Unfortunately, we’ve seen in history that the virus of envy also effected Christians powers, including the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. It is worthy to mention that of the 66 Byzantine Emperors, 33 were cast down from the throne1, and this was primarily due to ambition and envy.

We will touch only on a few key moments of the History of Byzantium relating to its catastrophes, and in the final analysis, it’s fall.

Byzantium

First Period 601-602 A.D.

The Imperial Army was waging a successful war against the Slavs on the Danube, crossing by way of that river and causing terrible devastation in Slavic villages. The Army, however, grew tired of the constant winter expeditions, and began to grumble.

This was used by the ambitious, demagogue centurion Phocas, who stirred up rebellious moods, and rose the army to revolt, leading them on Constantinople. Envious gentry in Constantinople were plotting against Emperor Maurice and thereby paralyzing all resistance of the rebellious army at the Danube.

Phocas entered into Constantinople, executed the Emperor and his sons, and then instigated a real terror, including even against those who contributed to his ascension to the throne. In general, all this somewhat resembles our two revolutions in 1917, and in particular, the shooting of the tsar’s family in 1918.

Byzantium at the beginning of the seventh century even had it’s own [foreign.—Trans.] intervention. The Persian King Khosrow [the second.—Trans.], taking advantage of the death of Emperor Maurice, his benefactor, declared war on the Roman Empire, and won a series of striking victories, ceasing Armenia and Syria2 [which was not a foreign, but heartland territory of the Roman Empire.—Trans.]

For twenty-seven years the Byzantine Empire lead an exhausting war against Persia, having won by a miracle, and exhausting its final resources. As a result, when the weakened Eastern Roman Empire was attacked by Arabs under the leadership of Mohammad, it no longer had the strength nor the will to resist.

In what followed, Muslim fighters occupied Syria, Palestine, Armenia, Egypt, North Africa, and threatened Constantinople itself. In other words, if Islam [its emergence.—Trans.] was partially the fruit of Christian heresies, in particular Nestorianism and Gnosticism, then its successes [and spread.—Trans.] was the fruit of envy among Christians.

Second Period – 1071 A.D.

Among the Byzantines was every chance at victory; but in the army there was a hotbed of treason.

The warrior-Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes moved his troops to Armenia against the Seljuk Turks, nomads who had emerged from Central Asia. The army was great in numbers and well equipped, Romanos was an excellent commander. Among the Byzantines was every chance at victory; but in the army there was a hotbed of treason. The noble family of Doukas envied Romanos, and sought to overthrow him; repeatedly assassination attempts on the Emperor were organized. In the Battle of Manzikert, when the victory of Romanos was close, one of the Doukas clan shouted that the Emperor was dead, and that they [The Romans] needed to retreat.

This lying fake news led to panic, and the flight of the Byzantines. The battle was lost, and the Emperor [who was really alive.—Trans.] was captured, after which a free road to Asia Minor opened for the Turks. Then a civil war broke out between the Doukas family and Romanos [who was freed by paying a massive ransom3—Trans.] As a result, Emperor Romanos was again captured and wickedly blinded.

Meanwhile, the Turks seized the rich provinces of Asia Minor which was a base of Byzantine might, and a fortress of their army. As a result, ten years after Manzikert, the Turks made it to the Aegean Sea. The new Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, with the help of the crusaders, was only able to win back half of Asia Minor, while the rest was lost forever for the Empire, which began to decrease to its end. This is the price of the envy and betrayal of the Doukas.

Third Period – 1195

The campaign did not end with victory because of the treason of the envious brother of the Emperor…

Emperor Isaac II Angelos, having overthrown the cruel usurper Andronikos I Komnenos, was able to restore relative order in the country, and expel the invading Normans from Thessaloniki. In 1195, he was on the eve of defeating the rebellious Bulgarians. The campaign did not end with victory because of the treason of the envious brother of the Emperor – Alexios Angelos, who solicited the throne.

Alexios plotted against his brother Isaac, insidiously captured and blinded him, and became Emperor. The consequences of his accession to the throne were disastrous.

