The blue February twilight is quickly descending upon the city. We’re walking around the center of old Tbilisi—the abbess of the Monastery of the Transfiguration of the Lord, Matushka Mariam (Mikladze), is waiting for us to come. We can’t find the entrance to the small monastery for a long time—it’s completely unnoticeable in the tangle of ancient streets and courtyards.

We knock on the first door we find facing onto the street, and to our great joy, a nun opens. We enter into the sewing workshop, walk right through it and we climb up the hill along a multitude of stone steps for quite some time, to the main monastery buildings.

Once there was a palace here—King Irakli II built it for his beloved wife Daredjan. Then it housed a theological seminary, and from 1824, the men’s Monastery of the Transfiguration. Catholicos-Patriarch Ambrose (Khelaya), now glorified as a confessor, lived here from 1906 to 1908. Under the Soviets, the monastery, of course, was closed and a museum in honor of the Twenty-Six Baku Commissars was located here. The monastery returned to the Church only in 1991.

A small tower with supporting pillars and an open-work wrap-around balcony—an observation deck remained from the palace of Queen Daredjan. A beautiful panoramic view opens up from the balcony on the fully-lit evening Tbilisi. Perhaps this is only part of the former palace of the queen, but, most likely, it was built this small: Georgian royal palaces were usually not large. There is a church next door, and planted lawns with roses and palms growing. Since 2003, there is an active hospice in the monastery, a training facility for sisters of mercy, and sewing and iconography workshops.

We finally reached the tower. Abbess Mariam, thin as a rail, light, dainty, rushes to meet us—she looks very young. Matushka answers our questions and tells us about herself and about the monastery.

—Matushka Mariam, could you share with us how you came to God?

—I never doubted that God exists, but I was born in 1964, and it was the time of atheism. In school we joined the Pioneers,1 they showed Brezhnev on TV a lot, and it seemed like it would be that way forever. I did well in school, and would even go to the famous Pioneers’ camp “Artek.”

I had nightmares in my childhood. I asked my mama to baptize me, and they baptized me when I was fourteen. I was baptized together with my sister, although my mama remained unbaptized.

Once I had a really strange dream that I died. It left such a strong impression on me that I still remember it, thirty years later. It was like this: There was a pannikhida. My friends were sitting on one side of my casket, and my grandmother on the other side. At first my friends wept over me, and then they began to speak about what was going on in their lives, about some plans they had. I felt deep sorrow because I wouldn’t be able to join them in these plans anymore. But I could speak with my grandma—somehow she heard me. What a strange dream.

A little while later I went to see the play “Our Town,” in which the main character dies and has the same experiences as in my dream. It’s all pretty strange, but I still have very vivid memories of this dream; it was the first time I thought about death, and the remembrance of death appeared in me. And even now, when I’m at a pannikhida, I always feel I must choose my words, and think that the soul of the deceased can hear me, because the soul does not die.

There’s another time I remember well, when I was faced with death: My friends died on a yacht—something happened with the electricity. It was very scary, because two weeks before the tragedy I was on the yacht, and it all could have happened to me. Facing death never goes unnoticed—it always forces us to think about the meaning of life, about the Creator, and about what will be beyond the mortal threshold.

After high school I entered the biology department of a university in Tbilisi, but I never believed in the theory of evolution; I knew that every living thing has a Creator. I became friends with Ketevan Makhviladze there, who is now the abbess of the monastery in Bodbe, Mother Theodora.

—And you went to church?

—Yes, I first went to a service in church as a student. I barely understood anything of what was going on there. It was Pascha, and the parishioners were loud, joyful—and I did not clearly understand anything. I was watching the priest: He was hearing confessions the entire night. I spent the whole night at the service and sat down from fatigue, and the priest stood the whole time, attentively listening to people. I thought: He must be so tired! I’m sitting, and he’s standing the whole night!

Then I saw how he rejoiced in Pascha, how happy he was… Such a heavenly joy was on his face that he involuntarily passed it to me and I also felt an unearthly joy when I looked at him.

Then I went up to him for Confession—it was the first Confession in my life. I was struck by how this unknown priest understood me with half a word, as if he knew me my whole life. I didn’t know then that the Lord reveals to his pastors what is necessary for the salvation of their flocks.

Then this priest became my spiritual father—Fr. Daniel (Datuashvili). He was a very spiritually gifted man. Fr. Daniel received the monastic tonsure in 1991 with the name David. In 2002, he was elevated to the rank of metropolitan.

