Monastic life in England fell into decline and nearly ceased to exist in the second half of the ninth century, due to the massive Danish raids on the English monastic communities. The saintly King Alfred the Great of Wessex and his sons Edward the Elder and Athelstan made some successful attempts to begin restoring monastic life in England, but a true revival of English Orthodox monasticism and piety became possible only in the second half of the tenth century, under the three saintly figures known as the “Three English Holy Hierarchs.” These were the holy hierarchs Dunstan of Canterbury, Oswald of Worcester and York, and Ethelwold (originally Aethelwold) of Winchester, three great archpastors for whom veneration was nationwide. Let us recall the life and achievements of St. Ethelwold:

The future saint was born to a wealthy family about the year 910 in Winchester, then the main city of Wessex and in effect the capital of England. Ethelwold's parents were lovers of the Church, who raised him in piety, and, from childhood, he desired to live a holy life. As a young man, Ethelwold served at the court of King Athelstan (who ruled from 924 to 939). All the while, he read voraciously and sought to gain as much knowledge as possible. About the year 939, he was ordained priest—on the same day as his friend St. Dunstan, by St. Alphege (Aelfheah) the Elder, also known as Alphege the Bald, Bishop of Winchester (+ 951, feast: March 12/25). About the year 940, the saint decided to join Dunstan at Glastonbury monastery in Somerset, where he was then tonsured a monk.

St. Dunstan was the leading figure in reviving monasticism in England under the rule of St. Benedict of Nursia, and Glastonbury, this very ancient holy site later connected by legend to St. Joseph of Arimathea (who reputedly had preached there in the first century), was to become the first monastery to be restored under that rule. St. Ethelwold energetically studied and taught at Glastonbury, prayed and fasted, labored diligently in obedience to his abbot Dunstan, became “a mirror of perfection,” and finally became the prior (abbot’s assistant).

It should be noted that, at that time, there were very few monks in the country; traditional monastic sites were occupied by married priests who served there and lived with their families nearby. St. Dunstan undertook monastic reform with great patience and prudence and did so very gradually throughout his life. He introduced monks to ancient holy monastic sites and trained them there, but allowed some married priests to stay and serve alongside, provided their life was one of discipline (by that time, discipline and Christian life were in decline across the country). However, very resolute, far-sighted, and quite stern by nature, St. Ethelwold was not satisfied with the situation at Glastonbury, which he considered to be too sparing and moderate. He personally longed for a more radical and rapid reform.

About the year 955, he resolved to leave Glastonbury and visit France in order to study the newly-reformed monastic life of Cluny. Meanwhile, both St. Dunstan and King Edred (who ruled from 946 to 955) did not want such a talented, vigorous, and holy monk to leave their country; his work was so dearly needed. So, Ethelwold was given the derelict and long-ruined monastery of Abingdon (the town’s official name is Abingdon-on-Thames) in Berkshire in southern England—now located in the south of the county of Oxfordshire. It is said that this ancient holy site was visited by the Equal-to-the-Apostles Empress Helen early in the fourth century, and she allegedly built a church there. Ever since, St. Helen has been considered the patroness of this town (considered to be the oldest continually-inhabited English settlement to date), along with the town of Colchester in Essex. The first monastery of the Mother of God was founded at Abingdon in the kingdom of Wessex, in the seventh century, but had been ravaged and destroyed by the Vikings, two centuries later. Thus, St. Ethelwold gladly agreed to move to Abingdon in 955, and, as abbot, restored it, taking some brethren from Glastonbury with him, along with clerics from elsewhere.

In many ways, Abingdon was restored on the pattern of Glastonbury, and it was the first English site outside Glastonbury in the tenth century where genuine and serious monastic life was revived. Ethelwold sent his close disciple Osgar to the monastery of Fleury-sur-Loire in France to study monastic rule there in his place. When Osgar returned and reported to him on the situation at Fleury, the saint introduced many elements from Fleury to organize monastic life in Abingdon and other monasteries (Osgar later became the second Abbot of Abingdon and it prospered under him). The holy man rebuilt Abingdon monastery in the form of a rotunda, partly using the materials from the former monastery, and beautified it. He also secured substantial donations and sizeable lands for Abingdon from royal figures. With time, Abingdon became famous for its strict monastic life, holiness, and education, all due to St. Ethelwold. His influence was so significant that the future holy King Edgar the Peaceful (+ 975, feast: July 8/21) studied at Abingdon in his youth and personally considered Ethelwold to be his spiritual father.

