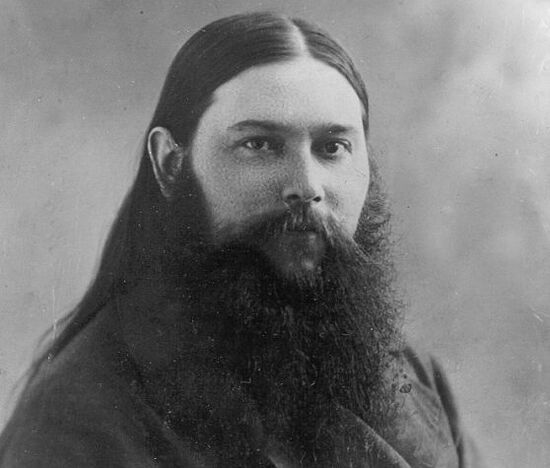

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk). Photo: newmartyros.ru

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk). Photo: newmartyros.ru

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir was born on July 15, 1888 in Poland, in the town of Lukov, Siedlec province, to the pious family of railroad worker Thaddeus Medvediuk. When his father was dying, he said to his son Vladimir, “My child, how I would like to see you as a priest or even a reader, but only as a servant of the Church.” His son replied that that is also his own desire.

Having graduated in 1910 from theological school, Vladimir served as a reader in the Radomsky cathedral in Poland. The peaceful course of life was interrupted by the first world war, and Vladimir Fadeyevich, like thousands of others, became a refugee. When he arrived in Moscow, he met Varvara Dimitrievna Ivaniukovich, who came from a deeply religious family in Belorussia and was a refugee like him. In 1915 they were wed.

In 1916, Vladimir Fadeyevich was ordained a deacon for the Church of Martyr Irene, on Exaltation Street in Moscow. He served there until 1919 and was ordained a priest for the church at the St. Savva of Storozhev metochion on Tverskaya Street. In 1921 he was assigned as rector of the Church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh in Petrovsky Park, Moscow.

The Church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh, Moscow.

The Church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh, Moscow.

From the first days of his service in the Church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh, Fr. Vladimir began to set parish life in order. This parish became an island of love amidst the ocean of passions, calamities, and sufferings that was soviet Russia of the time. The young priest was a zealous pastor, and faithful young people were drawn to him. He strove to cultivate love in them for Orthodox services and the church. To the Church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh there often came visiting choirs from various churches, which also attracted many worshippers and lovers of Church singing, so that there were times when the church could not fit all those who wished to pray there.

Renovationist Bishop Antonin (Granovsky). During the bacchanalia of renovationism when schismatics were brazenly seizing churches with the help of the godless authorities, in order to avoid such forceful seizure Fr. Vladimir would close the church after services himself, and take home the keys. Seeing that they couldn’t take the church without this priest’s consent, the renovationists invited Fr. Vladimir to the renovationist bishop Antonin (Granovsky). The latter demanded that Fr. Vladimir give him the keys to the church, shouting at him:

Renovationist Bishop Antonin (Granovsky). During the bacchanalia of renovationism when schismatics were brazenly seizing churches with the help of the godless authorities, in order to avoid such forceful seizure Fr. Vladimir would close the church after services himself, and take home the keys. Seeing that they couldn’t take the church without this priest’s consent, the renovationists invited Fr. Vladimir to the renovationist bishop Antonin (Granovsky). The latter demanded that Fr. Vladimir give him the keys to the church, shouting at him:

“Give me the keys!”

“I won’t give them to you, Vladyka, I won’t!”

“I’ll kill you! I’ll kill you like a dog!”

“Go ahead and kill me,” the priest replied. “We’ll stand together before the throne of God.”

“Well how about that!” said Bishop Antonin, but he didn’t make any more demands. And the renovationists were unable to take the church.