I later met His Holiness Patriarch Ilia II. His Holiness attracts people like a magnet. My generation, who are now abbots and abbesses of monasteries, and rectors of churches—we are all his spiritual children.

I began my Church life, and everything was just as written in the Gospel. It was the rebirth of spiritual life in Georgia, and the Lord bore us, spiritual youths, in His hands, giving us, as a loving Father, everything we needed that we prayed for. He comforted us with His mercy, and we had joy like the first Christians; and it all happened by the prayers of His Holiness.

—How did you first come to the monastery, and what did you feel then?

—Once I was driving with my neighbor and we saw Fr. Daniel trying to wave down a taxi. We offered him a ride and he said he was going to Mtskheta, to Samtavro Monastery. We drove to Samtavro, and I felt there that I didn’t want to leave the monastery, that I had to stay there and pray. The Lord Himself led us there through our spiritual father, and I unexpectedly said to my neighbor, “Please, when you return home, go see my parents and tell them I’m not lost—I’m staying overnight in the monastery.”

At that time, the very oldest matushkas were laboring in Samtavro—no one was younger than them—and they left me to spend the night with one elderly nun in her cell. It was my first meeting with a monastery, and it was an indescribable joy! I felt such strong grace that I didn’t want to go anywhere from there…

I met an elderly nun in Mtskheta—Matushka Rakhil. How she prayed! She knew how to pray… One nun was seriously old there, and Mother Rakhil prayed for her fervently and boldly. She asked, “O Lord! You led the tanks out of Georgia—so lead the sickness from this seriously ill nun…”

Her prayer was so alive! It was even like she didn’t ask, but demanded with confidence and hope in the mercy of God…

The matushkas of this monastery were so elderly that they couldn’t care for the monastery, they didn’t have the strength to keep up with the farming, but by their example they taught us the main monastic activity—prayer. And they were very busy, sincere people; they have a living relationship with the Lord; they felt His presence in their lives. Mother Rakhil would weep when we prayed inattentively…

—And the monastic way of life gradually grew on you?

—Yes. After graduating from college I got a job in the Scientific-Research Institute of Biophysics. But the secular life attracted me less and less; I started to avoid loud gatherings, and lost interest in all worldly comforts. With the blessing of my spiritual father, Fr. Daniel, I left work.

Then my friend Ketevan Makhviladze (now Abbess Theodora) quit work in the Scientific-Research Institute. We had one other friend, Matushka Elizabeth (Meskhishvili), who is now also the abbess of the missionary stavropegial Monastery of St. Nino in the village of Foka at Paravani Lake.

We, youth, united around our spiritual father, Fr. Daniel, and His Holiness suggested that we all together dedicate one day a week to working in abandoned churches and monasteries; we would work there and then pray and eat together. His Holiness also blessed us to pray on our prayer ropes—it was already close to monastic life.

His Holiness later blessed us to spend a month at Pukhtitsa Monastery, where the tradition of the monastic life was passed from generation to generation. Thus, the monastic way of life was getting closer and closer for us. Then His Holiness blessed us to live at Samtavro Monastery, where I got to know the great saint of our times Fr. Gabriel (Urgebadze). I spoke about our meetings with him for the book The Elder’s Diadem.

—Did your parents immediately accept your choice of the monastic path?

—His Holiness himself tonsured me as a nun. At first my parents were against it and very worried, but, by the prayers of His Holiness and Fr. Gabriel, they accepted my choice.

My mama came to see me in the monastery once on the eve of the feast of the Theophany of the Lord. I really wanted to pray at the services in church for this feast, but I was given the obedience to be with a sick nun in oncology. I asked her to let me go to the service for a bit, and of course she let me go.

I hurried to the monastery to make it for the festive Liturgy, but along the way I began to worry that I wasn’t fulfilling my obedience and had left the patient. I went back to the hospital and felt comfort and certainty that I had done the right thing.

To my great surprise, having returned to the monastery after fulfilling the obedience, I found out that my mama confessed and communed for the first time at this feast. Thus the Lord comforted me, as if saying to me, “Bear your obedience, and I will do all the rest Myself.”

—Matushka, please tell us about how you became the abbess.

—After Samtavro, they moved me with Matushka Theodora and Matushka Elizabeth to the village of Martqopi, one of the most ancient villages of the Caucasus. There are many historical monuments in Martqopi, which you can find even in local residents’ yards, for example, the centuries-old tower.