Among the disciples of St. Ethelwold at Abingdon was Saint Elstan (+ c. 981, feast: April 6/19), the future Abbot of Abingdon and Bishop of Ramsbury in Wiltshire. Ethelwold invited skilled singers from Corbie (France) to Abingdon to teach Gregorian chant, which was not yet common in England. When, in about 956, St. Dunstan was exiled for some while to Flanders by King Edwy (or Eadwig, ruling 955-957), St. Ethelwold became the most important churchman in English monastic reform, as well as a tutor to royal family members (thus, he personally signed and worked out a large number of documents and charters of King Edgar early in the 960s).

In 963, St. Ethelwold was consecrated Bishop of Winchester, which was one of the principal sees in the English land. As was reported, discipline in Winchester by the time of St. Ethelwold’s arrival was extremely poor. All priests were married, they knew the services poorly, they were illiterate, lazy, and gave themselves up to gluttony, drunkenness, and other vices. Perhaps this is a slight exaggeration, but it was reported that clerics truly did not wish to celebrate services regularly, although they promised St. Ethelwold daily to mend their ways. Finally, after one significant incident, the saint expelled all the married clerics from the cathedral and replaced them with his monks from Abingdon, thus starting a genuine monastic community there, and establishing the tradition of so-called “monastery-cathedrals”–a unique institution which existed only in England and continued until the Reformation.

Several priests expelled by Ethelwold soon repented and returned to live at Winchester as true monks. In that time, it was vital for the King to be a great patron, supporter, and benefactor of the monastic reform. The king’s palace was very near the main cathedral in Winchester. St. Ethelwold restored and revitalized life in all three “minsters” that existed in Winchester: the Old Minster for men (founded in about 648 for King Cenwalh of Wessex and St. Birinus), the New Minster for men (founded in 901, right after the death of St. Alfred the Great), and the Nunnaminster (a community for nuns founded in 903 by St. Elswith, widow of St. Alfred).

Milton Abbas Abbey, Dorset.

Milton Abbas Abbey, Dorset. St. Ethelwold’s most beloved foundation outside Winchester was Thorney, where he used to spend time as a hermit during Lent, where he dreamed of ending his days in the future (a dream which was never fulfilled), and where he built a splendid church with an apse at either end—perhaps due to Byzantine influence. When the historian William of Malmesbury visited Thorney in the twelfth century, he noted that it was “like Paradise on earth.” At that time, Peterborough, Ely, and Thorney were situated on islands amid nearly impassable swamps; the bogs were subsequently drained. Finally, in 974, St. Edgar established a monastic community in Eynesbury in Cambridgeshire on the bank of the River Ouse, and placed it under the protection of St. Ethelwold (a portion of the relics of the Cornish saint St. Neot was translated to this abbey and the town of St. Neots later grew up around it).

St. Ethelwold was able, energetic, hard-working, and austere—both to himself and others. He was very zealous and demanding regarding all Divine things done for the glory of God. It was said of him that he was as formidable as a lion with the rebellious and unruly, yet as meek as a dove with the obedient and God-fearing. An author of his Benedictional calls him “Boanerges,” that is, “a son of thunder” (a nickname applied by Jesus to the Apostles James and John in Mark 3:17). When he was the abbot’s assistant at Glastonbury, St. Ethelwold urged the monks to be more zealous in their monastic observance; it was said that the most sincere monks always loved and admired him, while the jealous disliked him and once attempted to poison the saint but the poisonous food did not affect the holy man at all. At Glastonbury, his obediences included cooking; there is one case of the multiplication of meat through his prayers.

The saint himself labored so much and so tirelessly that he slept very little and cared little for his health, which was weak throughout his life; he suffered much from a bad stomach and sore legs. Despite all this, he was one of the most energetic hierarchs of the age who lived in asceticism and prayer to the end of his days. The saint never slept after matins (3:00 am) and when he once fell ill, St. Dunstan managed to persuade St. Ethelwold to eat some meat—and he did so only out of obedience to his spiritual friend. At Abingdon, Ethelwold worked with his own hands, growing vegetables in the garden, and as the builder of the monastic church—once he even fell from scaffolding and broke his ribs; by the grace of God he was soon cured. At Winchester, he and some of his monk-builders built a very powerful organ. It was played by two people and had 400 pipes and thirty-six bellows. This organ could be heard from a great distance. It was used only for royal ceremonies. Not only was he a skilled builder and cook, he also excelled in metalwork; he himself cast bells for Abingdon, made censers, chalices, and candlesticks of gold and silver for its church. Following the example of his ninth-century predecessor, St. Swithin, who had built the first bridge over the river in Winchester, St. Ethelwold constructed the first aqueduct (water supply system) at Winchester to provide monastery brethren and neighboring city residents with piped water.

