This inversion of St. Irenaeus’ view of the Church is consistent with the ecumenists’ refusal to identify the canonical and charismatic boundaries of the Church,[21] which was certainly the patristic consensus of the ancient Church,[22] without which the canons lose their meaning and force.[23] In light of these views, it is not surprising that some have ceased viewing the Church as the continuation of the Incarnation.[24] At the root of these innovations lies an inability to crucify the intellect and accept “the scandal of the particular,” but also a failure to explain in terms consistent with Orthodox incarnational ecclesiology the nature of the work of the Holy Spirit outside of the Eucharistic Synaxis.[25]

The new image of the Church which has emerged, on the basis of the recognition of the “ecclesiality” of the various Christian confessions, is well-described by Jesuit scholar Francis Sullivan:

one can think of the universal Church as a communion, at various levels of fullness, of bodies that are more or less fully churches…. it is a real communion, realized at various degrees of density or fullness, of bodies, all of which, though some more fully than others, have a truly ecclesial character.[26]

It is crucial to have this idea of the Church in mind when reading the pre-synodical draft text “Relations of the Orthodox Church with the Rest of the Christian World.” In the warped ecumenical ecclesiological framework of post-Vatican II ecumenism, the mere identification of the Orthodox Church with the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church does not preclude the simultaneous recognition of other Churches as possessing an “ecclesial nature” or even as being “more or less fully churches.” Such an unorthodox reading is, of course, quite likely when the text makes particular references to heterodox confessions as “churches.” In a dogmatic text of this nature it should be obvious that the term must be used strictly in accordance with the Orthodox meaning of the word, so as to exclude any possible misinterpretation.

Given the unorthodox ecclesiological paradigm of post-Vatican II ecumenism, there is sufficient basis for the hierarchs of the Local Churches to reject the draft text on relations with the heterodox. If, however, we also consider the views of leading ecumenist theologians among the Orthodox, some of whom have been involved in the drafting of the pre-Synodical texts, there is pressing need for a condemnation of the new ecclesiology, lest the heterodox notions of the Church be accepted as Orthodox.

- The Adoption of Key Components of the New Ecclesiology by Orthodox Ecumenists

Although lacking the developed sophistication found in Vatican II, the ecclesiological views of leading ecumenists find agreement with their Latin counterparts in the fundamentals of the new ecclesiology. The two foundational characteristics of the new ecclesiology referred to above—the recognition of heterodox baptism per se and the subsequent recognition of the “ecclesial nature” of heterodox confessions—have been embraced by today’s leading ecumenists, such as Patriarch Bartholomew, Metropolitan John Zizioulas, Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, Metropolitan Chrysostom of Messenia, Professor Stylianos Tsompanides, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, Professor Michel Struve, and others. Here I can only briefly refer to the most representative voices, focusing mainly on the views of those theologians directly involved in the drafting of the pre-synodical document.

His All-Holiness, Patriarch Bartholomew, the main protagonist in the calling of the Pan-Orthodox Synod, has consistently expressed himself, both in word and deed, in harmony with the new ecumenical ecclesiology.[27] Accordingly, following the Balamand Agreement, he declared with Pope John Paul II that the Orthodox Church and the Papacy are “Sister Churches, responsible together for safeguarding the one Church of God” and called upon all Orthodox to recognize that we share with the Latins a common baptism and sacramental life.[28]

The de facto division of the Church, which flows from the acceptance of a common baptism and common Eucharist, was also stated cataphatically by the Patriarch as recent as 2014 in the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. There, he preached bare headed the pan-heresy of the new ecumenical ecclesiology, which posits a divided Church and a multiplicity of partially true churches. He presented clearly a major tenet of the new ecclesiology, namely, that the One Church does not exist today exclusively within one or another Church, and that in spite of having lost the unity of the Faith the separated Churches are still one.[29]

Please note that, like the pre-synodical draft text, the Patriarch states two contradictory ideas: that the Church is one, apparently only outside of time, and yet it exists in separated local churches. This supposed paradox is a cornerstone of the new ecclesiology which rejects the so-called “ecumenism of return” and insists on the “ecumenism of integration.”[30]

The most notorious example of such an “ecumenism of integration” is the Balamand Agreement. At Balamand, the recognition of mysteries and “ecclesiality,” essentially the same divided but somehow still united church ecclesiology held by the Patriarch and apparent in the pre-synodical text in question, was embraced.[31] This is what led Fr. John Romanides to refer to Balamand as a sequel to Vatican II.[32]