St. Anthony Martqopsky, one of the founders of Georgian monasticism, labored in these places in the sixth century. He was called Martqopsky due to his love for solitude: “Marto mkopi” means “being in solitude.” For the last fifteen years of his life he labored in asceticism on a pillar, and after the saint’s death, a multitude of healings took place at his grave.

We built a church here in honor of St. George. We were young girls, and it was very easy for us. St. George greatly helped—almost all of the benefactors who supported us were named George. Well, everyone knows who builds churches—it is, first of all, the saints.

I became the abbess of Iveron Monastery in Martqopi at twenty-seven years old. It was completely unexpected for me: His Holiness gave me no warning, and I did not expect it at all.

When I found out about the coming abbacy, I was a little afraid. Fr. Gabriel (Urgebadze), now canonized as a saint, predicted my abbacy, but said it wouldn’t be soon. Once he said to me, when I was still novice Nino, “You will become an abbess in twelve years.”

But I became an abbess much earlier. At first I was puzzled: Why didn’t the saint’s prophecy come true? Only later did I understand. Precisely twelve years later I said to myself, “Alright, I’ll be an abbess!”

I needed time. Those twelve years had to pass to grasp this and take up my cross…

From 1991 to 1995 I labored as the abbess of Iveron Monastery in Martqopi. We built a church and established an order and life. I had just gotten somewhat used to my abbacy in a small monastery when they appointed me abbess of Transfiguration Monastery in the center of Tbilisi.

—How did you take this new assignment?

—At that time, the Lord, earlier having borne us in His hands, as spiritual infants, began to gradually teach us to walk with our own feet, as a mother teaches a child to walk. A baby falls, gets bruised, and asks to be held again—everything was so good for him when he was held… I wept for three days having learned of my impending appointment, but it was my new obedience.

And now I have been here for twenty years already. The monastery is in the center of Tbilisi, and it is very noisy here, especially in the summer: Music roars all night. The heat. How we can overcome it, I don’t even know... With God’s help. When we rise with the sun to pray, the music stops, glory to God. We have sixteen sisters: two novices, one riassaphore, and the rest are full nuns. We are like one family.

—Tell us a little about the order in your monastery, please.

—We get up at 5:00 AM. Prayer finishes at 7:30. At 11:00 is trapeza. After trapeza until 5:00 PM—obediences. At 5:00 is the second trapeza, and then the evening prayers. After prayer, we disperse to our cells.

We leave time for rest, for reading spiritual books, for the cell rule of prayer. The sisters need time for rest so they can comprehend why we labor—and we labor for God, for the salvation of our souls.

There are various obediences: the garden, flowers, we make candles, we bake prosphoras, bread; one sister paints icons, another translates spiritual books; laundry, cleaning, embroidery; work in the guest house.

Is it difficult for me to maintain discipline in the monastery? You see, the Lord sends me sisters who are very self-disciplined, and I don’t have to be very strict.

—I have heard that a hospice operates in the monastery…

—Yes, we also have a school for sisters of mercy and a small hospice with six beds in the monastery. Girls, having gone through the training, care for cancer patients in the city and those who demand daily care they bring to our hospice.

They usually bring the sick to us in a very serious condition. Sometimes they remain with us for a time, and sometimes until their very end. Some of them, having lived in our hospice, receive monastic tonsure.

Qualified sisters of mercy care for the sick, and we have catechetical talks with them; we just chat and spiritually support them.

Some of these terminally ill people have taught us much in the last minutes of their lives, by how they met their deaths. They have taught us patience, love, and hope. We see how the Lord helps them, and we are grateful that the Lord has given us this ministry.

—It’s not an easy ministry…

—No, but we have had many miraculous situations connected with it. Once, we had one young girl lying in the hospice. She was dying from cancer. She wanted to become a nun, and we tonsured her. Just then, Patriarch Theodore II of Alexandria was visiting us; he came to visit His Holiness and came to us as well. He proposed, “Tonsure her with my name, in honor of the same saint I was tonsured for, and I will pray for her.”

We tonsured her with the name Theodora. Then we had the tonsures of other sisters, and Mother Theodora really wanted to be there, to rejoice for the newly-tonsured, and again experience the grace of the monastic tonsuring. But she was too weak. She apparently prayed that the Lord would give her this joy, and she truly was able to be present at the tonsure—but in a casket. And of course, the monastic tonsure is also a death—the death of the old man and the birth of the new. A new person is born, with a new name.

The boundary of death as if did not exist at this tonsure—we saw that death does not exist.

