The worship of the Orthodox Church is closely connected with the sacred history of the Old and New Testaments. It as if illustrates this history from the very beginning, symbolically and spiritually, deeply connected with it.

That is why the rite of the All-Night Vigil begins with the doxology to the Holy Trinity: “Glory to the Holy, Consubstantial, Life-Creating, and Undivided Trinity, always, now and ever and unto ages of ages!” That is, God has always been: before time, before the creation of the world, and we must glorify Him. The choir answers on behalf of the people, “Amen,” which translated from Hebrew means “Truly,” or “Let it be.” Then is read the prayer of worship of the Holy Trinity, “O come let us worship…” and the 103rd psalm is sung, during which the priest and deacon perform the censing of the entire church and the congregation.

The 103rd psalm also begins with a doxology to God: “Bless the Lord, O my soul”—a picture of the creation of the world is visualized. The beginning of Vespers is a symbol of the eternal and pre-eternal existence of God—the Holy Trinity—and the creation of the world by the Most High. Every verse of this psalm is filled with deep meaning. So, for example, part of the first verse, O Lord, My God, Thou art very great; Thou art clothed with honor and majesty, tells us that God is incomprehensible and unapproachable in His essence for angels and men alike. He is higher and more powerful than anything in the world, clothed with honor and majesty.

The holy prophet and king David unfurls before us a huge panoramic canvas of the creation of the world, which corresponds to the first book of the Old Testament—Genesis. The Lord is clothed in unapproachable light and stretches out the heavens just as easily and powerfully as man stretches skin (103:2).

The idea of the creation of the heavens is then developed further. In the beginning of the third verse, Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters, it tells about how before the flood the Earth was covered by a ring of water that was above the firmament—the visible heavens, the atmosphere. We read about this in the Bible: And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day (Gen. 1:6-8). This ring later collapsed from the heavenly abysses during the flood on Earth and devoured every living thing upon it, except those saved on Noah’s Ark. The 103rd psalm also speaks about the creation of the clouds, the wind, the invisible spiritual world, and the ministering spirits—the Heavenly angels. The psalmist tells us that the holy angels are ministers of God, agents of His will throughout the universe.

Further, we learn from the psalm of the wise ordering of the world: about the mountains, the plants, the animals, and man.

The twenty-sixth verse in particular requires an interpretation: There go the ships: there is that leviathan, whom thou hast made to play therein. Exegetes interpret this particular sacred text in two ways. Thus, Prof. Alexander Pavlovich Lopukhin of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy believes that the leviathan, or serpent (translated as “dragon” in Russian), is some kind of ancient animal (a dinosaur in modern terms), which is described elsewhere in the Old Testament, in the book of Job, in the concluding chapters (40 and 41), and is also called there “leviathan” (from the Hebrew for “twisted,” “coiled”). It’s not a modern crocodile, but a great armored beast, which is practically impossible to kill with a bow, an arrow, or a spear. St. Athanasius the Great gives another interpretation of the verse, seeing in the image of the serpent an allusion to the devil, who tempted the holy forefathers Adam and Eve. This is confirmed by the final words of the verse in Slavonic: “ругатися ему”—which Thou hast created to be mocked.

The final verses of the psalm say of the source of life, the Lord: Thou hidest thy face, they are troubled: thou takest away their breath, they die, and return to their dust. Thou sendest forth thy spirit, they are created: and thou renewest the face of the earth (vv. 29-30). That is, if the Lord removes His Spirit, then creation will disappear, and if He sends His Spirit, then creation happens and will live.

The psalm also concludes with a glorification of the Lord. In the last, thirty-fifth, verse, Let the sinners be consumed out of the earth, and let the wicked be no more. Bless thou the Lord, O my soul. Praise ye the Lord, we see an allusion to the fall of the devil with his demons, and the very first people.

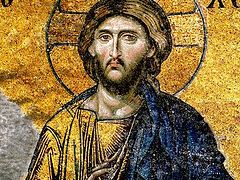

These words conclude the sacred history of the world before the fall and begin its second phase: the Old Testament, life in coats of skin, and the expectation of hundreds of generations for the coming Messiah.

This is why in liturgical practice the 103rd psalm is called “introductory.” It’s singing at the beginning of the All-Night Vigil, and the opening of the Royal Doors, and the censing of the entire church and the congregation signify Paradise and the direct communion of God and the first people. The censing of the congregation by the priest is a symbol of the fact that the Lord abided together with man and walked among them. But the Royal Doors are closed at the end of the psalm. It is a symbol of the driving out of man from Eden. It begins the history of contrition, repentance, and the battle with the devil and sin. It begins the history of the man’s waiting for the Deliverer-Redeemer—our Lord Jesus Christ. And the Divine Liturgy is an illustration of the Incarnation of the God-Man.