Numerous “common Baptism” agreements in the same ecclesiological vein have also been signed since Balamand by the Ecumenical Patriarchate, most notably in Germany, Australia and America.[33]

The ecclesiological views of the chairman of the Pre-Synodical Commission, the Metropolitan of Pergamon, John (Zizioulas),[34] unfortunately leave no room to doubt that he has embraced the new ecumenical ecclesiology. In his view the boundaries of the Church are not set in the blood of Christ, i.e. the Eucharist, but in the waters of Baptism, on the basis of “Baptismal unity.” “Within Baptism,” he wrote, “even if there is a break, a division, a schism, you can still speak of the Church.” The Orthodox, he believes, “participate in the ecumenical movement as a movement of baptized Christians, who are in a state of division because they cannot express the same faith together.”[35]

Another member of the drafting committee of the pre-synodical text, Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev) of Volokolamsk, has also expressed views in harmony with the new ecclesiology. He does not believe that there are fundamental differences between Orthodoxy and Catholicism.[36] He has said that, “to all intent and purposes, mutual recognition of each other’s Mysteries already exists between us.” “If a Roman Catholic priest converts to Orthodoxy [in Russia], we receive him as a priest, and we do not re-ordain him. And that means that, de facto, we recognize the Mysteries of the Roman Catholic Church.”[37]

It is apparent that, despite the patristic renaissance of the early 20th century,[38] Metropolitan Hilarion and the leadership of the Moscow Patriarchate are still working within the pre-revolutionary Russian ecclesiological paradigm heavily influenced by Latin scholastic thinking.

Metropolitan Chrysostom of Messenia, representative of the Church of Greece to the pre-synodical meetings, along with Stylianos Tsompanides, Professor of Theology at the Theological School of Thessaloniki, have given us the most direct insights into what the ecumenist-minded theologians understand our text to be saying. Both maintain that in referencing the 7th canon of the 2nd Ecumenical Council and the 95th canon of the Quinisext Council paragraph 20 of the pre-synodical text supports the “‘kat’oikonomian’ recognition of the ‘reality’ and ‘validity’ of Baptism” among the heterodox."[39] Professor Tsompanides also claims that this recognition “has significant consequences for the way we look at the ecclesiastical state of other Churches and other Christians,”[40] thus following Congar and Vatican II in connecting recognition of Baptism with recognition of “ecclesiality.”

- The attempt to secure pan-Orthodox reception of per se recognition of heterodox baptism via the pre-Synodical text on the heterodox

We must consider closely the very problematic phrase used by both Metropolitan Chrysostom and Professor Tsompanides, “‘kat’oikonomian’ recognition of the ‘reality’ and ‘validity’ of baptism of the heterodox.” The canons cited in paragraph 20 do not contain this phrase. In fact, none of the canons of the Church having to do with the reception of converts contain this phrase. Indeed, none of the canons even refer to “recognition of baptism,” let alone “‘kat’oikonomian’ recognition.” What do the canons refer to?

The reference point for the correct interpretation of those canons dealing with the “kat’oikonomian” reception of heretics is Saint Basil the Great’s 1st and 47th canons. In his first canonical epistle, St. Basil, after explaining why various schismatics (Cathari, Encratites, and Hydroparastatae) ought to be baptized upon their return to the Church, still allows for oikonomia, if need be, saying: “Nevertheless, since it has seemed to some of those of Asia that, for the sake of management of the many [οἰκονομίας ἕνεκα τῶν πολλῶν], their baptism should be accepted, let it be accepted [ἔστω δεκτόν].”[41]

The canon speaks of accepting, not recognizing, the baptism of the schismatic. There is a significant difference. The first, acceptance, is used in the context of the return of particular persons in repentance, that is, with respect to pastoral management of their salvation. The second, recognition, as employed by Metropolitan Chrysostom and Professor Tsompanides, is used in relation to schismatic and heretical groups as such, that is, with respect to ecclesiology.[42] In the first instance, the context is the acceptance of a returning heretic, whereas in the second instance the context is the recognition of the baptism of the heterodox group per se. Hence, the phrase “‘kat’oikonomian’ recognition of the ‘reality’ and ‘validity’ of baptism” is an unacceptable and misleading mixture of pastoral theology with ecclesiology. There is no such thing as “‘kat’oikonomian’ recognition” of Baptism, only “kat’oikonomian" acceptance.