First of all, the war with the Bulgarians, at the head of which was the formidable John Kaloyan, had been lost, and they signed a peace treaty which was shameful for the Empire.

Secondly, corruption and lawlessness prevailed in the country: it reached the point where the head of the prison of Constantinople “Lagos” released thieves at night to “go fishing” [i.e. to steal.—Trans.] and share with him what they “caught”, and the Droungarios (admiral) of the Imperial Fleet Striphis, nicknamed “Fat-belly” sold all the property entrusted to him, from warships to ropes and nails.

Thirdly, Alexios, son of Isaac Angelos managed to escape from the dungeon and made his way to the West, where he persuaded the western lords to restore to the Byzantine Throne his father—the blinded Isaac—promising to pay a large sum of money. They were very attentive to such invitations in the West, and the participants of the Forth Crusade set out for Constantinople instead of Egypt.

The rest is well known history: The crusaders overthrew Alexios III Angelos, and elevated Isaac, who was unable to pay the monstrous ransom, and was deposed by the intemperate Constantinopolitans, and then, on April 11, 1204, the crusaders took Constantinople4 and subjected it to terrible robbery and ruin, and after which it occupied around half of the Byzantine Empire.

The Eastern Roman Empire was dealt a terrible blow, from which it was never able to recover. Here are the consequences of but one coup, caused by adverse circumstances. It clearly imposed upon the general spiritual and moral status of the subjects of the Roman Empire, a state which in the words of historian Niketas Choniates5 was described as “a head sick with a raging drunkenness”. As with any catastrophe however, there is always a decisive impetus and event, which in this case, was the coup of Alexios III Angelos, caused by envy and ambition.

Period Four – the start of the civil war 1342-1349

The Byzantine Empire ceased to exist as a great power

This war finally undermined the Byzantine Empire, and set the stage for its conquest by the Turks [ending in 1453.—Trans.], as well as their occupation of the entire Balkan Peninsula and adjacent lands6. The war began due to the envy of the timeserver7 Alexios Apokaukos of the prominent commander and theologian John VI Kantakouzenos, who was accused of treason, even though Kantakouzenos was loyal to the young Emperor John V Palaiologos.

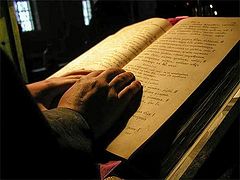

Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354), Apokaukos's patron and victim of his protégé's ambition. Photo: wikipedia.org

Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354), Apokaukos's patron and victim of his protégé's ambition. Photo: wikipedia.org John was made out to be a traitor to the state, and forced to flee to the Serbian King Stefan Dušan, who used this situation to conquer Byzantine lands. As a result, by 1349, the Serbs had seized five sixths of Byzantine lands. The Byzantine Empire ceased to exist as a great power.

After the death of Stefan Dušan, the Turks seized the remaining Byzantine rulings in Thrace, Bulgaria, and Serbia; and they succeeded, particularly because during the time of the civil war, Turkish mercenaries in the service of John Kantakouzenos studied [and scouted] the Balkans extensively.

John Palaiologos became a vassal of the Sultan, and was forced to go with him on campaigns against Christian cities, including his own domain.

In 1389, Serbia was defeated [at the Battle of Kosovo Fields.—Trans.]8, and Bulgaria was occupied by the Turks.

And then on all sides Muslim territories surrounded Constantinople, which fell in 1453 after bitter final resistance.

It is clear that the final reason for the fall of the Byzantine Empire was the adoption of the Florentine Union of 1439, but it was precipitated by previous events including the civil war of 1342-1349.

Rus’

Was it not envy that lead to defeat as described in “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign”?

Are catastrophic events connected with envy characteristic only of Byzantium? Alas, no. If we read Russian history, we will see that this vice was quite clearly manifested in our history. Did not the murder of Saints Boris and Gleb resemble Cain’s fratricide; was it not the result of envy?

The continuing fierce struggle between the descendants of Equal-to-the-Apostles Saint Vladimir, in particular among the Yaroslavichi [sons of Yaroslav the Wise], was largely due to envy, more precisely, to the desire to receive the Kievan “Golden Table” – i.e. the Kievan Principality – and thereby seniority among the Russian Princes.

