Source: Mint on Sunday

April 10, 2016

Once upon a time, in a land far away, lived a queen named Ketevan. And centuries later, two governments, priests, archaeologists, historians and genomics researchers would work together to try and find a part of her body lost in the ruins of a Goan church.

The time, to be precise, was the early 17th century. The land, Kakheti in eastern Georgia, a hilly region known for its wine. Ketevan’s husband had died after ruling briefly, and her son Teimuraz was king, but as a vassal of the Persian Shah Abbas I.

Teimuraz was proving a less-than-ideal ruler of a dependent kingdom. He had flirted with the Ottomans and Russians, both rivals to the Persians. Abbas was threatening to invade Kakheti. In 1614, Ketevan offered herself as a hostage to Abbas in a failed attempt to prevent carnage.

She was held in Shiraz until 1624, when Abbas offered Ketevan, a grandmother in her 60s and a devout follower of the Georgian Orthodox church, the option of converting to Islam and joining his harem. She refused and was killed—strangled, after her flesh had been picked apart by red hot tongs.

In Shiraz at the time were two Portuguese friars of the order of St Augustine from whom Ketevan had taken some comfort. Since she was seen as having died for her religion, she was a martyr.

The Augustinians hoped that with a little finessing about how close she had been to becoming a Catholic, Rome might make her a saint. This would be strategically convenient for spreading the faith in Eurasian lands, which had well-established churches of their own.

For saints to be venerated, you ideally needed relics. So, the friars exhumed Ketevan’s body. In 1628, they took some of her remains to her grateful son, who had them interred at Alaverdi cathedral—and allowed the friars to open a mission in Georgia.

Ketevan did end up a saint, but of the Georgian church. Her remains were being moved from Alaverdi to a safer location amid raids on the region when the horse carrying the remains lost its footing and fell into the river Aragvi. The relics were washed away. Fragments of her body were thought to be in other places, but this much was known from contemporary accounts: her right arm had been taken to Goa in 1627 by Portuguese friars to be interred in the St Augustine complex.

The Augustinians left the complex in 1835, after which it collapsed in stages (to become what may be familiar to Hindi film viewers as the 1965 thriller Gumnaam’s eerie overgrown-by-forest structure through which the cast bemusedly wanders as the song Gumnaam Hai Koiplays). There was no record of what happened to Ketevan’s relic when the complex was abandoned.

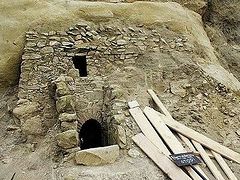

Today, the St Augustine complex is a spectacular ruin. A towering shard from what used to be a five-storey facade pierces the sky. Around it lies an expanse of laterite blocks, basalt slabs, masses of bricks, once-indoor tombstones bearing coats of arms.

It’s palpable—the grandeur of what must have been, and indeed the futility of grandeur itself. But to walk around the complex with Sidh Mendiratta—a researcher whose area of interest is at the junction of history, heritage and architecture—is to have it all come alive again.

He points out patches of faded red oxide work, sections of walls where the original azulejos tile-work has been restored. From weathered stone, he extrapolates to lives once lived here, to chambers in the convent where the monks ate, prayed and rested.

In the early 2000s, Mendiratta was a Portuguese exchange student studying architecture in Goa, when he visited the ruins. “It was love at first sight with the site,” he says with a laugh. (An enduring love too, for though he’s now a postdoctoral researcher at Coimbra University, Portugal, he returns when he can.)

Mendiratta ended up making the ruins part of his studies—his final project was to build a computer model of the complex in its prime. That brought him in touch with the Goa circle of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Beginning in the late 1980s, the Soviet Union and then independent Georgia began efforts to locate the Goan relic of Ketevan. This seems to have been prompted by the publication of a book in 1985 by Armenian historian Roberto Gulbenkian that for the first time brought together fragmentary accounts to present the story of Queen Ketevan.

Over the next 25 years, multiple Georgian delegations descended on Goa; the foreign minister of Georgia visited his counterpart Jaswant Singh and requested assistance in finding the relic; Georgian archaeologists conducted an unsuccessful excavation in the church complex; ASI teams looked for the bone without luck.

In 2003, Nizamuddin Taher of the ASI took over as head of the Goa circle. “It was my first independent charge,” he recalls. “I was not looking at any fresh excavations.”

His priority was to resolve certain administrative issues. For the St Augustine complex, his plans were limited to clearing some of the piled-up debris so that visitors could move about the complex. But the previous searches for the relic had got the locals excited.

“There was a romantic hype,” Taher says. “The story of Queen Ketevan was prevalent in Old Goa.” Taher’s colleagues were keen to work on the site, and then Mendiratta came along, asking to study the ground plan of the church. They started removing debris to make a transverse path in January 2004.

Where the relic of Queen Ketevan was concerned, previous teams were working from a single clue (probably obtained from a huge 1958 collation by Silva Rego of historical documents relating to Portuguese missions in the East). It stated that a black box containing the bones of Ketevan was installed on the second window on the epistle side of a chapel. The Georgian team, sure that it had to be the main chapel, had taken apart the area with such enthusiasm that it needed to be reconstructed with cement. They found nothing.