In 1923, Fr. Vladimir was awarded with a kamilavka.1 In 1925, the authorities arrested the priest and after naming fabricated accusations against him, and threatened him with imprisonment and labor camps. He could only be freed, as they said, by consenting to collaborate with the OGPU. Fr. Vladimir gave his consent to this and was freed. The OGPU gave him some assignments, mainly concerning the Locum Tenens [of the Patriarch] Metropolitan Peter, which he fulfilled. But the further he went, the worse his conscience tormented him. Neither his zealous service in church nor his pastoral conscientiousness could assuage that burning pain in his soul. Finally Fr. Vladimir decided to cut his ties with the OGPU as a secret collaborator and confessed his sin of betrayal to his father-confessor. On December 9, 1929, an investigator of the OGPU subpoenaed him to one of the offices on Bolshaya Lubyanka Street and demanded an explanation of him. Fr. Vladimir stated to him that he refuses to collaborate any further. For three whole days they tried to persuade him to change his mind, but Fr. Vladimir resolutely refused, declaring that anyway he’s already told everything to the priest in confession. On December 11 an order for his arrest was signed, and he was accused of “disclosing… information that should not be divulged.” On February 3, 1930, the Collegiate of the OGPU sentenced Fr. Vladimir to three years of imprisonment in the labor camps, which he served at White Sea Canal construction sites.

Meanwhile his family was evicted from the parish house and left without a roof over their heads. This is was the priest feared the most. While in the camps, he prayed fervently to St. Sergius of Radonezh and to the saint’s parents, Schemamonk Kirill and Schemanun Maria, that by their prayers the family might find refuge. And they did find refuge in Sergiev Posad [where the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra is located]. At first they were aided by Olga Seraphimovna Dedendova, a well-known benefactress of the time, who in the 1920s took care of Metropolitan Macarius (Nevsky) in the St. Nicholas-Ugresh Monastery.

St. Elias Church in Sergiev Posad.

St. Elias Church in Sergiev Posad.

In 1930 on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross of the Lord, Fr. Vladimir’s son Nicholas went to the St. Elias Church in Sergiev Posad. When he went up for the anointing, the rector of the church, Fr. Alexander Maslov, said to him:

“This is the first time I’ve seen you in our church, young man.”

“We are in dire straits, batiushka,” said Nicholai. “There are five of us, and they’ve taken papa. Mama and Olga Seraphimovna have been around the town for two days. As soon as people hear that there are five children, no one lets them into their apartment. We don’t know what to do.”

Fr. Alexander called up one parishioner and said to her, “Nadezhda Nikolaevna, you yourself are in great grief—you should understand and receive this family.”

“Bless,” she answered.

That is how they ended up in the Aristov family. The head of the family, a deacon of the Church of the Exaltation, had been arrested and shot just a few months earlier. This home become the refuge of Fr. Vladimir’s family for many years. After the end of his prison term in 1932, Fr. Vladimir lived here with his family, and travelled to Moscow to serve in the Church of St. Mitrophan. In 1933, the church was closed by the authorities, and Fr. Vladimir was appointed to the Holy Trinity Church in the village of Yazvishche, Volokolamsk region.

In 1935, the priest was raised to the rank of archpriest. In Yazvishche Fr. Vladimir was given small living quarters with two windows in the church guardhouse, to which his entire family soon moved. It was crowded, but the parish had no other place. One day a neighbor who lived across the street came to him and said, “Fr. Vladimir, I am offering you my house. Live there as long as you want. I won’t take a kopeck from you.” Fr. Vladimir lived with his family in that house for ten years.

The Holy Trinity Church in the village of Yazvishche, Volokolamsk region.

The Holy Trinity Church in the village of Yazvishche, Volokolamsk region.

At that time in Volokolamsk region there were many who had returned from exile and were forbidden to live in Moscow. Among them was Archdeacon Nicholai Tsvetkov, whom the faithful revered as a clairvoyant ascetic. Archpriest Vladimir often went to him to resolve one or another difficult matter. One day, Archdeacon Nicholai asked him to serve that night in his home. The windows were shuttered. They vested. There were but a few worshippers. Then suddenly during the service, someone knocked at the window. With the prison and the camps freshly in his memory, Fr. Vladimir began removing his vestments. “Fr. Vladimir, don’t be fainthearted. Stand where you are. Now we’ll find out who it is,” said Fr. Nicholai. As it turned out, knocking on the window was an incidental traveler who wanted to know how to get to the station.

