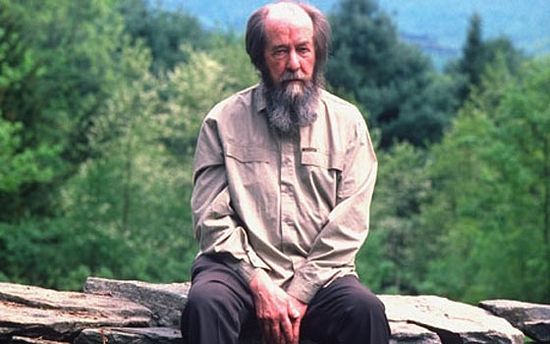

For a variety of reasons, I have been spending a fair amount of time with A.I. Solzhenitsyn, the great Russian writer who died in 2008. I am working through a collection of his writings and have been watching videos on his life along with detailed interviews. If any man lived through the maelstrom of the 20th century, it was he. Born in 1918 to a pious, Orthodox family, he was raised by a single mother, his father having died in an accident six months before Solzhenitsyn’s birth. Moving to Rostov when he was 6, Solzhenitsyn gradually became an enthusiastic Soviet boy. He learned to hold his faith in disdain and admire the Revolution. He even became a member of the Young Pioneers.

Like Dostoevsky before him, Solzhenitsyn was something of an idealist in his youth. His Marxism was quite real. Towards the end of World War II, in which he served with honor, he was arrested for remarks critical of Stalin in some of his private correspondence with a friend. Interestingly, his remarks were to the effect that the State was deviating from a proper Marxist course. His indiscretion made a prisoner out of him in the Soviet Gulag.

His first imprisonment was relatively easy, eventually being assigned to a sharashka, doing mathematical and engineering research. His acquaintance with older men with greater experience and a far more critical approach to the world began to move him back towards his childhood Christianity. He was removed from the sharashka and sent to one of the hard labor camps in Kazakhstan, and then sentenced to internal exile (for life) working as a teacher of mathematics.

He was rehabilitated in 1956 during the early Krushchev years, during which his first work, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a graphic novel set in the Gulag, was published. It sold extremely well and brought him into the public attention that would remain with him, both as a writer, and as a social critic, for the rest of his life.

He is more compelling to me than any other man of our time, in large part because of the simplicity of his soul. There is a Russian phrase, “dvoye dusha,” (literally “two-souled”) that comes to mind. Most people that I know are at least “two-souled.” Our complexity is a mass of contradictions – in opinions, sentiments, loyalties and loathings. We think one thing for one reason, and something else for a completely contradictory reason. It is one of the diseases of our age (cf. Alasdair MacIntyre’s Whose Justice? Which Rationality?) Solzhenitsyn was decidedly not dvoye dusha. He was utterly what he was to the very core of his being. Were it not so, he would have learned to bend and give way, and get along in the world. He could have been quite “successful” with a lot less trouble.

This inner simplicity is all the more remarkable in that Solzhenitsyn lived in extremely complex times. The State that imprisoned him was once idealized by him. And the State that oppressed him and sought to silence him was also located in the land that held one of the deepest places in his heart. He was exiled in 1974, eventually settling in Vermont. Hailed across the world as a champion of freedom, he nevertheless found that the Western media turned on him when he offered criticisms of the abuse of freedom and the rampant decay of life in the land of his exile.

In time, the media found it easier to dismiss him as a Russian curmudgeon, an artifact of a society that had long past. He was accused of many things (much as his Soviet masters sought to discredit him). But the truth of the man was that he was utterly the same, whether living under the Soviets or being hailed or lampooned in the West. That both East and West were glad to see him silent is simple testimony of the almost unlimited corruption of the modern state.

His practice of life can be summed up in the title of one of his articles: “Live Not by Lies.” The article itself is worth a read. For Solzhenitsyn it meant (at the very least), speaking the truth of his heart, always and at all times, without fear. And this is where the problem of being “two-souled” comes to the fore. There are terrible forces that draw us away from the simple truth of our soul. The audience itself, our passions, and such things easily create a cloud of confusion.

