In my school years every summer I went to grandfather Misha (a diminutive form of the name Michael) and grandmother Tamara in Digomi, Georgia, where they had a big house in which the first two years of my life passed. It stood on a slope of a mountain with a large garden that stretched over it. Rose trees, peaches, pomegranates and walnuts grew right near the veranda under the tiled roof, with vine twining around it. Vineyards, apple trees, pear trees, fig trees skirted an icy-cold brook, with greenhouses where thin long cucumbers and huge “bovine heart” sweet tomatoes grew. On another side there were oak trees, wild plum trees, hazel trees, and brambles.

After dinner grandfather Misha would go to the veranda with big sea binoculars and examine the opposite slope of the mountain and make some marks in the map with his pencil. Thus our hunt for white mushrooms, or porcini (an edible mushroom with a smooth brown cap, a stout white stalk, and pores rather than gills, growing in dry woodland and sought after as a delicacy) began. My grandad would look out for their dark-brown caps peeping out of hard grass and mark the spot. Then he would put on his dark-blue cap which covered his thin tanned face with the pointed nose along with a cowboy shirt, take a woven basket and call me. We would walk down a path of stones through the garden, cross the stream (which turned into a small ringing river beneath the mountain) on stones and climb on the opposite slope.

My grandad always unmistakably found mushrooms using the signs known only to him. I worked my way through bushes, cut off a big handsome white mushroom and squeezed my way through. Usually white mushrooms grew alone, sometimes by twos. Once all the neighboring bushes were examined, we headed for another mark in grandad’s map. Walking in a birch grove in central Russia was one thing, and climbing mountains, overgrown with wild trees and thorns, was another thing. In Russia, there were grannies, aunties, my younger sister Katya (a diminutive form of the name Catherine) who needed to be watched all the time, but here, in Georgia, we did not take younger sisters with us but, instead, took a map and marine binoculars – and that was already a real adventure. When the sun was straight above our heads, we would stop for a rest in the shade of a big oak near the noisy mountain river, and grandad would take out a one-liter bottle of young wine, cheese, tomatoes and fresh lavash (thin, flat bread which is often unleavened) from the basket. After dinner he had a rest under the tree, while I went for a swim. The water was icy-cold, so it took my breath away. But how amazing it was then to lie down on a large hot stone amid the turbulent stream, to listen to the babbling water and to admire small rainbow trout and quick-moving river crabs!

If the basket was full, grandad tied the shirtsleeves together, making a decent sack where we could put white mushrooms. As we approached our house, granny Tamara waved her hand to us and laughed: “Grandfather is returning in the T-shirt again! So you have gathered many mushrooms again!”

Sometimes grandad woke me up early and took me to the garden. He used to awaken at 5 in the morning himself, but woke me up at about 7. “We have two plum trees with tasty fruit in the edge of the garden. Let us go and gather them!” Usually I saw plums only in autumn, when my mother used to bring them in a packet from the market where they were sold at a high price. I gladly took the basket and dashed headlong into the garden. Oh, to gather plums! I had no idea that plums grew not only on bushes, but also on trees! The trees were big, with thick, knotty branches, entirely blue because of plums. The plums had a honey taste, and for the first five minutes I ate them non-stop and desired to stay under that tree forever. But by the evening I used to sit, exhausted by weariness and heat, and looking at rows of baskets, I used to think: “I am sick and tired of them!” Then these plums were laid out in the terrace to get dried later turning into the tastiest prunes in the world, and my granny made from the rest of the fruit wonderful cherry plum sauce (tkemali sauce) in a large cast-iron cauldron.

Everybody in the neighborhood had large gardens. Once I and some other boys made a raid on one of them. And do not ask why: that was the custom! First you play football and scouts, climb mountains and bathe in the mountain river with its chilly water, and after that you take the nearest fortress or somebody else’s garden by storm. Of course, that is if you are a true dzhigit (a brave person, a bold fellow), rather than a milksop who is tied to his grandmother’s apron strings. A real man always climbs to the very top of a huge old apple tree at which one was even afraid to look. When grandpa Vano, the garden’s owner, appeared, all the boys ran away and I remained alone on the top. Grandpa Vano cries from below in Georgian: “You are a complete fool, aren’t you?” And I reply from the top in Russian: “Grandfather Vano, I am sorry, I do not understand in Georgian!” I get down from the apple tree and, looking aside, begin to explain that my name is Beso, I come from Russia and now am visiting my grandfather Misha and grandmother Tamara. As he listens he begins to smile: “Oh, Besiki (a diminutive form of the name Beso)! You have grown into such a big and strong guy! Do you remember me holding you in my arms when you were tiny?”