The last time Fr. Vladimir came to Archdeacon Nicholai was in spring of 1937 in order to greet him with his name day. But the latter did not even come out of the house. He only stood behind the door and said, “Christ is Risen!”—and that was all. Fr. Vladimir was disturbed and asked the righteous man’s assistant to tell him that Fr. Vladimir from Yazvishche had come to greet him with his name day. She passed this on, and Fr. Archdeacon repeated to her, “Tell him: In Truth He is Risen!” Fr. Vladimir was very upset, because he understood that the clairvoyant elder was saying this as a sign that they would not meet again in this life.

In 1937 mass arrests began. In November Archpriest Vladimir went to Moscow, and when he returned, he said that he was sure he would soon be arrested. “I am not afraid of exile or death,” he said. “I’m afraid of the prisoners’ convoy, when they drive the prisoners on for several dozen kilometers a day. When some falls down from exhaustion the guards beat him to death with rifle butts, and then the wild animals tear apart their corpses.”

On November 11, 1937, in the regional office of the Volokolamsk NKVD, a report came that in the village of Yazvishche a meeting was held at which there were practically no young people. And supposedly there were none because not far from the meeting hut, Fr. Vladimir’s son Nicholai had gathered the local youth into a little house church. In the report was also stated that twenty people go to the priest daily, mainly old men and women from various collective farms of the Volokolamsk and Novopetrovsk regions. On November 24, 1937, an order for the priest’s arrest was signed.

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk). Colorized photo from: klimbim2014.wordpress.com.

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk). Colorized photo from: klimbim2014.wordpress.com.

On November 25 Fr. Vladimir was to serve a Liturgy for the reposed and on the evening before, he read the priestly prayer rule by the window of his room. In that house, besides his family, there were two monastery novices—Maria Bryantseva and Tatiana Fomicheva, who after their monastery was closed were living at the Holy Trinity Church in Yazvishche, fulfilling their obedience as readers and alter attendants. That evening they were helping the priest’s wife slice the cabbage for pickling. Suddenly Fr. Vladimir saw the chairman of the village soviet and a militia man walking past his window. “It seems they’re coming for me now,” Fr. Vladimir said to his daughter. In a few minutes they were already in the house. “Let’s go to the village soviet. We need to clarify certain things,” one of them said. Fr. Vladimir started saying goodbye to everyone, but the NKVD man intentionally hurried him up, saying that he would soon be returning. But Fr. Vladimir knew that he would never return. He blessed everyone and said to his daughter, “We are not likely to see each other again my child.” The two novices Tatiana and Maria were also arrested with him.

On the same day, the priest’s wife Varvara Dimitrievna gathered a package and brought it to the village soviet, but they didn’t let her in to see her husband. They said that they would be coming back to her house in the evening for a search. Late that night the same NKVD man came and started searching the house with a furious clamor. The shelves cracked, and the books fell off. The search consisted finally of taking everything that came into his hands and throwing it all into a bag with no written description.

The interrogations began shortly after the arrest. On November 26, they called in the representatives of the village soviet who had participated in the priest’s arrest, the secretary of the village soviet, and the “shift witnesses,” who signed the statement of evidence written by the investigators. On that same day, Archpriest Vladimir was interrogated.

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk), after his arrest. Photo: newmartyros.ru “The investigation has information,” the investigator declared, “that nuns and believers from the surrounding villages of Volokolamsk and Novopetrovsk regions often visit your apartment. Give evidence on this issue.”

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir (Medvediuk), after his arrest. Photo: newmartyros.ru “The investigation has information,” the investigator declared, “that nuns and believers from the surrounding villages of Volokolamsk and Novopetrovsk regions often visit your apartment. Give evidence on this issue.”

“Fomicheva and Briantseva visited my apartment, but very rarely. The faithful visit my apartment only for religious needs.”

“It is known to the investigation that mobs form in your apartment. At those gatherings you discuss party politics and the soviet government.”

“There have never been any mobs in my apartment.”

“The investigation has information that you conduct counterrevolutionary and anti-Soviet agitation amongst persons around you.”

“I have not conducted counterrevolutionary and anti-Soviet agitation.”

“You are giving false testimony. A number of witnesses have been questioned about your case, and they confirm the fact of your anti-Soviet agitation. The investigation demands that you give truthful testimony.”

“I again declare that I have never conducted counter-revolutionary and anti-soviet agitation.”