Taher and his team were not really looking for the queen’s relic as they continued clearing debris in 2004. Then, they found a basalt tombstone at the floor level under two metres of rubble. It had the name Manuel de Siqueira engraved on it. Mendiratta was intrigued. There was something familiar about the name, but he could not quite place it. He went to the library. “Sidh did not sleep that night,” Taher recalls.

It finally came to him. Mendiratta says, “The tombstone with the coat of arms is mentioned in an old chronicle as being in a place called the Chapter chapel.” It was in the 12th volume of Rego’s collation and it mentioned all the tombs in the St Augustinian complex. It said the Chapter chapel with the tomb of Manuel de Siqueira also held the black box with the Ketevan relic.

“I am very dispassionate,” Taher says. “As an archaeologist, bahut kahani sunte rehte hai... (we keep hearing stories...), but when this clue came in—we all had gooseflesh.”

It took work to identify the second window of the chapel on the epistle side. But when they looked under it—nothing. There was no trace of the sarcophagus. Mendiratta says, “We were both excited and disappointed. We were sure that we were in the right place, but the box was not there.”

They resumed work in 2005. Taher explains that excavation sites are covered in between seasons of work. When excavation resumes, “you remove the cover and you do brushing”. They had started on the brushing, when, “First thing—we get a bone.” It was just lying there, in two pieces. Taher’s colleagues were excited, but he was wary.

“It was out of context,” he explains. It was found a couple of metres away from the second window, and there was no trace of the box. To add to the uncertainty, they found two more bone fragments. And the lid of the sarcophagus, fallen on the other side of the window, but no trace of the box itself.

A Georgian delegation arrived in 2006, headed by father Giorgi Razmadze of Tbilisi’s St Ketevan church. They requested the relics be handed over to them. Taher asks, “How could we give them the bone unless we were sure it belonged to the queen?”

He felt genetic analysis may establish the provenance of the bones. Several laboratories in the US and Europe had been successful in obtaining DNA from old, unpreserved samples. But, Taher says, “It is difficult to send an archaeological antiquity to another country.” So, the analysis would have to be done in India. The trouble was—no ancient DNA studies had ever come out of India.

Taher got in touch with K. Thangaraj at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Hyderabad. Thangaraj had just started the first ancient DNA facility in India. He agreed to try and extract DNA from Taher’s samples.

We are made of cells; almost all cells contain DNA; a person’s DNA can be unique in the manner of a fingerprint. Hence, the use of DNA in placing people at a crime scene or establishing parentage. But how was DNA to prove useful with the old bones found at the St Augustine complex?

For starters, even obtaining DNA from the bones could not be taken for granted. Ancient DNA—that is, DNA from old, unpreserved specimens—is notoriously hard to work with. Thangaraj says, “There is no single protocol that works with all samples. We have to keep modifying the procedure for different samples.”

And then, even if the bones yielded DNA, what could it be compared with? There was a small relic claimed to be from Ketevan at the church in Tbilisi, but the history around it was murky enough that its own provenance could not be taken for granted.

Thangaraj and his colleagues decided to go at the problem by trying to extract from the bone samples a kind of DNA known as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). There are more copies of mtDNA in a cell as compared to the other sort, so it’s easier to work with when genetic material is not forthcoming.

The other thing about mtDNA is that it is usually passed down unchanged from mother to child. But on the rare occasion it will undergo a random change, and this will mark all the woman’s descendants from then on. The tag marking a new branch of descendants is called a haplogroup. Identifying haplogroups in a person’s mtDNA can help geneticists place her geographically, which is what the researchers hoped would happen with the bone samples they had.

“An archaeologist should never part with his samples,” says Taher. So, he went to Hyderabad in November 2006, carrying with him the bones wrapped in cotton. A CCMB team took samples and worked on them for almost three years but could not successfully amplify DNA from the bones.

Niraj Rai is a researcher at CCMB who worked on the bone samples from 2010 onwards. “The best source for ancient DNA,” says Rai, “is the tooth.” Then, in order, the bone of the inner ear, ribs, finger-bones, the skull and finally, the long bones. “Unfortunately, what I got was a long bone.” And even then, keeping the significance of the relic in mind, he had to work using only a tiny amount of bone powder.

Because it is so hard to obtain DNA from old specimens, and so easy to contaminate them with genetic material from people working in the lab, ancient DNA labs tend to be fortresses of a peculiar sort.

Take the ancient DNA facility at CCMB. It is in a building that houses lab animals to keep it away from other labs with human DNA. The building itself has a retractable staircase—Rai has to press a button so the flight of steps reaches the building. (This is apparently to keep snakes from snacking on lab animals.)

Then, footwear must be changed at two points before getting to the lab and protective clothing worn. The air-circulating system is such that filtered air flows outwards from the lab and then the chamber beyond. Outside is a list of almost comically stern instructions, including one that says all pens and calculators that enter the lab must have been irradiated in UV light for at least two days.