He kisses me, pats my cheek and laughs into his beard. Then he takes a big woven basket from the shed and leads me where the hugest and tastiest fruit grow. He picks sunny, fuzzy peaches, purple ripe figs, fragrant pears and grapes. When the basket is full, he takes me home, calls grandmother Mariko and, while she is fondling me like a first grader, goes away and then returns with a large bottle of wine. And this is from grandfather Vano to grandfather Misha!

And thus the unlucky Robin Hood comes back home with a huge basket of fruit and a bottle of wine. My grandmother spreads her arms in amazement, but as she can only communicate with her Russian grandson by means of signs and smile, she is unable to learn the truth. Hearing the noise, my cousin Tina (who already knows everything from somebody) comes running and starts quickly giggling and gabbling, something particular to younger sisters. Unlike grandmother, Tina speaks Russian perfectly and at once starts imitating an adult. She folds her hands on her chest, and making her eyes big and round, asks with a strict voice: “Besiki, why have you stolen into grandfather Vano’s garden? Were your own fruit not sufficient for you?” I have an unbearable desire to pull her pigtail, but instead I sit with an imperturbable and proud look on my face and keep silent. A real man can either win or lose. There is no alternative. You have fought today, but you have lost, and you have only to die as a hero… Or to get grandfather’s strap as a punishment – but that was the same.

But grandfather Misha never scolded his grandson. He trusted me. And he resolved the problems of upbringing much better than very experienced educators and psychologists. Grandpa quietly listened to my granny’s lamentations, shaking his head, and then called me: “Boy! Your father and you were going to the stadium on the weekend (that was a match between the Moscow’s Spartak and Tbilisi’s Dynamo). But it appears that you enjoy climbing someone else’s apple trees more than watching big football, so I will ask him not to take you there until a breeze blowing through your upper story calms down.” One should have seen my face in that moment! The day before I had shown grandfather the championship times and the tickets bought by my father for the match. The best seats, by the way…

When I realized the meaning of grandfather’s words, the sky fell to earth for me, and all the horror of my misdeed arose in my mind. It was no use crying – it got even worse. But I remembered that life lesson forever. And grandad, as if nothing had happened, poured out goldish seven-year-old wine from the barrel for grandfather Vano, then proceeded to the apiary for incredibly fragrant honey for grandmother Mariko and sent me to them with our gifts in return. He was wise and generous, my Georgian grandfather Misha.

Granddad wanted me, his first grandchild, to become a real man, and insisted that I engage in sports from childhood, as had been earlier the case with my father. My granny would shake her head: she wanted me to study at a musical school and become a famous pianist. Even an old German piano was bought for me on which I played school sonnets and the Flea Waltz (called Dog’s Waltz in Russia). Soon a compromise was found: I was allowed to give up piano a year later when I won the second place prize at the city judo competitions.

My first Tbilisi friends were Slavka (a diminutive form of the name Vyacheslav), Andrei and Zhenka (a diminutive form of the name Eugene). Slavka was Belarusian; Andrei was Russian – his ancestors, Cossacks, once lived in Crimea and later moved here; and Zhenka was Armenian and his name was pronounced ‘Jan’ in his native language. But for us he was Zhenka—the best football player and the main ringleader in our mischief. His father was director of a big clothes factory and he made Zhenka wear ironed trousers and clean shirts. The latter much suffered from this and often tore them in “battles” and on high fences. Instead of listening to Zhenka’s rational explanations that creases on trousers are not that important in war, his father threaded a needle and compelled him to sew up holes in his trousers.

All the boys were aware that the main thing in war was to stand for the motherland and for the truth. This is what our grandfathers, war veterans, taught us, and this is what we read in our favorite books. How could we naïve boys have known that the democracy and freedom that swept over the former USSR like a tsunami would turn out to be a frivolous and fickle lady, constantly changing her favorites and always claiming her rights?

Democracy won in Georgia several times before my very eyes. Once during my holidays it won under one banner, and another time under other banner. In the first case, after the first democratic President Zviad Gamsakhurdia (who was later declared a “dog”) the Kremlin’s turncoat Eduard Shevardnadze came to power. He betrayed his comrades from the Central Committee and doomed the country to anarchy and utter poverty. Under this ex-minister of foreign affairs of USSR, the plunder of one of the most prosperous republics of the Soviet Union was organized on a national level: Georgian industries were transferred to Turkey, mafiosi served as ministers, and in Tbilisi (which formerly never even had disco clubs because they were considered immoral) drug sales in streets became common. Every time I would come to visit them, my relatives, woozy from television, used to tell me about their victory over the wicked Russian empire, the friendship with an American marshal, the imminent “golden rain” from the West and new, unbelievable opportunities. Among those who said these things were my uncle, a well-known restorer who had graduated from Volgograd University, another uncle whose business flourished in Tyumen (a Russian port town on the Tura River), my aunt—a historian, and my own father who had met my Russian mother in Yekaterinburg where they had studied together.