—Perhaps you recall some other edifying stories?

—When His Holiness appointed me as abbess of this monastery, I remained the abbess of the monastery in Martqopi for a short time too, and the sisters of Martqopi came to our monastery in Tbilisi to the monastic tonsure.

We had one novice who was a psychiatrist in Martqopi, and it just so happened that she herself got sick with a mental illness. Her intellect was fully preserved, and she understood what was happening to her; she comprehended everything. But over time the veil of the disease so strongly darkened her mind that it became very hard for her, and she lost contact with reality. She really wanted to go the tonsure together with the sisters, but her condition was worsening, and she was in such a serious condition that we even didn’t tell her about the trip.

When we returned to the monastery after the tonsure, she opened the door for us, and we saw with amazement that she was perfectly healthy. The veil of the sickness left her mind, and she was able to think quite reasonably and understood everything. We were simply floored, to be honest. The people were probably stunned like that when Lazarus rose from the grave. You should have seen the serious condition of this mentally ill person before we left, and her perfectly healthy and clear state of mind afterwards.

And we understood: It costs the Lord nothing to heal anyone, even the most seriously ill person! She told us there was a moment when she was as if doused with cold water, and she recovered her sight and was cured. This moment perfectly coincided in time with the moment when the monastic tonsure, that she was wanted to go do, was being celebrated! And we understood that everything is possible for the Lord!

This sister is an example of how God can heal any person if it is His holy will. Then this sister became a little worse, but it wasn’t as bad as before anymore; her mind was never so darkened again.

Her case is an example of how a person patiently bears his cross. This occasion was the most important for her—something changed in her, and we all believed in the miracle. Now this sister is a nun.

—Did meeting such people leave the biggest impression on you, Matushka Mariam?

—Would you like me to tell you about meeting the Optina elder Schema-Archimandrite Iliy (Nozdrin)? I saw the elder sitting at the table, and so wanted to get to know him closely, that I just went up and sat next to him. Then someone came over whom I disliked. Then I saw with what love the elder looked at him, and I realized how Fr. Iliy loves people and judges no one. I saw myself against the background of the elder, and it was a lesson for me!

Another time, after I was already abbess, I went to America. My friends, Michael and Ketevan, wanted to introduce me to Bishop Basil (Rodzianko). The flight was delayed, and when I got to my friends’, Vladyka had already left. I was very upset; I really wanted to meet him…

Vladyka Basil didn’t even know me, but when they told him how upset I was, not having caught up with him, he said, “I will come again specifically to meet her!”

And he came. When I saw Vladyka I was simply amazed—he was shining! He was like a breath of fresh air! And he gave me strength, supported me. When Vladyka served the Liturgy I was outside of time, outside of space…

My friends, Michael and Ketevan, told me about Vladyka Basil. Michael (now a priest in Georgia) shared that when he had just arrived to Americ, he was very despondent. He was sitting in church once after a service, totally depressed. Vladyka was tired after the service, and he didn’t know Michael, but he didn’t pass by, but went up to this man sitting in the church, comforted him, and then became his spiritual father.

You know, sometimes I have a feeling—I feel warmth coming from some people. Such warmth of grace came from St. Gabriel (Urgebadze), such warmth comes from His Holiness, and I felt the exact same warmth from Bishop Basil (Rodzianko)… It is joyful, not fearful, with such people, and you feel at home! Such people always remind me of God, because they are like Him!

I also really liked the books of Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. When we went to America, we specifically flew through London—I so wanted to see Vladyka Anthony. We buzzed at the door of the church where he served. Someone opened the door, and we saw a man standing in a waistcoat and slacks. His face was very familiar. I imagined Vladyka nearly sitting on the clouds—and here he was opening the door to us, as a simple gatekeeper or watchman… I asked with confusion:

“Is it you, Vladyka?!”

“Yes, it is I.”

“And I thought you were the guard…”

“And I work as the guard here.”

Then Vladyka Anthony said, “I’ll go put my cassock on—I don’t want to shock you.”

He came back in his cassock. He was different and similar to Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) at the same time. Joy and life emanated from them both…

Metropolitan Anthony remained in my memory as a very modest and humble person. He set up a meeting for us with the Georgian diaspora and created a wonderful atmosphere, while himself remaining in the shadows.

—Matushka Mariam, which of the saints do you most often turn to for prayerful help in difficult situations?

—The saints are always near to us. Each person has the saints that he most often turns to for aid, with whom he feels some special spiritual closeness.

