For over 1000 years St. Frideswide (also spelled Frithuswith, Fritheswithe, Fritha, Fris) has been venerated as the patron saint of Oxford (“oxen ford”) in England and for over half of millennium, as the heavenly patroness of Oxford University and its students. However, very little genuine information on this saint survives. There is no early Life of St. Frideswide (whose name means “peace-strong”). Although she was a contemporary of the Venerable Bede, he does not mention her in his History of the English Church and People because he did not have informants on that part of Mercia where she lived.

The historian William of Malmesbury related the story of St. Frideswide early in the twelfth century, which was followed by other Latin versions of her Life in the same century; but the best known of them is the account made by Robert of Cricklade, Prior of St. Frideswide’s Monastery in Oxford between 1150 and c. 1175, who was a very prolific author. The thirteenth-fourteenth century hagiographic work known as the South English Legendary also contains a narration dedicated to Frideswide’s life. In the modern age the life of this saint was thoroughly researched by Professor John Blair. All of the medieval stories have numerous discrepancies as to minor details of Frideswide’s life, yet they agree on the major facts and events associated with such an important saint. Let us recall them.

The future saint was born about 680 (according to another version, about 665) in western Oxfordshire, which was then a province of the large early English kingdom of Mercia, near the border with the kingdom of Wessex. Her father’s name was Dida (other forms: Didan and Didda), and her mother bore the name Sefrida (Saethryth). In all probability her parents were pious Christians. Dida was a sub-king of Mercia who ruled the area which included western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames in the same region. As a child little Frideswide was given by her parents to a woman of holy life called Elgitha, who brought her up at Didcot in Oxfordshire.

Under the influence of this woman young Frideswide came to love the Gospel, and she firmly decided to dedicate all her life to the service of God in purity and holiness. It was even said that the holy virgin Frideswide quickly learned by heart the whole Psalter at the age of seven. She began to live an extremely austere life when still a child. The teenager Frideswide ate only herbs and barley bread and drank only water. She kept vigil day and night and wanted to become a nun. The motto of Frideswide throughout her life was: “Whatever is not God is nothing.” Her mother died when she was still very young, and she returned to her father’s house. At that time a large part of Oxfordshire was all dense forest, while Oxford was still no more than a village and not widely known.

According to one version, Dida wanted to find a suitable husband for his beautiful and wise daughter, but learning that she vowed to remain a virgin and serve Christ in chastity, he approved her choice and at once arranged for her to be tonsured. According to another version, Dida knew of her decision from the very beginning: so he allotted lands at Oxford, Bampton and probably Eynsham to establish monastic communities and gave Oxford to Frideswide to rule. In any case, Frideswide, when still very young, was at the head of a community of devout nuns at Oxford, which soon became a double monastery (with communities of monks and nuns who lived separately but prayed in the same church) dedicated to the Mother of God.

All the late versions of Frideswide’s life recount how a prince (who is sometimes called a king or a sub-king) named Aelfgar (another form: Algar) sought Frideswide’s hand when she was already abbess of Oxford. The saint answered him that her only Bridegroom was Christ and she had taken monastic vows to serve Him her entire life. Furious, Aelfgar then decided to force the saint to marry him and even abduct her. Accounts of what happened later with Aelfgar’s plot vary, but in general all his evil intents failed by the grace of God. First he called his army of men to enter Oxford, take Frideswide and bring her forcibly to him. But when they approached the convent the men were suddenly blinded and all ran away in fear. On another occasion, Aelfgar arrived in Oxford himself, wishing to abduct the saint. Warned about this by an angel, Frideswide secretly fled, accompanied by two of her sisters. First they reached the River Thames and boarded a boat that had been miraculously prepared for them by Divine Providence. The nuns sailed along the River Thames until they arrived at a place that became their refuge for several years.