St. Ethelwold preferred not to have any possessions of his own. Before becoming a monk, he gave all the riches of his parents to the Church. During his time as a bishop, whatever was given to him, he would at once distribute among the poor and needy. All the money he received, the saint devoted to rebuilding churches. When famine broke out in the country, the archpastor ordered that church treasures and silver vessels be melted down and sold and that the proceeds be given to the famine-stricken. “What is lifeless metal in comparison with the bodies and souls of human beings, created by the Lord and redeemed at a high price?” he said. Numerous disciples and followers of St. Ethelwold from Winchester, Abingdon and other monastic centers he restored would become celebrated abbots, bishops, and missionaries in the future. Some of them, in the following eleventh century, went to Scandinavia as missionaries and were later listed among the saints of God.

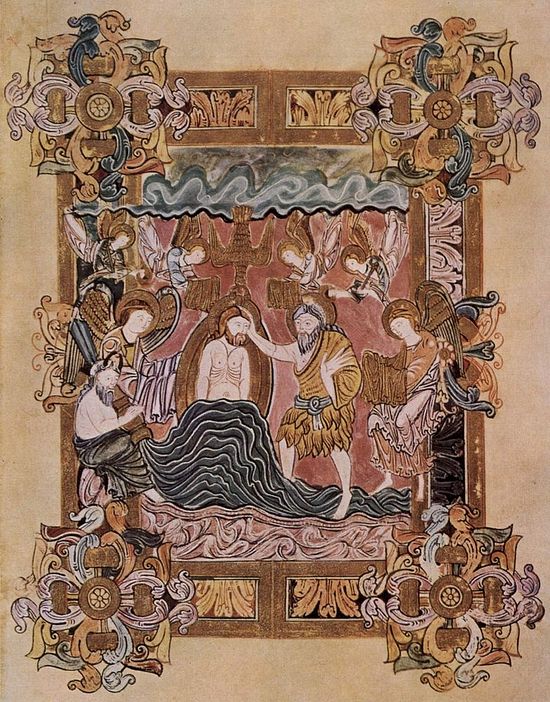

Ethelwold built the first scriptoria at Winchester and, under his influence, the Winchester style of manuscript illumination was introduced into many English monasteries and cathedrals. These, according to evidence of that time, even surpassed products of many scriptoria in continental Europe. One of the high points of tenth-century illumination is the Benedictional of St. Ethelwold. The scribe of this Benedictional was monk Godeman from Abingdon, whom St. Ethelwold commissioned to produce this masterpiece at Winchester, after which the latter became Abbot of Thorney. It is very richly and lavishly decorated and has twenty-eight page miniatures. The Latin text contains blessings uttered by a bishop during the Liturgy. Each day of the liturgical year and each saint’s feast-day had a separate blessing. There were highly-ranked feasts of Sts. Swithin of Winchester, Etheldreda of Ely, and Vedast (a French saint). It also contains a blessing of candles for the feast of the Meeting of the Lord. Several distinctive blessings were composed at Winchester itself. Today this precious Benedictional, which experts regard as one of the best examples of early English art, is kept at the British Library in London.

Ethelwold founded a famous and important school for vernacular writing in Winchester. Its scholars, among other things, made accurate and distinct linguistically relevant translations of sacred and spiritual texts from Latin into their native Old English. This huge task was absolutely vital, especially for English priests and bishops who were not monks. This contributed to Old English becoming the literary language of the English state. The most prominent scholar connected with this school is, beyond doubt, Aelfric of Eynsham (c. 955-c. 1020), a celebrated spiritual writer, homilist, and hagiographer of the age; he was a pupil at Winchester. (Aelfric of Eynsham is not to be confused with St. Aelfric of Abingdon (+1005, feast: November 16/29), who was a monk and abbot of Abingdon and was later raised to the rank of Archbishop of Canterbury).

Ethelwold was a talented writer, poet, and translator; some of his written works survive. His work includes: a treatise on the circle, glosses on St. Aldhelm’s work On Virginity, the gloss on the Royal Psalter in Old English, and his translation of the Rule of St. Benedict and of “Regularis Concordia” (a sort of a handbook of monastic practice, see below) into Old English. Ethelwold also created works of Church art, but, unfortunately, none of them survive.