It is very much this phenomenon which was described in “A Tale of Igor’s Campaign9”

For brother sayeth unto his brother,

“This is mine, and this mine be also!”also is mine!”

And of trifles and small matters Princes began to say, “This is Grand”

Brother against another discord they designed,

all while pagans advanced with victories against the Russian land.10

And was it not envy that lead to the defeat described in “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign”? The Grand Prince of Kiev Svyatoslav, in 1184 dealt a heavy defeat to the Polovtsians11 [Cumans.—Trans.], and took rich spoils from them.

The Prince of Novgorod-Seversky12 Igor Svyatoslavich, and his brother Vsevolod, did not participate in the battle. Envious of the success of Svyatoslav, they decided in the spring of 1185 to go on campaign, to become rich and famous. Here is how their boasting is reflected in The Tale:

We will seize our coming glory for ourselves,

and divide the glory of yore among ourselves!

Even as the Polovtsians were enemies of Rus’, and worked much evil, the author of “The Tale” strongly condemns this motivation:

[Dishonorably you were vanquished.—Trans.] …for dishonorably you wished to shed pagan blood!

And it is understandable why. The killing of even enemies, without being justified by the defense of native land, is not acceptable to God13. Igor’s campaign ended with the shameful routing and destruction of his entire host.

From the point of view of the author of “The Tale”, this was totally natural, because the cause of the campaign was envy, love of glory, and greed, and therefore the blessing of God could not be on him.

If we consider the events that precipitated the Mongol Conquest [of Rus’.—Trans.], we see how great of a role the Russian princes’ envy, pride, and love of power played.

We will give only some examples:

In the first campaign against the Mongols in 1223, almost all the Southern Russian Princes went to Kalka River, but each went into battle with his retinue separately. There was no general [common, unified,—Trans.] command over the troops.

Moreover, when Mstislav Mstislavich the Bold learned of the Mongols approach, he did not inform the other princes, as the chronicler adds, “for envy’s sake”.

And Mstislav Romanovich the Old is in general special, because he did not participate in the battle at first, not wanting to help Mstislav the Bold.

The result of the Battle of Kalka ended in a terrible rout; nearly all the Russian army was destroyed, two dozen princes lead by Mstislav Romanovich were taken prisoner and crushed alive by the Tatars during their feast.

And this catastrophe did not enlighten the Russian Princes, rather, princely feuds continued up until the Mongol Invasion—and even at that time.

Shortly before Batu Khan’s campaign for Kiev, he selected first Mikhail of Chernigov from Yaroslav, and then Daniel of Galicia from Mikhail. After Batu’s pogrom against Kiev, “The Mother of Russian Cities”, there was no one left to select.

The Mongol-Tatar yoke would not have been so long, had it not been for the discord of the Russian Princes

Perhaps the Mongol-Tatar yoke would not have been so long and hard, had it not been for the envy and discord of the Russian Princes.

It is worth recalling the quarrel between the sons of Prince Saint Alexander Nevsky—Dmitry and Andrei. Andrei Alexandrovich, envying his brother, Grand Duke Dmitri, raised the Tatars against him, and with their help ruined Northern Russia worse than Batu Khan had done. And how accurately noted A.K. Tolstoy:

Then many bad things fell upon Rus’.

A day when brother was against brother

In the horde spoke slander and defamation,

The land was once rich,

Now there is no order

Only the iron hand of the Grand Princes of Moscow were able to unite Rus’, and to put a stop to the terrible evil of discord, that arose from princely envy. However, in the Muscovite Period, envy also exerted a bad influence on the life of the country.

It is worth recalling the vice of Mestnichestvo14 [a special feudal hierarchy,—Trans.], which was a vainglorious determination of who is above whom, in the court of the Grand Prince, and later, the Tsar.

Because of Mestnichestvo, a series of battles were lost during the Muscovite period. This was because the Voivodes, instead of meeting the enemy in battle and saving Russian cities and villages from them, often “fought over places15” for several days16.