For their second attempt, the CCMB team had refined their technique and had access to better equipment. This time, they were successful in sequencing mtDNA from the bone samples. The first bone that had been recovered from the St Augustine complex had a haplogroup—U1b—they had never seen in contemporary Indian DNA samples. They wanted to compare the sequence with mtDNA from modern Georgians.

The St Ketevan Church in Tbilisi swung into action and shipped over saliva samples from 30 east Georgians. (Perhaps never before has a religious establishment been such a willing partner in a scientific investigation.) Some of them had the U1b haplogroup, showing it was prevalent in the region.

The other two bone samples had haplogroups typical of western India and likely came from locals. Additional tests confirmed that the U1b bone came from a woman. So, in 2013, it was established that the bone found in two pieces in 2005 was consistent with being from a Georgian woman.

It was the first time an ancient DNA result was being reported from India. When Rai, Taher, Thangaraj and their colleagues tried to publish their findings in a scientific journal, they were asked to verify their work by repeating it in a different lab.

Thangaraj points out that this is a fairly standard precaution with ancient DNA results. “Unfortunately, there is no other lab in India,” he says. The researchers argued that contamination was unlikely because the U1b haplogroup they were reporting had not been seen in India in the more than 20,000 samples they had in their database.

The journal did not relent and the paper, titled Relic excavated in western India is probably of Georgian Queen Ketevan, was published in another journal—Mitochondrion—which agreed with their reasoning.

As the “probably” in the paper’s title suggests, it still cannot definitively be said that the bone belonged to Queen Ketevan, but as Taher puts it, the combined weight of “history, literary documents, archaeological excavations and genetic analysis” point to it being so. “Our work is over,” he says.

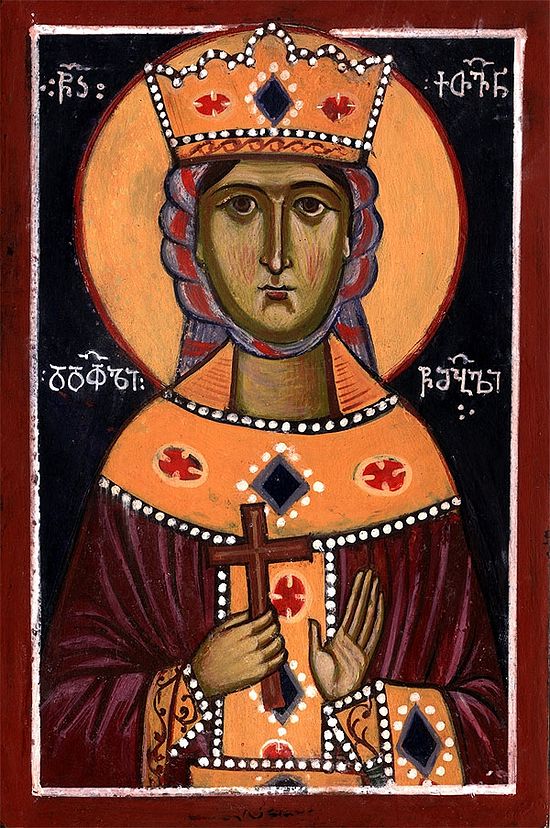

But what is definitive, anyway? At the Archaeological Museum at old Goa is the image of a haloed, determined-looking woman wearing a small crown. And in front of her is a glass box with two brown tubules. A placard says they are the relics of Queen St Ketevan of Georgia.

I’m thrilled to think of the human drama they have been connected with. I ask the museum in-charge if they are original. He says, “If we keep the original there, I will have to hold a lathi and stand next to it day and night.”

He enjoys a laugh at my naivete, then continues. “If anything happens to the bone, first the excavators will get a heart attack. Then, I will get a heart attack.”

Asked where the relic is now, Taher says, “It’s somewhere in India. We do not disclose the location.”

Relics are believed to possess an aura. Even independent of the religious dimension, Ketevan’s certainly does. Perhaps it comes from the combined light of being many things to many people.

It is an object of veneration to the Georgians, something that is no doubt redoubled by their having expended resources and emotion in its pursuit. To the archaeologists, it is the significant discovery that can come along only a few times in a career that involves such painstaking, meticulous work. To the Indian scientists, the relic is associated with their first result from a technique that is expected to make major contributions to what we know of our past.

And it must mean something to the organizers of the Ketevan Music Festival that began this year—with some of the concerts held in the St Augustine ruins.

In 2010 a filmmaker and artist named Gayatri Kodikal went to the St Augustine complex to shoot the ruins. The ASI was at work and the site was closed. She got talking with some of the archaeologists and heard about Queen Ketevan and the relic. “I was hooked on the story,” she says.

Since then, her obsession with the tale has taken her to Georgia and Portugal to visit archives and see places, people and artefacts related to the story. Currently, it is the inspiration for a board game she is creating. It’s called The Travelling Hand.

The queen’s post-mortem travels may not be finished yet. Talks are on between the governments of India and Georgia, and who knows, it may not be long before Queen Ketevan’s travelling hand finally reaches home, 400 years after she left for Shiraz.