On the same day, novices Maria Bryantseva and Tatiana Fomicheva were also questioned.

Novice Maria was born in 1895 in the village of Severnaya, Podolsk district, Moscow Governate to the family of peasant Gregory Briantseva. Her father had a small property—a house with outbuildings, two barns, a granary, a horse and a cow. In 1915, when the girl became fifteen, she entered a convent as a novice. After the revolution she labored in the Sts. Boris and Gleb Monastery in Voskresensk district until in was closed in 1928. That same year she left for her native village in Podolsk region.

Novice Tatiana was born in 1897 in the village of Nadovrazhnoe, not far from the town of Istra, Moscow Governate, to the family of peasant Alexei Fomich. In 1916 she became a novice in the convent, and after the revolution she had an obedience in the Sts. Boris and Gleb Monastery. In 1928 the authorities closed the monastery, and she moved back in with her parents in Nadovrazhnoe.

In 1931 the authorities began persecuting monks and nuns from closed monasteries. Many of them, despite the fact that their monasteries were closed, strove to uphold the monastic rule in their lives. Some settled not far from their monasteries, earning their bread by handicrafts like ancient desert dwellers, and they would go to the local parish churches for prayers. Thus the OGPU in early 1931 created a “case” against the nuns of the Exaltation Monastery, located next to the village of Lukino, Podolsk region. Before the revolution there were about a hundred sisters laboring in the monastery. After the revolution the monastery was closed, but the nuns managed to get permission to form an agricultural team within the monastery walls, made up of a few former sisters of the convent. Thus did monastic life continue there until 1926, when the convent was finally closed and the Karpov rest home was situated in its buildings. Twelve convent sisters stayed there even then, some working as rest home employees, others settling in the neighboring villages and doing handiwork. They would all go the St. Elias Church in the village of Lemeshovo for services. The parish choir was also made up of nuns and novices from closed monasteries. Singing in the choir were novices Maria Bryantseva and Tatiana Fomicheva.

Questioned on May 13, 1931 by an OGPU interrogator, the director of the rest home gave testimony that “in the former monastery, where the rest home is now located, there are still bells, crosses, wall carvings of icons, and various church embellishments hanging, and there is a church outside the monastery walls. Why the bells were not removed and the monastery was not brought to a normal appearance, it was hard to say. Nevertheless, the presence to this day there of twelve nuns and their anti-soviet activities gives us grounds to suppose that the rest of the population in the surrounding villages were under their influence and did not sign off on the removal of the bells. Twelve nuns make up nothing other than a convent, live at the monastery, are connected with the kulak2 element, agitate the peasants against events organized by the soviet authorities, often circulate amidst the peasantry, and have contact with the residents of the rest home, trying in every way to influence them, claiming they were deceived by the soviet authorities.”

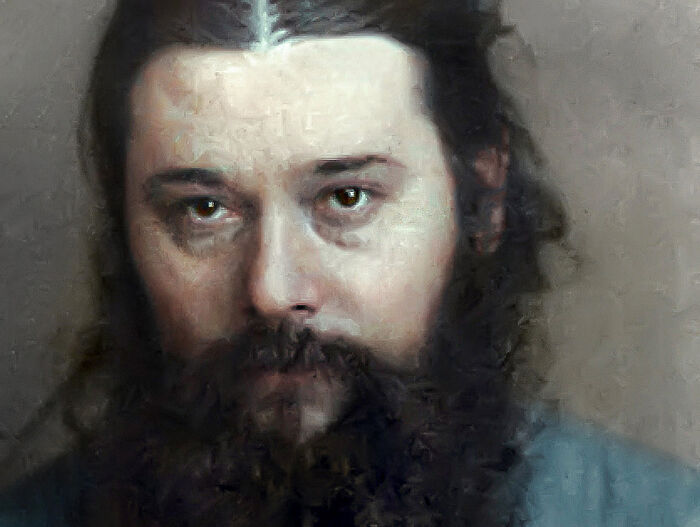

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir, icon. Under questioning by the OGPU, the cultural worker of the rest home gave evidence: “I will express my opinion on the ‘holy’ hotbed around the church. Although I have only encountered this hotbed two or three times during investigations of the locality, the cemetery, the church, and at that only very superficially, I have nevertheless clearly felt precisely a nest and hotbed that is at enmity against us, with their grim old ladies who send curses in our direction. It is characteristic to note how strong their influence is. The peasant girls up to twelve years of age with whom I have spoken near the church believe in God, and at my attempts to dissuade them they would at first listen to what I had to say, but soon wave their hands and go to the church, led by the old lady nuns. Last winter there were incidents seen where people in the rest home also went to church, and therefore it is my opinion that this hotbed should be liquidated entirely, even to the point of demolishing the church.”

