A stained glass image of St. Edith at Polesworth abbey church (taken from Warwickshirechurches.weebly.com)

A stained glass image of St. Edith at Polesworth abbey church (taken from Warwickshirechurches.weebly.com) Unfortunately, there is no reliable information on this saint’s ties of kinship (that would make her different from other female saints of royal blood). Thus, according to a tradition recorded in the twelfth century at Bury St. Edmunds and later recounted by the famous chronicler Matthew Paris (c.1199-1259), St. Edith was a sister of Athelstan (895-939) who effectively became the first ruler of all England. If that is true, then her father was King Edward the Elder (c.870-924), King of Wessex and son of the saintly King Alfred the Great. Another source, the historian William of Malmesbury, early in the twelfth century, confidently wrote of this saint as “daughter of King Edward the Elder and his wife Ecgwynna”. If this was so, then she was truly a sister of King Athelstan, but William refers to no sources confirming that one of King Edward’s daughters was called Edith (it should be said that the period of reign of Edward the Elder and Athelstan is very sparsely covered by written sources).

The Bury St. Edmunds tradition goes on to relate that in 925 in the city of York, King Athelstan gave his sister Edith in marriage to the Danish king of South Northumbria named Sitric Caech (Northumbria was then a part of the Danelaw—the territories in the north and east of England in which Danish laws and customs were observed from the late ninth century until the Norman Conquest). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions the same event, but under the year 926 rather than 925, and it does not provide the name of the King’s sister. According to other and less genuine traditions, St. Edith was a sister of the Holy Right-Believing King Edgar the Peaceful and so the aunt of St. Edith of Wilton—in this case she must have lived at least twenty years later and could not have married Sitric.

A medieval effigy believed to be that of St. Edith at Polesworth abbey church (taken from Warwickshirechurches.weebly.com)

A medieval effigy believed to be that of St. Edith at Polesworth abbey church (taken from Warwickshirechurches.weebly.com)

The veneration of St. Edith in both Polesworth and Tamworth continued for many centuries. The history of Polesworth village and its convent is interesting. In the Anglo-Saxon period it was a tiny village in the kingdom of Mercia. Founded in the seventh century in the valley of the River Trent, Mercia grew into the largest early English kingdom and the most influential after Wessex. It gained a special importance under King Offa (ruled 757-796), but after his death, Mercia was invaded by King Egbert of Wessex (d. 839) in 825 and supremacy gradually passed to Wessex. According to a legend, once Egbert and his army were in an area of Mercia where they could not find a spring or water basin. They sent a scout who found a small river called the Anker near the wood on which bank the village Polesworth lay. Thanking God for His mercy, Egbert vowed to build a monastery in this area. Though this place already had a small community of nuns in honor of the Mother of God, by that time it was probably in decline. Egbert’s son called Aethelwulf rebuilt the nunnery whose main church stood on the site of the north aisle of the present church. As the convent was situated in the depths of the Forest of Arden, its timber was used for building. During the pagan Viking raids on England, when many monastic sites fell victim to the Danes, Polesworth Convent remained unscathed together with the village due to its location in the forest. Monastic life at Polesworth prospered for many years until the bloody Reformation. In 1090-1139 the convent was rebuilt and considerably enlarged. The new stone convent comprised the main church (part of which survives to this day), a gatehouse (also survives to this day), the dwellings for nuns, an infirmary for the sick, a smithy and a bakery. A school was attached to the convent that received many pupils, including members of noble families. This school was known not only in England, but in continental Europe as well; it was called “The English School”. The convent possessed large gardens in which nuns grew vegetables and medicinal plants. The nunnery also had watermills which were even used by the local villagers. For many years nuns bred fish in the fishponds. Life at Polesworth continued the traditions which had been practiced under the Holy Abbess Edith: the nuns clothed and fed the poor, gave them alms, cured the sick, accommodated travelers, gave lodging to strangers, cared for all those who sought their aid and cordially received guests, both rich and poor.

There were many cases of miracles in this church through the prayers of St. Edith, along with cases of her posthumous apparitions. For example, in the first half of the twelfth century, Sir Robert Marmion, a local magnate who was grabbing the lands of Warwickshire, once expelled the nuns from Polesworth to Oldbury several miles away, and thus Polesworth Convent was briefly deserted. Soon after that, when Robert was sleeping in his bed after a lavish party, St. Edith appeared before him, hit him with the edge of her staff in his side and strictly (though she had been very meek) ordered him to return the sisters to Polesworth and warned him that if he refused he would die a wicked death. Frightened, Robert at once allowed the nuns to come back to Polesworth.