When there’s some kind of trouble, or misfortune, I turn to St. Nicholas the Wonderworker for assistance. Once we were going to the airport in a taxi, hurrying to our flight to America. I had already gotten into the taxi, when suddenly my nephew came up in his car and offered to take us to the airport.

I switched cars, and we had already gotten to the airport when suddenly I realized I had left the bag with my documents and money in the taxi. There was barely any time before the flight—where to find this car and driver?! My nephew was also bewildered—he hadn’t paid any attention to what kind of car the driver had. I said to St. Nicholas, “My dear Father Nicholas! You can do anything! You are quick to hear! As you wish—but please, find my bag!”

I had just addressed the holy hierarch when my nephew suddenly cried out, “I remember!”

He remembered that the taxi driver had a Volvo. My nephew immediately called to the center, and the taxi arrived to us momentarily, and the driver returned my bag whole and unharmed. I made it to my flight peacefully. This is our quick-to-hear St. Nicholas Wonderworker.

There was another time when I went to Italy. I was planning to go to St. Nicholas’ relics in Bari. I was completely alone, and somehow I got lost. I didn’t know which way to go, where the train station was, where to buy a ticket. I asked everyone walking by in English, but no one wanted to talk with me; everyone whisked by at full speed, not even listening to me. I was at a loss. No matter who I asked, no one answered. A foreign city; unfamiliar people.

And I prayed, “St. Nicholas, I’m coming to you!”

Immediately, a woman approached me, and I didn’t even stop her or ask her anything, but she was interested in what kind of problem I had and how she could help me, and she explained everything to me in English, about the road, and about the train to Bari, and about tickets. Such an immediate answer to prayer! Quick-to-hear St. Nicholas the Wonderworker…

St. Nina… You don’t have to ask her anything—she just helps! When things were hard for me, I would somehow find myself at her grave, and she would give me strength. She had such strength and such unwavering faith, and she shares this faith and strength with us. She helps His Holiness and Georgia.

The holy Nun-Martyr Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna… Her life made a great impression upon me. She also helped the sick and the infirm as we do in our monastery, so she is especially close to us. She really helps me by her example.

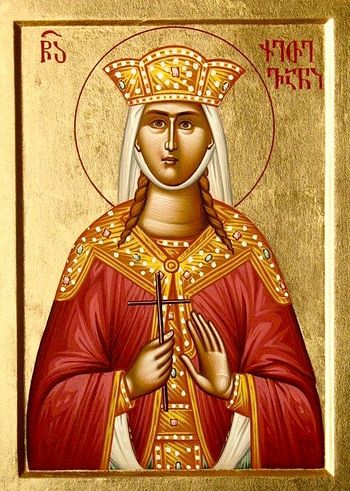

I really love the holy Great Martyr Ketevan (1565-1624). She was the queen of the Eastern Georgian Kingdom of Kakheti. She had an extraordinary life—very difficult. By the standards of earthly life, she never had joy or comfort.

She was widowed early. After the death of her husband she dedicated herself to the construction of churches, monasteries, and hospitals. She loved her country, and her country was taken away. Shah Abbas I threatened to turn Georgia into ruins, and St. Ketevan sacrificed herself: Wanting to prevent a war, she went to the shah with rich gifts and even offered herself as a hostage in place of her people. They tortured her, they tortured her grandchildren—they were thrown into a dungeon where they suffered for ten years. A very difficult life!

The shah proposed that she become his wife and demanded that she convert to Islam, but neither torture, nor bribery could break St. Ketevan. Many abandoned her and she remained completely alone, but she was steadfast as a rock. She saved all of Georgia! A great saint! Extraordinary faith and love for God! She saw how others were renouncing their faith in exchange for earthly life and earthly blessings—but she stood like a pillar.

St. Ketevan was also very beautiful. The one thing that she asked for—that they not undress her before her tortures—even that they did not fulfill. They left her no human consolations. The body of the great martyr was rent by red-hot hooks, but before every torture she would bless herself with the Sign of the Cross and say, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” At the end of her tortures, they poured a pot of burning coals on her head, but she remained faithful to Christ until the end.

I never ask this saint for anything—what can you ask such a saint for?! But it is a fact that she exists, gives strength, and fortifies people in faith. You know—sometimes people become despondent, or they begin to pity themselves. Then it is helpful to remember the holy Great Martyr Ketevan.

—Thank you for this wonderful conversation!

—God bless!