The Time of Troubles also partly arose from Boyar envy in relation to Tsar Boris Gudunov—an arrogant upstart from the point of view of the ancient boyars, the Rurikids and the Gediminids. How accurately noted V.O. Klyuchevsky:

“The imposter17 was only baked in Lithuania, but he was mixed Moscow.”

Indeed, as soon as Tsar Boris learned of False Dmitry, he was told to his face by the boyars that it was their handywork. The treason of the Boyars opened the way to Moscow for the Imposter and the Poles, and having arranged an insurrection in the capital, ensured the success of his plans.

He however also fell victim to the Boyars envy and uprising against him and the Poles. The intriguer and envious Vasily Shuisky could not resist the atmosphere of self-will, love of power, and envy created by himself in part, and he was also cast down as the result of conspiracy and treason.

The Palace Coups of the eighteenth century are also partly a consequence of ambition and envy.

Envy in the imperial period at times it was also the cause of defeat: So it was with the Samsonov Catastrophe [the Second Battle of Grunwald/Tannenburg18—Trans.], the death of the Second Army in eastern Prussia in August of 1914.

It was due to the fact that the commander of the First Army, General Paul Edler von Rennenkampff didn’t give aid to the commander of the Second Army, General Alexander Samsonov because of envy; according to other sources, this was revenge, saying Samsonov didn’t help Rennenkampff in his time of need during the Russo-Japanese War.

The emergence of Russian capitalism and competition is also connected with this sin, with “a beastly appetite, unheard of,” in the words of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky.

And of course, it is impossible to imagine the Russian Revolution without this vice. If we take a close examination of the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia, we will see that before the beginning of the twentieth century, it was from the nobility in large part.

The Decembrist Revolt was of nobles and officers. The soldiers were dragged into it by deception and went into Senate Square, “for Emperor Constantine and his wife…for the constitution.” And what was the reasons of Decembrist speech? At the first, superficial view—the good of the people19 and the emancipation of the peasants. And if you dig deeper?

In no small part, the Decembrist revolt is connected with the struggle within the nobility and the wild envy of less fortunate families and individual nobles to the more successful ones, those who, according to Lermontov were “the greedy mass around the throne”.

Many of the Decembrists understood that there were no places close to the throne, so the problem must be solved severely—crush the throne, destroy the Imperial Family, and gain the fullness of power, “So that the republic will be King,” in the words of Pestel. And at the same time, to continue to “milk” [exploit.—Trans.] the peasants.

Ivan Solonevich was profoundly correct, when he spoke of the centuries old struggle of the nobility, “of the wild gentry”, with the Autocracy, and also how Nicholas I was saved by a Russian commoner in guards uniform.

The same could be said in many respects to the reign of Alexander II.

Who shot him in 1866? The noblemen Dmitry Karakozov. Who saved the Emperor? The Russian commoner Osip Komissarov, who knocked the pistol out of the terrorist’s hand.

When the Raznochintsy20 organized a march for the people, the Russian commoners turned their hands on them and dragged them to the police station as soon as they realized the gentry were bringing them to a rally against the Tsar. And finally, who helped kill Alexander II? The governor’s daughter, Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya.

In seven months, the timeservers destroyed a power that was built over centuries.

The fact that this aspiration caused the February Revolution is obvious: before February 1917, conspiracies against the Emperor were being discussed. One of them implied the deposition of the Passion bearer Emperor Nicholas II, the imprisonment of the Empress Saint Alexandra in a monastery, and the enthronement of the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaievich—an ungifted commander who considered himself a military genius.

The February catastrophe arose from the obvious desire of the so-called elite to steer the country, in place of whom they regarded as “the narrow sovereign”. In seven months, timeservers from the interim government destroyed a great state which took centuries to build, and the Bolsheviks did not even have to seize power—it was lying on the ground.

The consequences were clear: The shameful Peace of Brest, the Civil War, terror, famine, typhoid, Spanish flu, between 15-20 million dead and killed, the loss of Poland, Finland, the Baltic, Western Ukraine and Belarus, and Moldova. This is the price of the envy of the nobles and the Raznochintsy for Autocracy and the Autocrat of All-Rus’.