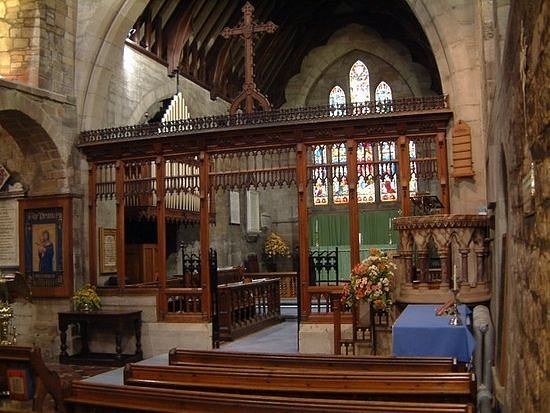

In 1537, under Henry VIII, when nearly all English monasteries were closed, representatives of the king came to Polesworth Convent, in which at that time some 38 nuns lived and between 30 and 40 children studied. It was then decided not to dissolve this community, “otherwise the life of this village and all neighboring settlements will decline”. However, in 1539 Thomas Cromwell sealed the fate of this ancient holy site (in spite of 50 pounds being paid by the community) and monastic life in Polesworth ceased forever. In 1544 most of the monastic buildings were demolished. The Abbey Church of St. Edith continued to exist only as a parish church. This beautiful church stands there to this day, though it is considerably smaller than it was before the Reformation. The church is mainly from the twelfth century with some later additions, and is beautifully decorated inside. Among its treasures is a medieval (thirteenth-century) effigy of an abbess believed by many to be St. Edith herself, which lies on an old tomb chest1 in the nave. The figure holds an abbess’ staff and a book. In the Middle Ages, crowds of pilgrims came to venerate this effigy which was said to possess healing properties. The patron-saint of this church is also commemorated here in lovely stained glass. The gatehouse of the former abbey along with the refectory and the cloisters were recently restored; archaeological research on this site was initiated not long ago; bodies of medieval nuns were discovered along with other artefacts. Minor ruins of the former abbey surround the church, and the site preserves the spirit of holiness and peace. Pilgrimages to Polesworth have resumed, and it is considered to be the greatest ancient former monastic site still in existence in Warwickshire.

Polesworth is not only famous for its monastery. After the dissolution, the lands of the abbey were purchased by the noble Goodere family, one of whose members, Henry Goodere (1534-1595)—a patron of arts and culture—built a manor called Polesworth Hall, which gathered many representatives of creative circles of the Elizabethan age. Thus this place was closely associated with such figures as the poet Michael Drayton (1563-1631), the dramatists William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Ben Jonson (1572-1637), poet and clergyman John Donne (1572-1631) and the architect Inigo Jones (1573-1652). The history of St. Edith’s Church in Tamworth, Staffordshire, is also very interesting. Guidebooks refer to it as to the largest medieval church building in the county. Most of the current church is from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It stands on the site of the original church that stood here as early as the eighth century. The first church was burned down together with the entire town by the pagan Danes in 874, and in the following century under Abbess Ethelfleda a new church was built on its site. But that edifice was also destroyed by the Danes in 943 during one of their raids. A generation later it was restored by St. Edgar the Peaceful. With time a portion of the relics of St. Edith of Polesworth was translated to this church, and the saint became its patron from that time on (the idea that in Tamworth there was another saint with the name Edith whose relics this church possessed is dismissed by many, but not by all, researchers).

In 1345 during a devastating fire the whole town of Tamworth fell into ruin, and the church of St. Editha was burned down as well. Immediately after that the building of the splendid church that stands here today began. The community of canons, which had been attached to this church before the Reformation, was dissolved in 1548, and the building has been used as a parish church since then. Among its treasures—numerous historic stained glass windows (depicting, among others, St. Edith) and an old eighteenth-century organ.

No fewer than 15 ancient churches in the Midland counties of England are dedicated to our saint, though a number of them bear the name of “St. Edith”, with no indication as to whom exactly they are dedicated, for there were two early Orthodox saints of England with this name: St. Edith of Polesworth and St. Edith of Wilton (Wiltshire). Apart from the churches in Polesworth and Tamworth mentioned above, there are the following churches that are worthwhile noting: the twelfth-century church of St. Edith of Polesworth in the village of Church Eaton in Staffordshire; the church of St. Edith of Polesworth in the village of Amington near Tamworth in Staffordshire; the church of St. Edith of Polesworth in the village of Monks Kirby in Warwickshire (this is a former priory church as it belonged to a Benedictine priory founded here after the Norman Conquest; the first church on this site was built by Ethelfleda, daughter of St. Alfred the Great); the church of St. Edith of Polesworth in the village of Orton-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire; the beautiful Norman church of St. Edith (either of St. Edith of Polesworth or of Wilton) in the village of Eaton-under-Heywood in Shropshire, renowned for its many stained glass windows, some of which were created by the Worcestershire architect and stained glass painter Frederick Preedy (1820-1898); the eleventh-century St. Edith’s church in North Reston near the town of Louth in Lincolnshire; St. Edith’s church in perpendicular Gothic in the village of Grimoldby near Louth in Lincolnshire; the ancient and pretty St. Edith’s church in Coates-by-Stow in Lincolnshire (there was trade between Tamworth and Coates in ancient times) and others.

Thus the memory of St. Edith, a daughter of an English king who devoted her life to ascetic labors for the Heavenly Kingdom and to acquire the grace of God, is preserved in England.

Holy Mother Edith, pray to God for us!