Different hagiographers and scholars identify that place with Binsey in Oxfordshire, Bampton in Oxfordshire and Frilsham in Berkshire. Though all of them are possible candidates—each of them is on the River Thames and has an ancient church and a holy well—Binsey is the nearest to Oxford (less than one mile away from the city) and has a clear early close connection with Frideswide, while Frilsham is far away, and Bampton has a patron-saint of its own.1 Whatever the truth is, the holy virgin and her companions settled in a former abandoned pigsty in thick forests near a well of fresh water where they lived a life full of prayer and contemplation. Some time passed. Aelfgar did not give up and tried to find Frideswide at any cost. He finally found Frideswide’s hermitage and was going to seize her, but the holy maiden prayed to the virgin-martyrs Catherine and Cecilia fervently—and the wicked man instantly became blind. Only after his sincere repentance, abundant tears and promise to leave Frideswide alone did the holy maiden pray for Aelfgar, allow him to wash his eyes in the holy well, and his eyesight was restored. From that time he never pursued Frideswide again.

The saint of God returned to Oxford where she served as an illustrious, wise, loving and caring abbess to her nuns and monks, gathering a very large community. She may have also opened a school and a hospital at the monastery. The saint took special care of the needy, the hungry, the homeless, the destitute, the oppressed and everyone who needed help. And God performed numerous miracles through her intercessions both in her lifetime and after her death. She healed the sick from many diseases, both physical and mental, and there are countless examples of them. Once she cured a woman who had been blind for seven years so that perfect vision returned to the latter. She also drove out a demon from a possessed man who had been cruelly tormented by a wretched spirit for a long time. On one occasion she exposed and sent away the devil himself who once appeared to her and attempted to tempt her through his flattery.

There is also a remarkable moving story how once a leper came up to Frideswide in the street and said: “O saintly venerable mother Frideswide! I beseech you to kiss me in the Name of Christ the Highest Lord!” The saint without hesitation made the sign of the cross and kissed this ugly man, as he asked. And, behold, he was completely healed by God at that very moment, so his skin became healthy, fresh and like that of a child. Biographers of Frideswide wrote that people who suffered from many kinds of ailments followed the saint wherever she went, seeking her prayers—and she cured them in the Name of God. The glory of the wonderful holy abbess and healer spread far and wide, and she was loved and venerated as a saint already in her lifetime.

In the final years of her life, Frideswide, who loved solitary prayer, with the consent of her community retired to a secluded place (probably Binsey) where she lived as an anchoress. It was there that a holy well gushed forth due to her prayers, and it has been known for its curative properties since that time—for nearly 1300 years. It is particularly famous for curing eye diseases with miracles occurring even nowadays. The holy woman reposed in the Lord in 727 (according to another tradition, in 735) and was buried at her monastery in Oxford, venerated by all. Unfortunately, all the early records of her monastery were lost due to an eleventh-century fire, but it is certain that she was held in high esteem, and her veneration spread all over Oxfordshire, Berkshire and probably several other neighboring counties.

Small portions of her relics were later transferred from Oxford to other monasteries, for example Reading Abbey in Berkshire, Hyde Abbey in Hampshire, Waltham Abbey in Essex and so on. And, most significantly, the town (now university city) of Oxford was founded, grew and developed around her monastery. Thus it is an amazing fact that a princess of a sub-kingdom of seventh to eighth-century Mercia contributed to the formation of such an important center as Oxford, which originally had been no more than a village amid woods. As early as in the Saxon era, Frideswide was declared to be the patron-saint of Oxford, and it was early in the fifteenth century that Oxford University declared her as its heavenly patroness—she remains such to this day. Although the exact date of Oxford University’s foundation is unknown, its rapid development began after 1167, and the first college appeared in 1249. Now this university has thirty-eight colleges.

Although the veneration of Frideswide was never nationwide, many pilgrims went to her shrine in Oxford and the holy wells associated with her. Cases of healing from blindness, deafness, dumbness, paralysis, various sorts of swellings, leprosy, dropsy, arthritis, ulcers, stones, sciatica, intestinal diseases, fever, barrenness, mental illnesses and insanity were recorded in great numbers. Kings and queens visited her shrine too, for example Henry III, Edward I and Catherine of Aragon. Members of the royal family helped this site develop as a center of learning.

