Reading discussions about life after death, it is easy to get the impression that people actually know what they’re talking about, that perhaps they have been there, seen what goes on and therefore authoritatively opine on the nature of things. But, the truth is that we mostly don’t know. We have a few things given to us in Scripture, and even those few things are often somewhat cryptic or uncertain. I will come to what we may say with certainty later. But here at the beginning of this article, I want to say that we don’t know much.

As an Orthodox believer, I am comfortable with not knowing much. Strangely, Orthodoxy has a whole spiritual lifestyle based on not knowing much—it’s called apophaticism. But why do so many seem to (or claim to) know so many details—and to know them so well that they gladly enter into arguments on the topic? To a great degree, the answer is simple: arguments.

The greatest and longest argument in Christianity has raged between Protestants and Catholics for 500 years. Some might want to say that the split between the Orthodox and the Catholics is a longer argument. But though that split is 1,000 years old, it has not mostly been an argument. If anything, it has mostly been a case of not talking to each other. However, the rise of Protestantism must be seen as the rise of an argument. It began specifically as a critique of Roman Catholicism. One of the primary critiques of Catholicism centered around details of life after death. The notion of purgatory, the merits of the saints, heaven and hell, prayers for the dead, all came under fire in one way or another from virtually every angle of Protestantism. And Catholicism responded, particularly in the Counter-Reformation.

Arguments can have a life of their own. One aspect of an implacable target in an argument is the near impossibility of agreeing with them or ceding any ground whatsoever. Lines of thought become refined and ossified. I have an easy summary of Protestant thought about life after death: “Catholics are wrong.” Protestant thought on the afterlife is streamlined. Its scheme of salvation, of reward and punishment, is very straightforward and without wrinkles. Catholic thought, particularly as developed in response to Protestant critique, is not so straightforward, but it developed a very clear shape with definitive contours and describable rules.

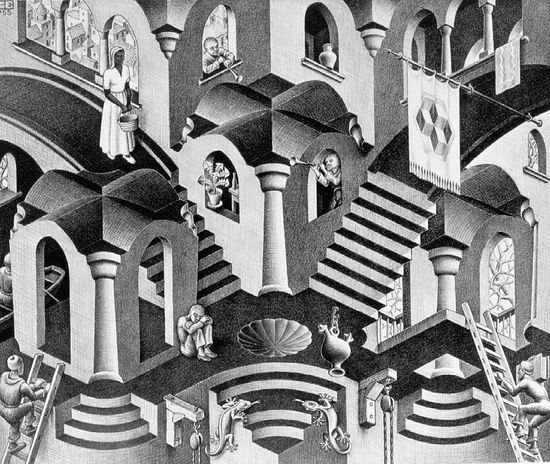

Orthodoxy, on the other hand, seems sloppy, even murky. Why do the Orthodox pray for the dead? “Because it is of benefit,” comes the official answer. Exactly how it benefits is a field for speculation and theologizing, but not a field for dogma. There are interesting details, rooted in what is essentially folklore, such as the “toll houses,” a description of particular judgments and battles with demons confronting the soul on its way to heaven (if it makes it). Stories abound in Orthodoxy. A saint prays and frees a soul from hell (it’s not an uncommon story). However, there’s no explanation for how such a thing can happen. Once a year, at the Vespers of Pentecost Sunday, prayers are offered for all the souls in Hades from Adam to the present. Again, no explanation is offered. Is Adam still there? Christ is seen in the icon of the resurrection taking Adam by the hand and leading him out. But there are the prayers.

It is deeply tempting (and frequently not resisted in the least) for Orthodox Christians to seek to systematize the whole process. This offers the convenience of making arguments with Catholics and Protestants more interesting. Saying, “We don’t exactly know,” is simply not persuasive. What apparently disturbs many Christians is the notion that we don’t actually know a lot about what seems an important matter (where I’m going to go when I die, what it’s like, how do I get there, etc.). But that is the plain truth. We don’t really know very much.

But we do know certain things, and they are the things that matter. When I say we “know,” I mean that as a solid data of the received faith, the very core of Christianity, we “know” or have been given to “know” certain things. We know that Christ died and was buried. We know that He rose on the third day. We know that He “trampled down death by death,” He “led captivity captive.” The way to the resurrection has been opened by Christ. We know that if we are Baptized into His death, we shall also be raised in the likeness of His resurrection. And these are, generally, the sorts of things we know and can say for certain.

We are nowhere in the Scriptures, nor in the Tradition, given a roadmap complete with rules for life after death. Some like to make up rules because it makes a form of preaching sound plausible: “Unless you accept Christ as Savior, you’ll go to hell.” But, such preaching is largely based not on the Scriptures, but on the roadmaps of certainty forged in the debates of the Reformation. The Christian gospel is not based on accurate knowledge of the roadmap. The gospel is based on the certainty of Christ’s resurrection from the dead, and the promise that His resurrection is the sure and certain hope of all of creation to be delivered from its bondage.

The life and practices of the Church are built around this sure and certain hope. However, our hope and our certainty are not based on a topographical tour of the afterlife. Of course, it is impossible to suggest that people not ask questions or wonder about the topic. And the Church’s life is filled with stories and practices (such as prayers for the departed) that are rightly part of the ethos of the faith. But we do well to speak the truth to ourselves and accept the humility that God seems to have assigned to this topic.

It is important, as well, to resist the pressures that come from arguments of modern Christianity. The feeling that we are supposed to have assurance or certainty about the details and mechanics of all this is not a part of the Tradition, but simply an artifact of the argumentative habits of the past 500 years. Christ did not come to reveal the metaphysics of life after death. He came to destroy death. Having done so, those who follow Him seem strangely drawn towards the creation of a new paganism in which the afterlife is central. The truth is that union with Christ, in His death and resurrection, are the only central things in our faith.

At every turn, the source of our hope is simply what we have seen accomplished in Christ. We have His promises: I go to prepare a place for you, and if I prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you to Myself; that where I am, there you may be also. (Joh 14:3) The fullness of the life of the Church teaches us how to hope and how to pray. It does not teach us what has not been given us to know.

I’ll close with a speculation of my own. I strongly suspect that one of the reasons we do not really know much is simply the nature of what there is that we want to know. Every version and image of life after death is inevitably nothing more than a beefed-up version of something we already know. But if, as St. Paul says, Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor have entered into the heart of man the things which God has prepared for those who love Him, (1Co 2:9) then we might simply not know because it is beyond our knowing. It is also not unlikely that such knowledge would be a distraction—that is already evident by our wholesale abuse of our ignorance.

We know Christ, crucified and risen. He is our Pascha. Know that.

St. Ignatius Brianchaninov himself discovered, while researching such topics -- the life of the soul after death, angels, demons, etc that the Church is quite precise on such matters, and it's the increasing influence of philosophy and dependence on worldly things that cause us to lose our understanding.

Why Fr. Stephen feels the need to submerge Church teaching into vague obscurity is hard to grasp. Or to relegate the millennias-old consistent teaching of the toll houses to the realm of "folklore" ... his article is unfortunately rather poor, and unfortunately, that is not so uncommon with him.