At that time, shops all over Russia stood empty and everywhere besides Moscow were food cards. Here, in Georgia, shop shelves were overladen with abundant goods, portraits of Stalin hung everywhere, and my accounts were interpreted as inventions and Kremlin propaganda. With one voice all spoke about the best wine in the world, the tastiest Georgian tea, and marvelous mandarins on which the country’s economy would grow and develop rapidly. Russia was still unaware that it was a “terrible and blood-thirsty empire” and continued to export petroleum, gas and electricity to Georgia for extremely low prices until it was shown the door point-blank.

Soon democracy won in Georgia with the Revolution of Roses, when the uninvited son of Georgia with an American passport, Mikheil Saakashvili, assumed power, and men in jeeps began shooting down people right in Tbilisi streets. When I asked my relatives questions about Shevardnadze, they waved their hands at me and spat. Lights in Tbilisi were turned on only in the mornings and evenings, generators worked loudly on people’s balconies, and sellers on Shota Rustaveli Avenue sold firewood instead of roses. With my poor knowledge of Georgian I was not allowed to walk along Tbilisi streets alone in the evenings. My fellow-townsman, colonel Ilia Konstantinovich Novozhilov, who graduated from the famous Tbilisi High Artillery Command College with honors (most of the commanders of today’s Georgian army are its alumni), told me that his neighbors, with whom he had grown up together, first stopped communicating with him and then called him “a Russian invader.” All of my childhood friends had left Tbilisi by that time as well. As my father told me, they left for their motherland. “What are you talking about? It is here that their grandfathers lived and it is here that they were born themselves. This is their motherland!” I replied, perplexed. He would fondly stroke my head and repeat again and again: “My boy is quite silly!”

At that time I studied at Tyumen State University with my best friend, a Georgian, Georgy Khizhnyakov, who was to become head coach of the Russia national karate team. He came up to me after entrance examinations and asked: “Are you Beso Akhalashvili? I am Georgian too. Let us be friends!” There were two girls from Tbilisi in our course (excellent students, by the way), and their elder sister studied at History Department. At a restaurant owned by my friend’s uncle in the center of Tyumen, our numerous relatives and acquaintances as they drank good wine were with one voice telling silly students about the democratic, prosperous Georgia (which they, however, were admiring from the depths of the “cruel and bloody empire”).

Sometimes Georgian people, indeed, behave like children. Children cannot love “partially”—they always love with their whole heart. These kind of people are loved by God and hated by enemies. Georgians are simply too sincere and openhearted to be good politicians. When I learned to read, my grandmother gave me three books: Georgian Folk Tales (from which you can study Orthodoxy like a catechesis); the novel Besiki, dedicated to the prominent Georgian poet and political figure Besarion Gabashvili (his pen-name was Besiki; 1750-1791) who made peace with Russia “forever” and after whom I was named; and the Lives of the Georgian Saints by Mikhail Sabinin. They were “bad politicians”, these great Georgian saints who fought against Genghis Khan and Tamerlane, the Turks and the Ottoman Empire. Also a “bad politician” was the Holy Martyr Archil II, King of Georgia, who chose to die for Christ instead of bowing down before the Ottoman invaders. These were also the Holy martyred Princes David and Constantine of Argveti; Ketevan the Martyr, Queen of Kakheti; the Holy Martyr Shushanika (or Susanna), Queen of Rhan; the Holy and Right-Believing Luarsab the Martyr, King of Kartli; the Holy Prince-Martyr Bidzina Cholokashvili; the Holy Princes and Martyrs Elizbar and Shalva of Ksani; St. Constantine, Prince and Martyr; the Holy Martyr Shalva, military commander and Prince of Akhaltsikhe.

These were tsars and princes who preferred suffering and martyrdom for Christ to the “well-fed” prosperous life of a traitor. From childhood they dedicated their own lives and their offspring’s lives to the Savior. It is hard for modern people to understand this: how can one reject a royal throne, power and wealth for the sake of some religious convictions? But Georgia, its mentality and culture, are founded precisely on these religious convictions and it cannot be understood without them.