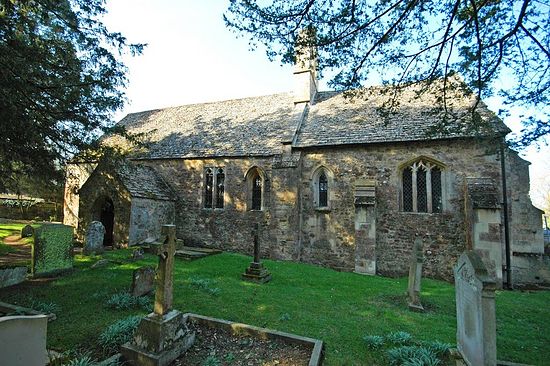

Today St. Frideswide is venerated especially by the Orthodox, also by Catholics and Anglicans. A twelfth-century parish church, standing on the site of a Saxon church, with a holy well in the village of Frilsham in Berkshire is dedicated to Frideswide. But the most popular destination is Binsey—a hamlet just to the northwest from Oxford, where there is a twelfth-century St. Margaret’s (St. Marina’s) Church with a holy well which appeared, as was said above, through the prayers of Frideswide. The church interior is very simple but the atmosphere of prayer, warmth and holiness is felt there by those who visit it.

The holy well is officially dedicated to St. Margaret of Antioch, but it is popularly known as “St. Frideswide’s well”. It is the prototype of the “treacle well” in the book Alice’s Adventures in the Wonderland! (The author of this book, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known under his pen name Lewis Carroll, was a mathematics lecturer at Christ Church College in Oxford—where St. Frideswide’s relics still rest at the cathedral. His books were inspired by Alice Liddell (1852-1934), a daughter of the then dean of Christ Church).

There are regular Orthodox pilgrimages to this well and the annual blessing of its waters by the local Russian Orthodox community. There are modern Orthodox icons of the holy mother Frideswide; she is depicted on stained glass windows of many churches in Oxfordshire and even beyond (for example, Gloucester Cathedral), her statues can be found in a number of churches. A modern parish church in the town of Milton Keynes in county Buckinghamshire is dedicated to her. Frideswide is even venerated in France with the name “Frewisse”. Her statue can be found inside St. Vedast’s Church in the village of Bomy in the Pas-de-Calais departement. Once there were also a chapel and a fountain dedicated to her in this spot, though the origins of this veneration are unknown. But let us now talk of the veneration of this holy woman in the city of Oxford.

The first Orthodox monastery founded by Frideswide in Oxford existed for several centuries. The monastery church was burned down in 1002 in the event which has come down to history as the “St. Brice’s Day Massacre”. It is named after St. Brice (Bricius), successor of St. Martin as the Bishop of Tours in Gaul (died 444) whose feast-day is on November 13. On that day, 1002, the English king Ethelred the Unready, after the repeated annual raids of Danes on English cities, ordered people “to kill all the Danes who can be found in England”. On that very day many Danes were killed there, though mainly outside the Danelaw territory. The Danes who lived in Oxford hid in the Church of St. Frideswide seeking sanctuary there. But the townsfolk set the church on fire in order to murder the Danes, so all of them were killed in that fire (over 600 in number), and the church destroyed. The saint’s relics most probably lay in the grave at that time, and in 1004 King Ethelred, as a token of his remorse, ordered St. Frideswide’s Church to be rebuilt and her holy relics returned to it. A community of secular priests was attached to it at that time.

After the Norman Conquest, in 1122, on the site of the Orthodox Monastery of the Mother of God a new, Catholic Augustinian Priory of St. Frideswide was established. It existed until the sixteenth century. The relics of Frideswide were solemnly enshrined in a new reliquary in 1180 with the participation of the Archbishop of Canterbury and other bishops and nobles in the ceremony, and over 100 miracles were reported over the following year. Another translation of her relics took place in 1289. In the Middle Ages the Priory of St. Frideswide celebrated the feast-day of its patron-saint twice a year: on November 19 according to the old calendar (the day of her repose) and on February 12, in memory of the translation of her relics. The priory enjoyed great fame, and many wealthy donors enriched it and gave generous presents. The priory possessed vast lands.