Liturgies at Winchester monasteries were rich and varied. Ethelwold’s Winchester was famous for producing the first collection of polyphonic singing in England (in two or more parts each having a melody of its own), called the “Winchester Troper.” The Troper (from the Greek “troparion”) probably contains the earliest large collections of two-part music in all Europe. Firstly, it comprises more than 160 examples of two-part pieces, probably composed by Wulfstan the Cantor, whom St. Ethelwold knew. For a long time, it was thought that the music in the Troper could not be deciphered and sung. However, modern scholars have enabled this music to be both played and performed, even publishing recordings available today on CD. Secondly, it comprises a complete liturgical drama with music, making it the earliest extant European play with music! The Troper is comprised of two separate manuscripts, one of which is kept at the Bodlean Library in Oxford, and another kept at Corpus Christi College of Cambridge University.

St. Ethelwold served as Bishop of Winchester for twenty-one years. Whatever he undertook was blessed by God, which is why his works had such a lasting effect. Three remarkable events marked the final years of his ministry. The first was the promulgation of the document called “Regularis Concordia” in 970, a code of monastic rules, compiled and developed mainly by St. Ethelwold, with the participation of Sts. Dunstan and Oswald, for the thirty reformed English monasteries. It was based primarily on the Rule of St. Benedict of Nursea, with some minor additions according to customs existing in Ghent (Belgium), Fleury (France), and Glastonbury. The second event was the translation of the relics of the wonderworker, St. Swithin of Winchester, in 971, into the magnificently restored Old Minster Cathedral of Winchester. From that time on, St. Swithin’s shrine was the destination of thousands on annual pilgrimages from all England and Europe, throughout the Middle Ages. The third event was the consecration of the Cathedral in Winchester in 980. This cathedral was destined to be one of the largest and greatest in all Europe and also a center for the arts. The grandeur and scale of that Cathedral have only recently been duly appreciated by scholars.

Each of these three events was marked by a large, solemn assembly of clergy, laity, and royalty, and the consecration of the Cathedral brought together nine bishops. The monasteries established or revived by Sts. Dunstan, Oswald, and Ethelwold in the second half of the tenth century provided up to three quarters of all the bishops in England, right up until the Norman Conquest. Over the span of twenty to thirty years, the spiritual picture had changed radically in England; monastic life, Church activities, family piety, education, various crafts, and the ascetic life were raised to a very high level. This was the “Silver Age” of English Orthodoxy.

St. Ethelwold was described by his contemporaries and biographers (Wulfstan the Cantor of Winchester and Aelfric of Eynsham) as “a venerable man,” “an exemplary pastor,” “a benevolent bishop,” “the father of monks,” a wise adviser of kings, a noted scholar, and a very practically-gifted man. The holy hierarch reposed in the Lord in Beddington in Surrey (now the Sutton borough of Greater London) on August 1 (according to the Old Calendar), 984, at a very advanced age. He had suffered from a grave illness in the final years of his life, but bore the suffering with patience. Soon afterwards, miracles began to occur near his relics and through his intercessions (for example, the healing of a blind man from Wallingford (Oxfordshire) was recorded). His relics were translated to the Cathedral by his successor in Winchester, St. Alphege, the future Archbishop of Canterbury and martyr.

St. Ethelwold’s relics were again translated and enshrined within the cathedral in 1111. In the twelfth century, an arm, a shoulder bone (humerus), a finger, a leg, and some hair of St. Ethelwold were translated to Abingdon Abbey. From time immemorial, he has been deeply venerated in England, especially in Winchester, Abingdon, Glastonbury, Ely, and other places closely associated with him. According to the great historian of Anglo-Saxon England, Professor Frank Stenton (1880-1967), St. Ethelwold did not enjoy the affection of many academics until recently, perhaps on account of his “harsh dealings” with some secular priests who were driven away from Cathedrals and estate owners whose lands were transferred to the Church. Not long ago, his great achievements as a scholar were also recognized. His contribution to the political unification of tenth-century England was great, and his ability to build a symphony of relations between the Church and the royal power was deeply impactful. From the Orthodox point of view, his role as a restorer of old English spirituality, monasticism, and piety is immense, even if at times his actions were seen as extreme. Finally, it is thanks to Ethelwold and his companions that the English vernacular became the language of English culture and literature.[2]

Today, a parish church in the village of Alvingham in the English county of Lincolnshire is dedicated to “St. Adelwold,” which is a corruption of the name “Ethelwold.” The only church of St. Ethelwold in Wales is situated in the town of Shotton in Flintshire, near the border with England.

