Source: Russia Beyond the Headlines

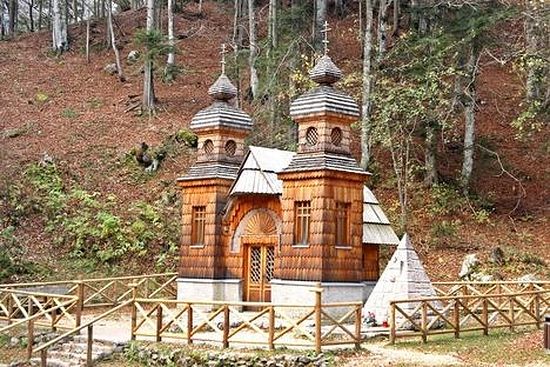

Around the small wooden chapel on the forested mountain slope in northern Slovenia, 3,800 feet above sea level, one hour’s drive from Slovenia’s capital, Ljubljana, and about 20 minutes’ drive from the Austrian and Italian borders, workers were busy building wooden plank platforms for VIP guests and decorating them with spruce branches.

On July 30, Russian President Vladimir Putin is expected here at the Vršič Pass for a high-profile visit to mark the 100th anniversary of a rather minor First World War episode, which stands nonetheless at the symbolic focal point of Russian–Slovenian relations.

In March 1916 more than 100 Russian POWs – part of more than 10,000 deployed here by the Austro-Hungarian command to build a mountain road – died in an avalanche. Their comrades built a Russian Orthodox chapel dedicated to St. Vladimir next to their graves – a memorial that several generations of local Roman Catholic Slovenes later preserved despite changing borders and political regimes.

With the emergence of independent Slovenia and Russia in the early 1990s, annual commemorations at the end of July, around the day of St. Vladimir, became the axis around which not only the humanitarian, but also political and economic relationship between the two countries developed.

The symbol at the heart of a relationship

The driving force behind the modern phase of the Vršič story, culminating with Putin’s visit, is Sasa Gerzina – Slovenia’s first ambassador to Russia in 1993-1995, who, since his return to Ljubljana, has led the Slovenia-Russia Society.

As his associates were sorting out the crates full of accreditation badges for the upcoming ceremonies – about 2500 people are to come to Vrsic on Saturday in 60 buses charted by the society – Gerzina told RBTH how he and his Russian diplomatic counterparts had struggled in the early 1990s with an unusual task: How to frame the relations between the two young countries?

All former Yugoslav states seemed to have something that tied them with Russia – either their Orthodox Christian background, or the history of Russian support for Serbia, or oil pipelines. “Here, in Slovenia, there was somehow nothing,” said Gerzina.

A solution suddenly came with the visit to Moscow of Sasa Slavec – a construction entrepreneur from northern Slovenia whose father had voluntarily assumed in the 1930s the maintenance of the Russian chapel and eventually passed on the duty to him.

“He said: ‘We have a Russian chapel, and it has been preserved by the local people for more than 80 years without any political or financial motives.’ Our Russian colleagues just did not believe it and said it was phenomenal,” recalled Gerzina.

Led by Sergei Glazyev, then minister of foreign economic relations and today President Putin’s adviser, the first Russian delegation came in 1993, with the late Bishop Sergei leading the Russian Church delegation. A number of businessmen were also present. According to Gerzina, those who attended were “thrilled” by the event, which “became a tradition.”

Later, when Slovenia refused to sign a friendship treaty with Russia, fearing it would have a negative impact on its course to join NATO and the EU, Gerzina convinced then Slovenian President Milan Kučan to attend the annual ceremony as a gesture of respect to Russia. That too became a tradition.

Politics, economics and spirituality

“During these years, we had the entire Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, coming one by one. In 2001 Metropolitan Kirill came, who is the Patriarch now,” Gerzina said. “It created such a framework of regular meetings, in which politics had respect for the civil initiative. And that rarely happens,” he concluded.

The tradition of Vršič commemorations has always compensated for the failures in other aspects of the Russian-Slovenian relationship. When the South Stream gas project fell through, Gerzina said, he convinced the governments of Russia and Slovenia to assume patronage over the three-year cycle leading to the centennial.

Russia's Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev laying a wreath by the Russian Orthodox chapel at the Vršič Pass. Source: Yekaterina Shtukina / TASS

Russia's Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev laying a wreath by the Russian Orthodox chapel at the Vršič Pass. Source: Yekaterina Shtukina / TASS As a result, in 2014, when after the annexation of Crimea the West attempted to isolate Russia, Slovenia was the only EU country to hold the regular intergovernmental commission meeting with Russia and in 2015 Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev came to participate in the Vršič ceremony.

“So,” said Gerzina, “I’d say Putin’s visit is not surprising. It is a logical continuation of what we’ve had to date.”