In about 1524 the Priory of St. Frideswide was suppressed by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (1474-1530), an important Church figure and statesman under Henry VIII, also former chancellor, who started building his magnificent new college there, giving it the name “Cardinal College”. He even demolished some west bays of the main church’s nave to give space to the new building, while the saint’s shrine remained intact. However, in 1529 Wolsey fell into disgrace with Henry VIII who accused him of treason. So the construction of the college was temporary stopped, and the cardinal died on his way to the court. Meanwhile, the Reformation began in the 1530s. In 1532 King Henry refounded the college which had been begun by Wolsey, naming it “Henry VIII’s College”, and the shrine of Frideswide was desecrated by iconoclasts in 1538, while a larger part of the church remained whole. In 1546, one year before his own death, Henry VIII established the new Diocese of Oxford, making the former priory church the cathedral and the chapel of the newly-founded university college at the same time. The college and the cathedral were named in honor of Christ the Savior—“Christ Church”. So Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, this former twelfth-century monastery church, remains a cathedral church and a college chapel to this day, which is a unique case in England.

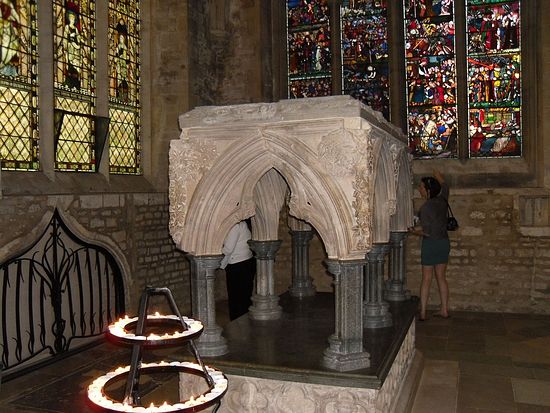

For several centuries Christ Church was the smallest cathedral in England, but in the twentieth century several smaller former parish churches obtained the status of cathedral as well. As for the relics of Frideswide, their destiny is unusual though somewhat tragic. They were reinstated together with the shrine in the reign of Catholic Queen Mary I Tudor (ruled 1553-1558) but were again desecrated after her death by radical Protestants. The shrine was broken into pieces, while the holy relics were mixed with the remains of Catherine Dammartin (a former nun), wife of the Zwinglian theologian Peter Martyr Vermigli, and buried under the floor. They remain so to this day. It was only in 1889 that fragments of the former shrine of Frideswide were discovered at the bottom of a well on the territory of Christ Church, and gradually and accurately reassembled during the twentieth century.

The shrine was completely restored and installed at the Cathedral in 2002, and it has been a destination of pilgrimages (as is the whole Cathedral itself) since then. It stands in the Latin chapel in which the saint’s relics were kept before the Reformation. Candles are lit by the shrine nearly all the time, and there is a very large stained glass window in front of it, created by the great painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), depicting sixteen scenes from the life of Frideswide. Orthodox and other pilgrims feel the presence of the patron-saint and a particular spiritual, peaceful atmosphere on this spot. As for the actual relics of Frideswide, they lie under the floor in an unknown location within the cathedral, and there is also a modern dark square slab in the middle of the Lady Chapel not far from her shrine, marked with her name “Frideswide”.

There are also banners of Frideswide at the cathedral which are carried annually by Orthodox believers and parishioners in processions in the memory of this great saint. Every year civic processions to her shrine are organized as well.