The phrase is also shown to be foreign to the patristic mind insomuch as it refers to recognition of the “reality” and “validity” of heretical baptism, that is, recognition per se. In the canons of the Church you will not find heretical Baptism referred to in this manner. For example, in his 47th canon,[43] Saint Basil attributes the practice of Rome in accepting certain heretics without Baptism to some need for oikonomia (οἰκονομίας τινὸς ἕνεκα), but nonetheless insists on Baptism, despite the fact that they baptised in the Name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. By at once allowing for oikonomia and yet calling for Baptism the Saint excludes the possibility of recognizing the Baptism of schismatics and heretics per se.

When, in later synodical decisions or patristic texts, during the second millennium, Latin Baptisms are referred to as valid, this, properly speaking, is referring to whether or not the form or τύπος of Baptism, namely three-fold immersion, had been retained.[44] The purpose of recognizing a Baptism as “valid,” that is, in the case of the Latins, as done by immersion, was to determine if the presuppositions for oikonomia existed, not to recognize it per se.[45] In exercising economy the Church does not recognize the “reality” of heretical ministrations,[46] but only examines its validity in the sense of retaining the apostolic form.[47] Therefore, there is no basis, and it is once again misleading and a departure from the Orthodox phronema, to speak of recognition of the “reality” and “validity” of heretical baptism. If there is talk of “recognition” of the ministrations of heretics it is only in the sense of it being validly, i.e. properly, carried out in the apostolic manner. This is for the purpose of determining the possibility—not the necessity—of reception by oikonomia, as is clear in St. Basil’s 1st and 47th canons.

The misunderstanding or rejection of the kat’oikonomian practice of accepting heretical or schismatic Baptism is at the root of the adoption of the new ecumenical ecclesiology among ecumenist-minded scholars. They fail to grasp that the oikonomia of the Church is essentially the freedom of the Church's Head to work salvation in the midst of the Church as He sees fit (if, indeed, it is oikonomia and not simply paranomia (illegality)). The Lord, Who said all must be baptized of water and of the Spirit (Jn. 3:5) to enter the Kingdom of God also said to the unbaptized thief on the cross, Today shalt thou be with me in paradise (Lk. 23:43). Moreover, many martyrs were baptized in their blood and not water, and others who were hung or died some other bloodless death. Thus, it is clear that the Lord is not bound by His own commandments and is free to work his divine oikonomia in the midst of His Church.

Yet, this is the key: in the Church. Oikonomia, which is not without presuppositions, can never be a basis for ecclesiology, just as the Lord's freedom can never be pitted against His own commandments. Oikonomia does not equal recognition of mysteries per se. This is, however, exactly what some of the authors of the text in question would like the pan-Orthodox Council to endorse. They are pushing for pan-Orthodox recognition of another vision of the Church, a heretical vision, that which has already been accepted by Vatican II and many in the WCC. Now it should be plain to all that rejection of the akriveia-oikonomia interpretative key of our pastoral practice leads inevitably to a heretical vision of the Church.

Fr. Peter with Fr. Theodore Zisis and Archimandrite Athanasius, the former Abbot of the Monastery of Great Meteora and Fr. Sarantis Sarantou.

Fr. Peter with Fr. Theodore Zisis and Archimandrite Athanasius, the former Abbot of the Monastery of Great Meteora and Fr. Sarantis Sarantou. Conclusion

Today the slippery slope of innovation has brought many ecumenists to recognize not only the Baptism of the heterodox but also their Eucharist.[48] On account of the unity of the mysteries, recognition of the Eucharist is the expected and logical outcome of the disconnection of the canonical and charismatic boundaries of the Church, which coincide and are manifest in the Eucharist. For, although formally the Orthodox Faith is still claimed as the sine qua non for the common cup, in fact, by recognizing heterodox mysteries, indeed even the Eucharist, per se, the unity of faith has ceased to be a prerequisite.

If the Pan-Orthodox Synod allows for an ecumenist interpretation recognizing heterodox mysteries and “ecclesiality,” the common cup will remain as but a formality. A union will already have been achieved, but it will necessarily be a false union, since not one heretical doctrine has been repudiated.

https://www.academia.edu/3051372/The_19th_Canonical_Answer_of_Timothy_of_Alexandria_On_the_History_of_Sacramental_Oikonomia

http://www.lulu.com/shop/pietro-chiaranz/la-contestazione-ignorata/paperback/product-23179353.html#

I hope this can be of help for understanding these delicate issues.

Sincerely.

At the next meeting in June, the Holy Rus’ hierarchies will stand by the Church or will fall for the world. In the latter case, their fate in the day of the Lord will be worse than Judas’.