Holy Hieromartyr Vladimir, icon. Under questioning by the OGPU, the cultural worker of the rest home gave evidence: “I will express my opinion on the ‘holy’ hotbed around the church. Although I have only encountered this hotbed two or three times during investigations of the locality, the cemetery, the church, and at that only very superficially, I have nevertheless clearly felt precisely a nest and hotbed that is at enmity against us, with their grim old ladies who send curses in our direction. It is characteristic to note how strong their influence is. The peasant girls up to twelve years of age with whom I have spoken near the church believe in God, and at my attempts to dissuade them they would at first listen to what I had to say, but soon wave their hands and go to the church, led by the old lady nuns. Last winter there were incidents seen where people in the rest home also went to church, and therefore it is my opinion that this hotbed should be liquidated entirely, even to the point of demolishing the church.”

On May 18, 1931, novices Maria and Tatiana were arrested and imprisoned in Butyrsky prison in Moscow. There were seventeen nuns and novices arrested in all, who had come from various convents and settled near the closed Exaltation Covent.

The mistress of the house in the village of Lemeshevo, where novice Tatiana lived, testified that the novice occupies herself with handiwork which she sells to the peasants of the neighboring villages, and that she is ill disposed toward events organized by the soviet authorities. One of the false witnesses testified that novice Tatiana is a fanatical church person and actively conducts anti-soviet activities. Another witness testified that novice Maria told the peasants, “Why do you need collective farms and why go to them when peasants are forced there. You peasants are now being corralled into a cowshed where no laws are written.” And the peasants supposedly shouted in reply to one of the novices’ words, “Matushka is right, after all, they know more than us.”

At the interrogation Maria said, “I relate to the soviet government with contempt. The soviet government has suffocated us. The communists have organized persecutions against the Church, closing churches and demanding huge taxes. I do not plead guilty to anti-soviet agitation.”

On May 29, 1931 a Troika of the OGPU sentenced novices Maria and Tatiana to five years of prison at a correctional labor camp. When they were released in 1934, Maria settled in the village of Vysokovo, and Tatiana in the village of Sheludkovo, Volokolamsk region, and began to assist Archpriest Vladimir in the Holy Trinity Church. They were arrested with him in 1937.

Interrogated on November 26, 1937, the novices categorically refused to confirm the accusations brought against them by the investigators, and did not agree to give false witness against anyone. On November 28 the investigation was closed, the next day an NKVD Troika sentenced Archpriest Vladimir to execution, and novices Tatiana and Maria to ten years of imprisonment in a correctional labor camp.

At that time, Fr. Vladimir’s wife Varvara Dimitrievna was informed that the prisoners are being sent to Moscow and the train would be passing through the station nearest them at 3:00 p.m. She was told that the prisoners would be in the first car, with bars on its windows. Varvara Dimitrievna and the children went there with their things, which she thought she could give to her husband. The train stopped, but the car with the prisoners was surrounded by guards, who wouldn’t let anyone get close. The famiy peered attentively at the barred windows and suddenly saw a hand there, blessing them with a priestly blessing. The train stood at the station for three minutes, which seemed but a moment to them. After the train pulled out they had no strength to walk the three kilometers home carrying the things they had brought for Fr. Vladimir. At that moment a youth who lived in Yazvishche walked up to them and asked them what had happened. They explained everything, and he helped them carry their things home.

Archpriest Vladimir Medvediuk was shot on December 3, 1937 and buried in an unknown common grave at Butovo firing field, south of Moscow. He was ranked among the New Martyrs and Confessor of Russia at the Jubilee Bishops Council of the Russian Orthodox Church in August 2000 for general Church veneration.

Novice Maria Bryantseva returned home after her prison term ended, and novice Tatiana Fomicheva died in prison.