Thinking about this is quite painful for me. For a number of years, prior to my conversion to Orthodoxy, I lived a very two-souled existence. As I was increasingly drawn towards Orthodoxy, I was also repulsed by the Anglicanism in which I served. The complex levels of employment, parenting, serving, and the like created terrible contradictions within me. If every day did not involve direct lying, it certainly involved something very close to it.

About a year before my conversion, I went to my Anglican bishop and told him of my intentions. It was a very irenic and thoughtful conversation. Towards the end he asked me, “Can you say mass in good conscience?” It was probably the most poignant question of the morning. I told him that I could, though it was something of a circus act in my soul (I used a different expression that I’ll not repeat). He told me to let him know if it became unbearable.

My eventual conversion at the beginning of the next year came as a deep relief. I felt no triumphalism in the act. Indeed, I carried deep wounds as a result of the “dvoye dusha” that held me over the course of a number of years. It still haunts my dreams.

My situation is a rather dramatic example (and embarrassing). But the problem is, I think, very widespread in our culture. We carry a host of contradictions within ourselves. The passions, devoid of reason, frequently dictate both the attachments of our lives and how we treat them moment by moment. A single and simple heart are rare and difficult to achieve.

Christ said, “Let you eye be single.” He also said, “Let your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes’ and your ‘No’ be ‘No.’ For whatever is more than these is from the evil one.” (Mat 5:37) St. James says that a “double-minded” (literally, “two-souled”) person is “unstable in all his ways.” For many, this has become their mode of existence.

A single and simple soul comes through a certain stillness of mind and purpose and a singularity of devotion. There can be little doubt that Solzhenitsyn’s simplicity was partly shaped by the suffering he endured. It was also shaped by the simple and straightforward nature of his Orthodox faith. It is only remarkable because it is rare, but not because it is difficult to achieve. Solzhenitsyn’s own advice was, “Do not lie.”

Lying pervades our lives. I often think we are so engaged with lying that we fail to notice. The lying begins within our own hearts. What we experience as “complexity,” particularly complexity within the soul, is often little more than a refusal to face the truth and endure its consequences. We prefer a life in which unpleasant consequences are minimized. Lying is ideal for such a life.

The gospel begins with a call to repentance. Repentance (metanoia), means a “change of mind.” It is not just changing the thoughts of the mind, but changing how the mind thinks. St. Paul speaks of the “renewing” of the mind (Romans 12:2). Christ’s calling of the disciples is a perfect example of this renewing. Christ seems to have made any double-minded following impossible. Men leave families, jobs, everything that has constituted their lives prior to Christ. He counsels them to “let the dead bury the dead.” These actions have always seemed extreme, but as years go by, I see that they have this aim of concentrating the soul.

Our entrance into Christ (and into the fullness of the Church) rarely asks such efforts on our part. At the time of my conversion to Orthodoxy, I was actually grateful that my circumstances were radically affected, even if most of the effects turned out to be products of my own anxious mind. There was nothing truly heroic, or that involved any noted suffering, but in an age of comfort, where we fear every inconvenience and the loss of any security, there was sufficient difficulty to begin the process of healing my conflicted soul.

In every life, that process can begin at any time. It starts with a resolute commitment to follow Christ, regardless of consequence. We are asked in Baptism, “Do you unite yourself to Christ?” This, it seems to me, is so much more than simply “making a decision for Christ,” or “accepting Him as Lord and Savior.” It is asking us to die. For the Christ to whom we unite ourselves is, first and foremost, the Crucified Lord. “I die daily,” St. Paul said. Nothing less than that heals the heart.

For the first two years of my Orthodox life, I worked as a hospice chaplain. As I worked at “dying daily,” I was daily with the dying. The approach of death, in the life of a believer, properly concentrates the soul. It was a great benefit to me to bear witness to those witnesses of a single heart. Three years ago I was in hospital with a heart attack, watching the medical staff scurry about the business of saving my life. In the middle of it all, there was a great peace. There was only one anxiety – that of meeting Christ unprepared. I turned down the offer of a sedative as the procedure began. “I have work to do,” was my comment.

I have no judgment for any who wrestle with a divided soul. But I can say that it is not a state that we should tolerate for long – it is too devastating. There are truly great souls, singular points of grace that tell us of what is possible. Solzhenitsyn became a hero for me, even within my college years. I suspect the disease of my own soul intuitively saw in him the example of the way home. Yes or no. Do not live by lies.