Judging by my experience of communication with Orthodox clergy in the UK over several years of my life in this country, their attitudes to Orthodox missionary work in the British Isles vary. Some priests believe that Roman Catholics and Anglicans are “our brothers and sisters in Christ” and don’t really need to comprehend the Truth of the Orthodox faith. Some representatives of the clergy are focused on the mission among the emigrants of their own nationalities (Russians, Greeks, Romanians, etc.) only. Finally, there are mission-oriented priests who view Britain as a vineyard with an abundant harvest that is in need of reapers—competent, active and loving ones.

As a rule, priests who do missionary work among local residents are themselves converts to Orthodoxy from other Christian denominations. For them the differences between Orthodoxy and heterodoxy (Catholicism and Protestantism) are very serious. They tend to be skeptical about ecumenism and don’t agree that “all religions lead to God” because their conversion to Orthodoxy was a highly motivated and well-thought-out decision, achieved through much suffering.

A decision in principle helped them abandon their denominations (even if they were cradle Catholics or cradle Protestants) in order to overcome all obstacles and join the Orthodox Church.

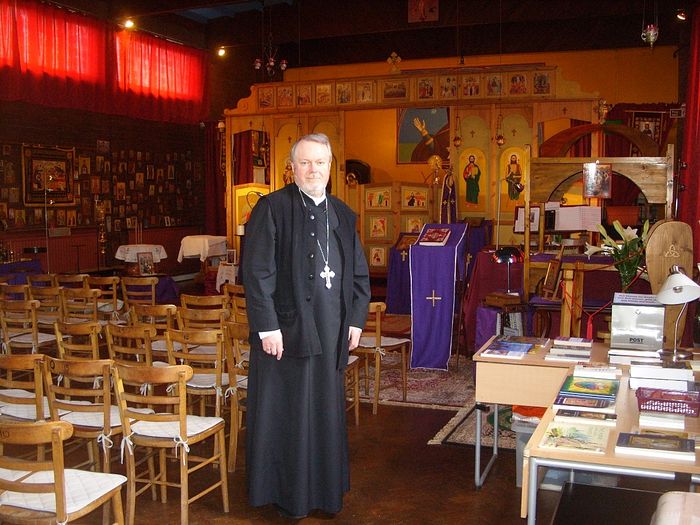

Over the years spent in Manchester I got to know one of such priests fairly well—Fr. Gregory Hallam, rector of the Church of St. Aidan of Lindisfarne in that city. Fr. Gregory had previously served as an Anglican priest, but in 1992 he became disappointed in Anglicanism and embraced Orthodoxy. Three years later he was ordained and since then has served at a parish of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch in Manchester—one of the largest English cities—for over twenty years.

“The ordination of women is not the only reason”

Those who know at least a few facts about modern religious history of Britain remember that in the early 1990s some Anglican priests and lay-people left the Church of England. The main reason was the decision of the C of E General Synod to allow the ordination of women. Most of the dissenters then escaped into the Roman Catholic Church, while some of them chose to join the Orthodox Church. However, as Fr. Gregory explained to me, for him the admission of women to the ministry of the Church of England was not the only reason (and even not a key reason) why he left Anglicanism. The choice in favor of Orthodoxy and not Catholicism had solid theological ground. He told me about it during our talk at St. Aidan’s Church in Manchester.

—Fr. Gregory, why did you convert to Orthodoxy?

—There are several reasons why I chose Orthodoxy and not Roman Catholicism. First of all, I couldn’t accept the total obedience to the Pope. Secondly, I had more and more doubts about the truth of Western Latin theology, not least about its concept of salvation and the Passion of Christ. More than that, I saw that Catholicism was a faith that was cut off from the Church Fathers and isolated from our English tradition.

—But what do you mean by the term “English tradition” in this context?

—Let me explain. Before the Norman Conquest of 1066, thousands and thousands of saints who, as I believe, belong to the Orthodox world, lived in these Isles. Of course, this question requires some additional examination, but what I do know is that the Russian Church included the names of a few British saints to its calendar. However, between 1066 (I think this date is more important for England than 1054) and the time of the Reformation only thirteen individuals living in this country were canonized1. But is it true that over that period Britain produced almost no ascetics who devoted their lives to the service of God?... Unfortunately, at that time the procedure of canonization became extremely expensive and complicated due to political reasons and the administrative centralization in Rome, so our people were deprived of holy men. It was a real problem for the English Church in the medieval period.

—Let us now return to the discussion of liberal practices in Anglicanism…

—Not only is it a matter of practice, it is also a matter of theory…

—Still, in the 1990s the Church of England was not as liberal as it is now. But today the C of E is considering gay ordinations and recognizing “same-sex unions”. The first women bishops have recently appeared in the UK, whereas in the early nineties only the ordination of women to priestly office was on the agenda.