* * *

Let us say a few words on the sites associated with St. Ethelwold. The principal center of his veneration is the ancient, 900-year-old Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Sts. Peter, Paul, and Swithin, in the Hampshire city of Winchester, which attracts a permanent influx of pilgrims. It is 169 meters (556 feet) long, making it the longest English Cathedral. Old Minster, Ethelwold's beloved creation, lay just to the north, and partly beneath the present Cathedral. It was the chief Cathedral of Wessex from 660 till 1093, when the Norman Bishop Walkelin demolished the Old Minster and built the edifice which stands there today. Many Anglo-Saxon (pre-Norman) kings of Wessex and bishops were buried at Old Minster and, after its demolition, their remains were interred in the present Norman Cathedral. Under Oliver Cromwell, the iconoclastic Puritans committed a kind of pogrom inside the Cathedral and, as a result, these early English remains were scattered. After the “Commonwealth” was ended, the surviving relics were assembled and placed inside the mortuary chests which can still be seen in the Cathedral today. Some fifty years ago, extensive excavation work was carried out on the site of the Old Minster, and the area is currently marked by brickwork close to the Cathedral. Some finds from the site can be seen in Winchester City Museum.

New Minster was founded in Winchester, close to the Old Minster, in 901. Alfred the Great purchased the land right before his repose and the work was completed by his son Edward the Elder. It was a royal monastery, and its first abbot was St. Grimbald (formerly a monk at St. Bertin in France), who helped restore learning in the country (feast: July 8/21). This monastery possessed the relics of St. Alfred, St. Grimbald, the Breton saint St. Judoc, and even the head relic of St. Valentine. After the Norman Conquest, the community of New Minster was forced to move outside the north walls of the city, to a place called Hyde—thus Hyde Abbey was founded, a successor of New Minster. Now Hyde is an area within Winchester and the ruins of Hyde Abbey are still preserved there (notably the gatehouse, amid the abbey gardens).

The Nunnaminster, or Convent of St. Mary, was founded by the widow of St. Alfred the Great, and the building was completed by Edward the Elder. Among its first nuns was Edward’s daughter named Edburga, who shone forth with her holiness (+ c. 960, feast: June 15/28). St. Ethelwold introduced strict Benedictine discipline into the nunnery and installed an elderly and experienced nun, Aethelthryth, as its new abbess. The convent was rebuilt after the Norman Conquest, but fell victim to the war between Stephen and Matilda and lay in ruins for a while. The convent was eventually restored and even flourished until the dissolution under Henry VIII.

Abingdon Monastery was dedicated to the Mother of God. It is said that St. Helen had preached there in the fourth century, and, in the seventh century, St. Birinus, the enlightener of Wessex, built a church in honor of St. Helen on this site which still exists, although it was later enlarged. The first monastery was founded in Abingdon in about 675 by Prince Cissa of Wessex and it slowly gained prominence. St. Ethelwold reestablished it as a Benedictine house and life prospered in this abbey until the Reformation. It produced many learned abbots and monks and the famous Chronicle of Abingdon was compiled in the twelfth century. Abingdon is the birthplace of Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury (1234-1240), who is venerated by Roman Catholicism as a saint.

Today, Abingdon is a very picturesque small town on the River Thames, south of Oxford. The twelfth-century Church of St. Nicholas of Myra, which was originally attached to the abbey gates, stands in the town intact. The church walls were later rebuilt and the chapel is of the fifteenth century. It preserves a warm atmosphere inside. Among its treasures are stained glass windows displaying scenes from Christ’s parables. Also, six years ago, when a wooden panel was removed from an inner wall, an ancient painting of a crown and leaves was discovered intact behind it. Minor ruins of the abbey are behind the church, located in the “Abbey gardens” and “Abbey meadows.” Nothing survives of the original monastery church. From former monastic buildings, a bakehouse, a hostel for pilgrims, a gallery, and a gateway do survive extant. Another gem of the town is its sixteenth-century “monks’ map,” which was created by the abbey brethren 500 years ago on parchment and paper, and depicts the surroundings of the town, particularly the River Thames. It is now preserved at Abingdon Museum.

In the Middle Ages, Abingdon was a holy site, housing a huge number of relics, including a part of the True Cross, fragments of its nail, some minor relics of St. John the Baptist, Apostles Peter, Paul, Andrew, James, and Bartholomew, of the martyrs Stephen, Laurence, Sebastian, Victor, Pancras, George, and Edmund, many relics of St. Edward the Martyr, along with some relics of Sts. Cedd, Aldhelm, Ethelwold, and many other saints. This monastery even claimed an arm of St. John Chrysostom. Clearly, it was an important destination for pilgrims.

Thus the memory of the Holy Bishop Ethelwold remains among the faithful for future generations. Holy Hierarch Ethelwold of Winchester, pray to God for us!