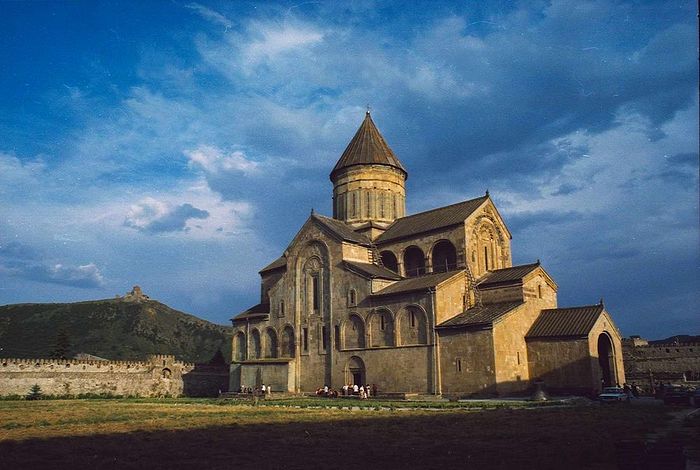

My parents were married in the principal church of the country—at Svetitskhoveli Cathedral where all Georgian kings had been anointed. That was back in 1972 when people in the Soviet Union spoke about religion only at “scientific atheism” lectures. Despite the official Communist ideology, the traditions of Orthodoxy were always kept in old Georgian families. All my Georgian grandparents, uncles and aunts, brothers and sisters were baptized in infancy. How a can Georgian not be Orthodox? Would he be a true Georgian? One should see how Georgian people love and honor priests! When my father went to visit my younger brother Mishiko’s schoolteacher he slaughtered a ram, but when he went to visit a priest he slaughtered two. I still recall conversations at our family table on Old New Year (January 14, the New Year according to the old calendar, widely celebrated in Georgia, Russia and some other countries) which I first celebrated in Tbilisi. “We bought our priest a new car!” “Good for you! And we are building our priest a new house!” A Georgian priest knows all parishioners until the seventh generation and he is always very welcome and cordially received by any household. A priest in Georgia is a much higher authority than any distinguished politician. Some like political figures, some do not, but clergy are loved by all!

Once I read in a newspaper a story about one compassionate billionaire from abroad. He was dining in an extremely expensive restaurant when a poor old woman accidentally entered it. A glass of plain water there was more expensive than her entire pension for a period of ten years, so the old woman was shown the door. When the billionaire saw what was happening, he became indignant, ordered to let all the customers go, to seat the poor woman at the table and offer any food that she would choose. The readers should have been touched and moved by the generosity of that man, but in Georgia any man would have been ashamed of being mentioned in such an article. “What greed—he only gave her food!” a Georgian would say. “He should have paid for her treatment at a top-class hospital, hired her nurses for the rest of her life and built her a new house! Can a real man be proud of this story?!” My father, a hard worker, could easily give all his money to any stranger in trouble and then go without food together with his young wife until the following salary. After that he would be scolded, shamed, persuaded, even become horrified by his own deeds and imminent penury, each time promising to change his ways. But he would do the same thing again and again, explaining it thus: “You see, their house burned down (their cow died, their child could not be admitted to a hospital).” Knowing that he was always willing to help and unable to say no, some people often used his gullibility and openly deceived him. When it turned out that the house had not been on fire, the cow was alive, and the child even did not exist, he only sighed and spread his arms, but he could not do it a different way.

In order to take his wife to the best city restaurant, father unloaded cargo from freight cars and moonlighted on building sites. And whenever they came into a restaurant he would put a bottle of champagne and white roses on each table, and only at the table where he dined with my mother, surrounded by musicians, the roses were always red. He could also buy a whole hand cart of Eskimo ice-creams [chocolate ice cream on a stick which was very popular in USSR] sold by street traders and then roll it in the park before my mother, distributing it among passers-by shouting loudly, deliberately mangling the Russian words: “Eskimo ice-cream, Eskimo ice-cream!” If he had no money at all, he could pull up an apple tree from the ground and bring it to my mother, or recite poems by heart at her window all night long. Mother used to say that he had a perfect memory and could memorize any text verbatim at the first reading! When mother was preparing for her exams, father learned all the examination papers for her and then checked them.

I recall how once my father and I were driving from Tbilisi along a very beautiful and narrow road that winded amid sheer drops in the mountains. Ahead of us, on a tiny patch under a rock, was an ancient little Chapel of the Mother of God, covered in moss. My dad left the car on the road (there was nowhere else to leave it anyway) and we both went there. While we were in the chapel, several cars gathered on the road behind ours. Some drivers decided to get out and venerate the shrine as well, while others were waiting patiently. When we came back, we did not hear a single word of resentment, anger or murmuring: only smiles and understanding looks. A man must not be disturbed when he is communicating with God…