—Let us first talk on the ordination of women. I am of opinion that priestly ministry could be conferred on ladies only by the fullness of the Church and at a conciliar level. I find it totally unacceptable if a schismatic Church structure that once broke away from the schismatic Catholic Church structure has the courage to declare that it is possible to change the fundamental aspects of Church ministry prior to its approval at any Pan-Church Council. By the by, I was present at the meeting of the C of E Synod before the vote on the women’s ordination and listened to a speech by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. He was invited to the Synod and said that the decision to ordain women would have a considerably negative effect on the dialogue between Anglicans and the Orthodox. However, the patriarch’s statement was not commented on, and the C of E decided to admit women to the ministry.

This notorious decision is also controversial as it caused a split within the C of E and a situation when some canons and the internal structure of the Anglican Church became conflicting and illogical by nature. The C of E has its own system of canon law; according to canon A4, a person ordained by a canonical Anglican bishop shall be recognized in his office by all Anglican parishes. In other words, you have no right to say that one or another ordained priest (or a lady priest) is not a priest and that you don’t accept his ordained ministry (only because you don’t like him or her). At the same time, there are some “flying bishops” [formally: provincial episcopal visitors.—Trans.] in the C of E who minister to the communities that object to women priests. The following paradox has emerged: On the one hand, in accordance with canon A4 the fullness of the Church must accept women priests who were ordained by canonical Anglican bishops, and, on the other hand, the Church has allowed some clerics and lay-people to disagree with women’s ordained ministry, which comes into conflict with canon A4.

I was personally present at an assembly of the clergy that disapproved of the ordination of women. So I said very directly that those decisions—in the context of the “flying bishops” and the provisions of canon A4—were an insult to the ladies whom it concerns; a departure from the catholic (in the sense: “universal”, “orthodox”) ecclesiology; the creation of a Church inside the Church; and a defiance of canon law. If the C of E had really been confident that the ordination of women was the will of God or the will of the Church, it would have been better for it to act differently, namely to begin with the ordination of women as bishops not as priests. After all, a priest receives his office and authority from a bishop. But in liberal Protestantism the decision-making mechanism is different: first you promote women rights and people get used to it; then you begin to praise one or another lady priest and do it until people say, “Oh yes! The Revd. Sarah is wonderful! She is a brilliant candidate for the episcopacy!” But it is a completely wrong approach!

—Fr. Gregory, you mentioned that there were other reasons (except the ordination of women) for leaving the Church of England.

—Yes, that’s right. And while the ordination of women was “the last drop that overflowed the cup”, this “cup” was filled gradually with various problems. The fundamental reasons for leaving Anglicanism were different. The issue is not that the sacraments and ordinations administered by women bishops and women priests are “unnatural” (that is, a deviation from the Scripture, as conservative Protestants of the West claim), but that the relationship between the Scripture and the Tradition is being destroyed.

In fact the ordination of women naturally ensues from the fundamental problem of Anglicanism—the lack of understanding of the necessary authority of the Church empowered to make important decisions. How can we know what is right and what is wrong in the Church? Those with the liberal Protestant mindset are incapable of answering this question. But for me the following point was even more crucial: the general concept of salvation in Western Christianity. As the years go by I am increasingly convinced that the concept of salvation in Eastern Orthodoxy differs so drastically from that of Western Christianity of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. In essence, Catholicism and Protestantism are “two sides of the same coin”, and their only serious difference is in the understanding of sacraments in the Church.

—Fr. Gregory, in this context I would like to mention the work by Archbishop Sergius (Stragorodsky) The Orthodox Doctrine of Salvation. The hierarch (the future Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia) in detail explained the striking differences between the Eastern Orthodox and the Latin soteriology. The difference between Western Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism) and Orthodox Christianity is not slight and superficial, but fundamental. It is in the understanding and explanation of the way man walks the path of salvation and reaches the Kingdom of Heaven. And salvation is the most essential thing for each Christian, so there can be no compromises here.

The problems of the C of E and the Orthodox mission

Having discussed the fundamental differences between the Orthodox Church and Western Christian denominations, Fr. Gregory and I step by step somehow got onto a tricky subject—the current situation of the Church of England. And it is not a matter of the disagreement among the modern sociologists and theologians about the line of development of the C of E today. As for Fr. Gregory, he has a clear opinion on this point, complete with a vision of the missionary role of Orthodoxy.

—In truth, the Church of England is experiencing real problems. Parishes are being closed, while the faithful are dwindling. But what should we, Orthodox Christians, do in this situation? Will we observe the extinction of Christianity in our native country with indifference until it is replaced by another religion, like Islam? After all, it is a matter of salvation of souls. Maybe we, Orthodox clergy and laity, ought to become more mission-oriented and abandon this “diaspora mentality”? As I see it, the only Orthodox Church (among the Churches whose jurisdictions cover those living in the UK) to have such capacity for missionary work is the Russian Church! And now I cannot help but recall St. Nicholas (Kasatkin) who founded the Orthodox Church in Japan along with the missionaries who preached the Gospel in Siberia and Alaska. These preachers had a good idea of how to bring the Glad Tidings of Christ to people of absolutely different nationalities and cultural traditions.