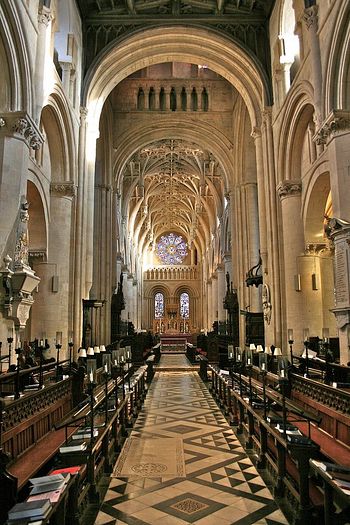

Christ Church Cathedral is built of the light honey-colored Cotswold stone. It witnessed and experienced many events throughout its history. For example, in the Civil War King Charles I made his headquarters in Oxford between 1642 and 1646 because it was the only large English city which remained loyal to the king. Charles resided at the deanery of Christ Church and frequently attended Cathedral services at that time. The Cathedral underwent restoration works in the nineteenth century carried out by George Gilbert Scott. Now its interior is among the most beautiful in England. It has one of the richest collections of high-quality stained glass images, ranging from medieval to nineteenth century. The oldest stained glass (dates back to 1320) at St. Lucy’s Chapel depicts the Catholic saint Thomas A Becket, the martyred Archbishop of Canterbury. During the Reformation the college was ordered to destroy this image, but the college workers only removed his face from the glass, thus saving it. Some windows were created by the seventeenth-century Flemish brothers Abraham and Bernard Van Linge. Other noticeable glasses depict Sts. Catherine and Cecilia (patrons of St. Frideswide); Sts. Faith, Hope and Charity; and the Archangel Michael fighting with the dragon.

The present church was built mainly between 1160 and 1200. The Cathedral spire is one of the oldest surviving spires in England and dates to 1230, as also the Lady Chapel. The Latin chapel that contains Frideswide’s shrine was completed by 1338. The only surviving former monastic buildings at Christ Church include the prior’s house along with parts of the dormitory and refectory. The elegant chapter house is dated to the first half of the thirteenth century, and has some fine carvings. The nave, choir, transepts and Cathedral tower are of the late Norman period (mainly between 1170 and 1190). The cathedral has features of the Romanesque, Norman, Early English Gothic, and Perpendicular Gothic architectural styles.

Among those who are remembered at this cathedral let us mention John Taverner (c. 1490-1545)—a great composer of church music who was an organist here; George Berkeley (1685-1753), an Irish philosopher and bishop who believed that material objects exist only by being perceived, is buried here; the philosopher and founder of empiricism John Locke (1632-1704) was among Christ Church students; John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism, were ordained here in the eighteenth century; Henry Liddell, father of “Alice”, along with Lewis Carroll—both mentioned above; Edward Pusey (1800-1882), a theologian, professor of Hebrew at Christ Church, and founder of the “Oxford Movement” in Anglicanism that strove to return to the early Church teachings and ceremonies, explored the works of early Church Fathers and finally became the basis of the Anglo-Catholic tradition (or the High Church) within the Church of England; William Penn (1644-1718), a Quaker and founder of Philadelphia in the United States, after whom the state Pennsylvania was named, was its student. Christ Church has produced no fewer than thirteen prime-ministers, noted bishops and statesmen.

Christ Church is entered from St. Aldates Street of Oxford. At the entrance to the college is the bell-tower known as “Tom Tower”. It was designed by the architect Christopher Wren in 1681-1682. It contains the famous ancient bell, “Great Tom”, weighing 6.25 tons and the loudest bell in Oxford, which still rings 101 times every night. Oxford also has three so-called “Protestant Martyrs” who were executed here on the orders of Mary I Tudor and are venerated by the Anglican Church. The Queen accused them of heresy and they were burned at the stake. They are: Hugh Latimer, former Bishop of Worcester and adviser of the king (1485-1555); Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London (c. 1500-1555); and Thomas Cranmer, the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury who compiled the Anglican Book of Common Prayer (1489-1556).

There is a nineteenth-century Anglican Church of St. Frideswide situated in Botley Road, West Oxford. It was built between 1870 and 1872 and contains, among other things, the “Alice door” in the nave—this door was carved by Alice Liddell, the prototype of “Alice in Wonderland”. A square situated to the west of central Oxford is called “Frideswide Square” in honor of the city’s patron-saint. St. Frideswide is usually depicted as a crowned abbess with a staff, with a spring gushing forth near her, with an ox at her feet, and sometimes as rowing up the Thames together with two nuns and an angel.

Holy Mother Frideswide of Oxford, pray to God for us!