Of course, I well understand why the Moscow Patriarchate is striving to cooperate with heterodox Christians on a number of moral issues and matters. But I think that we cannot re-Christianize Europe by joint resolutions on “same-sex marriages” or euthanasia only. We hold regular assemblies and conferences, adopt various resolutions, yet only the return to Orthodox Christianity can save Europe. However, it can happen provided that missionaries appear in Europe—that is, Orthodox priests and bishops who will be concerned not only for the Russian diaspora, but also for the native residents of European countries.

—I agree with your opinion. But I would like to pay attention to one practical issue. I wholeheartedly support the Orthodox mission among the non-Orthodox—Catholics and Protestants—and among those who don’t know the faith of Christ at all. However, in many places of Western Europe the Russian Church is dependent on Catholics and Protestants. They often lease their churches, chapels and prayer rooms to Orthodox communities for worship. Maybe this fact accounts for the hesitation of the Patriarchate of Moscow in its missionary work in the West? For example, they fear that they will lose their rented premises (which they found not without a challenge).

On hearing these words Fr. Gregory looked at me with a hint of irony in his eyes.

—With due respect, Sergei. Do you know what an Englishman means by these words? They mean “nonsense”. Thus, I meant to say that your arguments are “sheer nonsense”.

—But why?

—Because if Moscow had such desire it could invest in the building of churches in the West. The reality is such that most of Orthodox communities in the West—Russian, Greek, Romanian and so on—are financially self-sufficient. For instance, we acquired the church building that we use for worship—it belongs to us and is not rented. However, at the very beginning we had no money and our community consisted of only twenty people. A year later we acquired our own building and over twenty years the congregation grew from twenty to 200 people. In addition, I receive allowance as a priest. And we have no external sources of finance.

—Meanwhile, it is known that the Church of the Protection of the Mother of God of the Moscow Patriarchate in Manchester was built with the help of one famous Russian oligarch…

—In our case, we managed to do everything without outside funds. But Russia is not a poor country. I think it could afford building six large churches in major cities of Britain and sending missionary priests there who would serve in both English and Church Slavonic. This project is realizable provided there is a will.

—Then, in your view, why are they still unwilling to do it?

—I believe the reasons behind their reluctance have nothing to do with apprehension or the unwillingness to offend the Protestants whose buildings and premises they have rented. It is not a satisfactory answer to this question. May I ask you about your opinion in return?

—To my mind, the problem is in certain theological mindsets of a number of the Russian Patriarchate’s hierarchs and clergy who don’t see any fundamental difference between the Orthodox and the heterodox. If a Catholic remains Catholic and a Protestant remains Protestant, they find nothing wrong in it. These representatives of the Church believe that the most important thing is being a Christian regardless of your denomination.

—But are they aware that just a tiny minority of modern citizens of Western countries go to church?

—I think they are.

—Then how can Europeans get to know the Truth if there are no laborers to reap the plentiful harvest of the vineyard?

—Perhaps some Orthodox hierarchs are of the opinion that it is a task of Catholic priests and Protestant pastors in the West.

—But don’t Orthodox Christians want Europeans to come to knowledge of Truth in Christ and find the path of salvation? Don’t we need to create an Orthodox culture in the West? Can we really achieve good results, relying on our unenviable situation within the Catholic and Protestant space that has been continually declining? I suppose that at the Last Judgment Orthodox hierarch will be asked not only how they took care of their flock, but also whether they looked for “the lost sheep”. Any good shepherd, according to the Gospel, cares not only for the ninety-nine sheep that are safe in the fold, but also for the one that went astray. Unfortunately, I still don’t see that this lost sheep is being looked for.

I understand that the Russian, Romanian, Bulgarian and other Churches are committed to the care for their flock—Russians, Romanians, Bulgarians etc. It is their duty and obligation—nobody denies it. But apart from this obligation they should have a longing for a missionary work among the native people—among whom Russian, Romanian and Bulgarian emigrants live. True, Britain has parishes where services are celebrated almost exclusively in Church Slavonic or Romanian, while there are also parishes with large numbers of British converts where services are celebrated mainly in English. However, these two tendencies exist in two parallel worlds, as it were. We desperately need cooperation, a kind of golden mean. I would like to point out once again that we should get rid of this “diaspora mentality”, of the idea that Orthodox parishes in the West are just a continuation of the Mother Church. I dare say it leads to the heresy of ethno-phyletism.

Liturgical languages are not the only problem, though. There is another difficulty: clergy of various Orthodox jurisdictions are not always inclined to contact and cooperate.

I suppose that in each big city with several Orthodox communities, clergy should gather regularly in order to pray together, discuss life in the Church and share their meal. Then the laity will surely join them too. We should move towards the “open Orthodoxy”. The annual Pan-Orthodox Vespers on the First Sunday of Great Lent is fine, I don’t dispute that; but what about all other fifty-one Sundays of the year? It is important that the Orthodox Church act as one and avoid the separation into ethnic groups. If we want the cooperation at a local level to become a reality, we need special directives from ruling bishops that are in charge of various jurisdictions in the British Isles. The Pan-Orthodox Episcopal Assembly of Great Britain and Ireland is of no use without any cooperation “at the grassroots level”. This kind of cooperation is of vital importance.

Orthodoxy and the British state

As is known, some laws in the UK are in conflict with Christian ethics and morals: for example, the legalization of the so-called “same-sex marriages” so that homosexual couples could have the same rights as traditional families. This has caused discomfort of the Christian communities that strive to firmly uphold the values based on the Bible; these are often under pressure of the authorities (for instance, Catholic adoption agencies in the UK were told not to refuse to help gay couples adopt children!).

—Fr. Gregory, do Orthodox parishes feel pressure from central or local authorities?

—There is no pressure. But it is essential to understand that we, Orthodox Christians, play no role in the life of the British society. We are like an exotic flower in a garden—it is admired and looked after, and nothing more. We are not troubling our Government because we have no influence and are reluctant to take part in anything. Though some changes did take place not long ago, when the House of Lords debated the Assisted Suicide Bill.

—Was the voice of Orthodox Christians heard by the powers that be?

—The situation was the following: the Parliament queried Christians of Britain about their opinion on this bill, but the letters were sent out only to the C of E and the Roman Catholic Church. Then Orthodox Christians sent a letter to the office of the Archbishop of Canterbury inquiring why nobody had asked the Orthodox to voice their opinion—after all, we are the second largest Christian communion in the world numbering 300,000 in the UK alone. In the letter of response we were told that our communities consisted of emigrants who did not even have the right to vote. After that Archbishop Gregorios of Thyateira and Great Britain (the Ecumenical Patriarchate) sent them an excellent letter in return stating that Orthodox Christians have lived in Britain for hundreds of years, that as many as around ninety-five per cent of our parishioners have a right to vote and so forth. Yes, we did receive official apologies from the office of the Archbishop of Canterbury. But did it change anything?

—I have often heard that in general Anglicans are warm and friendly towards the Orthodox.

—We are exotic for them. Beautiful services and icons, beautiful theological reasoning… From an Anglican point of view we are “interesting and valuable” because we are… “Catholics”, but not Roman Catholics! The only reason why they love us is that we give them some “status”, some sense of self-esteem before the Roman Catholics. At one time Anglicans hoped that the Orthodox Church would recognize their ordinations as valid along with their apostolic succession, but this never happened. Meanwhile, the C of E gives way to the Government’s pressure in respect of morality by accepting the things that previously were unacceptable. I think it will eventually approve “same-sex marriages”.

—Yielding to the pressure of the Government?

—The widely known speculations in the press that “the Government will impose same-sex unions on the Church” are senseless. In this case it would have to impose sodomy on Catholic priests and Muslim imams. But it will not happen. I deliberately don’t mention the Orthodox and not because I think that our priests’ standpoint on family relationships is different from that of our Catholic counterparts (our opinions nearly always coincide) but because nobody is interested in our stances. So why should the Government take the trouble to ask the Orthodox about anything and impose anything on us?

Saying good-bye to Fr. Gregory, I thought that the problem of the reapers and the vineyard is becoming ever more relevant for the UK, while secular trends and even anti-Christian tendencies are growing. By the way, the new ruling hierarch of the Diocese of Sourozh (a diocese of the Moscow Patriarchate covering the territory of the UK and the Irish Republic), Bishop Matthew (Andreev), at one time headed the Diocesan Missionary Department and resided in Manchester, though the objects of the mission were mainly emigrants from traditionally Orthodox countries. True, there are quite a few emigrants in the UK and their spiritual needs should necessarily be met. But, at the same time, as Fr. Gregory rightly said, we shouldn’t forget “the lost sheep”: after all, any good shepherd is ready to (temporarily) leave the remaining ninety-nine sheep in his flock to find and rescue the one that went astray. “I say unto you, that likewise joy shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, which need no repentance” (Lk. 15:7). However, without an active mission in the British Isles their native inhabitants will hardly be able to repent and return to Christ.

Christ is the head of the Orthodox Church. Period.

When we stand before His judgement seat,He will not be asking us to engage in a debate or conference.

This book could be a great missionary tool for yound English people. Please translate it if you have money for good translator (who knows old language).